When Marian Anderson took the stage at New York’s Metropolitan Opera on this day in 1955, TIME wrote, “there were more Negroes in the audience than anyone had ever seen at the Met.” The reason was clear:

In Box No. 35 of the Golden Horseshoe, the place usually reserved for visiting statesmen and royalty, sat a small, aged lady who had once been a washerwoman in Philadelphia. Her name was Anna Anderson. As a girl, her daughter dreamed of singing in this great gilt and plush house. Now, at 52, Contralto Marian Anderson was realizing the dream. The first Negro singer to appear at the Metropolitan, she was making her debut in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera.

There’s a lot to cringe at in TIME’s coverage of Anderson in the middle of the 20th century—not only the use of that then-common, now-defunct term “Negro,” but also her characterization as “dusky” and a perhaps well-meaning but tone-deaf statement that her achievement, “as with every Negro … is inseparable from the general achievement of her people.” That’s a lot of weight to hang on any person’s shoulders.

Yet the lily-white media was not wrong that her accomplishments carried great significance. Even before her landmark performance as the first black person to sing at the Met, she had earned herself a prominent place in the civil rights movement after a brush with the Daughters of the American Revolution. When her manager tried to book a concert at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. in 1939, the D.A.R. (the group that still owns and operates the venue) said there was no availability. As TIME reported, “while the Daughters continued to preserve a thin-lipped silence, Daughter Eleanor Roosevelt announced in her syndicated Scripps-Howard column that she was resigning from the D.A.R. in protest.”

As a counter-move, Anderson instead gave a concert at the base of the Lincoln Memorial, waiving her fee of $1,750 and performing for an audience of 75,000. The photo of the singer with Lincoln looming over her shoulder became iconic.

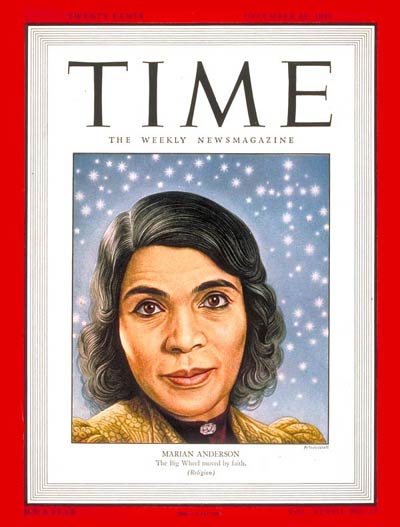

Anderson was primarily known for concerts and recitals like these—performing at the opera was an anomaly in her career—and, while she got her start in Europe perfecting German lieder by Brahms and Schubert, she would later be celebrated for her classically-inflected African American spirituals like “Crucifixion” and “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” She performed at the inaugurations of two presidents, Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy, and was one of only a few black singers to perform at the March on Washington. (The organizers featured white singers like Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, a decision for which they were criticized.) When TIME put her on the cover in 1946, the story went in the “religion” section, not “music,” and Anderson was hailed as “the religious voice of a whole religious people—probably the most God-obsessed (and man-despised) people since the ancient Hebrews.”

Among any oppressed peoples, there will be any number of firsts whom journalists and historians will assign monumental importance—and doing so makes sense in the case of Anderson, who opened the door for countless other black singers, from Robert McFerrin, Sr. (who debuted at the Met only a few weeks after Anderson, and whose contract-signing actually preceded hers) to Lawrence Brownlee, who starred in last year’s performance of I Puritani. But that view, which sees pioneers only as icons and not also as individuals, can be narrow-minded in its own way: often, white performers are celebrated for the ways they differ from everyone else, while black performers are proclaimed to be stand-ins for their entire race.

Anderson, fittingly, had a habit of rhetorically erasing her own significance by referring to herself as “one” — and she didn’t behave like the typical prima donna in her debut at the Met:

“I’m not quite sure it’s happening,” Contralto Anderson told friends and reporters [after the performance]. Apologizing for her jitters, she added: “A serious person, when beginning anything, is usually a little overanxious.” … As for the possibility of other roles at the Met, she said in her modest, impersonal way: “One is so involved in this one, no other has been thought about.”

Meanwhile, out in the packed house, it was the crowd that lifted the singer to hero status: “There were eight curtain calls. ‘Anderson! Anderson!’ chanted the standees,” TIME reported, “and men and women in the audience wept.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com