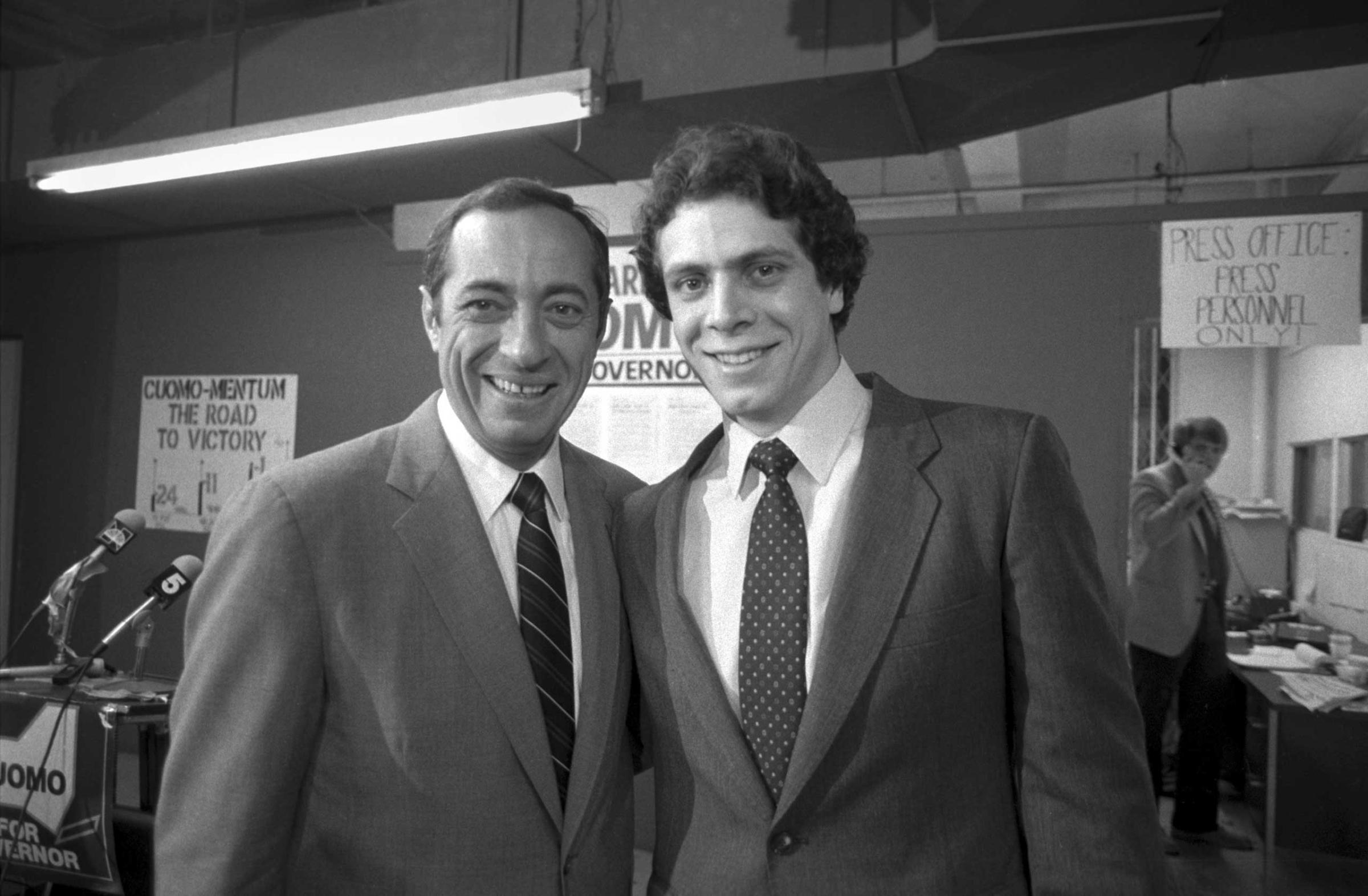

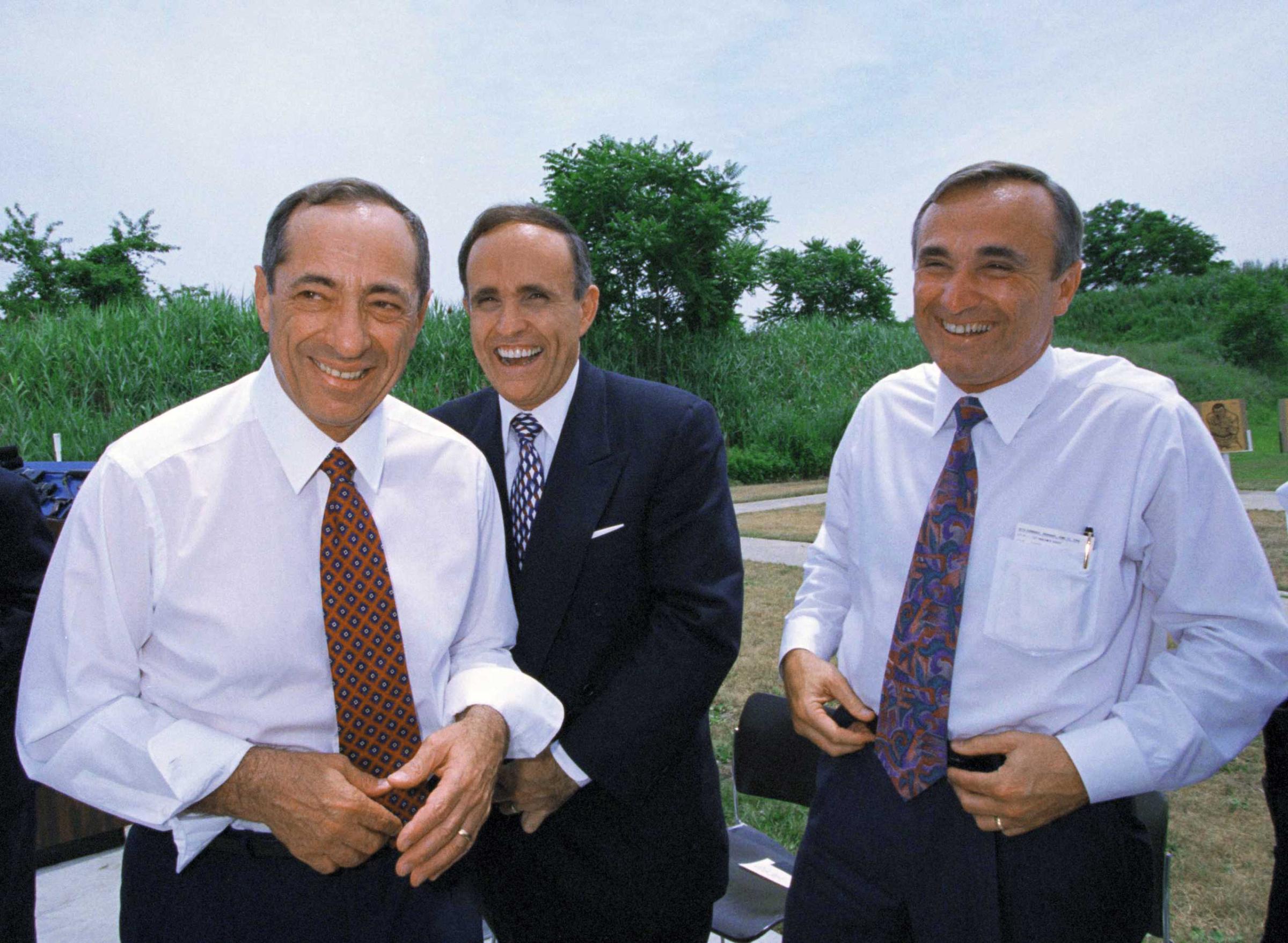

Andrew Cuomo once told me that I had “sort of a father and son relationship” with his father, Mario, who died Thursday at the age of 82. I’m not sure what he meant by that. Cuomo and I argued a lot, at length–but it was sportive arguing, a kind of dance. We once watched at entire New York Knicks game together on television—with the governor on the phone in Albany, me on the phone in New York. We spent the first half arguing politics; the second half talking sports. He favored a new rule: a five-point shot from half court or deeper.

Andrew also told me that the difference between him and his father was that Mario—and Andrew always called him Mario—focused on what should be done and Andrew focused on how to do it. Once, on the phone, Mario asked me why I hadn’t given him credit for increasing education funding by—he claimed—90%. I replied, “You did that? Oh, I’m so sorry.”

“Why are you sorry?” He asked, bristling.

“Because the schools still [stink],” I replied. He was, of course, furious. He trusted me enough to get angry at me. He knew our conversations were private; he knew that I valued them too much to ever use them against him.

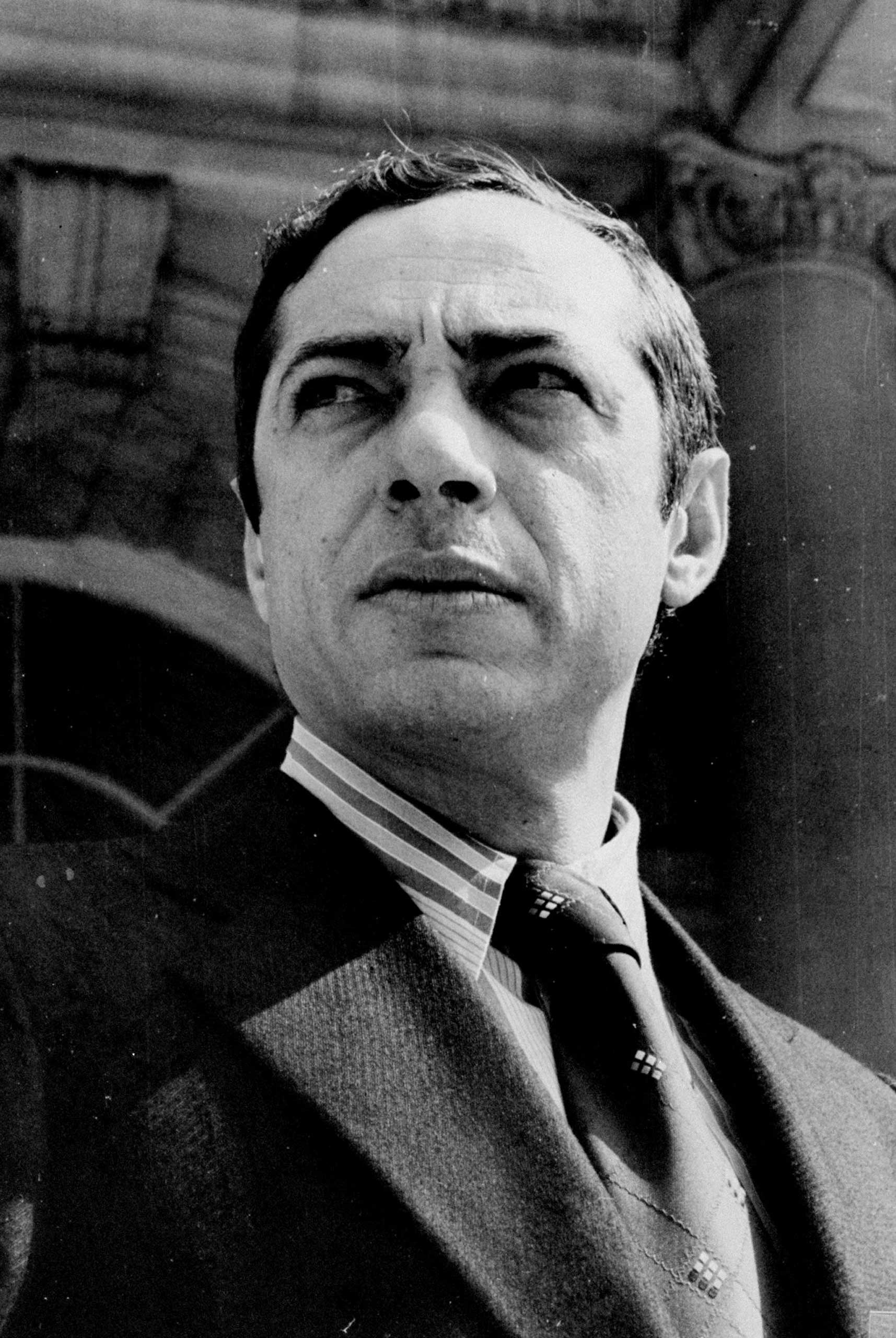

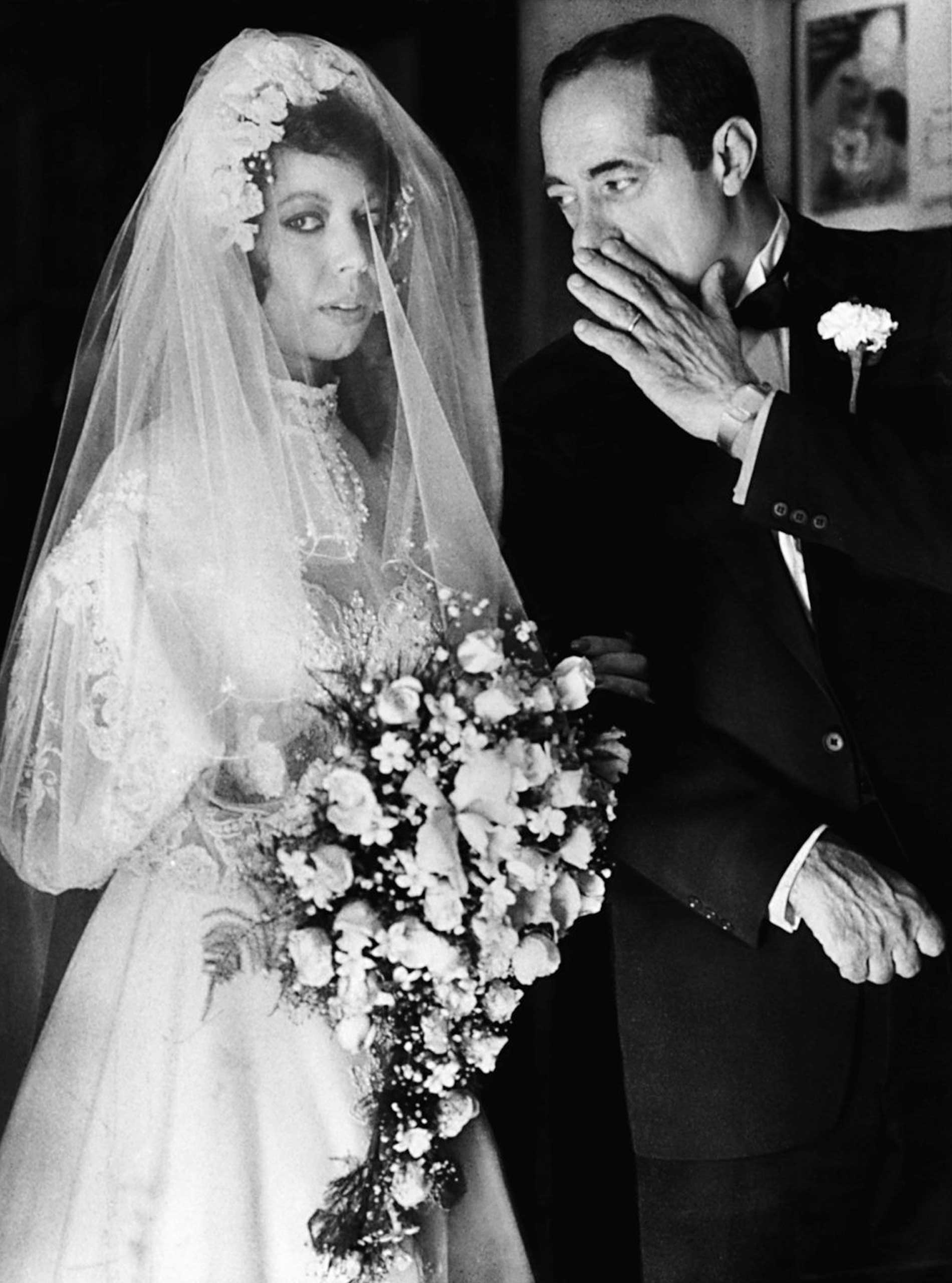

See Mario Cuomo's Life in Pictures

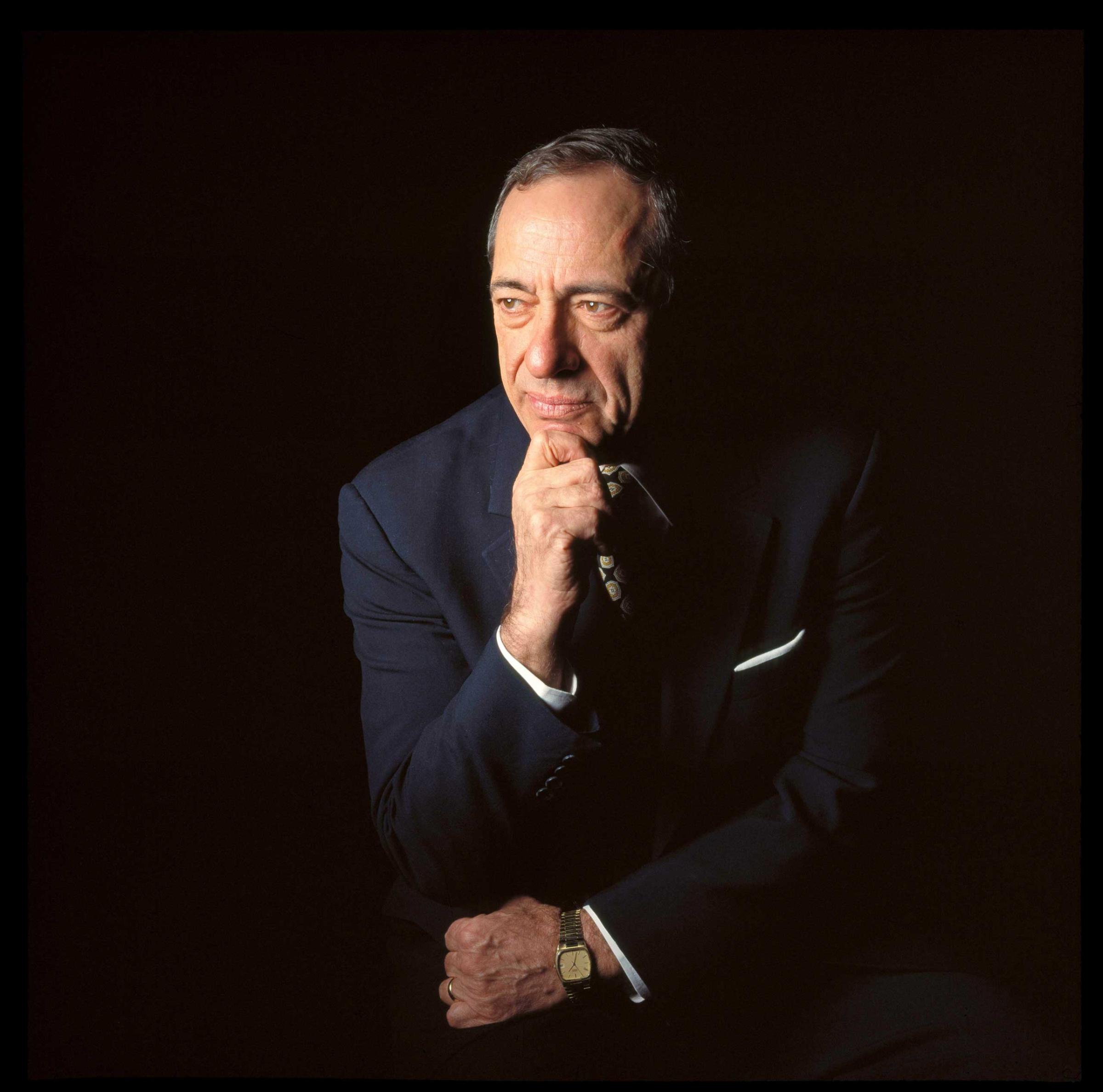

We disagreed about a lot of things, but I loved the fact that when it came to policy his first instinct was compassion. (Politics was another matter. He could be brutal toward his enemies.) One of those enemies once told me that Cuomo was “a Queens ward-heeler with the voice of Abraham Lincoln.” But that was unfair; Cuomo’s rhetorical brilliance was rooted in personal experience. His heart was always—always—with the workers “whose fingers are too thick to work a computer keyboard.” He was, indeed, old school outer-borough New York, my New York. He once asked me if I wanted to go to Japan with him on a trade mission and I said no. “Why not?” He asked, shocked. I told him that I knew exactly what he would do when he got there. He would go to his hotel room and spend six hours on the phone back to New York, go to a couple of trade meetings with Japanese officials, have a ceremonial dinner where he’d feel uncomfortable, get back on the plane and go home. “When I go to Japan,” I said. “I want to go to Japan.” He agreed that I had a point. I asked him why he was like that. “I grew up over the store,” he said. “I get nervous when I’m not close to the store.”

Which was why, I think, he never ran for President. He was afraid he’d get to Iowa and do something New York stupid, like mistake corn for wheat. He also, I suspect, felt that way about the Supreme Court, a position he was offered by Bill Clinton: he would have to compete with another smart Italian, Antonin Scalia, and might not be up to the job. He didn’t understand that his big heart, his basic instincts, his athletic cleverness, was exactly the moral challenge that Scalia needed.

Father and son? Well, we did have conversations of a personal quality that I’ve never had with a politician before or since. Just after Michael Dukakis lost the presidential campaign of 1988, I told Mario what an old Boston politician had once told me, “Dukakis was never like us”—he meant a working-class ethnic sort—”he was never ashamed of his father.”

I said it as a provocation. Cuomo had worked hard for Dukakis. But he didn’t flash back at me. He was silent for a while; I could feel his brain cranking. And then, finally, he said, “I used to hate going to parents’ night in school. My father couldn’t speak English. I was so embarrassed. I would try to keep him away from my friends.” He called me back three days later, having polled his inner circle—Fabian Palomino, Sandy Frucher, others—about whether they’d been ashamed of their fathers. “You sure hit a nerve with that one,” Frucher told me.

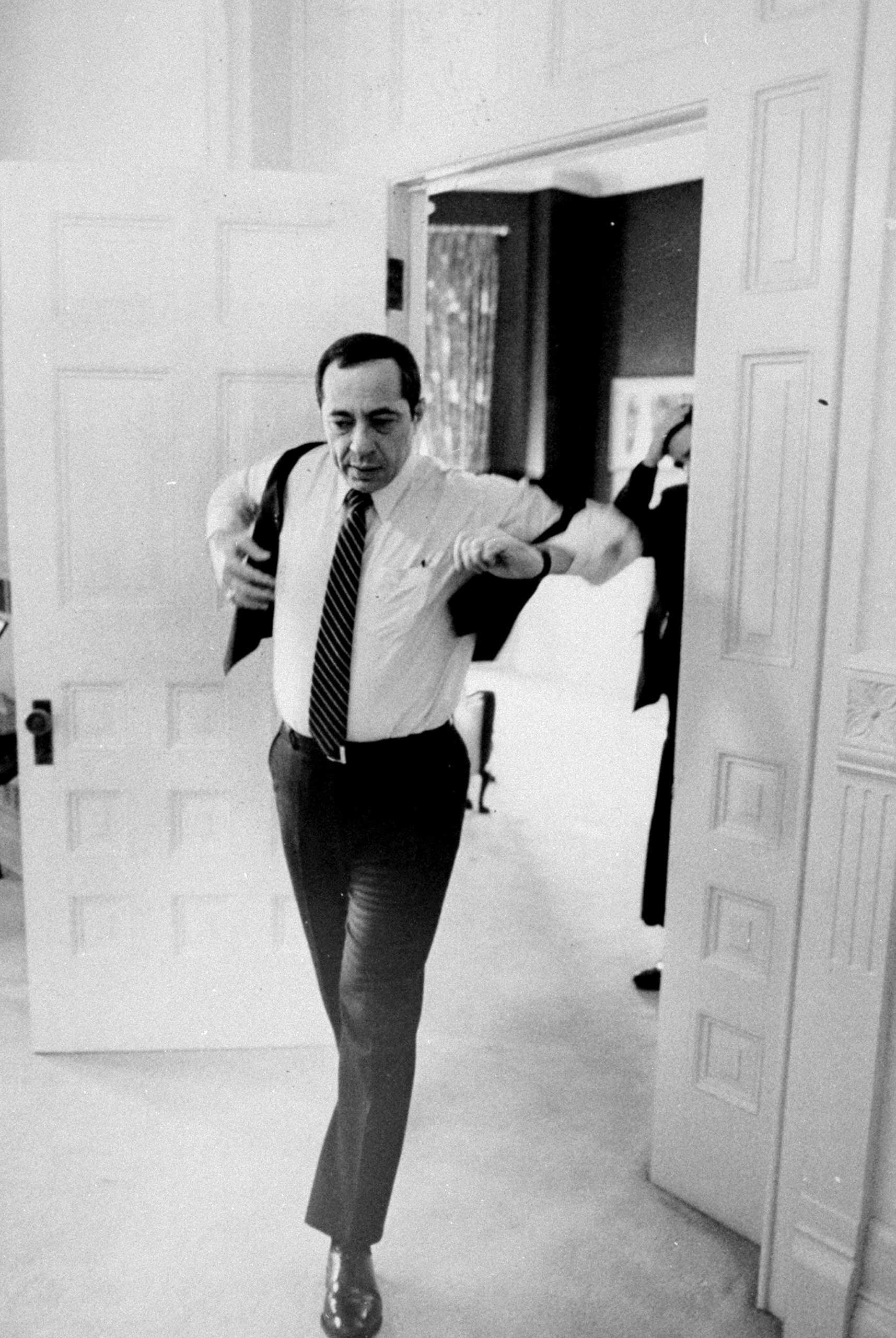

But I remember Mario best on the stump in the 1982 gubernatorial primary, running against Ed Koch—who was, like, 30 or so points ahead at the beginning of the race. Koch was hammering away on the death penalty. The polls said the people were for it, overwhelmingly. Koch was for it. Cuomo was against it.

And Cuomo made it the central issue of his campaign. We went from town to town in upstate New York, just a few of us—all the press and smart money were with Koch at that point. Mario would hold town meetings, knowing viscerally that he could only win their votes if they knew what kind of man he was. And he needed the death penalty for that. If they didn’t ask him about it, he’d ask them, “Doesn’t anyone want to ask me about the death penalty?”

He would tell them whether they wanted to hear it or not. He would tell the story of how one of his daughters was accosted by a thug on the street in Queens who burned her breast with a cigarette. “Did I want to murder that guy? Absolutely. My son Andrew got into the car with a baseball bat, looking for the guy. I would have torn him apart with my bare hands if I’d ever found him … But would have that been the right thing? No. It would have been the barbaric thing to do. That’s what we have government for—to protect us from the barbaric side of human nature.” The state, as an exemplar of moral rectitude, had to abide by the commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.”

People would come up to him after the meetings and say, “I’m still not sure I agree with you on the death penalty, but I certainly respect your position.” In the end, they decided to vote for him. They voted for him because Mario Cuomo was a man to respect, a man who respected them well enough to tell them what they didn’t want to hear.

Read next: Pro-Choice Mario Cuomo Was Still A Catholic Politician

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com