You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

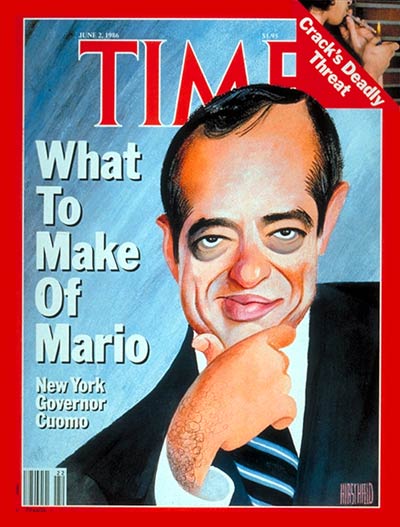

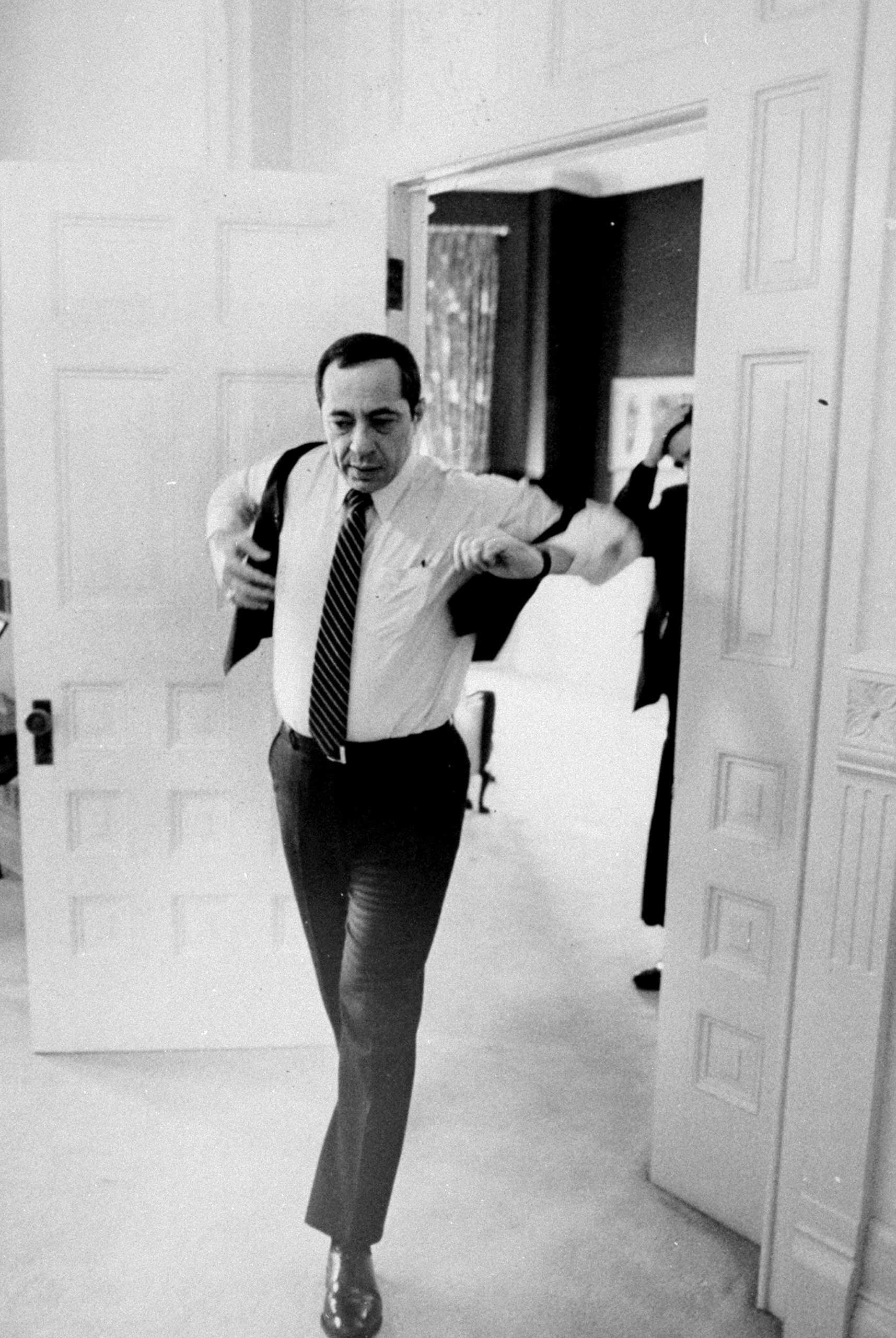

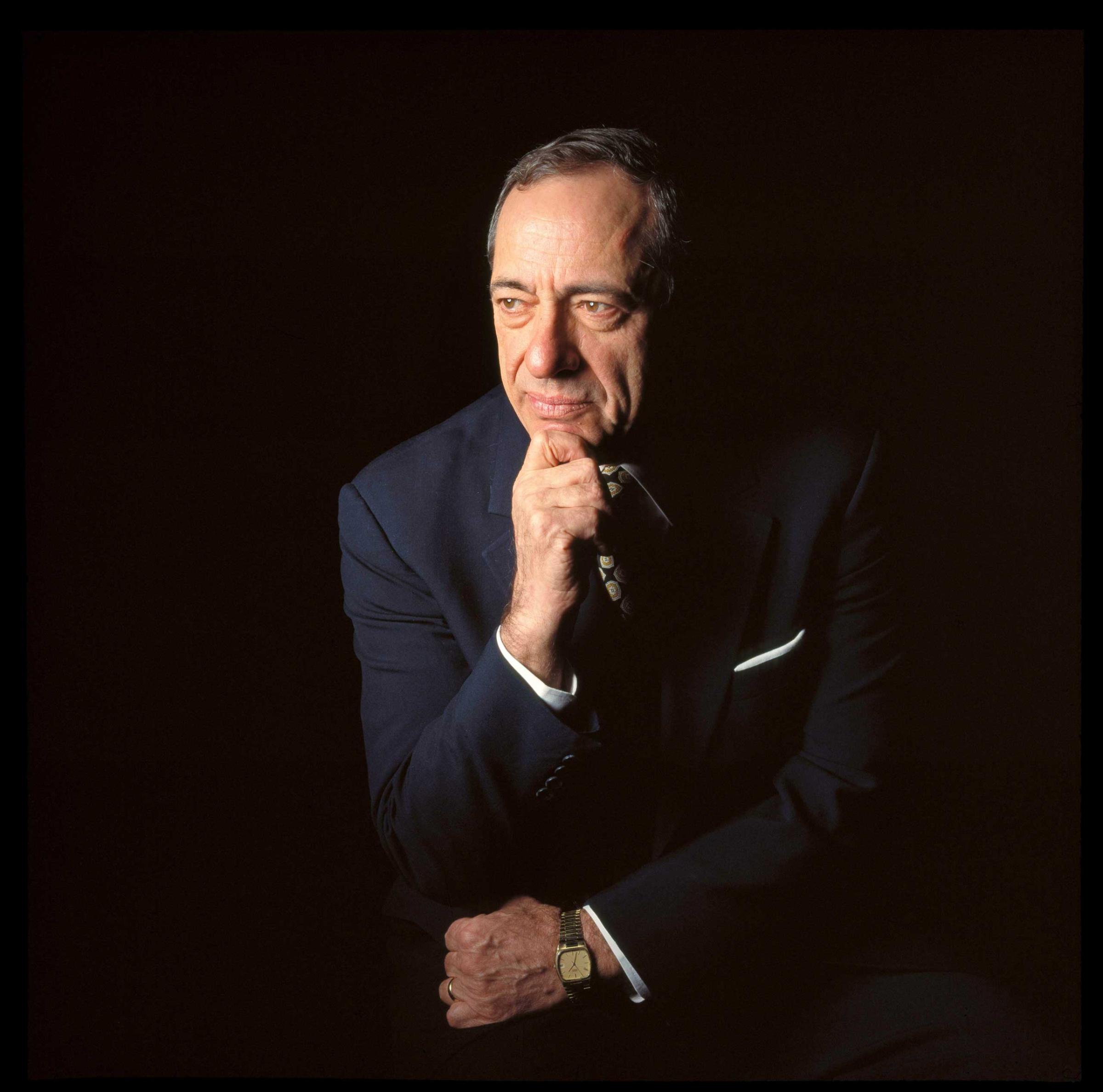

The face, broad and fleshy, with dark-ringed eyes and a gap-toothed smile; the body, stocky and powerful, slightly uncomfortable in the boxy blue suits; and the hands, strong and blunt like small shovels–all combine to give him the look of one of the proud immigrants who toiled in the caissons deep below the East River to build the Brooklyn Bridge. A laborer, a man capable of bearing heavy weights, a man of explosive passions and simple pleasures. Someone strong. Someone you do not want to tangle with.

Then a rustle of papers, and the man puts on a delicate pair of wire-rim glasses. He begins to talk, to speak in smooth, connected sentences. As if by conjurer’s trick, the laborer is transformed into the scholar, a solitary thinker who shies away from the world of action, a man of introspection who rises early to wrestle with questions of motivation and desire and write about them in a thick loose-leaf notebook.

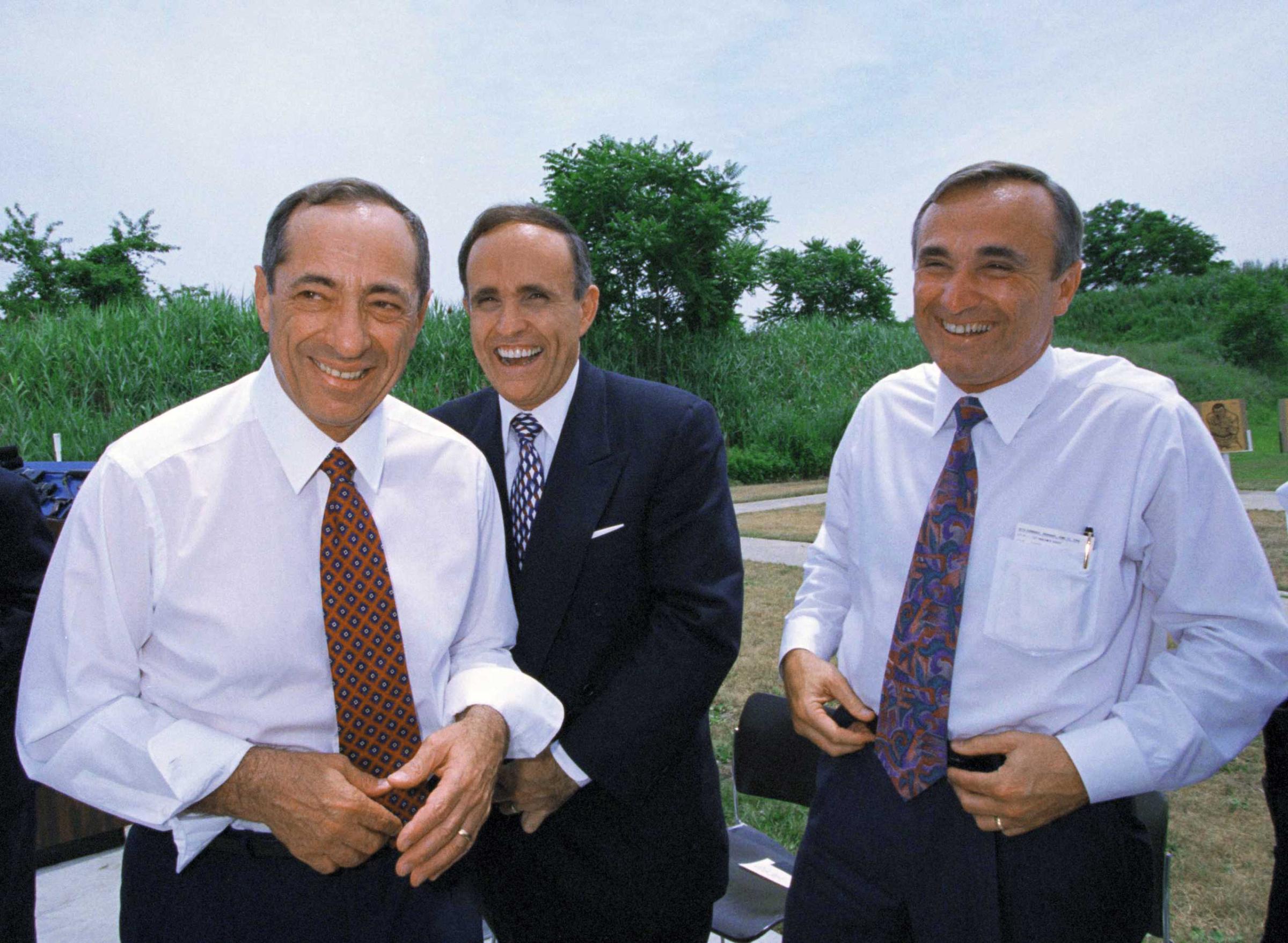

Mario Matthew Cuomo, 53, the Governor of New York, is both of these men, the man of strenuous action and the man of otherworldly contemplation. Like the titans he frequently invokes–Jefferson, Lincoln, Roosevelt–he is a man who battles inwardly between passion and reason, between his ambition and his doubts. Some believe that out of this man’s head and heart may come the soul of a new Democratic Party, and perhaps the strength to lead it to the White House in 1988.

See Mario Cuomo's Life in Pictures

The push and pull between the Governor’s aspiration and his uncertainty was visible last week as he announced at press conferences in Albany and Manhattan that he would run for re-election this year. Despite his long insistence that it would be self-defeating to run for Governor in 1986 and then turn around and run for President, he did not rule out a try for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988. Standing behind a lectern in a high- ceilinged, wood-paneled room near his office at the state capitol, a composed and confident Cuomo said, “I have decided to run for Governor. I have no plans to run for the presidency.” When reporters pressed him about 1988, Cuomo tap-danced around their questions. Why did he not end all the speculation and say he would not run for President? asked one reporter. “I don’t want to lock the door against eventualities that I don’t even understand or imagine,” replied Cuomo, as if instructing a class of stubborn undergraduates. “I’m not God. If you have a crystal ball, if you can tell me what’s going to happen, fine. But I can’t.” Asked directly whether he would pledge to serve a full four years as he promised last time, Cuomo was uncharacteristically brief. “No,” he replied.

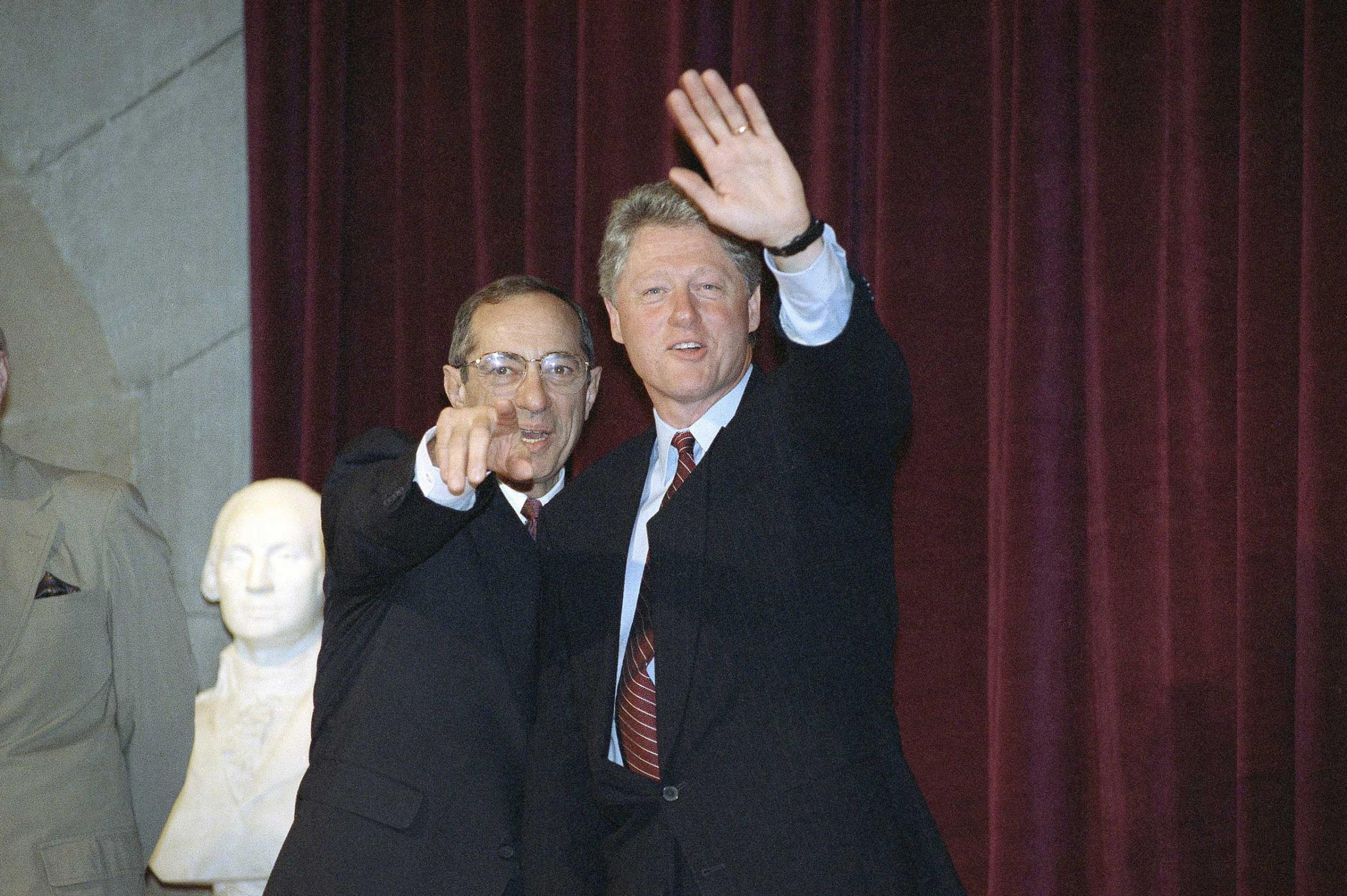

Political observers suggest that an impressive re-election might provide Cuomo with his best possible presidential launching pad. Victory in November is considered a sure thing. His approval rating in New York hovers around 70%, and he has already raised a campaign war chest of some $10 million. His probable opponent, Westchester County Executive Andrew O’Rourke, is a relative unknown.

Some Democratic officials regard Cuomo’s announcement as part of a strategy of running for President by not running. Party leaders in key states see Cuomo’s move as a practical one. Says New Hampshire State Democratic Chairman George Bruno: “It was the smart and logical thing to do.” Cuomo is the Democrats’ most influential and visible state executive, and it would make no sense for him to abandon his forum. Notes Alvin From, executive director of the Democratic Leadership Council: “The best strategy for a Governor in his position is to get safely re-elected this year.”

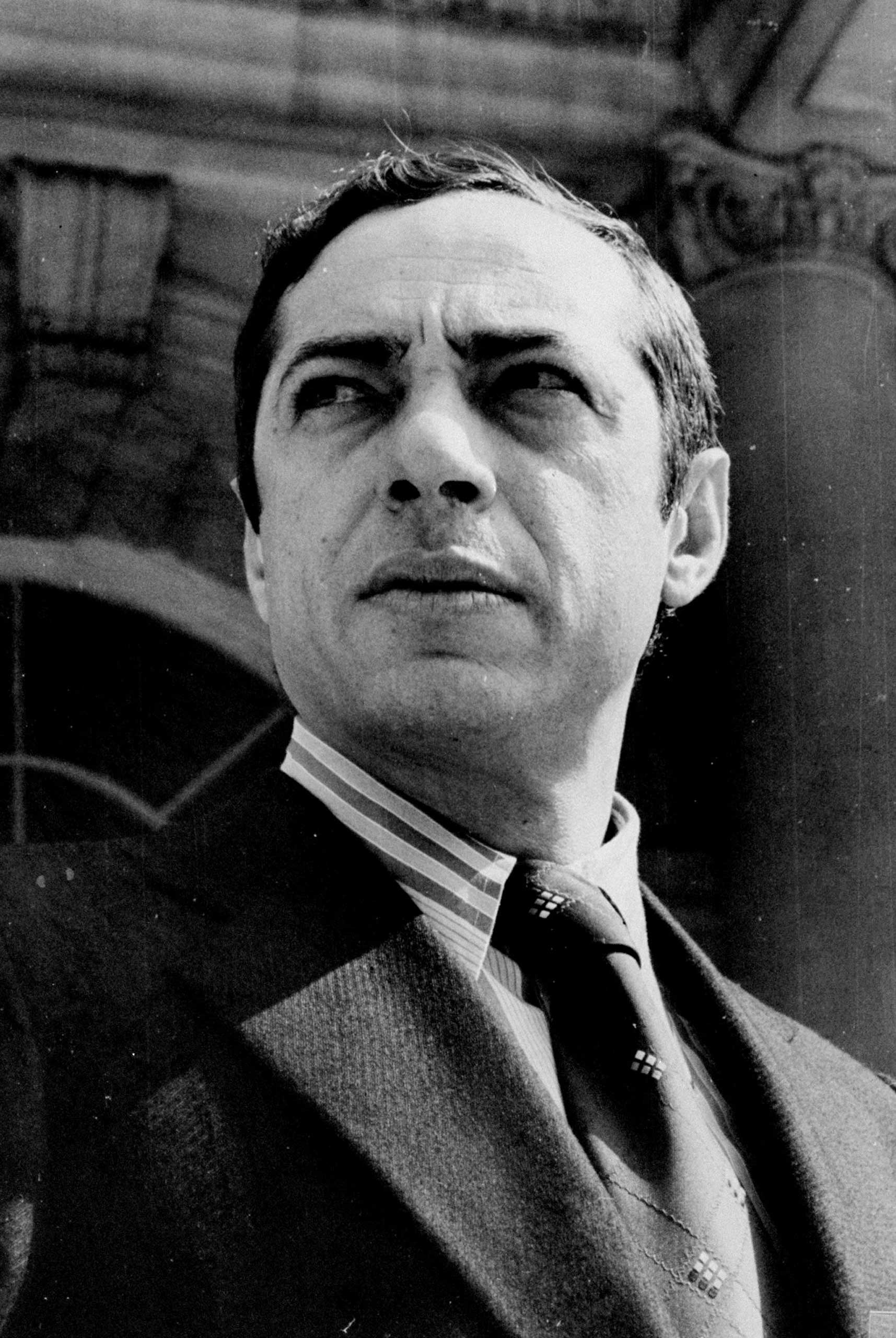

The fact that Cuomo is being considered for the presidency at all is phenomenal. Until age 46, he had never held elective office. The lawyer from Queens, N.Y., lost his first two bids for election. After his defeat in a race for New York City mayor in 1977, he was considered politically dead. No one gave him a chance when he declared for Governor in 1982. His victory three years ago was the first election he had ever won without running on someone else’s coattails. His three years in office have been relatively uneventful. Yet now, even as he carefully denies any present plans to seek the presidency, he is considered one of the Democratic Party’s shining stars.

It was only after his stem-winder at the 1984 Democratic National Convention (a speech he today regards as far too emotional) that Mario Cuomo pierced the larger American consciousness. Already this year he has been asked to speak in nearly every state; colleges beckon him with offers of commencement addresses. Democratic fund raisers say that his name is a magnet for money. Wherever he speaks, he dazzles audiences with his verbal virtuosity and moves them with the evocation of his oft-repeated theme of family: “The sharing of benefits and burdens for the good of all.” “He’s the most exciting, vibrant politician in America today,” says Senator Joseph Biden of Delaware, a man who is often mentioned as a Democratic contender.

Cuomo, for all his somewhat disingenuous reluctance, finds himself playing a central character in the uncertain saga of his party. In the Age of Reagan, Democrats are a party in search of direction. Cuomo has the potential to be the muscular philosopher-prince who can teach them to preserve what is best of traditional liberalism in an era of fiscal conservatism. He is, in fact, a kind of microcosm of the divided soul of the party. As the man who runs, as he likes to put it, “the greatest state in the greatest nation in the only world we know,” Cuomo believes that his mission is to meld old-fashioned compassion with fiscal common sense. In jest, he calls himself the founder of the Progressive Pragmatist Party. He is quick, however, to trumpet what would be its platform: a kind of frugal liberalism, conservatism with a human face. If this self-described progressive pragmatist can act as mediator between the Democratic Party’s left wing, including Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, and the assertive right, symbolized by the Democratic Leadership Council, he could become its center of gravity. In defining himself, Cuomo may help redefine his party.

Cuomo loathes labels, deriding them as “one-word summaries of an entire philosophy.” He challenges anyone to define him. “How about the money we spent on prisons?” Cuomo asks. He has built more than 6,000 new cells. “Is that liberal or conservative?” He cites his $1.2 billion transportation bond issue. “What about all the work we’ve done on highways, roads and bridges?” His voice rises. “Is that liberal? Maybe it’s conservative.” He has balanced New York’s budget but has appropriated more money for the homeless than any other state. “Tell me,” he says, as if cross-examining a recalcitrant witness in a Queens criminal court, “is that liberal or conservative?”

His soaring rhetoric, though stirring, seems to float above the realm of the practical. “We believe in only the government we need,” Cuomo says frequently, “but we insist on all the government we need.” An elegant phrase, but hardly a coherent philosophy of governing. In practice, Cuomo rarely makes the distinction between only and all. What Cuomo will tell you, though, is that government has an obligation to assist the homeless, the infirm, the destitute, to serve the poor without ravaging the middle class. “I didn’t come into this business to be an accountant,” he says. “I came into this business to help people.”

Cuomo’s character does not always coincide with his rhetoric; his politics and his persona are not a seamless garment. Cuomo is the poetic speaker who preaches the politics of inclusion yet distrusts all but a handful of people. He is the cerebral Roman Catholic who has modeled himself on St. Thomas More but can display a kind of conspicuous moral vanity. He is the immigrant’s son who talks about mercy and generosity but can be meanspirited and vindictive. Yet contradictions aside, he is that rare figure who is able to inspire, to tap into the souls of voters.

Cuomo is impulsive. He bristles easily. He boils over. He blurts things out. During the 1985 debate over the New York seat-belt law, he derided the bill’s opponents as “NRA hunters who drink beer, don’t vote and lie to their wives about where they were all weekend.” He is almost too quick, too facile, for his own good. Last year when he got into what reporters called an argument but he preferred to term a Socratic dialogue on the subject of organized crime, Cuomo said, “You’re telling me that Mafia is an organization, and I’m telling you that’s a lot of baloney.” When he read a newspaper column that suggested an Italian could not be elected President, he told a reporter, “If anything could make me change my mind about running for the presidency, it’s people talking about, ‘An Italian can’t do it; a Catholic can’t do it.’ ” Sometimes Cuomo sounds self-serving, as though he is the only man in politics for the right reasons.

Yet the Cuomo style is a mixture of warmth and wit. He is simpatico. As a reporter embarks on a question, Cuomo yells out, “I deny it! I deny it!” He describes something that irks him as “just a walnut in the batter of eternity.” In the midst of a conversation Cuomo is having with an elderly woman from Queens, his press secretary, Martin Steadman, sneezes while she is talking. “That’s a Yiddish sign,” she says, “that the person talking is telling the truth.” Cuomo turns to Steadman: “Next time, see if you can sneeze while I’m talking.”

As a speaker, Cuomo is a modern master of the ancient art of rhetoric. His repertoire includes sarcasm, mimicry, hyperbole, irony, parables, analogies and allusions. He poses questions and answers them, sets up philosophical straw men and knocks them down. He begins slowly and gains momentum; he races up the hill of one sentence and coasts down another. His timing is that of a stand-up comic. His voice can be as soothing as a late-night disk jockey’s or as rumbling as an Old Testament prophet’s. He can, on occasion, be shrill, edging toward the sanctimonious. But always one hears a man who is actually thinking while he speaks.

Cuomo sleeps only four or five hours a night. His eagerness to work, not an alarm, wakes him around 5 a.m. In a study off his bedroom, he brews a cup of coffee and settles down for an hour or so of communing with his diary (see following story). At 6:45 he gets a regular call from an aide in New York City who summarizes the morning papers. Cuomo dissects everything that is written about him. Each morning he does 17 minutes of yoga, therapy for his bad back. His official day begins when he rides to his second-floor office in the ornate elevator built to accommodate Governor Franklin Roosevelt’s wheelchair.

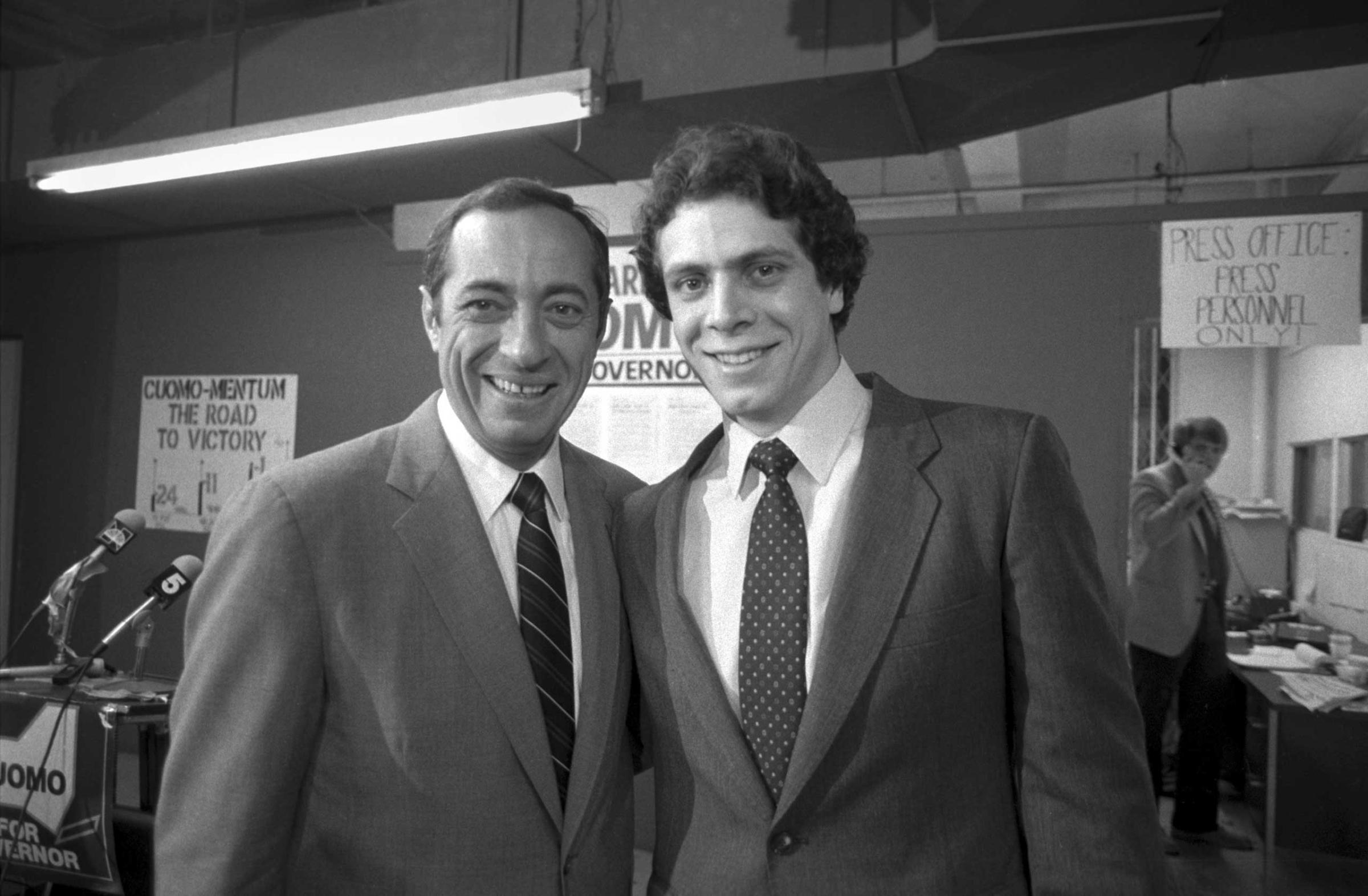

At 8:30 a.m. each Monday, Cuomo directs a senior-staff meeting of some 30 people. At one recent session, the subject of Medicaid comes up. An aide says that his administration has reached an impasse. “Impasse,” the Governor says, like a finicky lexicographer emending an improper usage, “means no progress. None of that.” After the meeting, in his office, Cuomo will punch out telephone calls himself. He rings the mayor of Niagara Falls. He is out. He calls his son Andrew, a shrewd 28-year-old lawyer who ran Cuomo’s campaign for Governor and is in many ways his father’s alter ego. The Governor mentions the name of a potential political appointee. Andrew likes the candidate and the idea. Good. It is settled.

Cuomo is a detail man who likes to do things himself. He polishes his elegant speeches and his clunky black shoes–and is proud of both. He reads the fine print in the bills he signs. There is no gatekeeper on his staff; he is the axis of the wheel. One ex-staffer says that Cuomo has created no real machine of government, has no grasp of management systems: “He runs a high- level mom-and-pop operation.”

Cuomo, the paterfamilias, gives new meaning to the term hands-on management. Consider this for supervision: his longtime aide Tonio Burgos walks into the Governor’s Manhattan office with a memorandum. “What’s wrong with your collar?” asks the Governor. The tips of Burgos’ collar are pointed up like butterfly wings. “Come here,” orders Cuomo. The Governor reaches into his desk, takes out a paper clip and twists it. He then puts a hand on Burgos’ shoulder, lifts up his collar and inserts the paper clip so that it acts as a collar stay. Same thing on the other side. “Balancing the budget was easy,” says a deadpan Cuomo as he smooths down his aide’s collar. “This was hard.”

As the Governor rode to an Albany inn to address a conference of police- union officers earlier this year, his staff counseled him not to bring up the death penalty, which he passionately opposes and has vetoed four times. In the middle of the speech, however, he put aside his notes, leaned across the lectern and said, “I know what people say. This mushy-headed liberal Cuomo, who read a book once. These macho guys who want to burn people, fry them.” He drops his voice. “I know how you feel.” He does. Cuomo’s father-in-law was paralyzed by a mugger’s attack. “Look, my mother wants revenge.” Cuomo does not. He tells them that he is for life without parole. “I’d say, ‘That’s it, Charlie, you’re going to be by yourself for 100 years.’ ” The policemen applaud.

Later, at his office, Cuomo dials a familiar number. After several rings, a low voice answers. “Mamma,” Cuomo says, “I’ve been talking about you.” He begins to tell her about the speech, but his mother interrupts, talking furiously in Italian. Cuomo translates for a reporter. Three women had been murdered the day before in Brooklyn. Animals, she calls the killers; they deserve to die. The Governor manages to calm her, then says an affectionate goodbye in Italian.

Andrea and Immaculata Cuomo came to America by boat from Naples. They had little money and no English. Mario, their fourth and final child, was born in the urban equivalent of a log cabin, the room behind his father’s grocery store. Cuomo has turned his early life into a sepia-tinted parable of a polyglot neighborhood of hard work and love. He can spin out stories about everyone on the old block: Lanzone, the baker; Kaye, the Jewish tailor; Kelly, the Irish scrap dealer.

Cuomo remembers his father working, always working. The store was open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Young Mario often helped out at night, preparing sandwiches for the early-morning construction crews. “All he thought about was working for his family,” Cuomo says of his father, who died in 1981. “I talk and talk and talk, and I haven’t taught people in 50 years of life what my father taught by example in one week.”

Mario was the studious one; he would perch himself on some milk crates in the back room and read late into the night. When he was 14 he switched from Jamaica public schools to the more demanding St. John’s Prep, and began an educational love affair with St. John’s that has lasted for more than 25 years, from prep school through college, law school and 17 years as an adjunct professor of law. Every morning, without fail, Cuomo slips on his heavy St. John’s class ring.

As much as the turning of a fresh page, young Mario loved the clean connection of ball and bat. He was a natural athlete. Baseball was his calling; he was a centerfielder, a more compact, combative version of his idol, Joe DiMaggio. Cuomo was good enough for the Pittsburgh Pirates to sign him for a $2,000 bonus to play in their Class D Georgia-Florida League. A scouting report prepared at the time singled out Cuomo for his talent and his aggressiveness: “He is another who will run over you if you get in his way.” Once, when a catcher muttered an ethnic insult, Cuomo turned and punched him in the face mask. Apart from his temper, Cuomo had a problem: he could not hit a curve ball. He knew that there was more to life than playing ball.

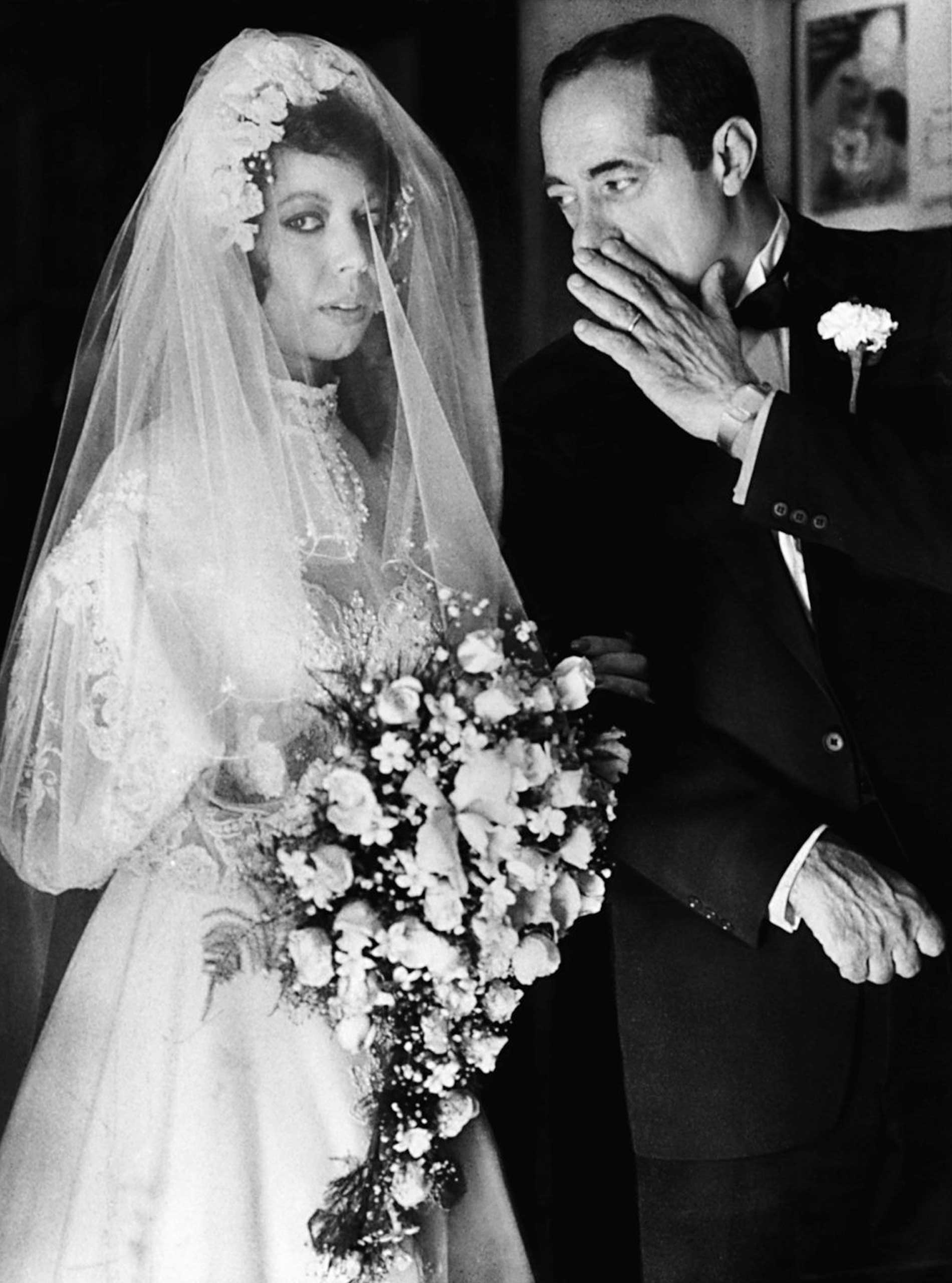

During his senior year in college, Cuomo shyly introduced himself to a popular, curly-haired girl named Matilda Raffa. She remembers him as serious and religious, the kind of boy, her mother told her, who would never hurt her. Andrew Cuomo recalls how when he first started dating, his father told him not to forget that the girl he was taking out that night was somebody’s sister. When Cuomo proposed to Matilda, he was in his first year of law school; she remembers that he gave her a lecture on the Catholic Church’s teaching about birth control.

At law school, Cuomo impressed his classmates and teachers as an intellectual duelist of fiendish cleverness. Arguing with Cuomo is like arm wrestling with an opponent who has some built-in advantage: it is hard to get any leverage. He tied for first in his graduating class and was chosen to serve as a legal assistant for a judge on the New York State Court of Appeals. He spent his time staying up late to ponder legal briefs and commuting to Queens on weekends from Albany.

After two years, Cuomo sent out dozens of letters to top-drawer Manhattan law firms. A friend urged him in applying to use his more Anglicized middle name, Matthew, rather than Mario, advice he did not take. Cuomo was rejected by every firm. He was stung. He saw their response as a clear example of prejudice against Italian Americans, and it confirmed his sense of himself as an outsider. He took a job instead with a firm in Brooklyn and gravitated toward trial work. He loved the verbal jousting, the sweet certainty that preparation paid off.

By this time, he and Matilda had had four of their five children and were living in the five-bedroom Cape Cod-style house in Holliswood, Queens, that Andrea Cuomo had built for them. Cuomo was his papa’s boy: he worked all the time. But he grew restive. He needed a cause and found one in a group of blue- collar, mostly Italian families from Corona, Queens, who were trying to prevent the city from tearing down their houses for a new school. After six years, Cuomo won a compromise that saved nearly all the homes.

His advocacy impressed Mayor John Lindsay, who asked Cuomo to mediate a dispute in Forest Hills, where middle-class, mostly Jewish families were opposed to the construction of high-rise public housing for low-income, mostly black families. Many political observers saw the assignment as political suicide, but for Cuomo it was a moral conundrum come to life, a test of neighborhood values versus civil rights. What Cuomo learned was that coming up with a simple, Solomonic solution (he proposed halving the size of the project) was a great deal easier than getting both sides to accept it. The resolution he engineered was a way station on the road to progressive pragmatism. The hothead who bruised his knuckles on a catcher’s face mask was learning the art of compromise.

In 1974 Cuomo ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic nomination for Lieutenant Governor. The decorum of the courtroom had not prepared him for the hurly-burly of the soapbox. “I was too professorial,” Cuomo recalls. Hugh Carey, whom Cuomo knew from St. John’s, was elected Governor and persuaded Cuomo to take on the largely ceremonial job of secretary of state. In 1977 Carey pushed Cuomo to run for mayor of New York City. Cuomo, overcompensating for his preceptorial manner, turned almost surly. In the campaign debates, he made Congressman Ed Koch appear to be the victim, not an easy thing to accomplish. “I was too prosecutorial,” he says. Cuomo lost the nomination, then ran on the Liberal Party line in the general election and lost again.

Carey asked Cuomo to run with him as Lieutenant Governor in 1978, and the duo won easily. Within a year, however, there was tension between them, and Cuomo began thinking about challenging his benefactor. By the time Carey announced that he would not seek re-election in 1982, Cuomo was primed. But there was one thing he had not counted on: Ed Koch. After the mayor decided to seek the nomination, Cuomo’s support suddenly became scarce.

The death penalty was a symbolic issue in the campaign. Koch and the public were for it with a vengeance, while Cuomo was fervently opposed. Voters disagreed with Cuomo but admired his principles and his chutzpah. Cuomo defeated Koch by a comfortable margin and went on to beat Republican Lew Lehrman by a slim one. Defeating Koch was a catharsis for Cuomo; he had come from way behind to upset the man whom he once thought of as his nemesis. Koch today says Cuomo has “been a superb Governor,” utilizing his talent for “communication, conciliation and consensus in an unusually successful way.” At the time, Pollster Patrick Caddell likened Cuomo to Sandy Koufax when he was riding the Dodger bench. Everyone knew Koufax had enormous potential. Then one day Koufax found his control and went from being an enigma to one of the most overwhelming pitchers ever. Cuomo, said Caddell, almost overnight became “one of the most awesome candidates I’ve ever dealt with.”

Cuomo had the good fortune to campaign during a recession and govern during a recovery. He inherited a projected deficit of $1.8 billion, which he eliminated in his first budget. New revenues allowed Cuomo to do what few Democratic Governors of New York have ever done: cut taxes. Cuomo boasts of having made the largest tax reduction in New York history, $3.2 billion over three years. He has overseen four straight balanced budgets and, despite the cranky, byzantine ways of Albany, they have been done on time.

Out of what Cuomo calls “my defense budget”–money appropriated for law- and-order–he has built more than 6,000 new prison cells for the overcrowded New York system. He has proposed a Medicaid bill that reforms the method of payment, saving the state money. New York has begun an innovative program to provide capital construction money to nonprofit groups to build housing for the homeless. It has also pioneered a variation on “workfare” programs, permitting welfare recipients to receive job training.

As a Governor, Cuomo is, in a way, handicapped by his own eloquence; his vaulting rhetoric creates equally lofty expectations. In reality, he is something of an incrementalist, creating a pattern of change in small ways. “Stone by stone, we cross the morass,” he likes to say, quoting Justice Learned Hand.

Cuomo’s critics suggest that he has not translated his popularity into programs, that he has failed to get the legislature to pass many of his initiatives. Says one Democratic official: “He never pushes the legislative leaders.” The Governor, for example, has not been able to win support for a program to clean up toxic-waste sites around the state. Cuomo’s detractors point out that the tax cut only lowers the maximum rate for personal income from 10% to 9%, and that New York still taxes and borrows more than any other large industrial state.

On average, each of Cuomo’s four budgets has grown by double the inflation rate; his 1986 budget is 30% higher than his 1983 budget. The number of employees on the state payroll has increased by more than 24,000 during his administration. Notes William Stern, former head of the state’s Urban Development Corporation: “Mario believes in government activism. That means spending rather than cutting.” Jack Kemp has dubbed the Governor “Status Cuomo.” Cuomo, says one official who left the administration, “never tackles real change.”

One force he did confront was New York’s Archbishop, John Cardinal O’Connor. Cuomo, his wife and youngest son Christopher were watching O’Connor in a television interview in 1984. Cuomo was disturbed when O’Connor asserted, “I do not see how a Catholic in good conscience could vote for a candidate who explicitly supported abortion.” When O’Connor was asked whether he thought Cuomo should be excommunicated for supporting the right to abortion, he hedged his answer. The Governor was determined to reply. His resolve was further strengthened by O’Connor’s subsequent attack on Cuomo’s Queens Democratic colleague, Vice-Presidential Candidate Geraldine Ferraro, for taking a similar stance.

The Governor’s response took the form of a lengthy, closely reasoned speech at Notre Dame in which he disputed the proposition that a Catholic public official has a duty to obey the church before the laws of the state. A Catholic Governor in a pluralistic society, Cuomo argued, should not impose his personal and religious opposition to abortion on those he governs. “To assure our freedom,” Cuomo said, “we must allow others the same freedom, even if it occasionally produces conduct which we would hold to be sinful.” The speech further estranged Cuomo and O’Connor. Today their relationship is one of mutual wariness.

The influence of Roman Catholic philosophy on Cuomo is pervasive. When he won the St. Thomas More scholarship at St. John’s law school, he began a lifelong fealty to the ideals embodied by the 16th century English scholar and martyred Chancellor to Henry VIII. In St. Thomas More, Cuomo found a fellow lawyer, a man of great gifts and profound flaws who reminded him of his own imperfections while providing a model of how to live with them. More’s famous work Utopia describes an island where both religion and reason work to support ethical norms and the aim of society is to provide in a communal way for all citizens.

Cuomo’s world view has also been shaped by the philosophy of the French Jesuit and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, whose writings were suppressed by the church until after his death in 1955. Until the early 1960s, Cuomo accepted the teaching of the priests at St. John’s that life was a moral obstacle course, a treacherous interval between birth and eternity. But in the ’60s, Cuomo says, he was liberated by the discovery of Teilhard’s Divine Milieu (a book he has “dipped into 100 times”), in which the Jesuit propounded the philosophy that God made man to embrace the world rather than reject it. This view vindicated Cuomo’s own preference for engagement with the world and confirmed his judgment that his liberal activism and commitment to social justice had both a moral and a specifically Catholic imprimatur.

Cuomo’s record as Governor and his depth as a thinker should be considerable assets in a race for the presidency. But it is neither his record nor his thinking that makes him so significant to many Democrats; it is his voice, his skill as a communicator, his ability to seize on symbolic issues. He has that most potent of political attributes, a personal magnetism that tugs at the public’s attention. “I think at this stage Cuomo is the strongest of the contenders,” says Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt, a conservative Democrat who is a potential rival for the nomination. Some are waiting to see how Cuomo will position himself. “It’s a question of which Cuomo he will try to sell,” says one Democratic strategist. “His San Francisco speech in 1984 was really an eloquent defense of the past. But if he is going to sell the pragmatic Governor who also has a heart, that’s another matter.”

At the moment, the Cuomo strategy seems to be to run for President by not running, reflecting the newest conventional wisdom that it may no longer be necessary to begin campaigning years before the nomination. In the relentless glare of the media age, overexposure can be more devastating than an undernourished organization, and the public can grow disenchanted with campaigners it knows too well. A candidate with a solid background and strong base (New York, say) might be able to patrol the sidelines–at least until near the end of 1987–and gain as a presence through his absence. With a ramshackle organization, Gary Hart upset Walter Mondale in New Hampshire. Cuomo, his advisers hope, could do the same to Hart this time around and perhaps have the staying power needed to make it all the way to the nomination. At the moment, Hart is the clear front runner; a poll for TIME last week by Yankelovich, Clancy, Shulman found that among all the potential nominees, three times as many Democrats and independents prefer Hart to Cuomo.

Although it is likely that Cuomo would appeal to voters in the urban areas of the Northeast and Midwest, traditional Democratic power bases, both his style and his message may play less well in the South and the Sunbelt, regions that are critical if the party hopes to regain the presidency. Cuomo is still largely unknown in the South and West, to party activists as well as voters.

Moreover, Southerners and Westerners may label Cuomo an “Eastern liberal.” Says one Democratic pollster: “Being from New York can be a factor because there is vague resentment of New York.” Steven Patterson, Mississippi Democratic state chairman, says that Cuomo “represents the old package, the old liberalism, warmed over from the party’s past.”

Another Democratic strategist wonders whether Cuomo’s appeal is like a wine that does not travel. “I don’t know if Mario Cuomo can go beyond the fairly limited environment he’s been in most of his life. Sure, he derives strength from his roots. But people must wonder if he can really reach beyond his own history and understand their problems out in farm country and the Sunbelt.” Says a key party leader: “If I could give one word of advice to Mario Cuomo, the word would be relax.” In the television era, when the ideal temperature for a politician is cool, Cuomo is hot; he comes across not in muted pastels but in bold chiaroscuro.

What distinguishes Cuomo as a politician is his doubts. “In 1977, when I lost, I didn’t believe that I was better than the other candidates,” he says. Cuomo cross-examines himself about his own motivations. He distrusts ambition. “I take power too seriously to be totally comfortable with it,” he says. “If all you have is the personal desire, that’s suspicious. You have to have a contribution to make.” A man who does not question himself, he suggests, should not be President.

Cuomo often says that people need to believe in something bigger, nob ler than themselves. The question that Cuomo will be struggling with next year is whether he judges himself big enough, noble enough for people to believe in. But the voters will have a more elusive task ahead of them. They will have to come to grips with Cuomo the man, searching for meaning and coherence in his mind and character.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com