Exactly 80 years ago today, on Jan. 1, 1935, the Associated Press sent its very first photograph over the organization’s brand new Wirephoto service: an aerial photo of a plane crash in upstate New York. The photo was delivered across the country to 47 newspapers in 25 states.

In an article published that day in The Bulletin newspaper, AP president Frank B. Noyes named each of the papers that had opted into the service saying, “These are the pioneers of wirephoto, which outstrips other messengers in conveying the news in pictures just as, a century ago, the telegraph came to outstrip the carrier pigeon and the pony express, and, a little more than a generation ago, the typewriter relegated the stylus to oblivion.”

Photos up to that point were largely delivered by mail, train or airplane, taking up to 85 hours in transit. AP Wirephoto could transmit a photo in minutes.

AT&T had made a previous attempt at their own photo wire service. In 1926, the telephone company had succeeded in setting up eight sending and receiving centers across the nation, which AP and other outlets had put to use. It was, however, a hugely expensive endeavor for the company and its users; after spending over $3m dollars with comparatively small returns, the service was shut down in 1933.

Before AT&T closed down its service, AP General Manager Kent Cooper had made it his mission to develop such a service in house. “KC was the father of the AP Newsphoto Service,” former AP executive photo editor Al Resch was quoted as saying in the company magazine The AP World in 1969. “He was deeply dedicated to the proposition that the day’s news should be just as thoroughly and competently covered in pictures as in words.”

Cooper prevailed, despite hefty internal opposition (the service posed a threat to Hearst and Scripps-Howard, AP member organizations that owned competing photo services) and under the spectre of the Great Depression. The story is well documented in AP’s annual report for 1934: “After discussion it was voted that Mr. Howard be informed that the Board and Executive Committee would be glad to confer with representatives of the Scripps-Howard and Hearst member newspapers, on the basis that the Board was always willing to consider any problem affecting its members and in which there was any mutuality of interest.”

The system was comprised of three main elements: transmitters, receivers, and 10,000 miles of leased telephone lines – the wires. The transmitters required first a print – AP photographers would either send in their film to be developed and printed at an AP darkroom, or develop and print it themselves using portable darkrooms. At that time, they worked mainly with Speed Graphic cameras and 4×5 film.

Once the print was made and ready to be sent, it would be wrapped around a cylinder on the transmitter. At the push of a button, the cylinder, which could hold up to 11 x 17-inch prints, would spin at one hundred revolutions per minute underneath an optical scanner. The optical scanner would shine a very thin beam of light onto the spinning print, which would then reflect light back into a photoelectric cell, which, in turn, would translate the reflections of light and dark tones into signals that would be carried across the wires.

The receiver on the other end had a similar spinning cylinder with a negative on it. As the transmission came in, the signals would be converted back into light, which was then recorded onto the negative, reproducing the original image.

AP stationed a network monitor in their New York bureau to control the sending and receiving of images. It was his job to listen to daily offerings from the member papers who would call in descriptions of the best images each outlet had to send, and then to decide which of those photos would be transmitted to which member papers at what time. Each transmission could take from 10 to 17 minutes depending on the size of the print, so the network monitor’s challenge was to decide, within the time constraints of a given day, which photos the world would see. See a dramatization of this process in the video below.

Over the next 20 years, AP Wirephoto technology would be continually streamlined as the network grew. By 1936, AP technicians had made available portable transmitters that came in two 40-pound suitcases. They were bulky and required trained technicians to run them. By the end of 1937, the stationary transmitters and receivers at the AP bureaus and newspapers were replaced with ones that were smaller, lighter, and could be plugged into a wall socket instead of taking power from a wet cell battery. By 1939, the portable transmitters were made more compact and AP had 35 units ready for use. Color transmissions, which took three times as long as black and white due to color separation, became available that same year.

Picture quality on the receiving end was continually improved and fine tuned. More newspapers signed on for the service, the network continued to enlarge. As America entered WWII, the demand for pictures – and for picture delivery – forced advances in Radiophoto transmissions. Wirephoto had also transmitted maps and charts from its inception, but these became especially valuable during war time.

Postwar, the transmitters and receivers became yet again smaller, picture quality and transmission of tonality improved, and AP developed receivers that were capable of producing positives as well as negatives, again cutting down time-to-market. By 1951, over 20,000 pictures were transmitted via Wirephoto annually.

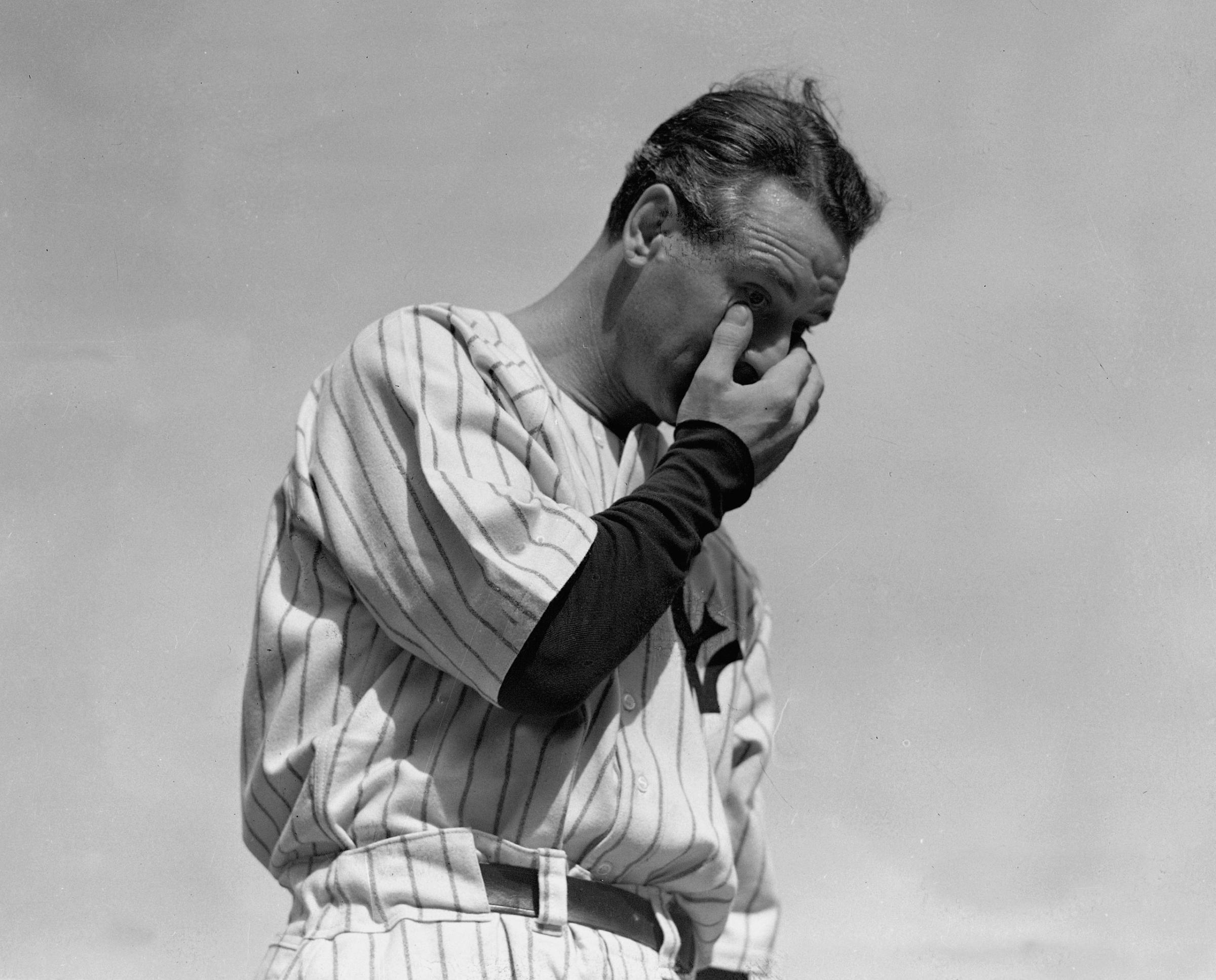

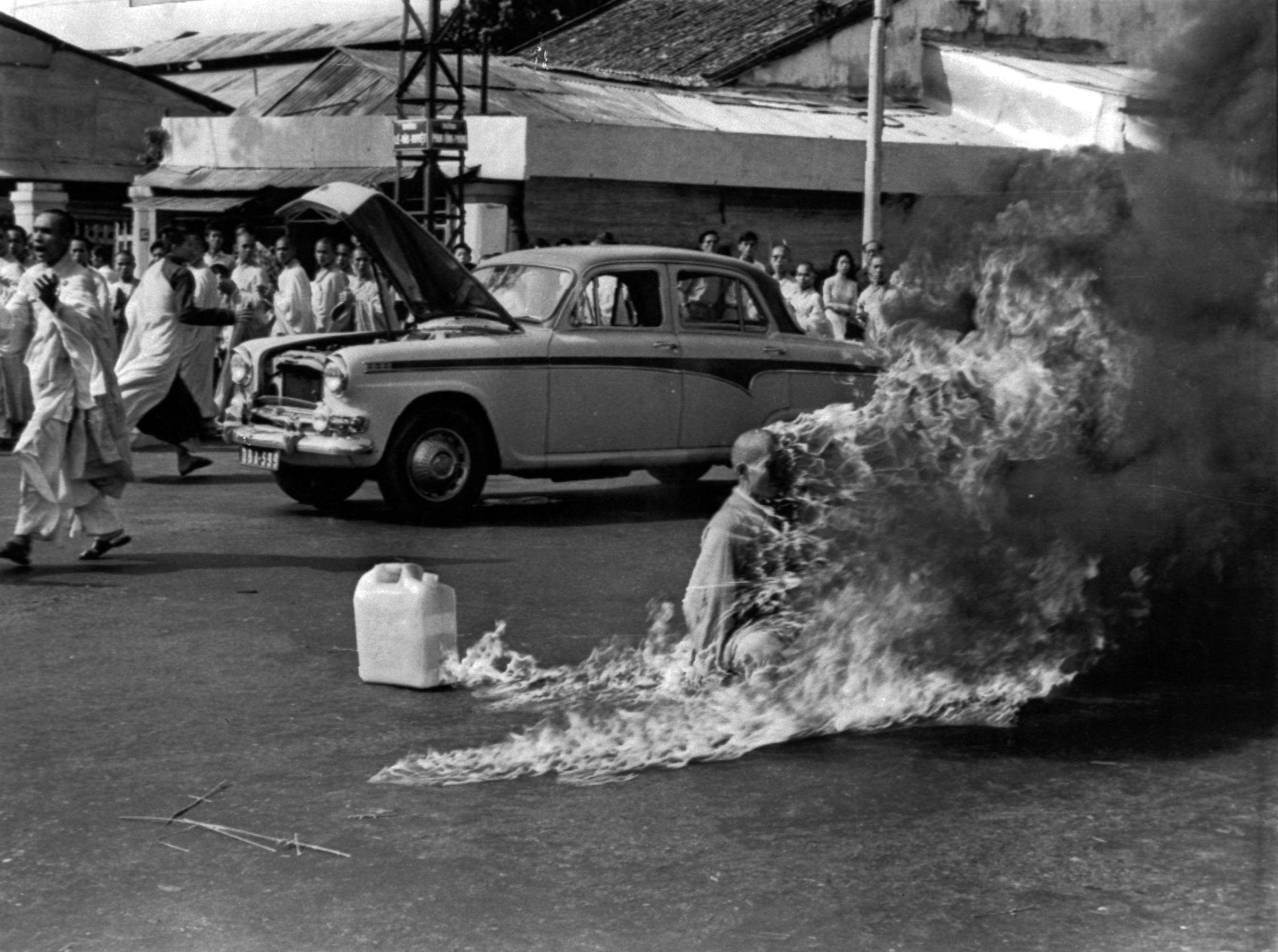

By 1963, North America and Europe were connected via a leased circuit. In the same time period, as AP began its historic coverage of the Vietnam war, its photographers were making the transition from shooting 4×5 and 120mm film to 35mm film.

Between the 1960s and the 90s there were three major leaps in technology, ultimately leading to digital transmission. The first big jump was the establishment of the Electronic Darkroom in 1978 which digitized the signals coming through on the wires. It featured computers that could crop, tone, and sharpen images as they came through. It was in a way an early, crude version of Photoshop. Operators could receive an image, edit it, and send it back out to the network without the added delay of developing a negative or making prints.

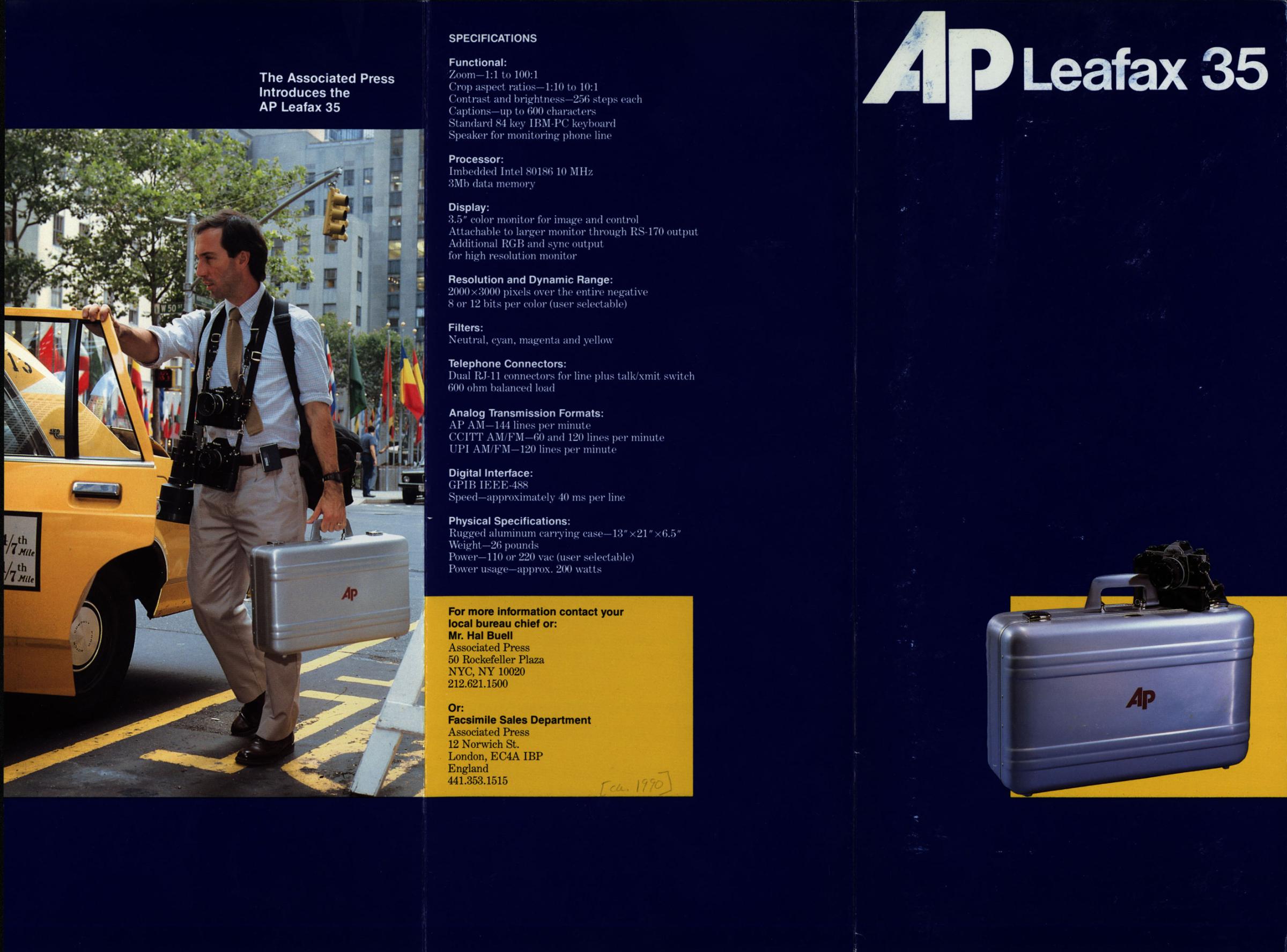

Negative scanning was the next push forward in the mid-80s with AP’s procurement of the Leafax, a compact and portable picture transmitter held in a briefcase-sized case. AP photographers could take color or black-and-white negatives, scan them into the Leafax, tone, sharpen, crop and add captions, then send them through to the network. With the exception of developing film, the Leafax eliminated darkroom work and printmaking for photographers and again cut the amount of time it took for the picture to travel from the camera to the news consumer.

“That was the first step,” Hal Buell, AP’s former head of photography, tells TIME. “The next thing was to set up a digital network which we called Photostream.” Photostream was announced in 1989, and offered all digital transmission via satellite. It reduced transmission time from 10 minutes to 60 seconds, and offered a method of delivering higher quality color pictures. AP supplied every U.S. newspaper with a Leafdesk to receive the new digital transmissions.

“We had to send a representative into every newspaper in the U.S. that took photos and show them how the digital system worked with incoming wire pictures,” says Buell. “We put these desks in every newspaper, and that not only changed the way AP handled pictures, but it changed the way newspapers handled pictures.”

AP’s first digital news photo was made and transmitted earlier in 1989 at George H.W. Bush’s inauguration by Ron Edmonds using a Nikon QV-1000c. The advent of ever more powerful computers and laptops, portable satellites, improvements in image compression, and the lightning fast evolution of digital cameras, now with possibility of in-camera transmission and video, has continued to accelerate and increase AP’s delivery of images from the late 1990s to the present. Whereas in 1951 the service transmitted 22,000 images annually, AP now transmits over 3,000 images daily.

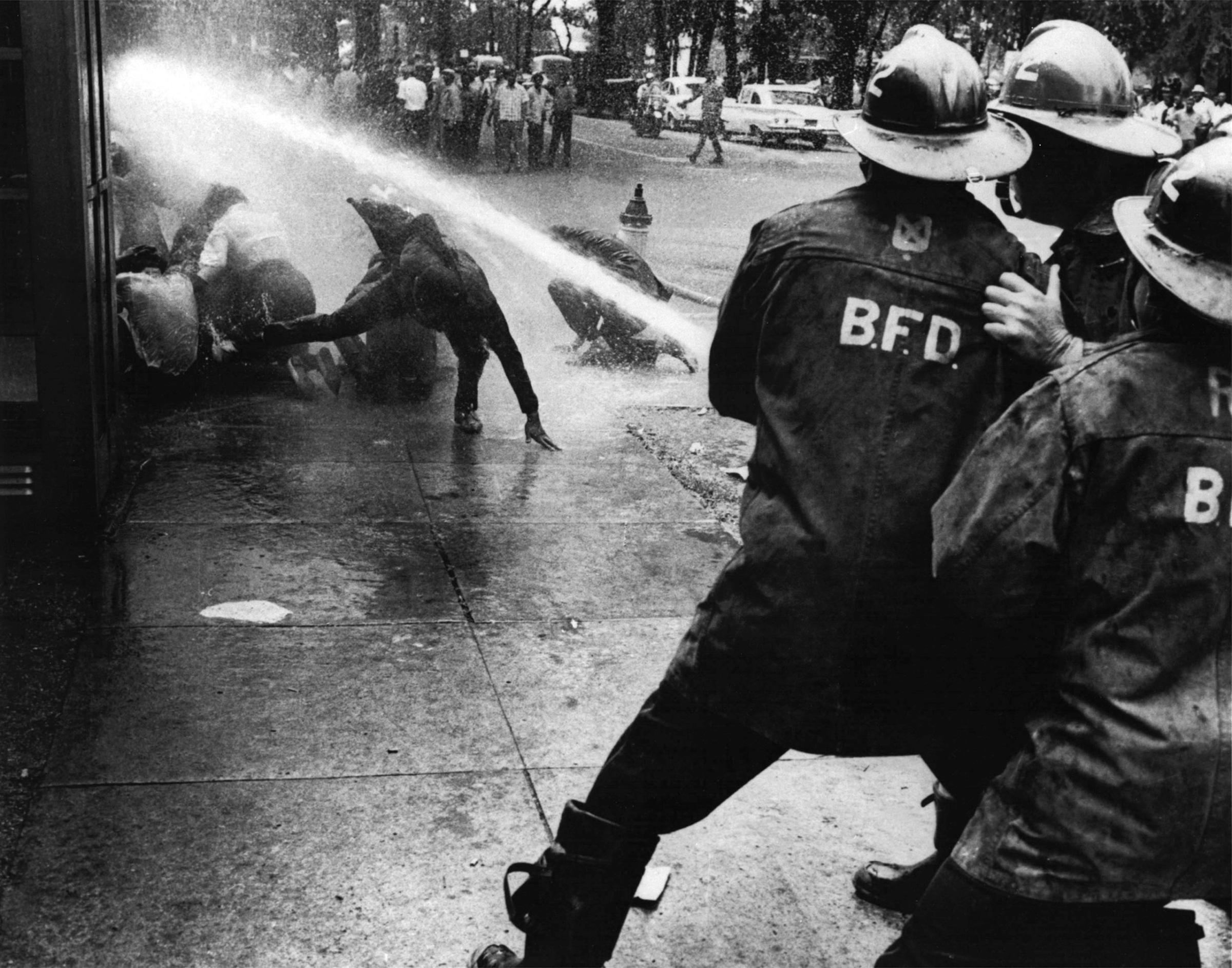

In that early 1935 Bulletin article, Noyes touched on something that was, and continues to be, essential to the news: speed, the need for which has driven the evolution of communication technology to this day. This may seem self-evident; however, as these technologies have evolved, they directly affect how news is created and how it is digested, and thus, in very profound, sometimes imperceptible ways, how we conceive of the world around us.

The launch of AP’s Photowire service initiated just that sort of weighty paradigm shift. “From Jan. 1, 1935 on, you could say that as far as the news goes, the visual had become newsworthy and capable of carrying the news, of being news,” Valerie Komor, Director of AP’s Corporate Archives, tells TIME. “Photography could be news.”

Photography is now indeed news, as is, increasingly, video. If we think of the way in which we – as news consumers – receive and read news images today, the experience feels instantaneous. Our understanding of the world is a constant, and rapid distillation of an ever increasing number of images spread over innumerable platforms. We are offered ever more perspectives, and a wealth of information. The responsibility now often falls on the reader to pace their intake of information.

“In the same way that a story can be read at the viewer’s leisure, a photograph can be contemplated at the viewer’s leisure,” says Santiago Lyon, the Vice President and Director of Photography at AP. “You are able to consider it and you’re able to have an opinion about it. And the discerning viewer won’t just look at a photograph, they’ll read a photograph, and they’ll look at all of the details in the picture and they’ll notice things and they’ll spend some time looking at a picture.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mia Tramz at mia.tramz@time.com