No one was initially more skeptical of the existence of X-rays than Wilhelm Roentgen — the man who discovered them.

One day in late 1895, the German physicist was preparing to begin an experiment with cathode rays, the glowing beams of electrons that pass through a vacuum tube when electricity is applied, which were a popular fixture in physics at the time. In his darkened lab, he covered the tube with black cardboard to hide its glow, but noticed a glimmer of light on a fluorescent screen across the room.

Curious, Roentgen “placed a sheet of black cardboard between the screen and the tube, then another, then a book of 1000 pages, then a wooden shelf board more than two and a half centimeters thick,” according to a story in the journal Physics Today. “The glimmer remained.”

At some point, he held up a small lead disk, and cast a terrifying shadow on the screen: the dark shape of the disk itself, along with the skeletal outline of the bones in his hand.

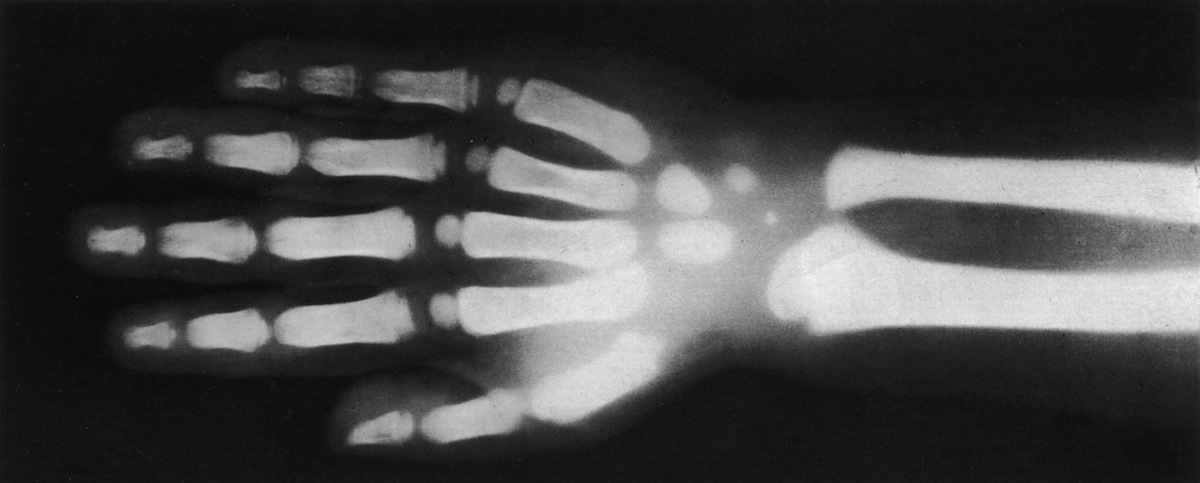

According to Physics Today, Roentgen was very late to dinner with his family that night. When he did show up, “he did not speak, ate little, and then left abruptly” to return to his lab. Afraid that he might have imagined the whole thing, he cautiously told a friend, as quoted by the journal Resonance, “I have discovered something interesting, but I do not know whether or not my observations are correct.” Eventually he summoned the courage to tell his wife what he’d seen, and enlisted her help in a follow-up experiment. Just before Christmas that year, he replaced the fluorescent screen with photographic paper and took the world’s first X-ray, a clear image of the bones and wedding ring on his wife’s left hand. She found the experience as unnerving as he had, exclaiming, “I have seen my death.”

When news of Roentgen’s discovery was published in an Austrian newspaper on this day, Jan. 5, in 1896, the monumental implications for science and medicine quickly became apparent. The New York Times picked up the story two weeks later, but couched it in skepticism that echoed Roentgen’s own, reporting his “alleged discovery of how to photograph the invisible.”

While the Times eventually wrote more glowingly of Roentgen’s discovery, neither it nor any other newspaper revealed much about the scientist himself. Notoriously publicity-shy, he turned down countless speaking engagements and stipulated that when he died, his letters and journals should be destroyed.

He eschewed fortune as well as fame: He never patented X-rays, which he thought should be freely available to other researchers and the medical community, and, according to TIME’s brief notice at the time of his death, donated the money that came with his 1901 Nobel Prize (about $40,000) to a scientific society.

Roentgen’s generosity caught up with him near the end of his life, however. By the time he died, in 1923, his unwillingness to profit from his discovery — coupled with the economic conditions that followed World War I — had left him nearly penniless.

Read TIME’s 1956 examination of the safety of X-rays: X-Ray Danger

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com