Ham Hak-joon lives alone in one moldy room at the top of a hill in Seoul, looking out on a city and back on a lifetime that have passed him by.

Now 86 years old and retired without a wife or contact with his two grown children, Ham has plenty of time to wonder how his life will end. One constant source of anxiety is who will hold a funeral for him.

He says he hasn’t spoken to his children in more than 15 years and that his only friends are, like him, poor and elderly. “I thought of donating my body to science,” he said. “At least that way I could be sure that someone would come collect me when I go.”

But instead of that, Ham has reached out to a civic group that holds funerals for people who die with no known family members, their bodies going unclaimed from hospitals or police morgues.

That organization, called Good Nanum (or Good Sharing), was formed five years ago when stories of unclaimed bodies began to circulate in South Korea.

Park Jin-ok, Good Nanum’s director, says he and his colleagues thought it important that everyone, even those without loved ones, be provided some ceremony to mark the end of their lives.

“In our country, not just living, but dying has become a source of worry,” says Park. “Elderly people who live alone wonder what will happen to their bodies. We promise that we’ll find them.”

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of bodies going unclaimed. Data released in October by the country’s Ministry of Health and Welfare found 878 unclaimed dead nationwide in 2013, up from 719 in 2012 and 682 in 2011.

Park says that his work can be emotionally taxing and that, in private moments, he is sometimes haunted by the more shocking cases he has encountered of unclaimed deceased. The mother found dead of apparent suicide, floating off the coast with her newborn baby strapped to her back. The homeless man killed when a shutter collapsed on him as he slept in a storefront late at night.

Ham wears his winter jacket, seated cross-legged on an electric blanket, the only source of heat in his otherwise frigid one-room apartment. He apologizes for the low temperature and is sheepish about his room’s musty odor. Before receiving visitors, he leaves the door open to bring in fresh air, despite the subzero temperatures outdoors.

One of three children, he tells the story of having started his adulthood in the South Korean military in the mid-1950s, driving a truck delivering ammunition to military posts on the northern outskirts of Seoul — then and today the frontline in a simmering conflict with North Korea.

He then spent years as a bus driver, traversing the busy streets of Seoul. Frustrated by how his low wages made it difficult for him to provide for his wife and two children, Ham started his own tour bus company in the mid-1990s. He borrowed money to buy three buses and hire drivers, hoping to build a prosperous business. But when South Korea’s economy collapsed in the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98, Ham’s work dried up and he went bankrupt.

It was downhill from there: his relationship with his wife soured and their marriage ended in divorce. Ashamed at having no job or money, he isolated himself from his son and daughter.

“My pride wouldn’t allow me to face them after I had failed,” Ham said. He says can’t clearly remember the last time he saw his kids in person. “I don’t even think they would know my face if they saw me today,” he says.

Ham’s only income is a government pension of around $100 per month. He used to collect scrap cardboard for recycling to earn some money, but problems with his knees have made that impossible. Because he is a father of two, he doesn’t qualify for more government assistance. In South Korea, children are expected to financially support their aging parents.

Unfortunately, that expectation does not match reality. Results of a survey by Statistics Korea released last month show that more elderly people are financially independent of their children and fewer adults who feel obligated to take care of their aging parents (31.7 this year, down from 40.7 in 2008).

Experts say the situation in each family is largely determined by their financial circumstances. “The adult children of parents who are not self-sufficient feel the pressure of filial obligation more,” says Ansuk Jeong, a Ph.D. in community psychology and research professor at Yonsei University in Seoul.

Good Nanum usually waits for around a month before cremating the corpse and holding a funeral. During that time, they post known details of the deceased on local government websites, with the hope that family members will come forward.

Social workers say sometimes bodies aren’t claimed because relatives because can’t afford to cover the funeral costs. “The funerals cost around 5 million won ($4,500), which is too much of a burden for many families,” says Park Sang-ho, a social worker in Seoul.

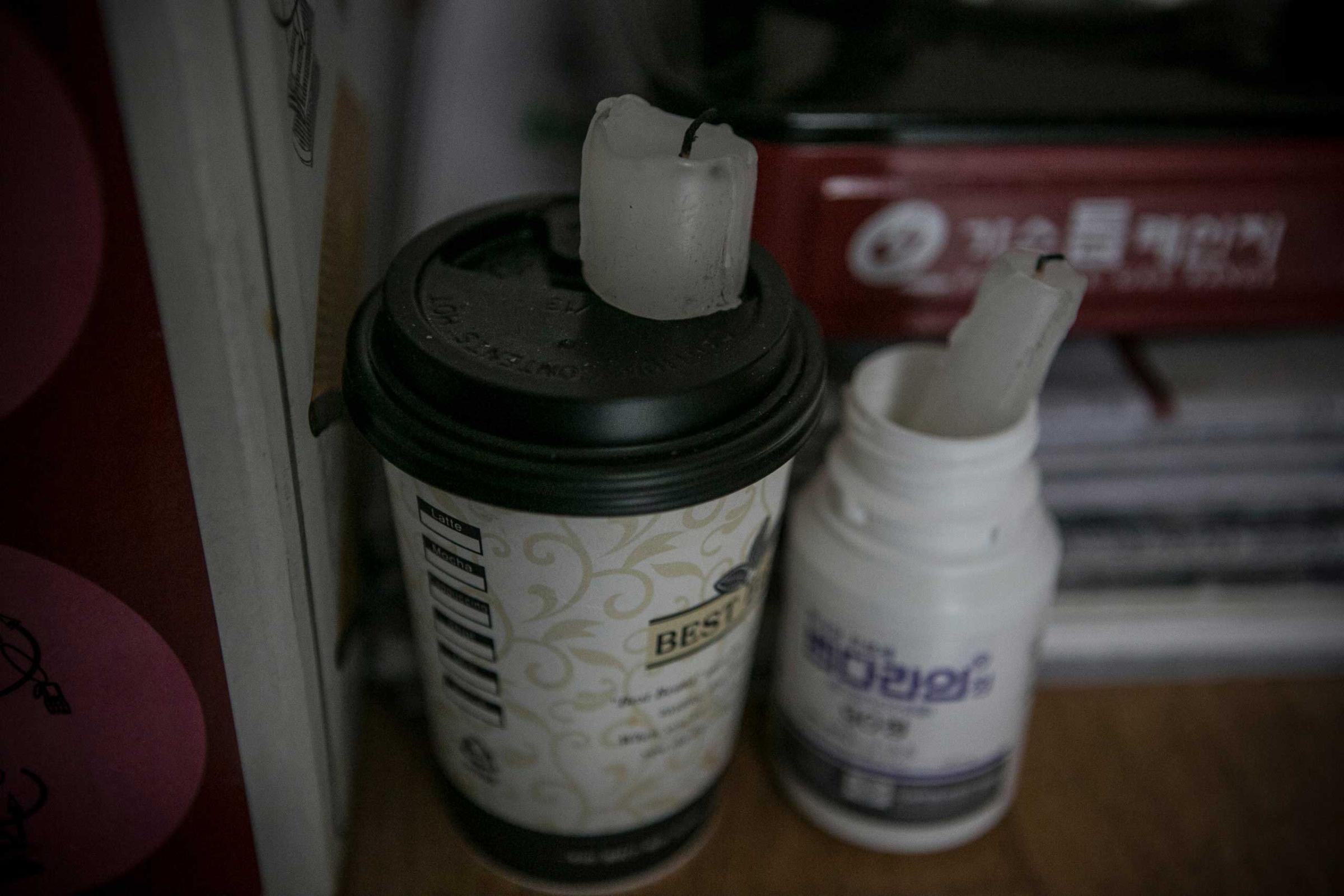

Korean funerals are normally a three-day affair, but due to a lack of staff and resources, Good Nanum holds only one-day funerals. They display a portrait of the deceased, if one is available and their identity is known. In front of the casket they display the customary drinks or snacks that the deceased may have enjoyed in life.

Ham has already prepared his funeral portrait. He says he at least is no longer worried about passing away anonymously.

“I know I won’t be all alone after I die,” he says. “That makes me live a bit easier.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com