This Christmas Eve marks an American bicentennial—the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812. It’s hardly surprising that this event has been eclipsed by holiday hubbub. As the historian Alan Taylor has written, “The War of 1812 looms small in American memory.”

Does this war merit greater remembrance? The War of 1812 was ostensibly about securing American independence against the persistent threats of Great Britain. In the decades after the Revolution, Britain contested U.S. commercial rights in the Atlantic, forcibly commandeered (“impressed”) U.S. sailors, and seemed to obstruct U.S. expansion in the West. In June 1812, Congress officially declared war for the first time in its history.

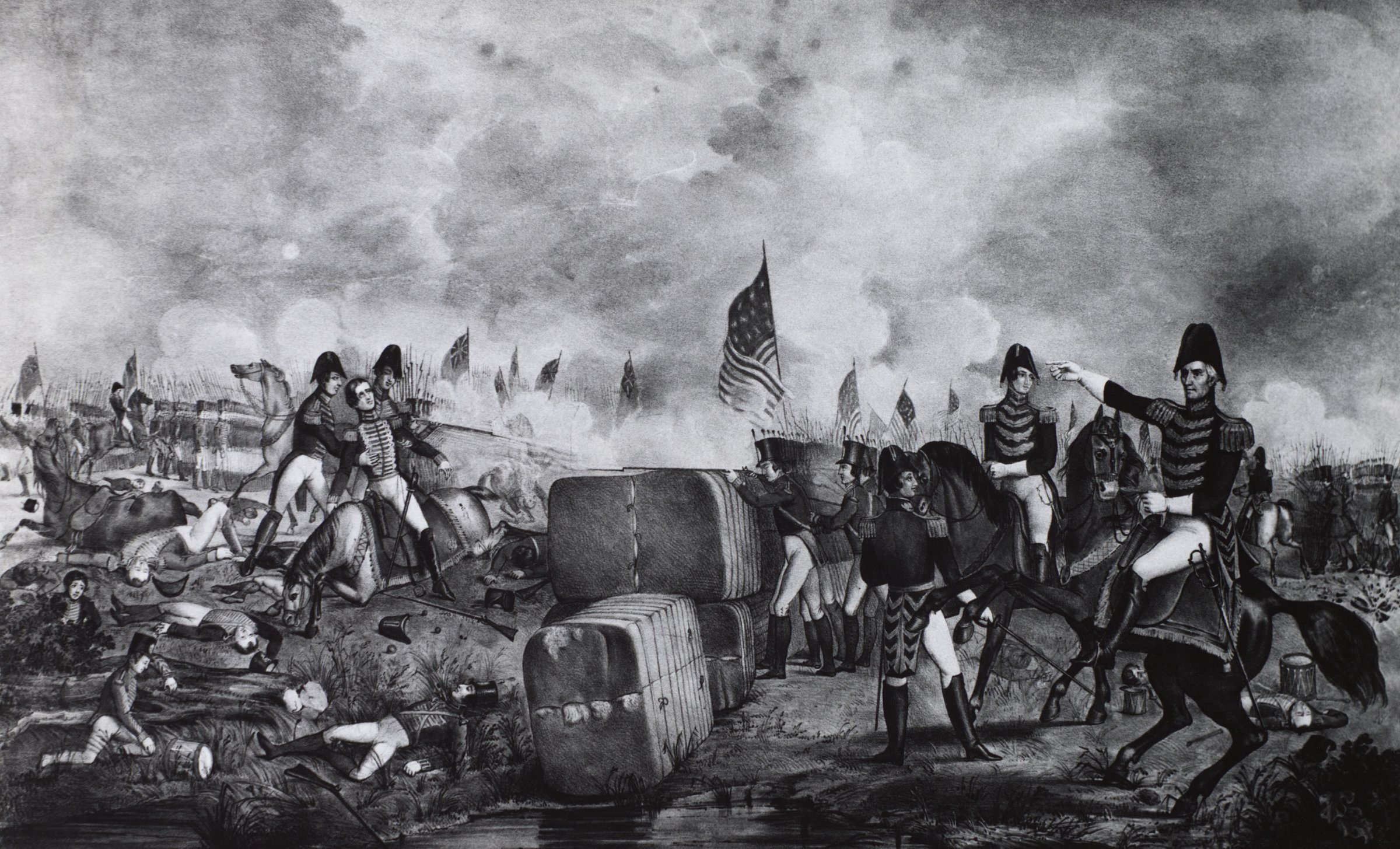

But that war was unnecessary—perhaps the first ill-advised U.S. war of choice. The War of 1812 was a series of military disasters, and its greatest U.S. victory came in the Battle of New Orleans, fought on January 8, 1815, after the Treaty had been signed in Belgium. The peace settled none of the issues that inspired the stalemated conflict.

And yet it was embraced by President James Madison and most Americans as a major victory. Instant myth was more palatable—and more useful—than genuine history. Americans pushed aside the poor planning, vicious politics, sectional division, and martial ineptitude of the war, and instead celebrated an imagined unity, virtue, right, and might. And even those who understood that the U.S. hadn’t won could take comfort in the fact that it had not lost. And by not losing to the greatest military power on Earth (no matter the mitigating circumstances of a Britain distracted by Napoleonic wars), the United States affirmed its independence. In the war’s aftermath the country experienced an unprecedented outpouring of nationalism that further obscured embarrassing facts and fueled American economic and territorial expansion.

But public memory of the war itself quickly faded. The war won some momentary prominence as the United States remade itself as a naval power in the years before the First World War. But the war itself had receded as an issue; at the 1915 centennial, Americans and Britons together celebrated a “century of peace,” not the war itself.

If we knew the history better, the War of 1812 could teach us plenty. It offers us cautionary tales about the political miscalculations of American leaders, the risks of rushing into war, and the dangers of military arrogance and ineptitude.

The U.S. military effort faltered from the start, when the aged General William Hull surrendered Detroit without a shot being fired, though he commanded superior forces. Hull was later court-martialed and ordered shot, though President Madison issued a reprieve. Combat on the U.S.-Canadian borderlands was characterized by atrocities; everywhere fighting was inconclusive.

But the war’s aftermath was devastatingly conclusive for Native Americans who mostly favored Britain. For many Indian nations it was a struggle for their survival (against intrusive American “pioneers”). The British used Native American soldiers to contest U.S. expansion; Native Americans used the British alliance to protect their homelands. Yet in peace, Great Britain abandoned its Indian allies. The War of 1812 was thus as much an Indian-white conflict as it was a U.S.-British war, and Native Americans were its biggest losers. The tribes’ defeat and treaty fraud opened Indians lands to white settlers, and a series of removals (numerous “trails of tears”) forcibly relocated five Native American nations and over 50,000 Native American people west of the Mississippi. White settlement of these vacated territories simultaneously spread King Cotton and slavery into the Deep South.

Since the end of the War of 1812 in the year 1815, the U.S. has fought many more wars (only four of them constitutionally declared, and none declared since 1942). In resurrecting its unimpressive memory, we might learn from its lucky victory as well: Short wars are best, particularly when followed by long periods of peace.

Matthew Dennis is professor of history and environmental studies at the University of Oregon. He is the author or editor of five books, including Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar, and is currently at work on American Relics and the Politics of Public Memory. He wrote this for Zocalo Public Square. Zocalo Public Square is a not-for-profit Ideas Exchange that blends live events and humanities journalism.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com