This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

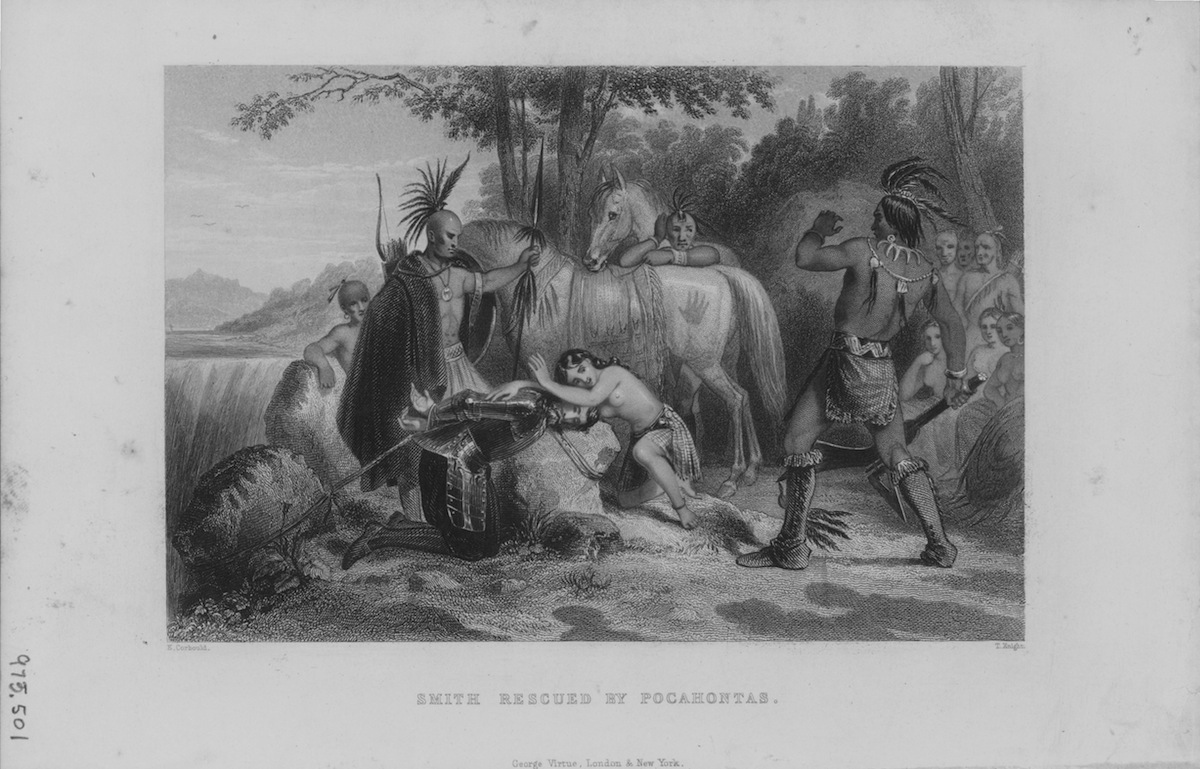

In late December, 1607, Captain John Smith was dragged before the paramount chief of the Powhatan people of Virginia. His abductors dragged boulders into the center of the native longhouse, and pulled Smith’s head down on to them. For most of the two hundred people gathered in the smoke-filled gloom of the hut, this was their first sight of a European.

As Smith lay prostrate, his guards lifted their war clubs above his head, waiting for the command to execute the prisoner in their traditional manner — by beating the brains out of his skull. Then, from out of the shadows, a young girl of perhaps ten or twelve emerged, naked from the waist up, and with only a wisp of black hair hanging down from the back of her shaved head.

The girl turned to the chief with a familiarity that suggested she knew him well. She did, for he was her father. The girl pleaded that the stranger’s life be spared. The Englishman understood little about what was being said, for his comprehension of the Algonquian language was still rudimentary.

The chief considered his daughter’s appeal. He was an old man, perhaps sixty or seventy years old, broad-shouldered, fit and powerfully built for his age. The Englishman had no option but to await the judgement that would soon seal his fate.

This encounter between Smith, an English soldier and adventurer, and the native “princess,” is one of the most enduring legends of the early colonization of America. The only European witness to the event was Smith himself, and this account of his “rescue” by Pocahontas has been questioned by historians ever since he first made it public, seventeen years later.

Smith’s autobiography, The True Travels, covers his life before he arrived in Jamestown. It includes descriptions of his extraordinary adventures as a mercenary soldier fighting the Ottomans, of being captured and sold as a slave, and time spent sailing as a pirate. A detailed examination of his life story and his other writings, suggests that we can generally rely on his accounts.

So did this encounter with Pocahontas really happen? Well, yes and no. As an experienced soldier, being “rescued” by a twelve-year-old girl would only open him to ridicule. So Smith had little to gain from making his liberation public knowledge at the time.

It now seems likely that John Smith wrote what he believed was true, but he misunderstood what was happening. He was facing only a mock execution, during which he was ritually “killed,” and then “re-born” into the tribe. Pocahontas’s father was making Smith a minor chief — a weroance — within the Powhatan tribe.

However, this infamous legend is not the only time that John Smith claims to have been rescued by Pocahontas. A couple of years later, Smith was staying with a group of his men at the chief’s village, Werowocomoco. As usual, Smith was trading beads and copper trinkets for food to see the colonists through the winter. By this time, however, relations between the Powhatan and the English were stretched to the breaking point, and tensions were running high.

Smith had loaded his bartered corn onto his ship, but the tide had ebbed, and the vessel was left high and dry on the mud. So Smith decided they should spend the night in a native longhouse. Pocahontas slipped into the hut under cover of darkness to let Smith know that her father would soon send food for them, but that he had also ordered his men to kill them as they ate.

Smith understood the risk Pocahontas was taking, for he wrote that “if [Chief] Powhatan should know it, she were but dead….” Just as Pocahontas had predicted, “eight or ten lusty fellowes” arrived with platters piled high with food. They asked Smith and his men to extinguish the lighted tapers they used to fire their muskets, because the “smoake made them sicke.” It was an odd request, because the longhouse was already filled with wood smoke. Smith grew ever more suspicious. As a precaution, he made the Powhatan taste every dish before they would eat it.

By midnight, their ship had lifted clear of the mud. Smith and his eighteen men cautiously made their way back to the river, their pistols and muskets cocked at the ready. It had been a close call, but Smith now understood the chief’s real intentions.

The real hero of the hour, however, was Pocahontas. She almost certainly risked her own life, by warning John Smith of the danger that he and his men were in at the hands of her father.

Peter Firstbrook is the author of a new biography of John Smith, “A MAN MOST DRIVEN: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Founding of America” (Oneworld Publications).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com