For young Ed McCree, enslaved on a thousand-acre Georgia cotton plantation, Christmas and New Year’s Day 150 years ago were like no other he had ever known. This child and the other men and women in bondage had always cherished Christmas. There was a week off from the unrelenting and ruthless work in the fields and barnyards; young pigs and cattle were slaughtered; and peaches and melons, still sweet from the summer, were pulled from the wheat straw and cottonseed that kept them fresh. New Year’s Day typically brought back the drudgery of daily life on a large plantation and Ed McCree, a child around 10, would be again forced to carry buckets of water to the men and women working in the fields.

The difference that December 1864? William Tecumseh Sherman’s Union Army had just marched across Georgia through the rice plantations of the low-country and reached the seaport of Savannah, offering it to President Abraham Lincoln as a Christmas present.

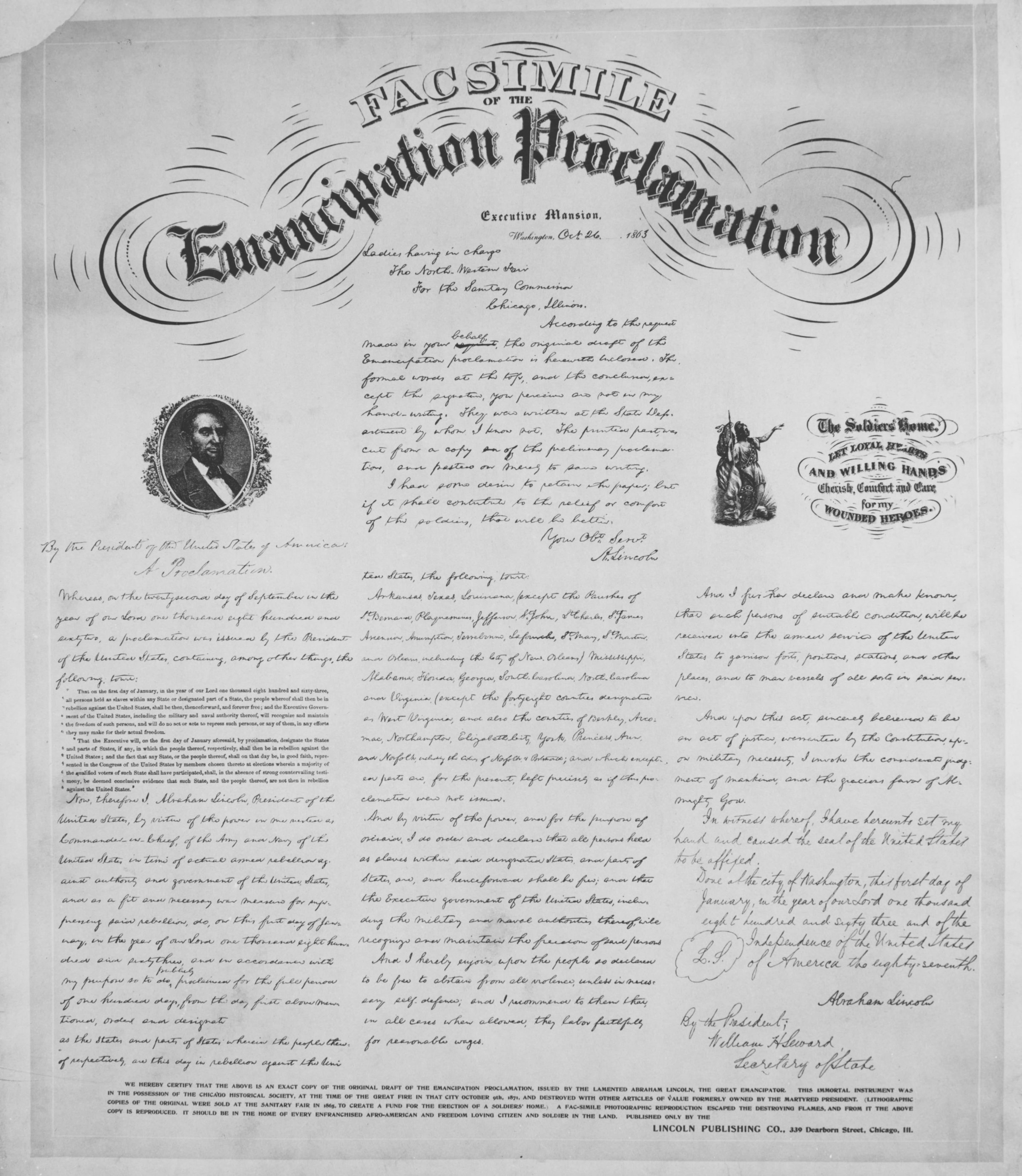

New Year’s Day 1865—and those in the two years previous—were among the most poignant and pregnant with new beginnings in American history. Ever since Lincoln had signaled his intent in September 1862 to declare slaves in rebel states emancipated as of New Year’s 1863, the possibility of freedom for African-Americans in the South had been hanging in the air, depending on the war’s progression.

I’ve long been fascinated by this transitory period of anticipation, in part because some of my ancestors were living under slavery and grappled with what it meant to be emancipated either by their own actions, or by decree. It’s also always struck me as tone deaf to argue that the Emancipation Proclamation or the Army’s earlier “contraband” policy that freed the slaves it came into contact with were merely symbolic or cynical acts. (Lincoln didn’t seek to free slaves in border states that stayed in the Union, critics are quick to point out.) As Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists contended in a rebuttal to those who posited the perfect as the enemy of the good (and a rebuttal worth repeating in the context of gradual progress on a host of landmark issues ranging from segregated schools to wartime human rights abuses): It matters where the nation officially comes down on moral issues, even if it is not ready or able to completely live up to its professed ideals.

African-American communities already held traditional church services on New Year’s Eves, but they took on a special meaning as the country welcomed in the watershed year of 1863, becoming the predecessors of today’s Watch Night services. In Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and the many free black communities in other cities and towns, African-Americans gathered to anticipate the moment the United States finally would declare itself at war with slavery and not simply disunion. Overton Bernard, a white, pro-slavery minister, described with dismay the Watch Night he witnessed in Union-held Portsmouth, Virginia, in response to what he described as Lincoln’s “unwise and unconstitutional” proclamation: Black families packed the A.M.E. church until well past midnight to pray, to sing, and to hope. In his diary, Bernard hoped that somehow emancipation would be averted as even the promise of freedom had caused the town’s blacks to become “idle and impudent” and ready to challenge their place in society.

The next day some 5,000 men, women, and children marched and rode horses, hoisting banners and flags in celebration of freedom. They celebrated despite the fact that troops from New York jeered them and disrupted their march at rifle and bayonet point and also despite the fact that Portsmouth was not covered by the proclamation, given that it was under Union control before Lincoln made his announcement. The condition of the enslaved in Union-held areas would be “left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued” because Lincoln wanted to make it clear that his emancipation order was meant to injure secessionists more than the institution of slavery.

But the significance of this decidedly imperfect decree was still electric. It is often said that the Emancipation Proclamation only freed slaves where the Union lacked authority to do so (and where the commander-in-chief could get away with it on his own as a wartime exigency), but to blacks in Portsmouth, the mere promise of freedom was so tantalizing that it was cause for celebration.

At the same time, abolitionists in the North were also throwing parties laden with expectation. In Medford, Massachusetts, businessman and activist George Stearns opened his vast estate for an affair he called “the John Brown party.” Unveiling a marble bust of the radical antislavery revolutionary whom he had helped to fund and arm, Stearns played host to a storied assortment of public intellectuals, including trailblazing abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips; Julia Ward Howe, whose “Battle Hymn of the Republic” had inspired northern soldier and civilian alike; and the transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson and his friend Amos Alcott, who brought his daughter Louisa May (later known as the author of Little Women). Like the free blacks at their Watch Nights, the partygoers spent New Year’s Day waiting for word that Lincoln had actually signed the document and had begun, in their minds, to redeem himself for his previous inaction and timidity on the central moral issue of the day.

But back in Georgia, on the plantation in Oconee County that held Ed McCree and his family captive, the Emancipation Proclamation was still nothing more than a theoretical abstraction that New Year’s Day of 1863. While it effectively meant the United States government no longer considered Ed the property of his owner John McCree, the proclamation was not known to any slave on the plantation. As 1863 dawned, the Union Army was too far away—two years away, to be precise—to be in a position to deliver on the proclamation’s promise to Ed, and it is one of the horrific cruelties of history to think of all the hardship slaves still endured while awaiting their promised deliverance.

When it did come, the deliverance from slavery would be experienced by most African-Americans in the South very suddenly. Sometimes men and women forced the issue by escaping slavery whenever federal armies got close enough to afford them the opportunity. Other times it came with a group of soldiers showing up at the plantation out of the blue and passing out hams and shoulders from the smokehouse as they took some for themselves.

Sherman’s March to the Sea from Atlanta in late 1864 took the Federals right through the McCree plantation before Christmas. After the troops had passed, Ed remembered his owner gathering his former property before him and beginning to state what they had longed to hear their whole lives: that they were free. The young boy didn’t actually hear what was said as he remembered bolting at the first words and running “around that place, a-shouting at the top of my voice.”

Something draws me to that moment of emancipation Ed McCree experienced 150 years ago, two years after it was initially proclaimed. Emancipation was the beginning of a host of decisions and challenges for Ed and his family. The entire world the former slaves knew and had learned to survive, especially Georgia and South Carolina’s “Kingdom of Rice,” was gone. Should the family stay where they were and try to make a new life there, or should they follow Sherman’s Army and see where it led? Even if they were slaves no more, the Emancipation Proclamation did not make African-Americans citizens, or endow them with many of the core rights enjoyed by other Americans. Even many who’d hoped for slavery’s abolition also hoped people like Ed would, once free, leave the country in which they were born, and which their sweat had helped build and make wealthy, in order to “go back to Africa.” For some members of my extended family back then, uncertainty about their situation and what their future in the United States might hold was enough for them to go to Canada.

Still, in honor of all the folks for whom emancipation suddenly marched their way as 1864 came to an end, we are putting a decidedly Savannah flavor into the traditional dish of cowpeas and rice in our household’s New Year’s celebration this year. Rather than black-eyed peas, my New Year’s hoppin’ John will go by its Gullah name, “reezy peezy,” and will feature Carolina Gold Rice and low-country red peas, a staple for slaves in the region. We will enjoy the dish as a tribute to the resilient spirit of the thousands who found themselves traveling a new road to find their way in a new, unknown America.

Christopher Wilson is director of the program in African-American history and culture at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. He also is director of experience and program design and founded the museum’s award-winning educational theater program. He wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zocalo Public Square. Zocalo Public Square is a not-for-profit Ideas Exchange that blends live events and humanities journalism.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com