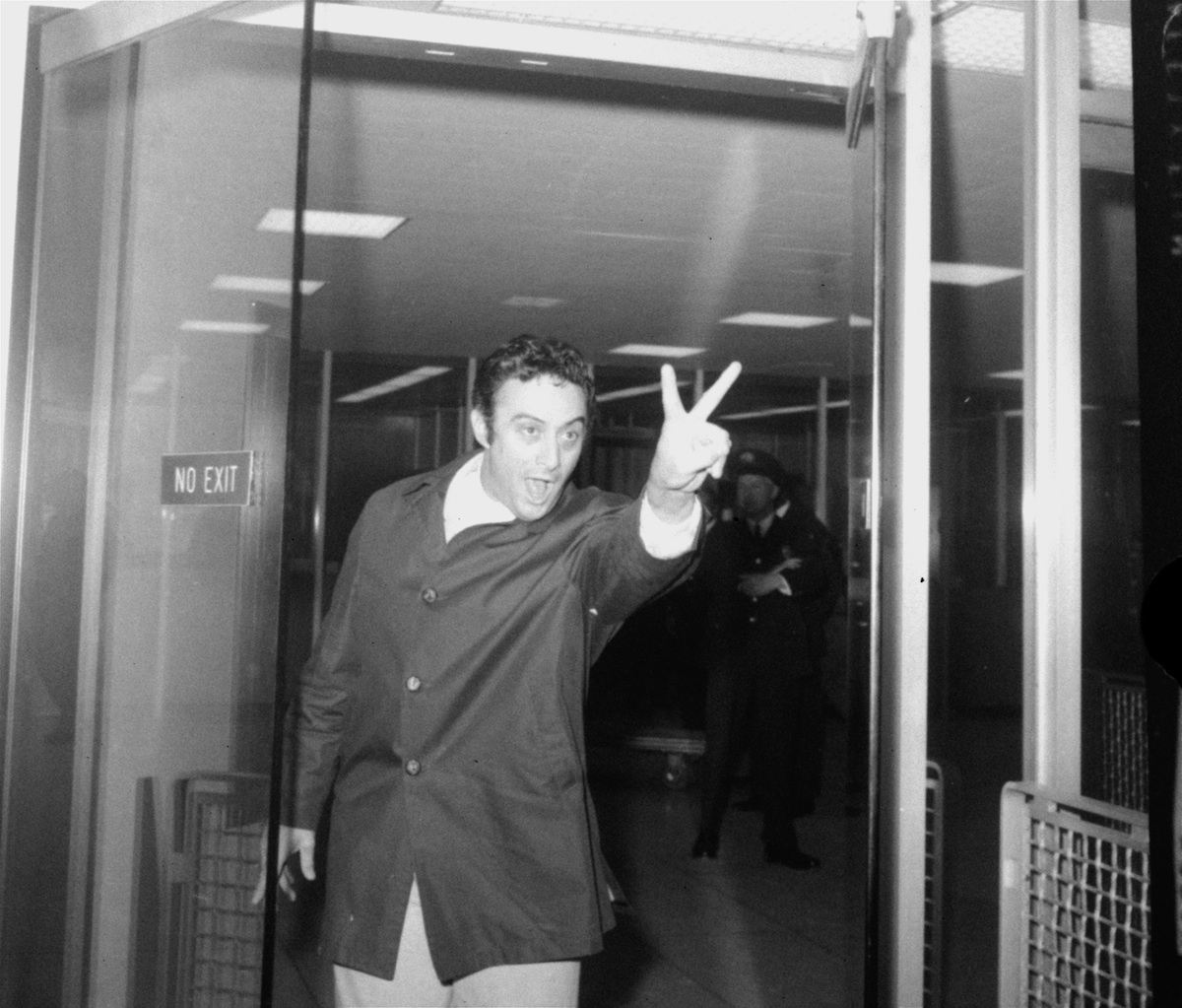

Reading about Lenny Bruce’s arrest for obscenity 50 years ago makes me think about a popular sketch Amy Schumer recently did on her Comedy Central show. On Dec. 21, 1964, Bruce was sentenced to four months in a workhouse for a set he did in a New York comedy club that included a bit about Eleanor Roosevelt’s “nice tits,” another about how men would like to “come in a chicken,” and other scatological and overly sexual humor.

How does this relate to Amy Schumer? In the sketch called “Acting Off Camera,” Schumer signs up to do the voice of what she thinks will be a sexy animated character, because Jessica Alba and Megan Fox are doing the voices of her friends. When she arrives to work she sees that her character is an idiotic meerkat who defecates continuously, eats worms and has her vagina exposed. She says to her agent, “My character has a pussy.” Schumer is the first woman to say that word on Comedy Central without being censored, a right she fought for. Her struggle was commended by the press for advancing feminism because the word had been banned even though four-letter words for male genitalia were given the O.K.

A word that could have landed Bruce in the slammer 50 years ago is now available for public consumption, and its inclusion into the cuss-word canon is applauded. These days each of George Carlin’s “seven words” seems quaint. There is nothing so raunchy, so profane or so over-the-top that it could land a comedian in jail.

However, they have other reasons to censor themselves — namely Twitter.

The most dangerous thing that a comedian has to face today is offending political correctness or saying something so racist or sexist that it kicks up an internet firestorm. In 2012, Daniel Tosh made a rape joke at a comedy club, which everyone on the internet seemed to have an opinion about. Many were offended and he later apologized for the joke. Just last month comedian Artie Lang tweeted a sexist slavery fantasy about an ESPN personality and was met with harsh criticism. Saturday Night Live writer and performer Leslie Jones, a black woman, also took heat for making jokes about slavery; her critics said they were offensive, but she defended her comments, claiming they were misunderstood. Most of this exchange took place on Twitter.

This is a common cycle these days and one that can derail a comedian’s career (just look at what happened to Seinfeld alum Michael Richards after his racist rant became public). It’s also something that comedians are hyper-aware of. “I stopped playing colleges, and the reason is because they’re way too conservative,” Chris Rock said in a recent interview in New York magazine (referring to over-prudence, not political ideology). “Kids raised on a culture of ‘We’re not going to keep score in the game because we don’t want anybody to lose.’ Or just ignoring race to a fault. You can’t say ‘the black kid over there.’ No, it’s ‘the guy with the red shoes.’ You can’t even be offensive on your way to being inoffensive.” In a world where trigger warnings are becoming popular, how can a comedian really push the envelope?

In the interview, Rock says this policing of speech and ideas leads to self-censorship, especially when he’s trying out new material. He says that comedians used to know when they went too far based on the audience reaction within a room; now they know they’ve gone too far based on the reaction of everyone with an Internet connection. Now the slightest step over the line could land a comedian not in the slammer but in a position like Bill Maher’s, where students demanded he not be able to speak at Berkeley because of statements he made about Muslims.

That’s the difference between Lenny Bruce and someone like Leslie Jones. A panel of judges decided that Bruce should face censorship because of what he said. Now Leslie Jones gets called out, but the public is the judge. Everyone with a voice on the internet can start an indecency trial and let the public decide who is guilty and to what degree. (The funny truth is, depending on whom you follow on Twitter, the party is usually universally guilty or universally innocent.)

What hasn’t changed as we’ve shifted from “obscene” to “offensive” is just how unclear the scenario could be. The Supreme Court famously refused to define “obscene” but instead said they know it when they see it. The same is true of “offensive.” One comedian can make a joke about race or rape and have it be fine, another can make a joke on the same subject matter and be the victim of a million blog posts. There was even an academic study to determine which strategies were most effective for making jokes about race.

Whenever one of these edgy jokes makes the news, a rash of comedians come to defend not the joke, necessarily, but that the person has the right to tell it in the first place. The same thing happened at Bruce’s trial when Woody Allen, Bob Dylan, Norman Mailer and James Baldwin all showed up to testify on Bruce’s behalf. Bruce never apologized for what he said. Though he passed away before his appeal could make its way through the courts, he received a posthumous pardon in 2003. Then-Governor of New York George Pataki noted that the pardon was a reminder of the importance of the First Amendment.

In 50 years a lot has changed, but comedy, like the First Amendment, really hasn’t. There are always going to be people pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable, because that’s what we find funny. What has changed is who is policing that acceptability — and that makes a big difference. We no longer have too-conservative judges enforcing “community standards” about poop jokes, telling people like Lenny Bruce that they can’t say one thing or another. Instead, today’s comedians are policed by the actual community, using the democratic voices of the Internet and social media to communicate about standards around race, religion, sexuality, gender and identity. The community doesn’t say comedians can’t offend, but that they’ll face consequences if they do. Their First Amendment rights are preserved and, though it may get in the way of the creative processed once used by people like Chris Rock, online feedback can often lead to productive conversations.

In a world where nothing is obscene, it doesn’t mean that things can’t be offensive, as murky as both those ideas might be. At least we’ve taken the government out of comedy, which seems to be safer for everyone. Now they can stick to dealing with the important things, like Janet Jackson’s nipple.

Read TIME’s original coverage of Lenny Bruce’s conviction, here in the archives: Tropic of Illinois

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com