You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

Walk along La Rampa, the main drag in what used to be Havana’s version of a sleek 1950s American suburb, and every other bombed-out house seems to be sprouting a sign in its weed-filled garden, a table loaded down with secondhand Barcelona Football Club T-shirts. One woman sits by a rack of pirated DVDs, while her neighbor advertises DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHS (FOR VISA OR PASSPORT). Someone has a sign up promising to repair your Rolex or Seiko watch, and a little handwritten notice in front of a crumbling terrace shows prices for coffee and orange juice (nothing else). Just a block or so off the busy street, a piece of paper announces, in English, ROOM FOR RENT. APRIL 18 AND 19. That was months ago.

You might be walking through a homemade rough draft of free enterprise that’s being updated and revised daily. Nothing is hidden, but there’s very little in the way of advertising, presentation or even fresh goods. A ’52 Buick rattles past with a FOR SALE sign in its back window. It’s long been legal to sell these old clunkers (many of which can fetch $25,000), but what’s new as of 2011 is that Cubans can now sell late-model Kias, for $35,000–an impressive sum in a country where a high-ranking official earns $30 a month.

At a two-year-old private Indian restaurant called Bollywood, not far away, someone is talking about a friend who’s found a Spaniard to buy (quite legally) his decaying villa for $140,000–bringing in as much as he’d otherwise make, if he were an average worker, in 583 years. Three years after President Raúl Castro opened new doors to buying and selling, more than 300,000 Cubans are now their own bosses, trying to learn capitalism on the run, often with the help of supplies or remittances from loved ones abroad.

Just a few blocks up La Rampa, far from the old hotels associated with Frank Sinatra and Meyer Lansky, you come to a dark, state-run, Soviet-era department store. Carefully laid out in its windows are exactly four tubes of chewing gum, three bags of potato chips and one can of Vita Nuova pasta sauce. Inside, a single flimsy piece of Hello Kitty underwear sits in a dusty display case.

In a show of revolutionary spirit, anticipating the country’s annual celebration of the fall of Fulgencio Batista’s regime in 1959, someone has put up some letters on the store window, spelling out WE SALUTE THE 54TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE TRIUMPH OF THE REVOLUTION. But somehow the final R has gone missing, so the sign celebrates only the triumph of EVOLUTION. A flourish of zesty Cuban irreverence–or a mark of what the irreverence is always up against: never-ending shortages?

It’s hard to say. In Cuba’s revolution, nothing seems to go as planned, and all you’re left with is a droll and often melancholy comment on how little anyone is cheering.

The Cuban Paradox

For half a century now–A period spanning the terms of 11 U.S. Presidents–both the Cuban government and its people have been used to looking in opposite directions at the same time; Cubans “are not minimalists when it comes to paradox,” as Cuban exile and Yale professor of history Carlos Eire has written. “We like our paradoxes rich and complex. The more labyrinthine, the better.” The latest chapter in this long-running tragicomedy finds the government trying to maintain the state-run economy–and strict political control–even as it encourages its people to practice self-employment. To an observer, it can look as if the state is simply hoping to off-load its huge economic problems upon its 11 million citizens: Castro has said he will release roughly 1 million people from the official workforce–almost 1 in 5–in the next year or two, even as the state continues to import 80% of its food and the average wage purchases a fourth of what it did in the not-so-rosy days of 1989.

Thus it’s possible now to sell new cars; it’s just very difficult–you need a permit and a lifetime’s official income–to buy them. It’s finally possible for dissidents to leave the island, but no one knows how they’ll be treated on their return. When an exiled Cuban now in Canada returns for a visit, all his relatives can meet and greet him–except for the one who serves in the army, who stands to lose his job if he talks to a “foreigner.”

Cubans today are free–at last–to enjoy their own version of Craigslist, to take holidays in fancy local tourist hotels, to savor seafood-and-papaya lasagna with citrus compote, washed down by a $200 bottle of wine, in one of the country’s more than 1,700 paladares, or privately run restaurants. They’re free to speak out against just about everything–except the two brothers at the top–and they strut around their capital in T-shirts featuring the $1 bill or Barack Obama in his “Yes we can” pose, even (in the case of one woman leaning against the gratings in Fraternity Park) in very skimpy briefs decorated with the Stars and Stripes.

Yet as what was long underground is now aboveboard, and as capitalist all-against-all has become official communist policy, no one seems quite sure whether the island is turning right or left. Next to the signs saying EVERYTHING FOR THE REVOLUTION, there’s an Adidas store; and the neglected houses of Old Havana sit among rooftop swimming pools and life-size stuffed bears being sold for $870. “Nobody knows where we’re going,” says a trained economist whose specialty was market research, “and people don’t know what they want. We’re sailing in the dark.”

Warming to his theme–he left government service when he noticed he could earn more in four hours of selling cookies than in a month of high-level official work–he goes on: “If you’re talking about Cuba today, you have to say that we combine the worst aspects of socialism with the worst aspects of capitalism.” His eyes flash with sardonic delight. “The worst of socialism in terms of oppression and denial of basic human rights. And the worst of capitalism in terms of exploitation and inequality!” The result is a limbo in which everyone seems to be robbing Pedro to pay Pablo.

The Ageless Island

Many years ago, I visited Cuba six times in seven years; like so many over the decades, I couldn’t resist the effervescence, the beauty, the spirited sophistication of the place. The day after I returned from my first trip, in 1987, I went to my travel agent in California and booked a second trip; Cuba was a riddle of exuberant dilapidation and gleeful disenchantment that was impossible to solve. Nothing and nobody worked, but the system hobbled on, almost in spite of itself; the people I met could hardly have been more sparkling, even as they told me their lives were out of Dante’s Inferno. Pundits on both sides of the Straits of Florida ritually traded insults and abstractions, predicting the imminent downfall of leaders in both Havana and Washington, but the real story–thick with contradictions, complications and rending human ironies–seemed to be taking place on the streets.

Over the course of my stays in the late 1980s and early ’90s, I witnessed the country enter its notorious “special period” after the collapse of its Soviet sponsors in 1991; I visited friends in prison who said they were living better there–guaranteed food and comfort–than on the outside, and much of the time the only foreigners I saw were North Koreans, walking in pairs, with pictures of their “Great Leader” Kim Il Sung on their lapels. Haunted by the paradoxes of a suspicious, openhearted, quicksilver island furiously running in place, I wrote my first novel on this gorgeous country shaped like a long, extended claw.

Nowadays, of course, Canadians and Europeans fill the refurbished colonial hotels around the beautifully restored squares of Old Havana. I flew to Havana directly from L.A. last year, on a charter flight operated by United. In 2011 alone, roughly 400,000 Americans flew straight to the island, and remittances from Cuban Americans accounted in 2012 for $5.1 billion, or three times the amount the Cuban government pays in salaries to its 4 million workers. The streets of Havana are vibrant and bustling as they never were before–and as not so many other streets are in Latin America or the Caribbean. But the sentences that greet you are, to a shocking degree, the same I heard in 1987. An old local joke has received a small upgrade (to borrow the euphemism the government deploys for its stop-and-go shifts): “We’ve found solutions for three big problems: free health care, free education and, lately, free enterprise. Now we just have to find breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

As Castro tries to do anything to generate income–his elder brother Fidel, who stepped down in 2006, is widely assumed to be almost posthumous–each season brings some new hedged opportunity. But after 54 years of broken promises and reversals, most Cubans seem to regard optimism, even relief, as the most forbidden contraband of all. The latest liberties afforded them are reminiscent of a father giving his son the keys to the car decades after the son has begun taking it out on the sly.

The children–and grandchildren–of the revolution remain as adaptable and animated as ever, but the only real shift seems to be that they are exchanging cash where for decades they exchanged goods and services in an impromptu barter economy. Go to a private restaurant, and after your meal, when you look for a taxi, the owner will call his brother–a medical student–so as to keep the fare in the family. A woman will spot some lemons in a neighborhood agro-pecuario, or farmers’ market, and instantly buy them all up to share with the elders she knows who can’t get there by themselves.

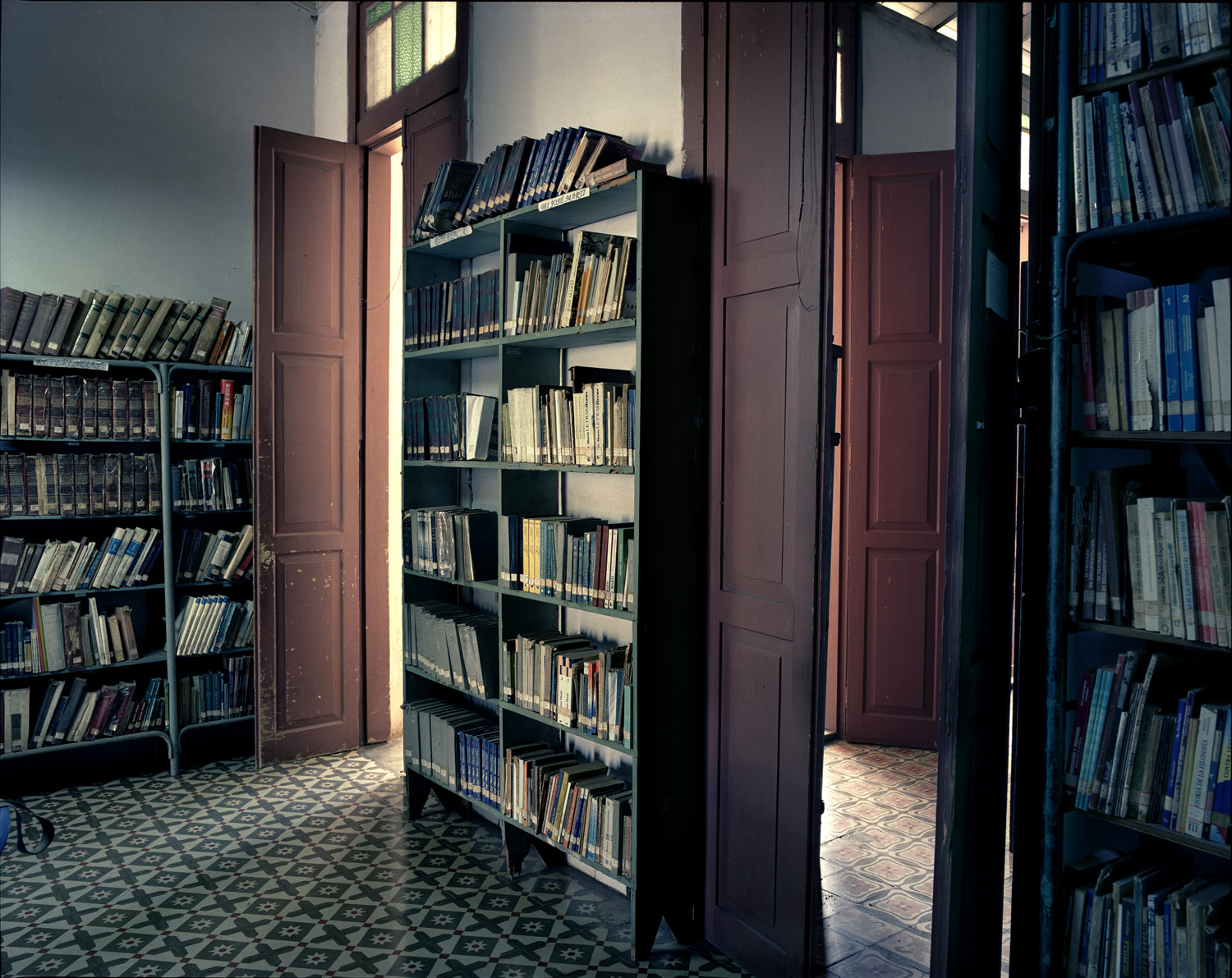

Cubans have long specialized in solidarity and community when it comes to working around the government, bound together by the skeptical warmth of compañeros locked up in a steerage compartment of the Titanic. But now the government seems to be competing with its people as fast as the people try to keep up with the whims of the state. The gorgeous Cuban section in the Museum of Fine Arts is a state-of-the-art showpiece that would not look out of place in Dallas or Zurich. But toilet paper is rationed there. And if you want to wash your hands, you have to wait for an old woman to appear, pour some drops of mineral water in your palm and then squeeze out some soap from a hotel-room minibottle before extending her own palm for a tip.

Outside Havana, inevitably, life clops along more as it’s always done. In the farmers’ town of Artemisa where, a quarter of a century ago, I saw Fidel harangue the masses as torrential rains drenched us all, the trim, freshly painted houses look much as they did then or, perhaps, as they might have before the revolution. Bicycles far outnumber cars, and banners extolling the revolution flutter from a large Chinese restaurant across from the central church. There may be less of the glitter and opportunity of Havana, but there’s also less of the restlessness and stress. Huge avocados go for 20¢, half the price they fetch in the capital. “For some people,” says a man with little patience for the revolution, “Cuba is close to paradise. They say, ‘Sure, this isn’t heaven. But you know what? I don’t have to work. I don’t pay rent. Rum is cheap. I don’t need a heater. I’m living in a beautiful tropical island. Who needs freedom?'”

The country’s celebrated health care has won admirers throughout Latin America and the Caribbean even, it’s said, among right-leaning governments. By now the revolution has exported doctors to more than 75 countries, and when Haiti was hit by its devastating earthquake 3½ years ago, Cuba was said to be the first nation to send medical aid, despite its own myriad problems and shortages. Yet typical of the paradoxes that haunt the island is the fact that the very excellence of its medical facilities has led to unintended consequences: Cuba’s population is aging and shrinking so fast that one man in his 50s predicts he’ll soon be living in a “wheelchair paradise.”

By 2025, according to the National Statistics Office, Cuba will have the oldest population in Latin America or the Caribbean; 1 in 4 of its citizens will be over the age of 60, and the universities will have lost more than 30% of their students. For a revolution that is already being run by octogenarians, the prospect of even more dependents and fewer candidates for free enterprise is not a happy one.

Everywhere in Havana you see old people on the streets, shaking tins at foreigners, trying to sell copies of the party newspaper Granma for 120 times the official price, sitting next to near empty supermarket carts close to midnight, hoping to flog a bag of popcorn or two. One of Fidel’s proudest claims not so long ago was that his country, unlike its capitalist neighbors, had no beggars or people living on the streets. Nowadays, senior citizens in Havana may technically have homes to return to, but they look and act like homeless people, barely able to survive on pensions of $6 a month.

The darker irony of the revolution, mounting over the decades, is that the country looks more and more like the nest of decadence and inequality that was Cuba before Fidel. After its rulers decided to try to save the revolution by selling it after the end of Soviet subsidies in 1991, the doors were thrown open to tourism, and a record 2.8 million visitors flooded the streets in 2012, bringing up to $2.5 billion in revenue.

Yet they’ve also brought drugs and the lure of prostitution, as well as the very gap between rich and poor that Fidel staged his revolution to erase. Where once the country tried to sell its glorious “rebel youth” past, now it relies more on its older (in fact, colonial) history. Women dress up as slaves for tourist cameras in the refurbished Plaza de Armas, and horse-drawn carriages pad over cobbled streets, as if Cuba’s one selling point is its very out-of-dateness. As locals realize that the best way to support themselves in the new economy is by becoming a minstrel, a guide or a paid companion to a tourist, they can easily feel, more than ever before, that the ultimate revolutionary goal is to be a foreigner.

Cuban Calm

For decades now, Cuba’s great resource has been its people, whose unquenchable wit and verve have somehow sustained them even as everything seems to collapse around them. There’s still a Saturday-night vitality to the place, a sense of style and creativity that seems able to keep making something out of nothing. A Ministry of the Interior official here is a small woman with huge, turquoise nails that go oddly with her uniform; a police officer is a woman sporting a flamboyant blue barrette.

As one old man notes, foreigners find it hard to believe that Cubans can greet their unending hardships with satirical amusement rather than sheer rage. On a sweltering summer afternoon, 60 people line up in the sun, uncomplaining, for a single ice cream each. Even 65 years ago, the Cistercian monk Thomas Merton, who had a spiritual awakening in Cuba, noted, “For a people that is supposed to be excitable, the Cubans have a phenomenal amount of patience with all the things that get on American nerves and drive people crazy.”

The paradoxical consequence of this, of course, is that the government does not seem to worry too much about a Caribbean Spring or outright popular revolt. You still see signs here and there proclaiming SOCIALISM: TODAY, TOMORROW, ALWAYS, but in many places the old cry of “Socialism or death” seems to have been replaced by “The fatherland or death.” And for Cubans trained for years in irony and brilliant improvisation, it’s not hard to see that the sign above one building shouting, UNITY, PRODUCTIVITY, EFFICIENCY is listing exactly the qualities most needed and most absent in Cuba today.

“Havana has always been a city of beautiful facades,” a local architect tells me, and he’s speaking literally. But facadismo, as it’s called, can have wider implications. The country’s brightly colored surfaces may be as deceiving as the government’s signs of braggadocio. And everything is in permanent flux. Devouring tasty hotcakes at a stylish private restaurant called Chaplin’s Cafe, I learn that it is owned by Roberto Robaína, who for six years in the 1990s was Foreign Minister. One day, sitting above the Malecón, the 4-mile (6.4 km) road that follows the S of the sea, I hear a Cuban cry out, “Look!” The long, black Soviet-made limo juddering past was once one of the leader’s official cars, he says. Now it’s just another taxi that anyone–anyone with money–can ride in.

An Aging Country

At the core of all the ironies, though, is a vacuum. Every single Cuban I speak to, from those barely out of their 20s to those close to 80, expresses concerns about the young. “All they’re interested in is fashion and iPhones,” I hear from old and young alike; even those who can’t stand the system claim to having known more pride in it, and more sense of purpose, when they were young in the ’70s. Those who recall the brutality and corruption of life before the revolution tend to be more forbearing toward the chaos now, but 5 Cubans out of 6 have never known anything but the shortages and convulsions of Castroism.

“In the 1990s, when we suffered from a lack of things,” says a man who in recent years joined an evangelical church, “it was a real material crisis. But now it’s deeper. We have a spiritual crisis. People have lost hope.” On every other street you see women dressed from head to toe in the pure white robes of an initiate in Santeria, the Afro-Caribbean religion that was long a secret force across the island; again and again, strangers start talking to me about Jehovah or even Allah. “People are turning to these things now because they give them something the revolution can’t,” says a man close to 80 who fought with an important revolutionary group in the ’50s. “The party should think about that.”

The deeper problem, especially for the young, is that there’s every incentive not to get an education or a good, official job. In a country where a surgeon has to bicycle to work while a man selling fake cigars can dine, quite literally, on caviar, the government has done a fine job of educating its citizens and a terrible job of putting that education to use. “I tell my students, ‘I know you can make more money now by driving a taxi than by being a good architect,'” says Mario Coyula-Cowley, a professor of architecture at Havana’s Higher Polytechnic Institute for 45 years. “But that will not always be the case. At some point architects will be properly regarded, and we will need good ones.”

A tourist and currency-exchange economy is not the kind to encourage the honesty and dignity the government keeps insisting on. “Things are better than before,” says a former lawyer in her 40s. “But I’m afraid. Capitalism makes people hard. Cubans see how to get ahead, and they’re starting to change.”

Into the Dark

As it looks toward the future, Cuba could take heart, on paper, from China and Vietnam, both of which have retained a political grip on their people while giving them incentives to make money. One morning in Havana, I’m greeted by a full-page headline in Granma trumpeting Raúl Castro’s visit to his East Asian colleagues; his son Alejandro has served as a liaison with China. But Ricardo Torres Pérez, a professor at the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy at the University of Havana (and recent visiting scholar at Harvard and Ohio State University), points out that China has a strong government as well as a thriving economy and that both China and Vietnam have young and growing workforces, natural resources–as well as a freedom from embargoes–that put them in a very different situation from Cuba. Besides, like every other Cuban I talk to, he notes how different the habits of East Asia are from Cuba’s, perhaps especially in the areas of discipline and precision. “When it comes to culture and core values, we have more in common with the economy of the U.S.,” he notes.

The free-and-easy subversiveness in which Cuba specializes is another reason an Arab Spring seems unlikely to break out here. According to one man who follows politics closely, there are 30 or more opposition groups on the island, but each has only a few members, and none is interested in working with the others. “And what they’re proposing is so elitist, so far above the ground–like these website postings–that they cannot connect with the anger of the people.” There’s neither Twitter nor Facebook in the country to mobilize crowds and, he points out, neither an Aung San Suu Kyi nor a Vaclav Havel. But the deeper problem may be the elegant urbanity with which the man records his disenchantment, as if at a Manhattan dinner party. “Look,” he says, “we’re a Latin people. We like life. In Asia, maybe, some people will say, ‘We will die to make a point.’ We’re not into self-immolation.”

For 14 years, Cuba’s shattered economy has been propped up by Venezuela, which sends roughly 110,000 barrels of oil a day to the island in exchange for Cuban medical personnel and teachers. Like many in Latin America, Venezuela’s leftist leader, Hugo Chávez, saw Fidel as an elder statesman and hero who stood up to the Yanquis for more than 50 years. Soon after Chávez’s death from cancer in March, his handpicked successor, Nicolás Maduro, promised that he would continue his mentor’s policies toward Cuba and that the two countries would spend $2 billion this year on “social-development projects.” Still, Chávez’s early death reminded Cubans that the slightest change could bring the prospect of a dreaded sequel to the special period.

Raúl Castro, now 82, has always been seen as less prideful and doctrinaire, if less charismatic, than his brother, who’s five years older; he rules in prose, not in Fidel’s combative poetry. And when Castro announced in February that he would not seek re-election in 2018, all eyes turned to his presumptive successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel, a 53-year-old technocrat and former military man who served as a party official in areas where there were abundant opportunities for foreign investment. Even as Castro spoke of term limits and referendums in the future, Cubans began to imagine, at last, a pragmatic leader born after the revolution–and one not named Castro.

For now, though, there’s no one to give Cuba a stirring sense of itself, a winning story, as is sometimes said of Obama’s America. The fact that the revolution keeps showcasing portraits of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos, dead for 46 and 54 years, respectively, underlines the absence of fresh heroes. Castro, known as the Flea when he was young, replaced 64 of Fidel’s 68 ministers when he took over the top position in 2008 and quickly implemented reform measures his brother had only talked about. But the low-key university dropout lacks his sibling’s dialectical skills, especially when it comes to redefining socialism so that it includes competition.

“As I see it, there are basically three options for the future,” says one Habanero who’s never left the country, “and all of them are horrible. I call them the North Korean, the Afghan and the Russian versions. The North Korean one is that the grandson of the big guy, who’s got very quickly promoted and is now a general in the army, takes over. Becomes our Kim Jong Un. The Afghan one is some guys in the military take control and become tropical Taliban. Set up a military council. And the Russian one is that some Vladimir Putin comes in from the army.” Predictions are notoriously unreliable in counterintuitive Cuba, but even this naysayer claims that Cuba’s pride in its independence–the nationalism that has grown with the revolution–means it may not go the way of Starbucks and American Express soon.

Meanwhile, among the broken streets of central Havana, a matron shuffles along the road called Virtues, carrying two teddy bears to try to sell. ROOMS FOR RENT, says a sign on a bashed-in building, by the HOUR/DAY/MONTH. Unlit dining rooms are turned into impromptu beauty salons, and out of one blackened apartment, near a wall on which someone has painted VIVA FIDEL, a skeletal hand emerges to drape some gold chains in front of a customer in a spotless white T-shirt. My very last night in Cuba, the electricity goes off across most of downtown, and the city becomes just shadow figures inching through the pitch black, lit up occasionally by silent flashes of sheet lightning. Much as I remember it in 1991, in fact. Free enterprise may be breaking out on every side, but for now it’s very hard to see it in the dark.

Witness Cuba's Evolution in 39 Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com