Sony Pictures Entertainment said late Wednesday that it’s pulling The Interview, a comedy about two journalists tasked with killing North Korean ruler Kim Jong Un. Sony’s move came a day after a cryptic message appeared online threatening attacks against theaters that played the film, and several weeks after hackers first breached Sony’s system and posted troves of private emails and other data online.

Shortly after Sony decided to scrub The Interview, a U.S. official confirmed to TIME that American intelligence officials have determined North Korea was behind the Sony hack, though no evidence has been disclosed.

Here’s everything we know for sure about the Sony hack, up until now.

What happened?

On Nov. 24, Sony employees came to work in Culver City, Calif., to find images of grinning red skulls on computer screens. The hackers identified themselves as #GOP, or the Guardians of Peace. They made off with a vast amount of data (reports suggest up to 100 terabytes), wiped company hard drives and began dumping sensitive documents on the Internet.

Among the sensitive information the hackers divulged: salary and personnel records for tens of thousands of employees as well as Hollywood stars; embarrassing email traffic between executives and movie moguls; and several of the studio’s unreleased feature films. More is likely to come, as Sony Pictures Co-Chair Amy Pascal said the hackers got away with every employees’ emails “from the last 10 years.”

MORE: The 7 most outrageous things we learned from the Sony hack

And the attack has already affected other companies: Secret acquisitions by photo-sharing app Snapchat, for instance, have been made public thanks to leaked emails from Sony Pictures CEO Michael Lynton, who sits on Snapchat’s board.

Who did it?

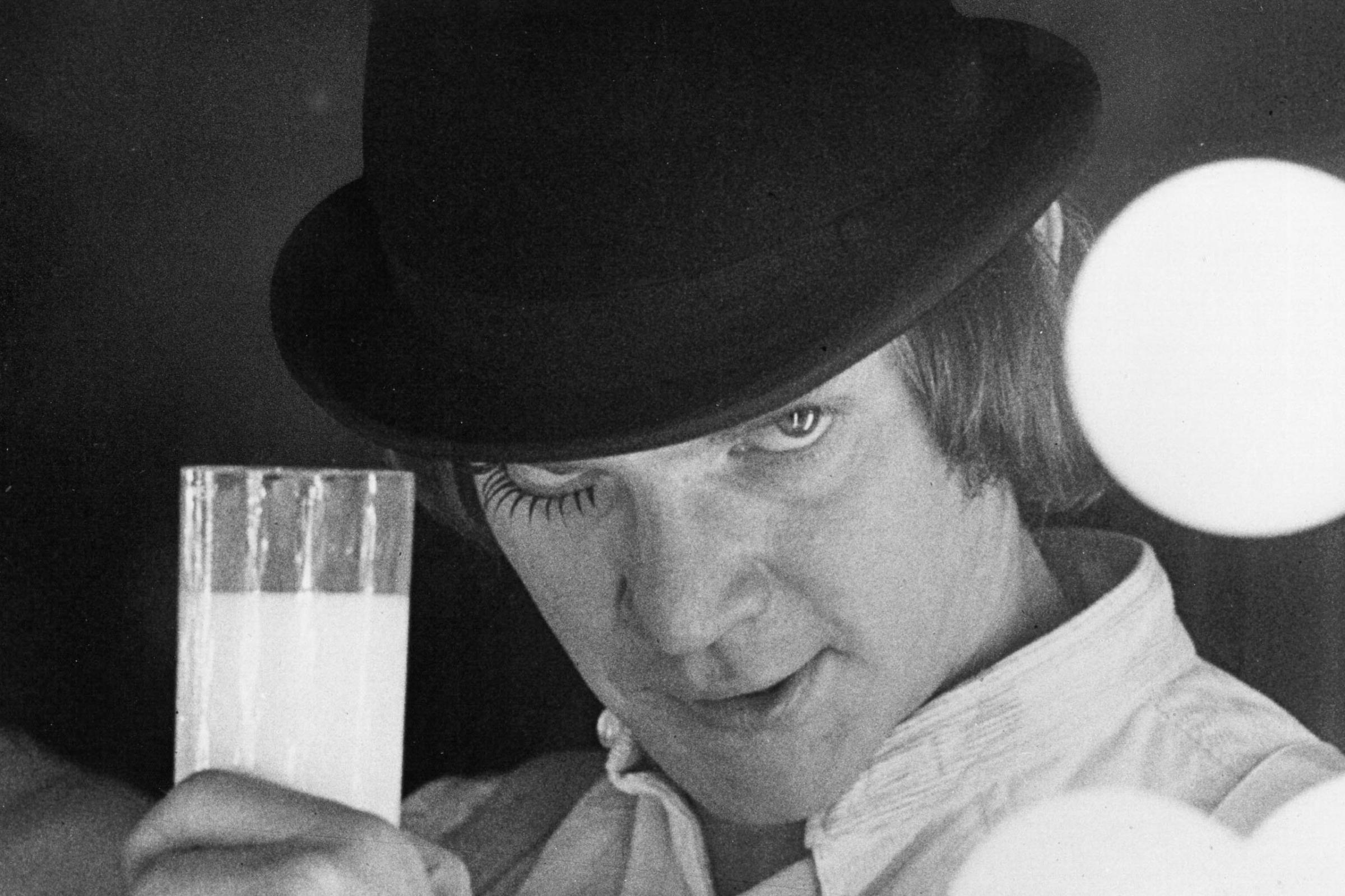

That’s the million-dollar question. For a few reasons, suspicion has zeroed in on the North Korean government or a band of allied hacktivists. The hermit kingdom is apoplectic over The Interview, in which Seth Rogen and James Franco play journalists who land a face-to-face with Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un, only to be asked by the CIA to assassinate the reclusive leader. The comedy features graphic footage of the dictator’s death, which didn’t go over well in a country built on a hereditary personality cult.

From a forensic perspective, the hack had hallmarks of North Korean influence. The attackers breached Sony’s network with malware that had been compiled on a Korean-language computer. And the effort bore similarities to attacks by a hacking group with suspected ties to North Korea that has carried out attacks on South Korean targets, including a breach of South Korean banks in 2013. That group, which is alternately known in the cybersecurity community as DarkSeoul (after its frequent target) or Silent Chollima (after a mythical winged horse), often uses spear-phishing—a cyber-attack that targets a specific vulnerable user or department on a larger network.

MORE: U.S. sees North Korea as culprit in Sony attack

That does not necessarily mean the North Korean government, or even the same hacker collective, is responsible. In the world of cyberwarfare, hackers will often dissect and imitate successful techniques.

Even the clues that point toward Pyongyang could be diversions to deflect investigators. For example, the perpetrators could’ve manipulated the code or set the computer language to throw suspicion on a convenient culprit. Pyongyang has denied involvement.

Why did Sony scrub The Interview?

People who may or may not have been tied to the hackers posted a vague message Tuesday threatening 9/11-style attacks against theaters that chose to play the film. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security said there wasn’t any evidence of a credible threat against American movie theaters, but several major chains, including AMC and Regal, decided to play it safe—all told, chains that control about half of the country’s movie screens decided against playing The Interview. Sony then followed suit, pulling the movie entirely.

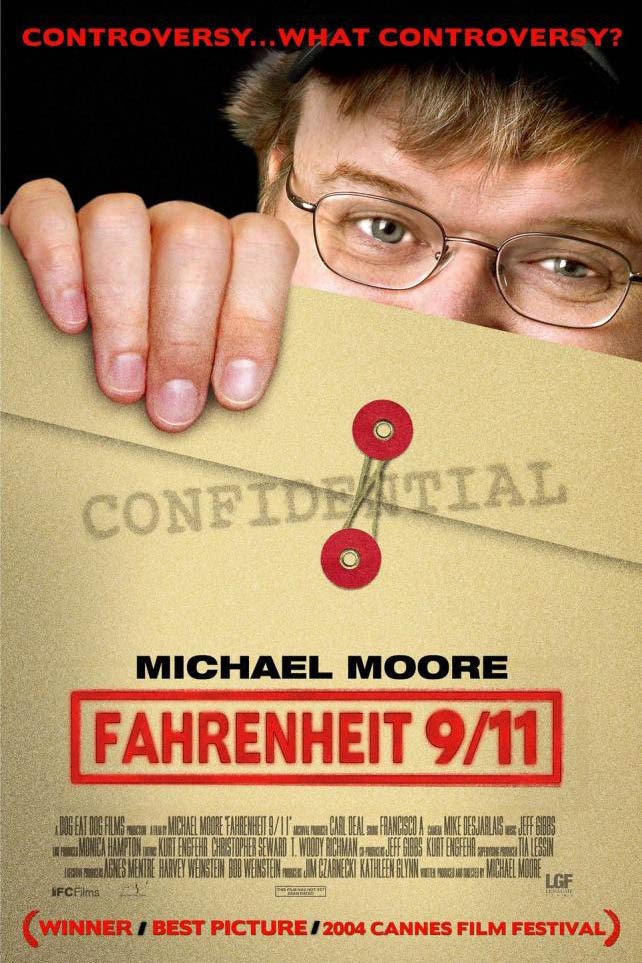

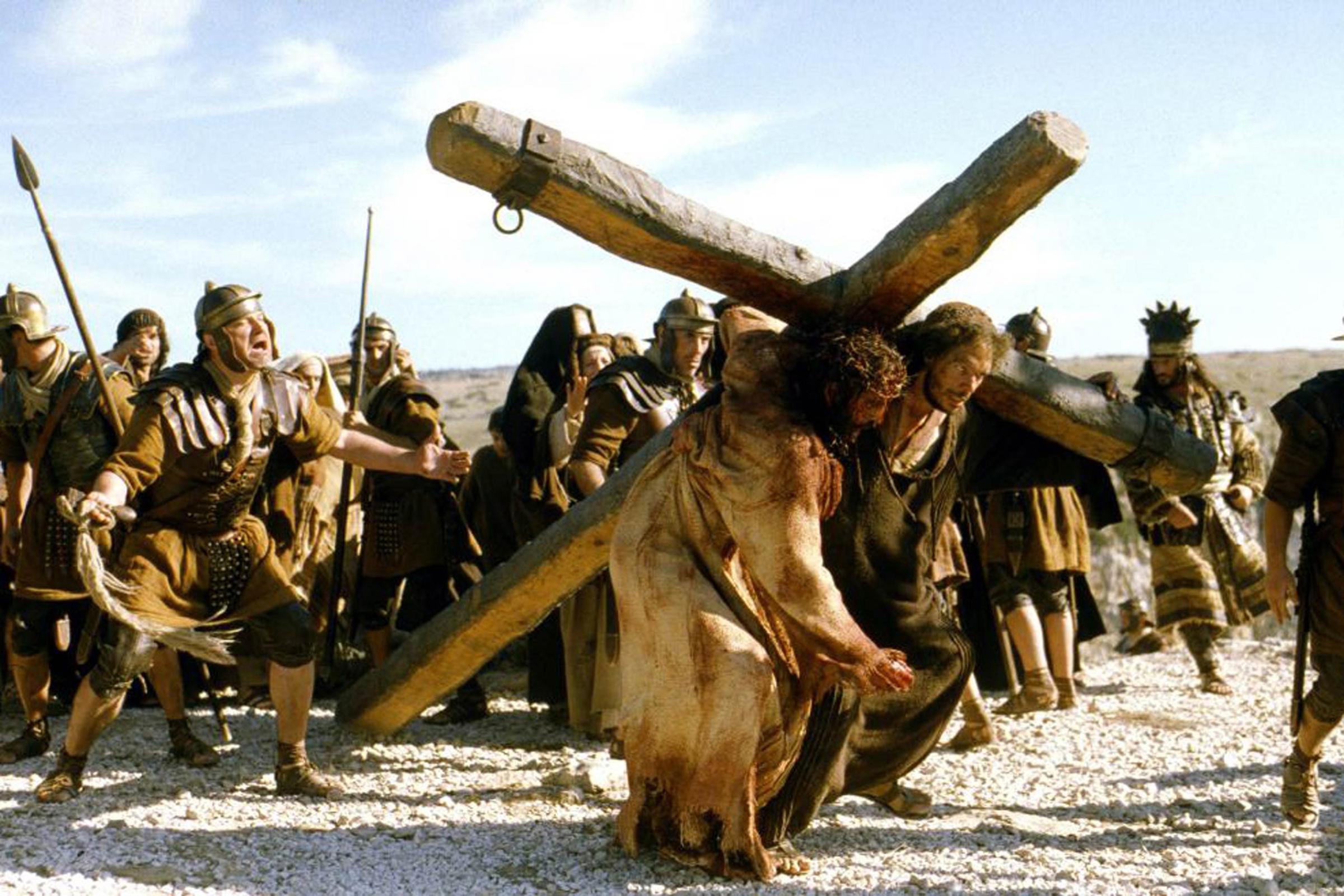

The Most Controversial Films of All Time

Were theaters really in danger?

It’s tough to say for sure. North Korea has made lots of bloviating threats toward the U.S. before, so anything that comes out of Pyongyang should be taken with a grain of salt. But again, no concrete proof has been made public yet that these attacks or the threat came from North Korea—or even that they came from the same person or group.

Will we ever get to see The Interview?

Probably. The movie cost about $44 million to make, according to documents leaked by the hackers. The ad campaign so far has cost tens of millions on top of that, although Sony has pulled the plug on further TV spots. A total loss on that investment would be a tough pill for Sony to swallow.

MORE: You can’t see The Interview, but TIME’s movie critic did

What will most likely happen is some limited release in the future when everything calms down, perhaps bypassing theaters and going right to Blu-Ray/DVD and on-demand services. There’s also a chance Sony could release the film online. That would eliminate pretty much any safety risk to viewers, but could further enrage whoever hacked Sony—assuming they actually care about The Interview and it’s not just a red herring. It would also let Sony capitalize on all the sudden interest in the film generated by the hack and threats. Don’t expect to see it soon: Sony said late Wednesday it’s not planning any kind of release. But it could, of course, be leaked online.

In an interview with ABC News on Wednesday, President Barack Obama called the hack against Sony “very serious,” but suggested authorities have yet to find any credibility in the threat of attacks against theaters.

“For now, my recommendation would be that people go to the movies,” Obama said.

How did the hackers do it?

We don’t know exactly. Cyber-security experts say the initial breach could have occurred through a simple phishing or spearfishing attempt, in which the hackers find a soft spot in the company’s network defenses. That can be a coding error or an employee who clicks on an infected link. These breaches occur all the time. FireEye, the parent company of the cybersecurity firm Sony hired to probe the hack, studied the network security of more than 1,200 banks, government agencies and manufacturers over a six-month period ending in 2014, and found that 97% had their last line of defense breached at some point by hackers.

“Breaches are inevitable,” says Dmitri Alperovitch, co-founder of the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike. “But that just means they’ve gotten in the door. It doesn’t mean they’ll be able to walk out with the crown jewels or set fire to the building.”

Once inside, hackers will try to gain elevated security privileges to spread across the network. What made the Sony hack different was the fact that it wasn’t detected until large quantities of data had been swiped. And what stood out, several analysts say, was not the sophistication of the breach but the havoc the culprits sought to wreak. “The attack was very targeted, very well thought out,” says Mike Fey of the network-security firm Blue Coat Systems, who believes the hackers “planned and orchestrated” the attack for months.

What are investigators doing to find out who’s responsible?

Sony has brought in experts at Mandiant, a top security firm, to lead the probe of the hack. Their investigation, outside security experts say, will be similar in some ways to the forensic analysis that follow a murder: studying data logs, reviewing network communications, poring over code, matching clues to potential motives. It may involve probing bulletin boards on the Dark Web, where hackers sometimes go to seek advice on technical troubles.

“There’s a lot of detective work you can do,” says former Department of Justice cybercrime prosecutor Mark Rasch. “Are they native English speakers? What programming language do they use? The code will have styles, signatures and tells.”

And investigators are tracking the IP addresses from which the attack was launched, which in the case of the Sony hack included infected computers in locations ranging from Thailand to Italy.

What happens if it was North Korea?

It’s tough to say. It’s unprecedented for a state actor to conduct a cyberattack of this scale against a U.S. corporation. If that turns out to be the case, however the U.S. decides to respond will set the tone for a whole new kind of cyberwar.

Could the Sony hack happen to other companies?

It’s increasingly likely. Sony is unusual in large part because the attackers appear to have been driven by a desire to cause destruction, rather than financial motives. And the strange geopolitical overtones of the hack add a dollop of intrigue. “It’s a milestone because it’s such a large-scale destructive attack that is rooted in this bizarre political messaging,” says security researcher Kurt Baumgartner of Kaspersky Lab.

But cyber-warfare is a growing threat for which most companies are ill-prepared. Joseph Demarest, assistant director in the FBI’s cyber division, testified to a Senate panel earlier this month that the malware used in the Sony hack “probably [would have] gotten past 90% of the net defenses that are out there today in private industry.” Banks and government agencies tend to have better security, but in recent months major retailers like Target and Home Depot have been hit. When targeted by competent and persistent hackers, corporate defenses will often be outmatched. “This is a great wakeup call,” says Kevin Haley, a director at Symantec Security Response. “We need to get better at securing our organizations.”

-Additional reporting by Sam Frizell

Read next: You Can’t See ‘The Interview,’ but I Did

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com