[Note: This gallery contains graphic images.]

Some photographs are so much of their time that, as years pass, they acquire an air of genuine authority—about an event, a person, a place—and even, perhaps, an air of inevitability. This is what it was like, these pictures seem to say. This is what happened. This is the moment. This is what we remember.

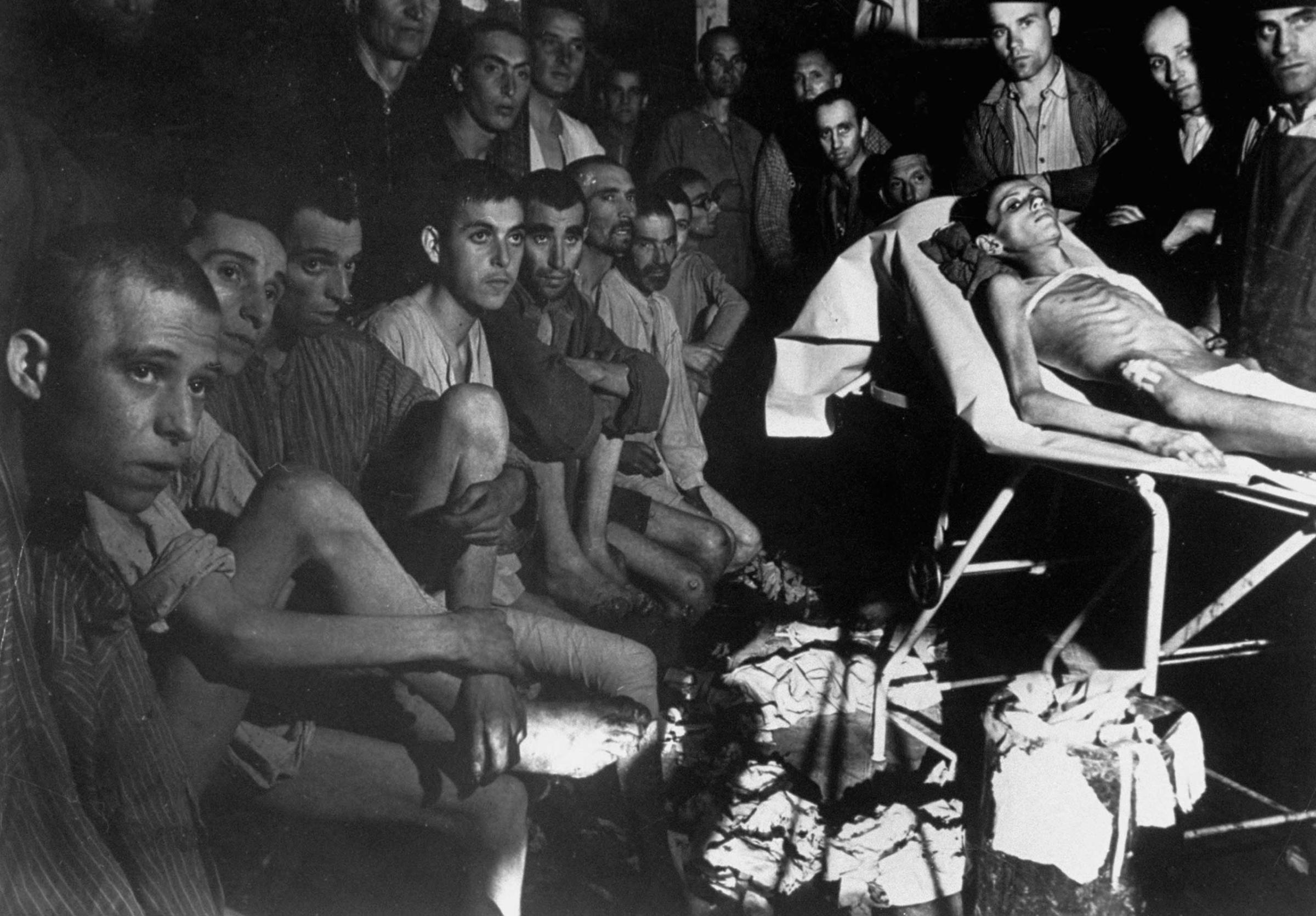

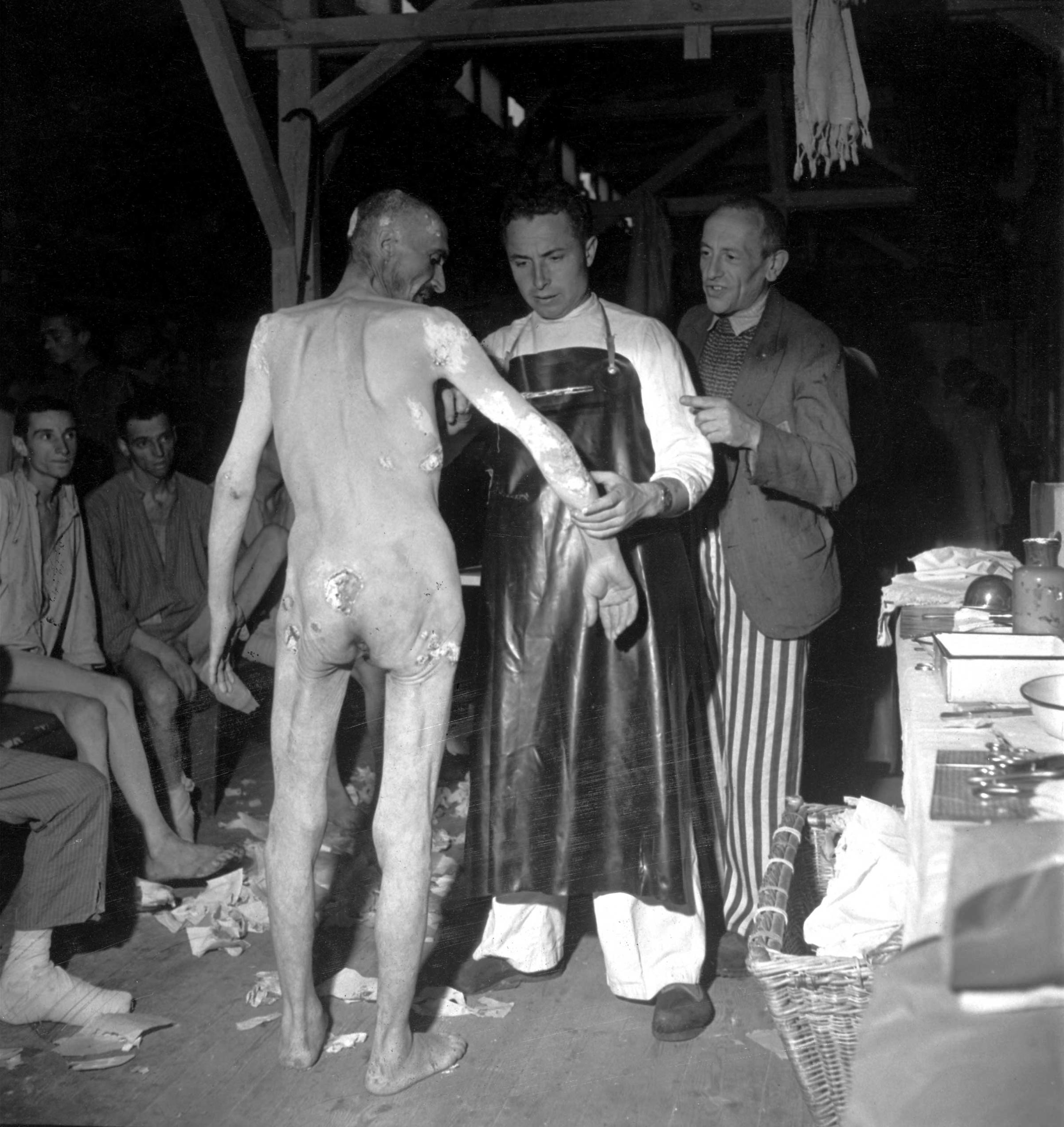

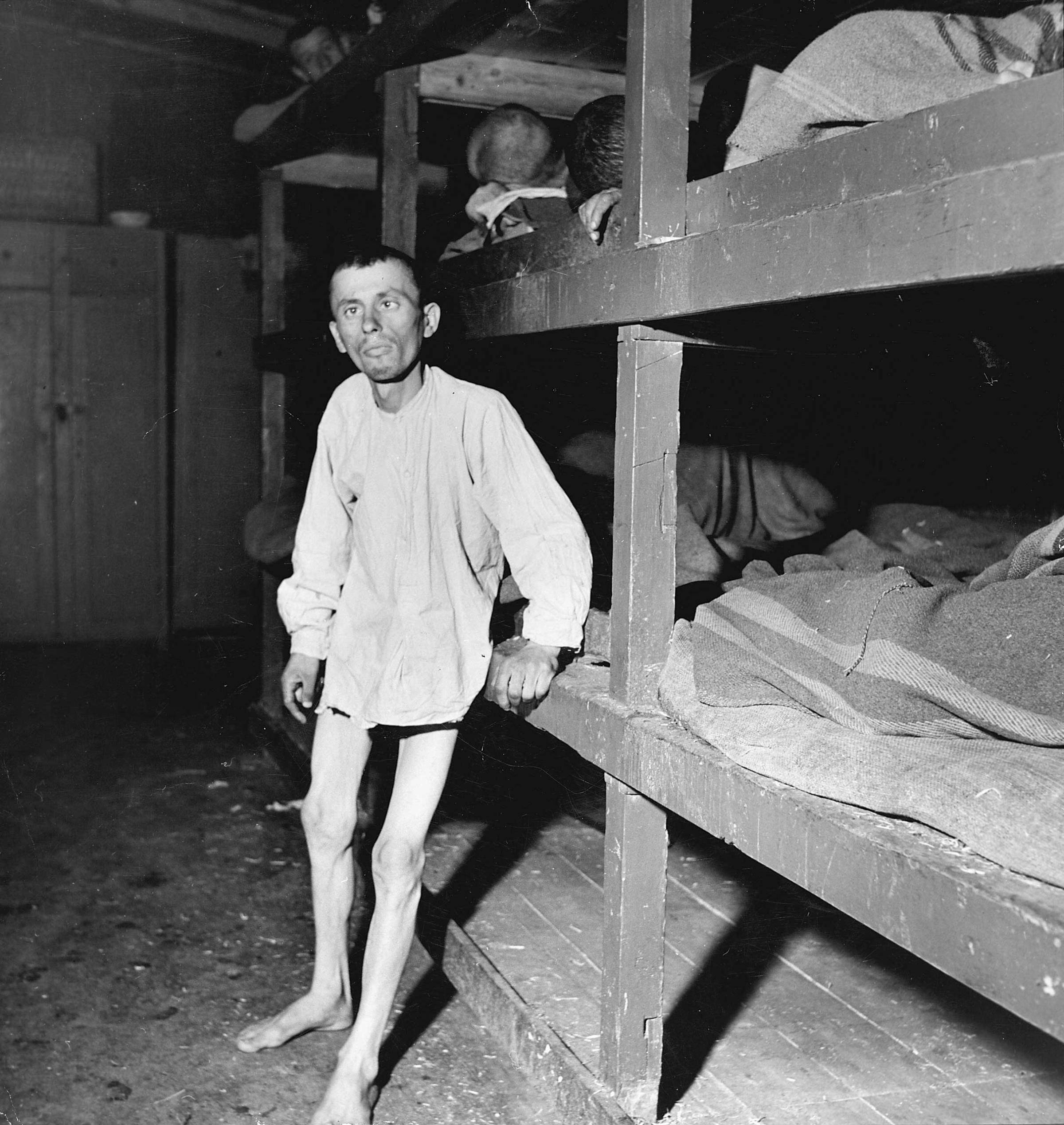

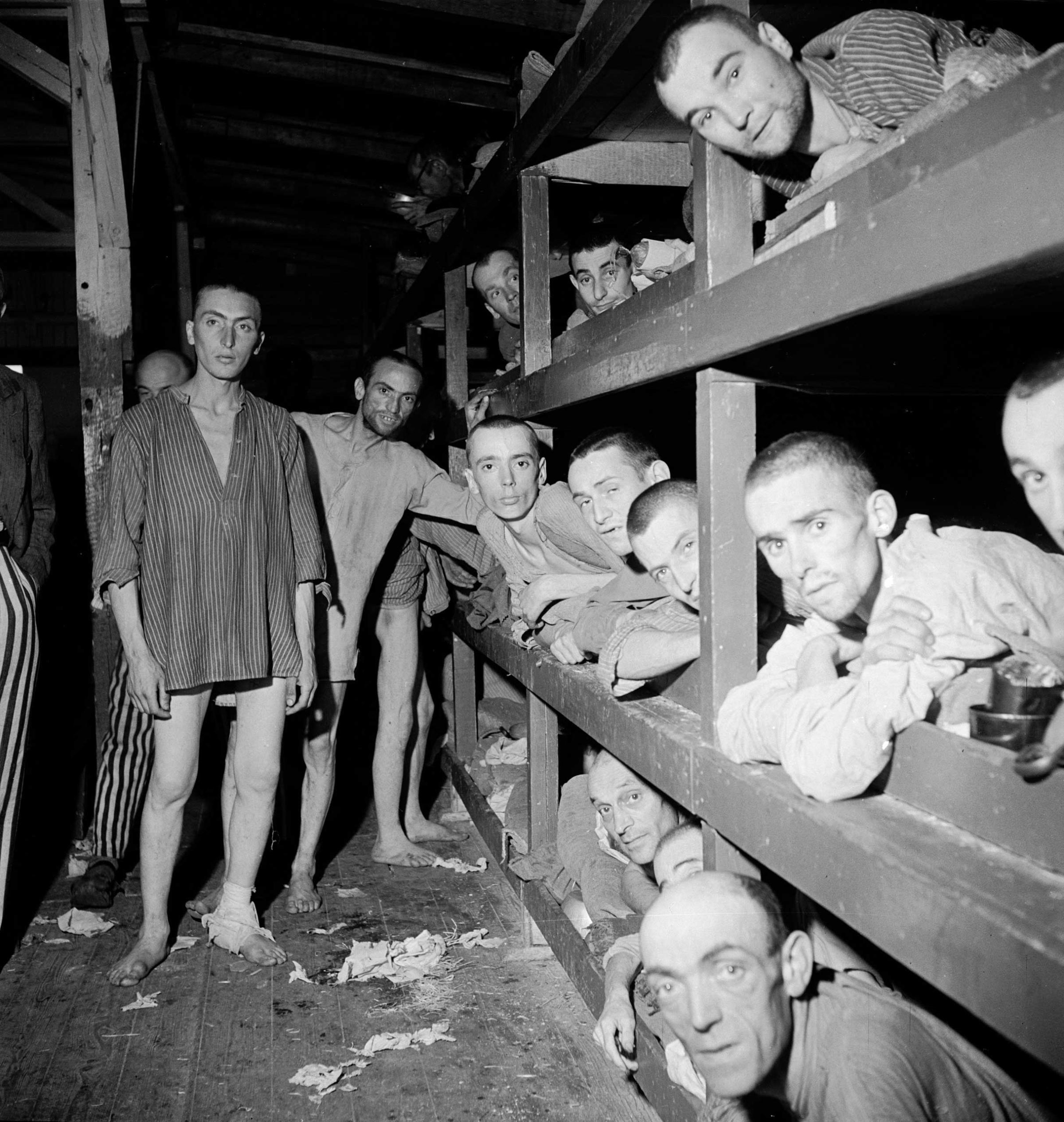

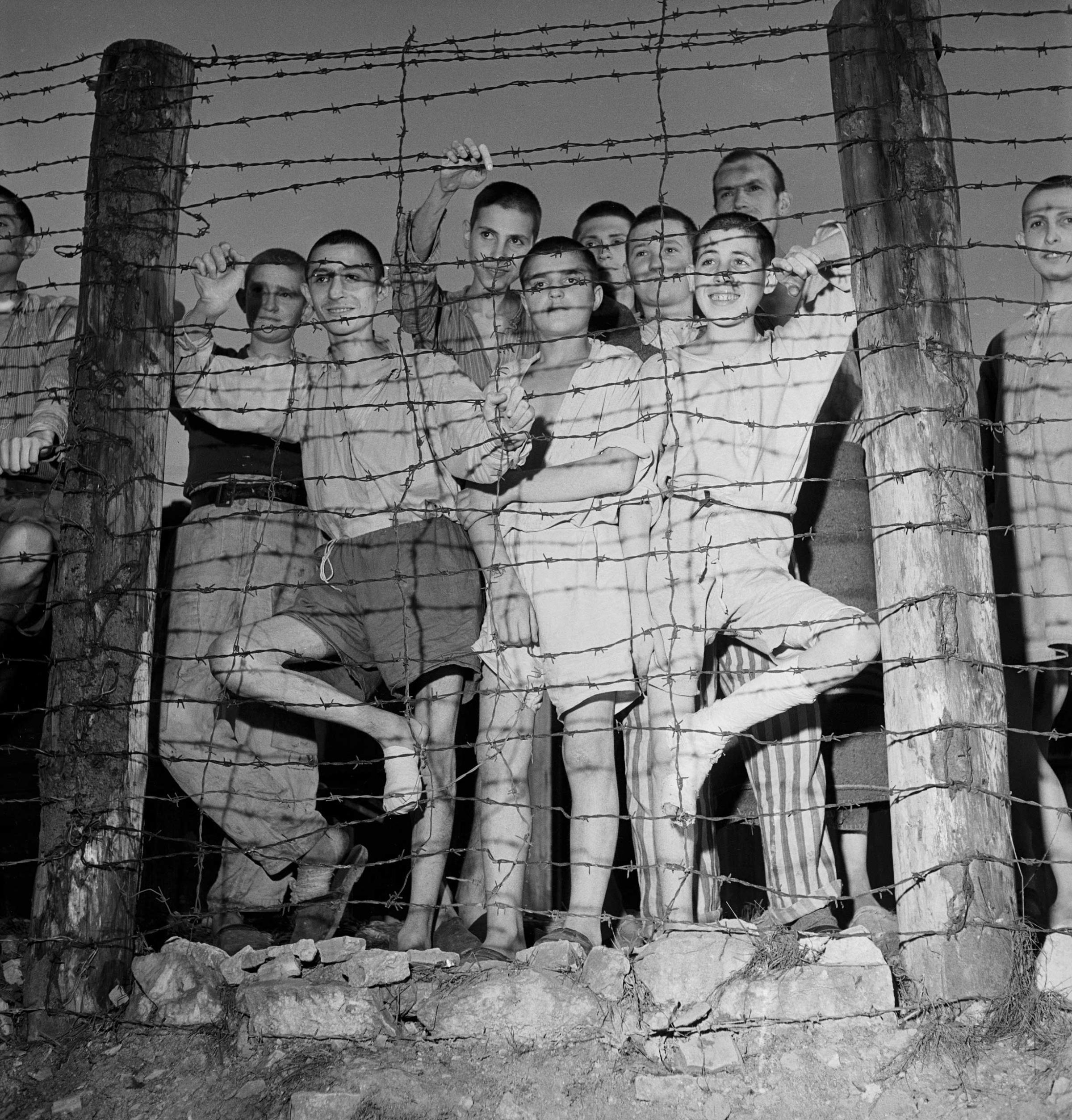

Of the many indispensable photos made during the Second World War, Margaret Bourke-White’s portrait of survivors at Buchenwald in April 1945—”staring out at their Allied rescuers,” as LIFE magazine put it, “like so many living corpses”—remains among the most haunting. The faces of the men, young and old, staring from behind the wire, “barely able to believe that they would be delivered from a Nazi camp where the only deliverance had been death,” attest with an awful eloquence to the depths of human depravity and, perhaps even more powerfully, to the measureless lineaments of human endurance.

What few people recall about Bourke-White’s survivors-at-the-wire image, however, is that it did not even appear in LIFE until 15 years after it was made, when it was published alongside other photographic touchstones in the magazine’s Dec. 26, 1960, special double-issue, “25 Years of LIFE.”

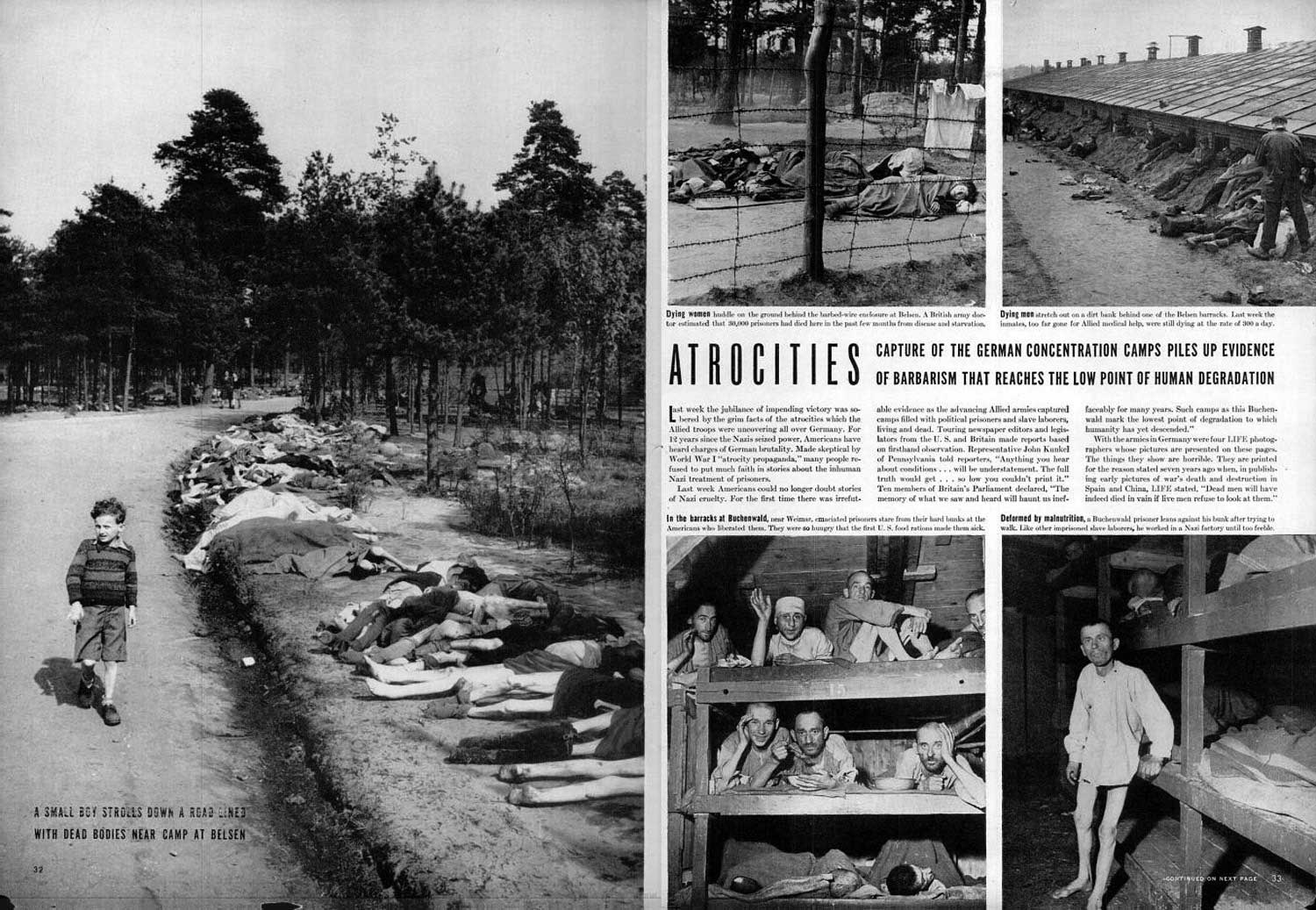

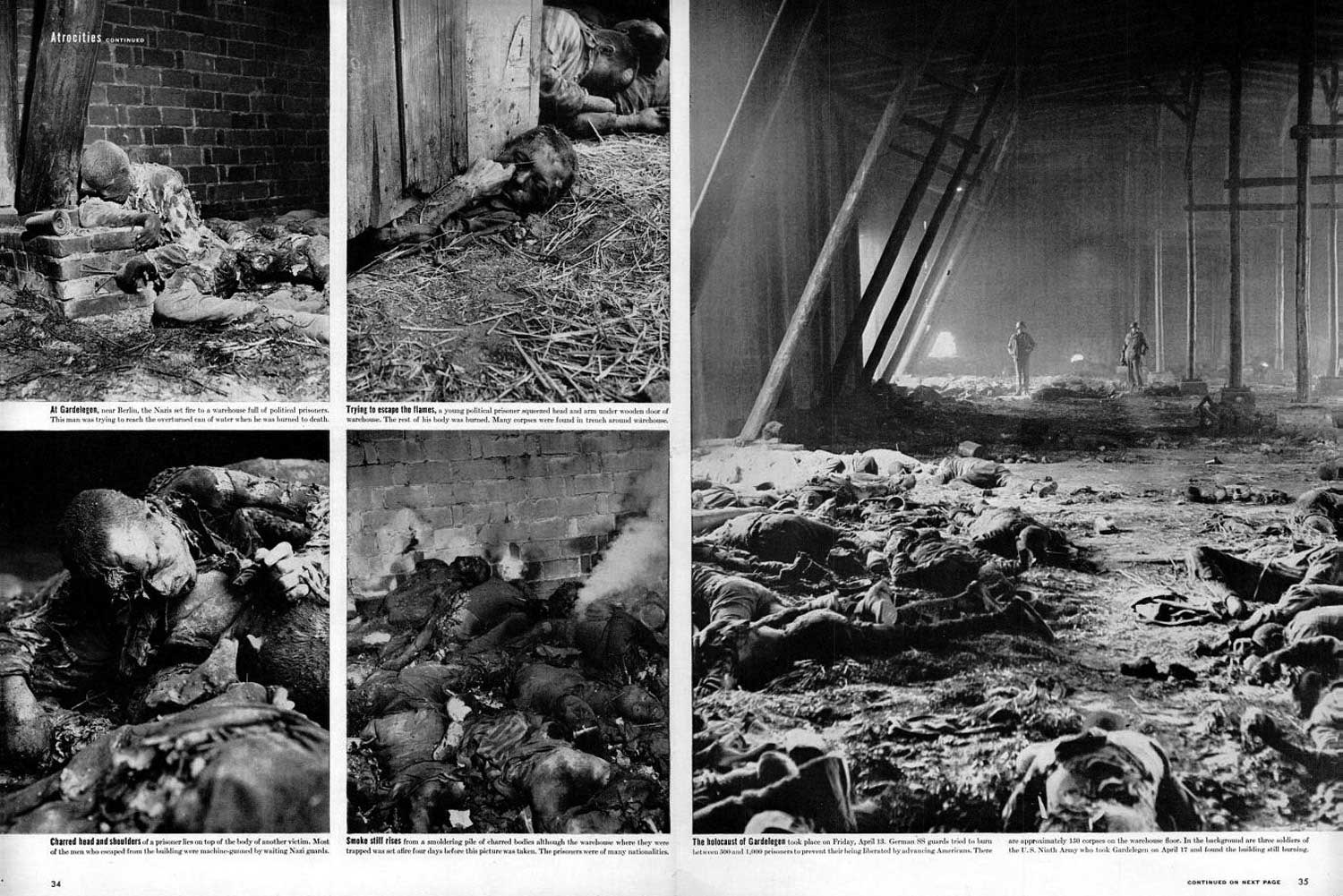

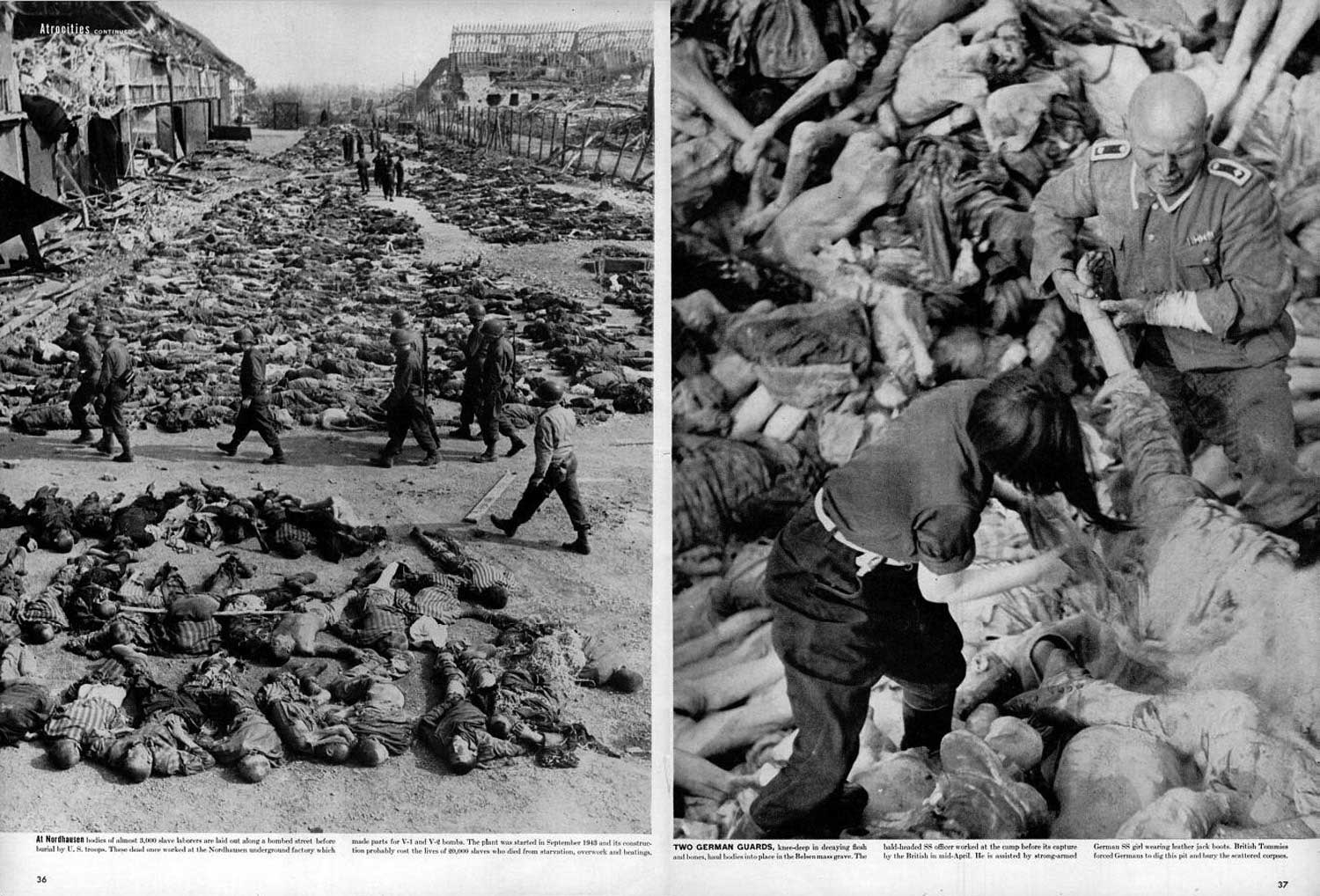

Pictures from Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and other camps that LIFE did publish—made when Bourke-White and her colleagues accompanied Gen. George Patton’s Third Army on its storied march through a collapsing Germany in the spring of 1945—were among the very first to document for a largely disbelieving public, in America and around the world, the wholly murderous nature of the camps. (At the end of this gallery, see how the original story on the liberation of the camps appeared in the May 7, 1945, issue of LIFE, when the magazine published a series of brutal photographs by Bourke-White, William Vandivert and other LIFE staffers.)

Here, eight decades after the liberation of Buchenwald, LIFE.com presents a series of Bourke-White photographs—most of which never ran in LIFE magazine—from that notorious camp located a mere five miles outside the ancient, picturesque town of Weimar, Germany.

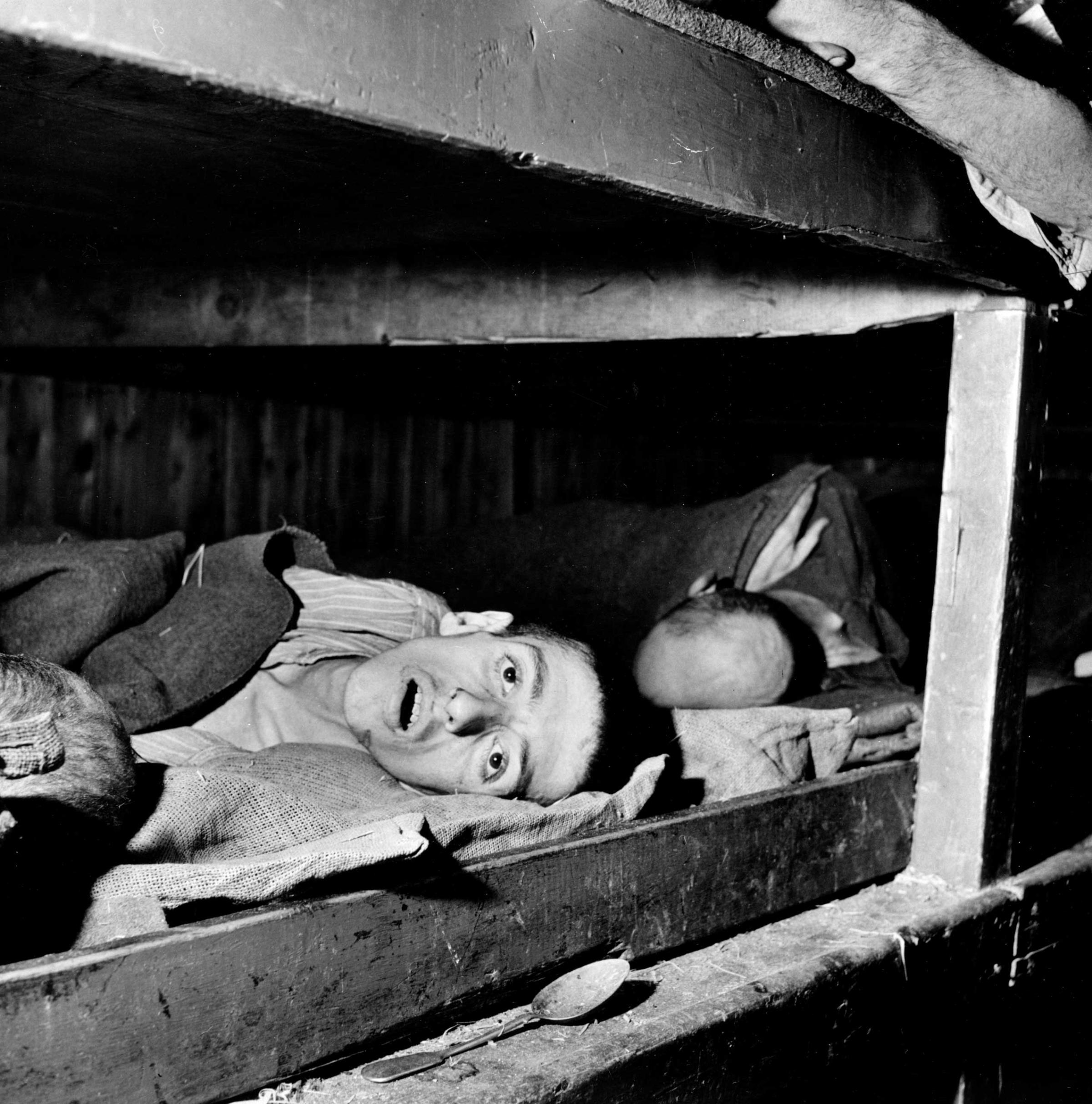

Her justifiably iconic picture of men at the Buchenwald fence suggests the horrors made manifest by the Nazi push for a “final solution”: the other Bourke-White photographs here, on the other hand, do not suggest, or hint at, the Third Reich’s horrors. Instead, they force the Holocaust’s nightmares into the unblinking light.

In Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly—her devastating 1946 memoir, subtitled “A Report on the Collapse of Hitler’s ‘Thousand Years'”—Bourke-White recalls the ghastly landscape that confronted the Allied troops who liberated Buchenwald, and her own tortured response to what she, the Allied troops and her fellow journalists witnessed and recorded there:

There was an air of unreality about that April day in Weimar, a feeling to which I found myself stubbornly clinging. I kept telling myself that I would believe the indescribably horrible sight in the courtyard before me only when I had a chance to look at my own photographs. Using the camera was almost a relief; it interposed a slight barrier between myself and the white horror in front of me.

This whiteness had the fragile translucence of snow, and I wished that under the bright April sun which shone from a clean blue sky it would all simply melt away. I longed for it to disappear, because while it was there I was reminded that men actually had done this thing—men with arms and legs and eyes and hearts not so very unlike our own. And it made me ashamed to be a member of the human race.

The several hundred other spectators who filed through the Buchenwald courtyard on that sunny April afternoon were equally unwilling to admit association with the human beings who had perpetrated these horrors. But their reluctance had a certain tinge of self-interest; for these were the citizens of Weimar, eager to plead their ignorance of the outrages.

In one of the signal moments of his long career and, indeed, of the entire war, an enraged General Patton refused to recognize that the Weimar citizens’ ignorance might be genuine—or, if it was genuine, that it was somehow, in any moral sense, pardonable. He ordered the townspeople to bear witness to what their countrymen had done, and what they themselves had allowed to be done, in their name.

Margaret Bourke-White’s pictures of these terribly ordinary men and women—appalled, frightened, ashamed amid the endless evidence of the terrors their compatriots had unleashed—remain among the most unsettling she, or any photographer, ever made. Long before the political theorist Hannah Arendt introduced her notion of the “banality of evil” to the world in her 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem, Margaret Bourke-White had already captured its face, for all time, in her photographs of “good Germans” forced to confront their own complicity in a barbarous age.

Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com