Ask any American today under the age of, say, 40, “Who was Gypsy Rose Lee?” and chances are pretty good that the reaction will be utter bewilderment. “Gypsy Rose who?”

On the other hand, ask anyone who came of age in the 1940s or ’50s the same question, and the reaction will likely be something along the lines of, “Gypsy Rose Lee? I haven’t thought about her in decades! But let me tell you, back in the day. . . .”

Gypsy Rose Lee (born Rose Louise Hovick in Seattle in 1911) was—and remains—a force in American popular culture not because she acted in films (although she did act in films) or because she wrote successful mystery novels (although she did write successful mystery novels). The reason Lee’s influence endures can be attributed to two central elements of her remarkable, all-American life story: first, her 1957 memoir, Gypsy, which formed the basis for what more than a few critics laud as the greatest of all American musicals, the 1959 Styne-Sondheim-Laurents masterpiece, Gypsy; and second, her career in burlesque, when she became the most famous—and perhaps the most singularly likable—stripper in the world. (Today’s “neo-burlesque” performers, like Dita Von Teese, Angie Pontani and others, cite Gypsy in near-reverent terms as a pioneer and inspiration.)

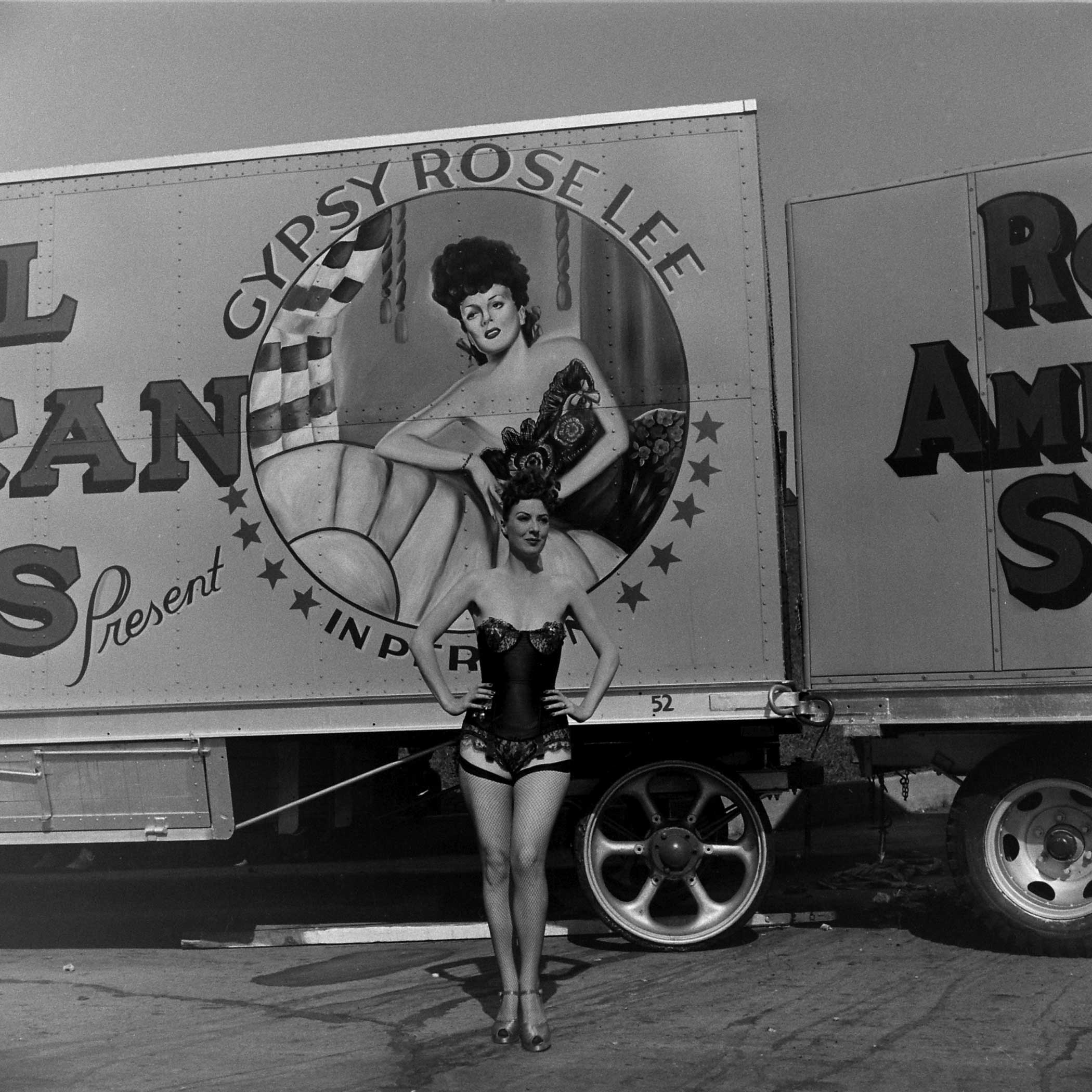

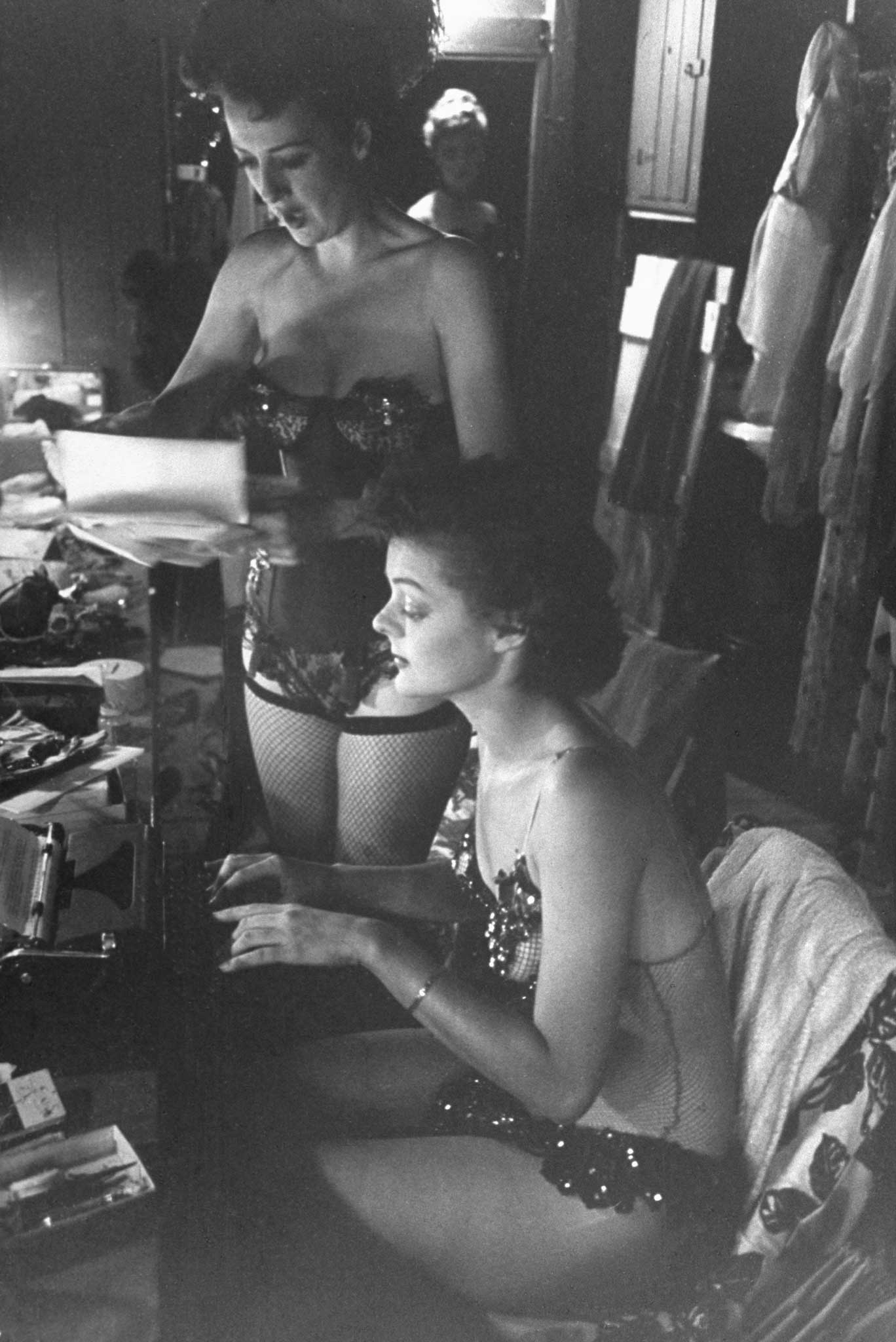

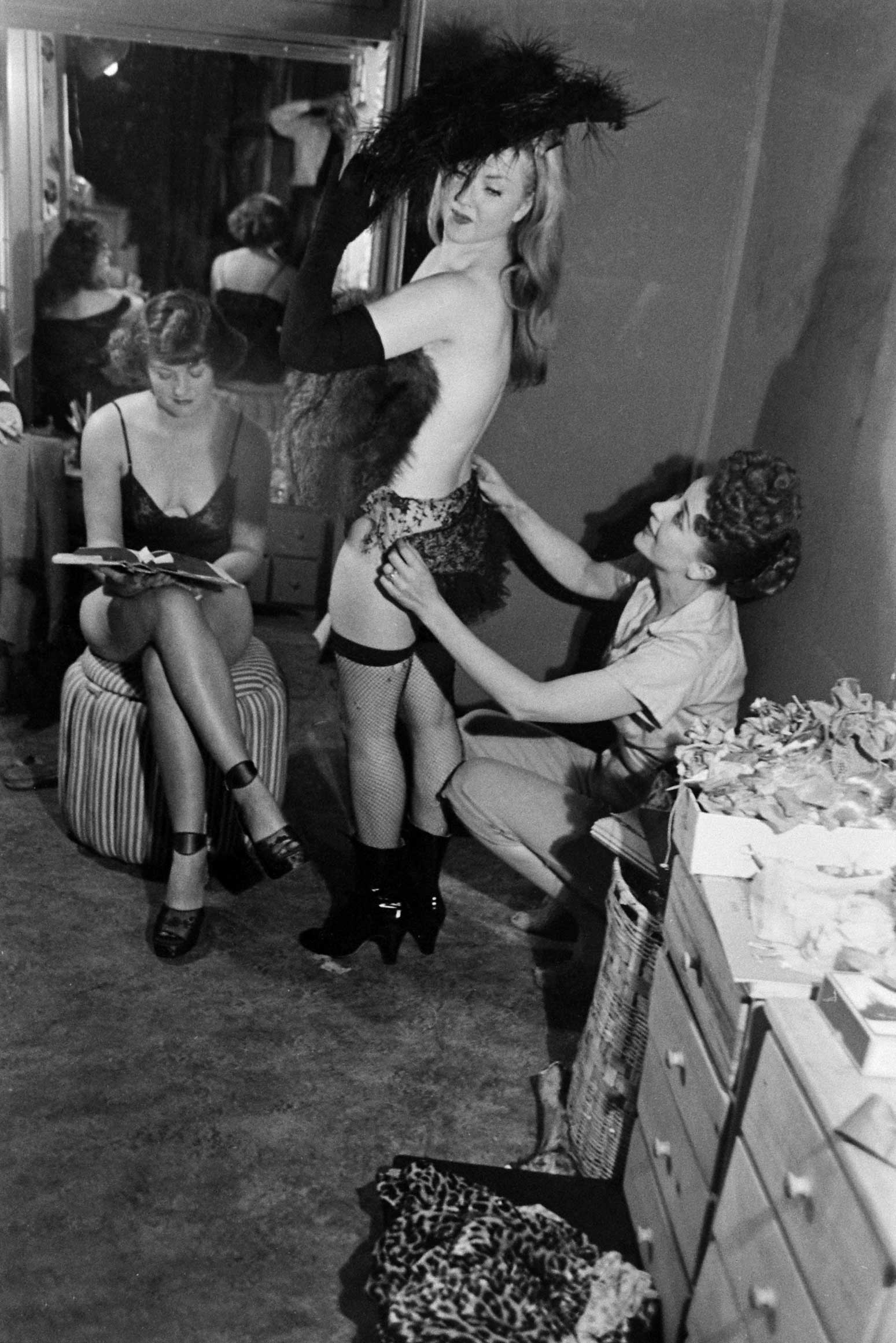

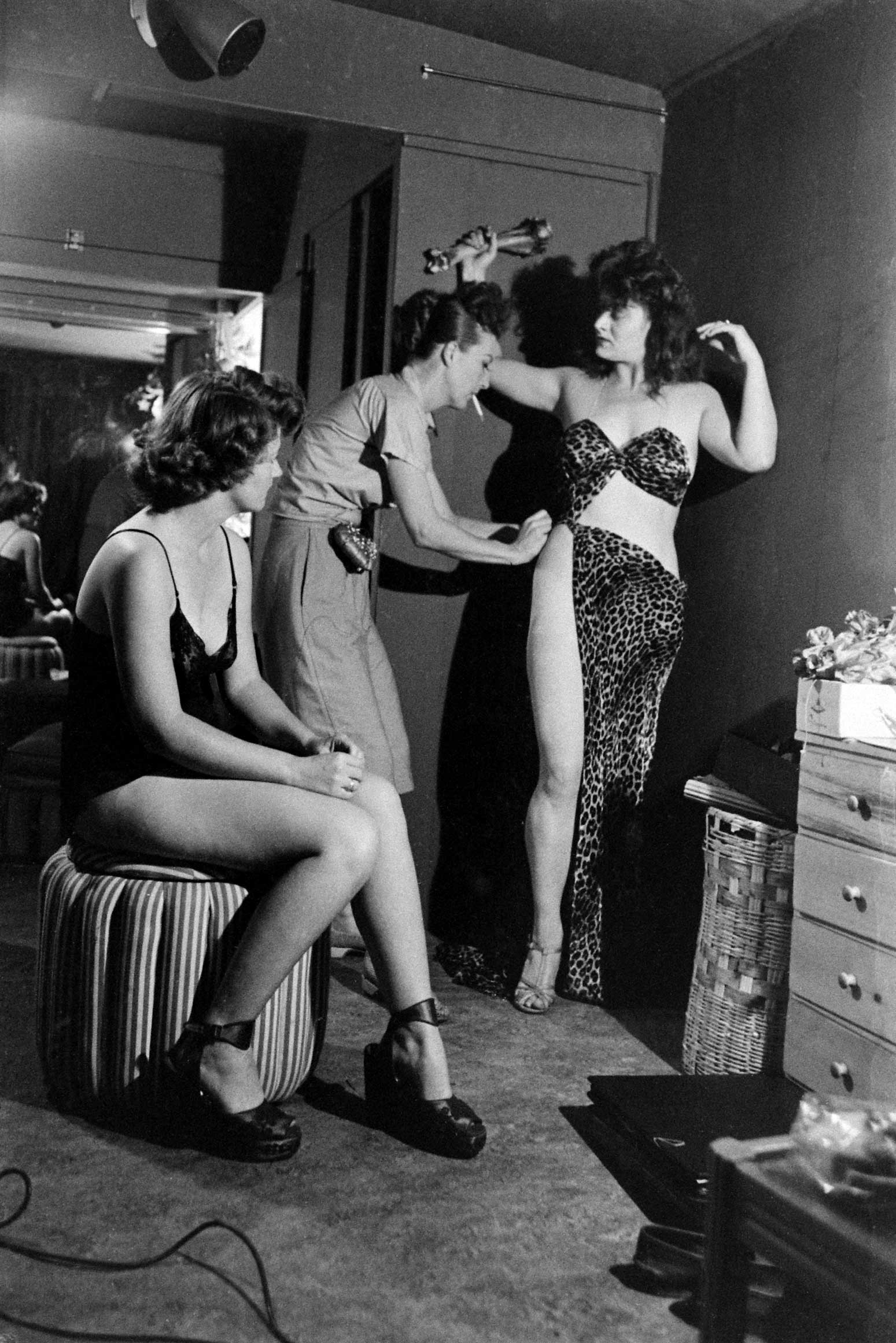

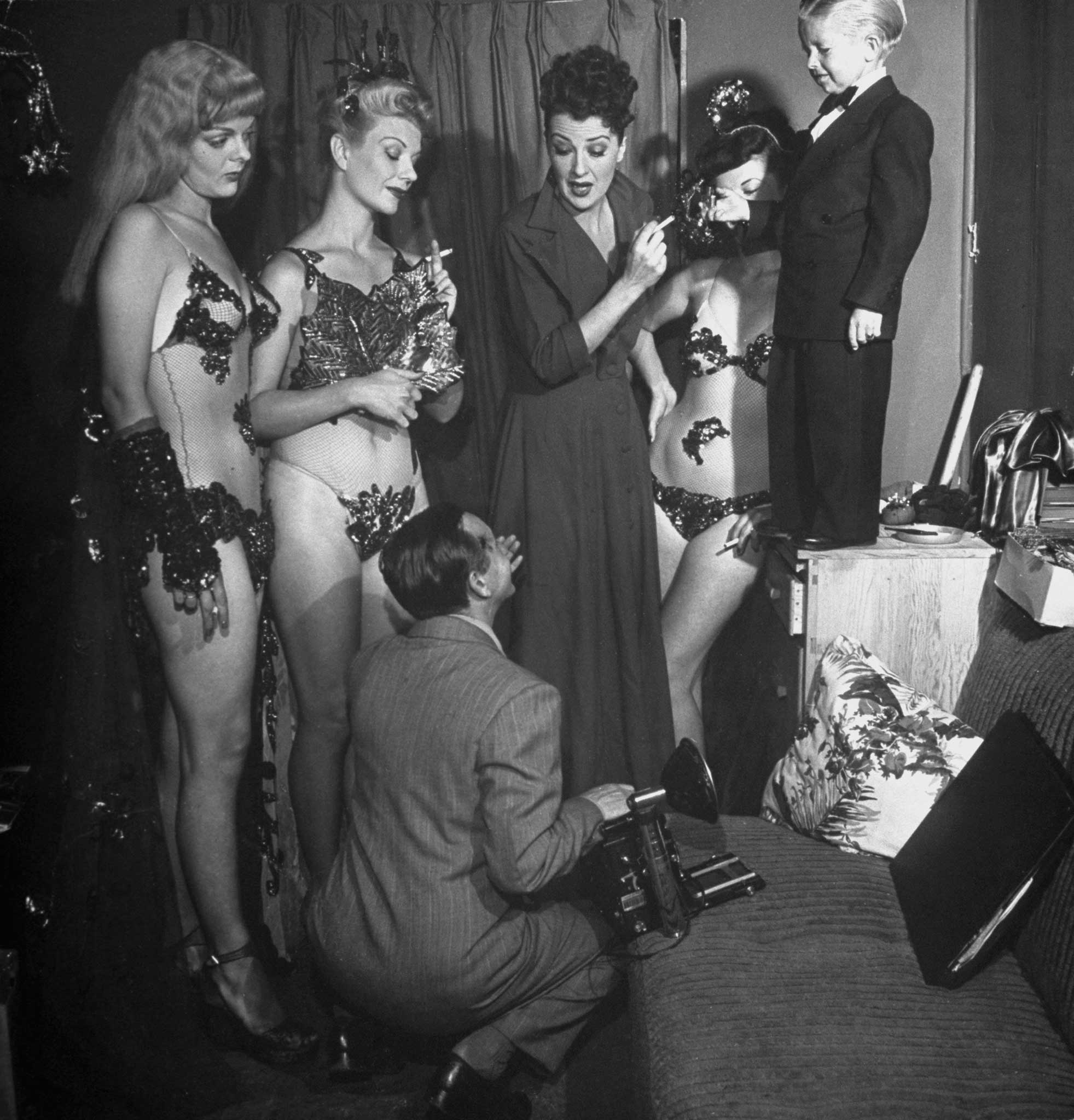

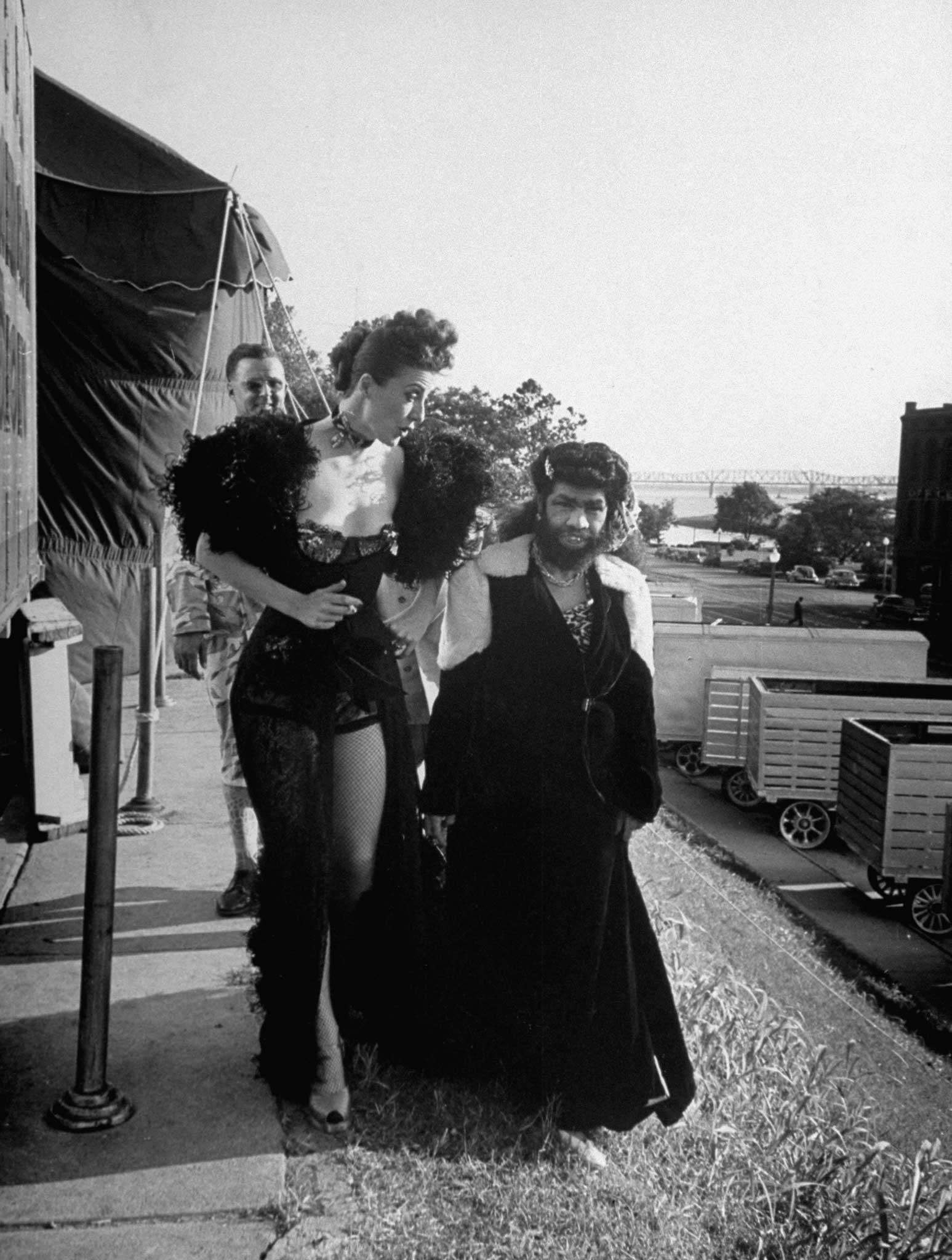

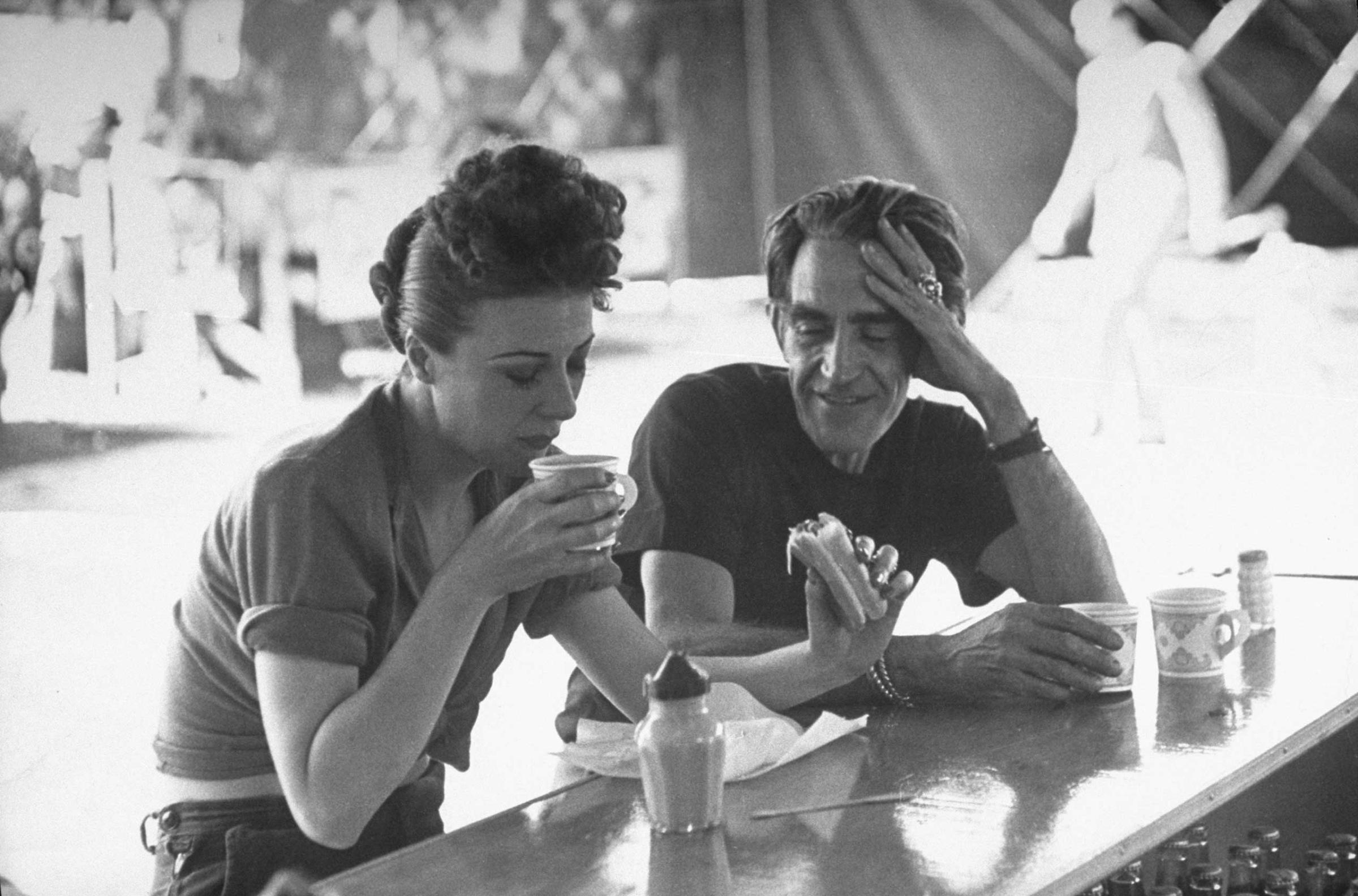

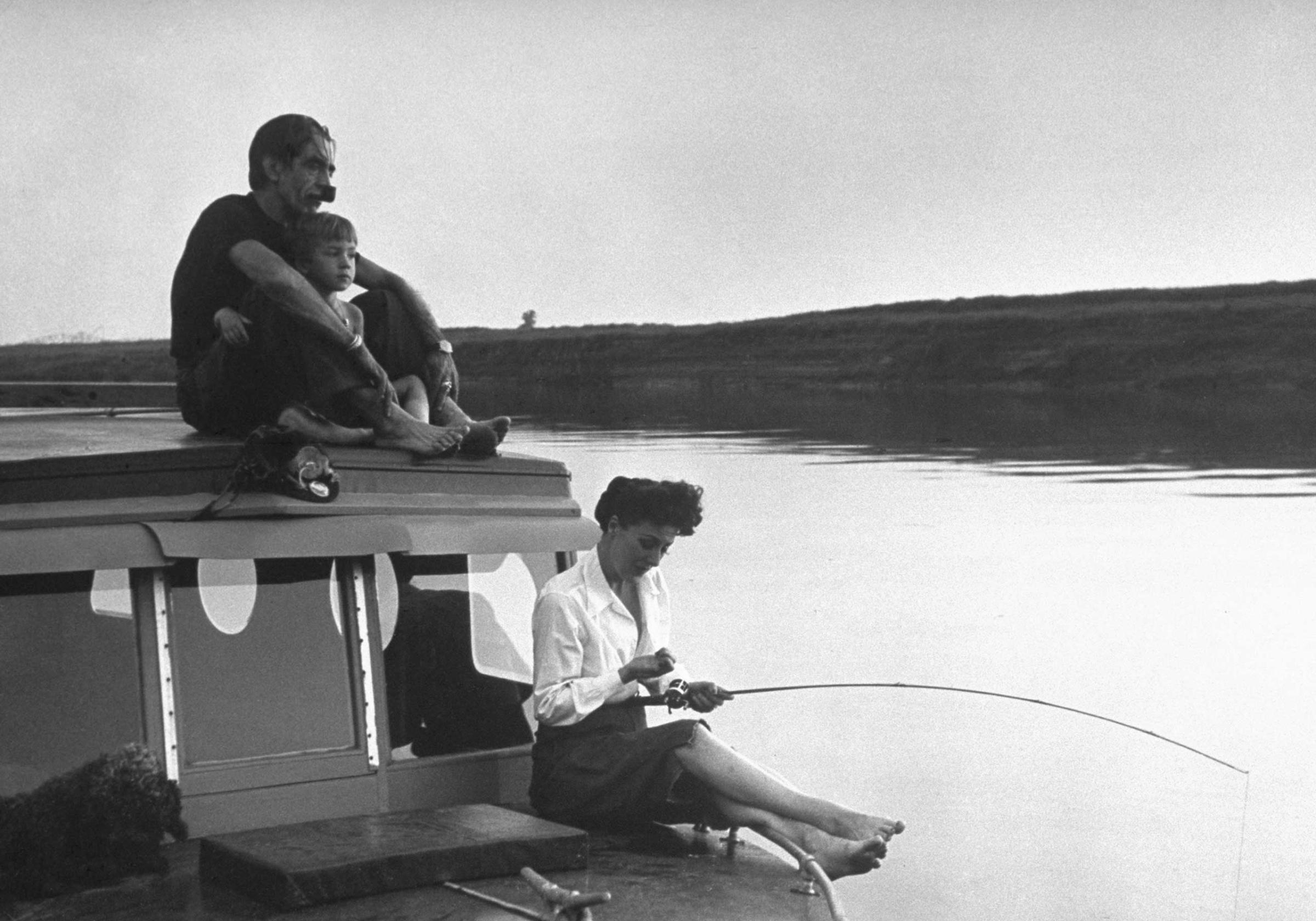

Here, LIFE.com celebrates Gypsy Rose Lee’s life and her career with a selection of pictures by George Skadding, a LIFE staffer far better known for photographing presidents (he was long an officer of the White House News Photographers Association) than burlesque stars. But, as the images in this gallery attest, Gypsy was hardly just another stripper; instead, as a performer, a wife and a mother of a young son, she had something about her—an approachable, self-deprecating demeanor aligned with a quiet self-certainty—that any politician would envy.

“I’m probably the highest paid outdoor entertainer since Cleopatra,” she’s quoted as saying in the June 6, 1949 issue of LIFE, in which many of these pictures first appeared. “And I don’t have to stand for some of the stuff she had to.”

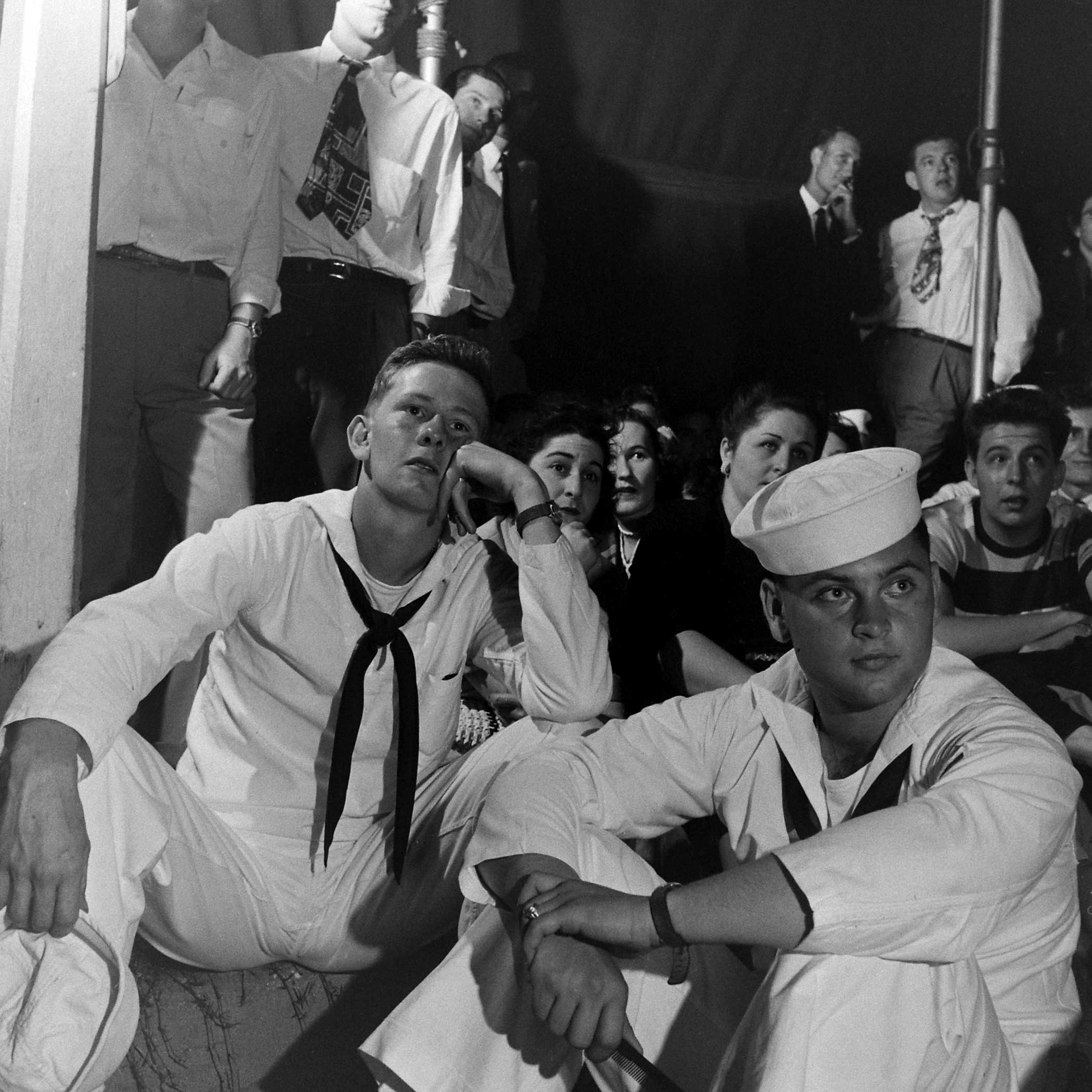

“Confidently taking her place among history’s great ladies, Gypsy has for the first time in her life gone outdoors professionally,” LIFE wrote at the beginning of Gypsy’s six-month tour with what was called “the world’s largest carnival,” The Royal American Shows. The prospect of having to do her old strip-tease act 8 to 15 times a day “all across the country to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan,” meanwhile—although hardly thrilling to the 38-year-old mom—was also something Gypsy could, characteristically, put in solid perspective:

“For $10,000 a week,” she told LIFE, “I can afford to climb the slave block once in a while.”

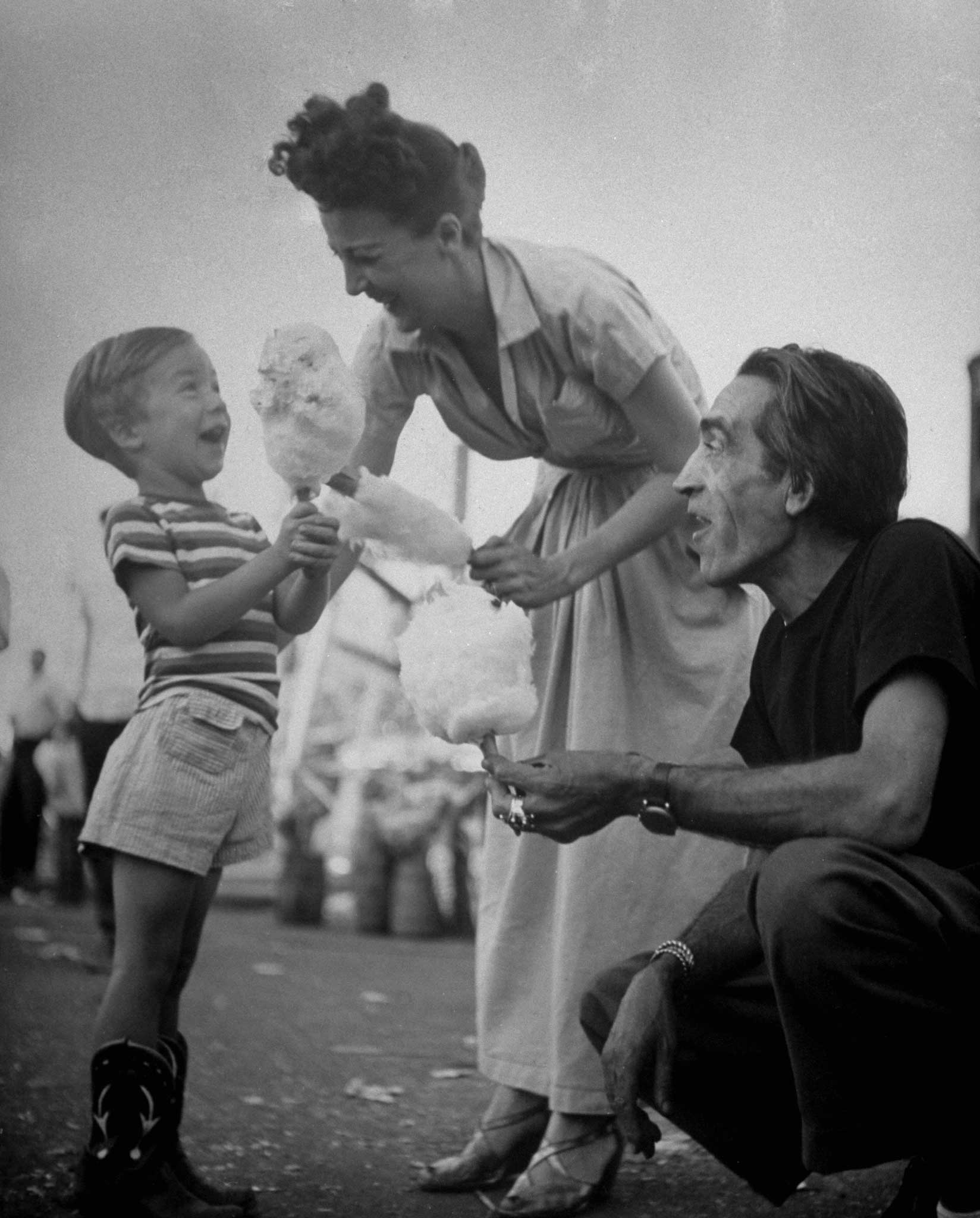

She also, as LIFE put it, “had it soft, as carny performers’ lives go. She lives in her own trailer with her third husband, the noted Spanish painter, Julio de Diego. With them is her 4-year-old son, Erik [Otto Preminger’s child, as it turned out] and his nurse. Gypsy, who loves to fish, carries an elaborate angler’s kit, and whenever the show plays near a river, goes out and hooks fish as ably as she does customers.”

But it’s in the notes of writer Arthur Shay, who spent a week with the star in Memphis, Tennessee, in May 1949, that we meet the woman who emerges when the lights go down and the crowds depart—and it’s clearly this Gypsy who truly connected to audiences wherever she went:

“Funny thing about show people—or just plain fans,” she told Shay at one point, offering insights into the appeal of her nomadic life. “They think if you’re not in Hollywood or on Broadway making a couple of thousand a week—taking guff from everybody and his cousin in the west, and sweating out poor crowds on Broadway—you’re not doing well. [But] I’ve been touring the country playing nightclubs and making twice as much as I made in the movies, and having more fun! I get a lot more fishing done, for one thing, and I can live in my trailer and see the country.”

Gypsy Rose Lee died in April, 1970, of lung cancer. She was just 59 years old.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com