It’s a rare picture that encompasses an era; even the most justly famous photographs seldom manage the feat. Eisenstaedt’s “V-J Day in Times Square,” for instance, perfectly illustrated the rapturous mood of a nation — and much of the world — at the end of the Second World War, but no one would argue that the image somehow captured the five-year war itself. Bill Eppridge’s haunting picture of Robert Kennedy’s assassination in a Los Angeles hotel kitchen in June 1968 distilled the darkest, most murderous currents of the Age of Aquarius, but no one says of that one photograph: “That was the Sixties.”

So, yes, it’s phenomenally rare for a single photo to evoke both a discrete moment, and an epoch. But that is exactly what Robert Capa’s now-iconic “Falling Soldier” manages to do; there, in one frame, in a picture made at the very moment a Loyalist fighter in Spain is shot and killed, one encounters a distillation of the Fascist violence — and the brutally extinguished Republican sense of hope for a new, free, egalitarian society — that ultimately came to define the Spanish Civil War.

[See more in the LIFE.com gallery, “The Best of LIFE: 37 Years in Pictures.”]

Before Capa’s falling soldier became Capa’s “Falling Soldier,” however — that is, before his picture acquired the patina of reverence, controversy (many people, after all, still believe the scene was staged) and downright myth that have accrued through the years — the photograph was, in fact, just that: a photograph in a magazine. Period.

As startling and dramatic as the picture was, and still is, it was not the cover image for the June 12, 1937, issue of LIFE. (That honor went to a close-up shot of “Grace the Dummy,” a Saks Fifth Avenue mannequin featured in a story on a new plaster concoction for store-window dummies, and a “keen young designer” who was topping those dummies “with heads resembling fashion editors.”)

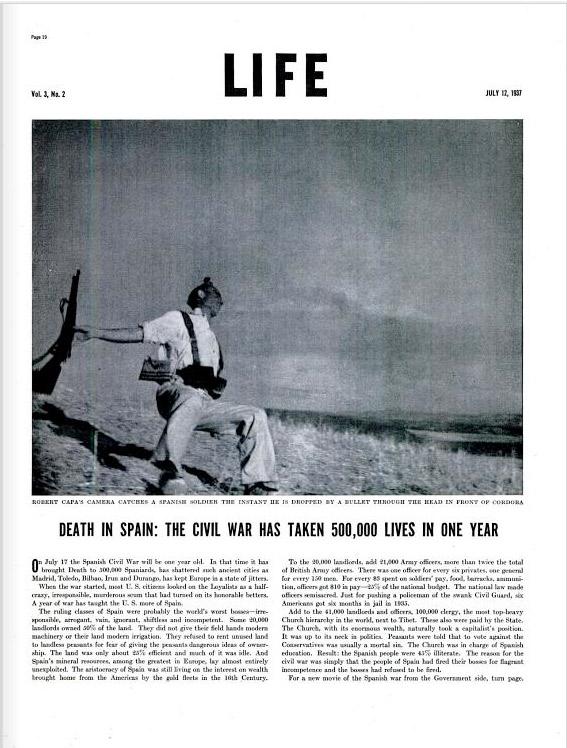

Nor was Capa’s picture even discussed in the article it accompanied. In fact, the only language devoted to the image itself can be found in the terse caption that ran beneath it:

ROBERT CAPA’S CAMERA CATCHES A SPANISH SOLDIER THE INSTANT HE IS DROPPED BY A BULLET THROUGH THE HEAD IN FRONT OF CORDOBA

Here, seven decades after the end of the Spanish Civil War, when Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s Nationalists conquered Madrid after a three-year siege, LIFE.com commemorates Capa’s photograph — not as an iconic visual document, but as a single picture, published three-quarters of a century ago on page 19 of a weekly magazine that, at the time, had not yet celebrated its first year in print.

After Capa’s photo appeared in LIFE, Franco went on to rule Spain for four decades — a dictator who overthrew a legitimate, elected government and not only survived, but thrived in the face of international complacency. Capa covered four more wars after Spain and died, killed by a landmine, camera in hand, in Southeast Asia in 1954.

Today, “Falling Soldier” is regarded as one of the 20th century’s indispensable photographs.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com