The miners didn’t hear the impact of the shell and kept extracting coal from the earth more than half a mile below the battlefield. They continued their work for several minutes, oblivious to the danger they were suddenly facing.

The shell, said to have been fired on Nov. 22 by the Ukrainian army in its war against pro-Russian separatists, had struck a shed at the state-owned Chelyuskintsev coal mine in the Petrovskyi district, located on the western edge of Donetsk in eastern Ukraine. The resulting explosion damaged the electrical and ventilation systems that serve the mine’s deepest shaft. A phone call from the security supervisor at the surface brought troubling news to the deputy director, who was working down below with more than 50 miners: they had just two hours of oxygen left, and the nearest elevator was now unpowered.

French photographer Jerome Sessini happened to be photographing at the mine that day. “At the beginning, the miners were quite relaxed and some of them were joking with us because it was a bit weird to see a photographer at the bottom of the mine,” Sessini told TIME. “The miners changed—their attitudes changed—so I felt something very serious was happening.” The deputy director reassured him that all was well, saying “don’t worry, everything is okay, just walk and everything will be fine.” (He wouldn’t find out until more than an hour later the kind of threat they had faced.)

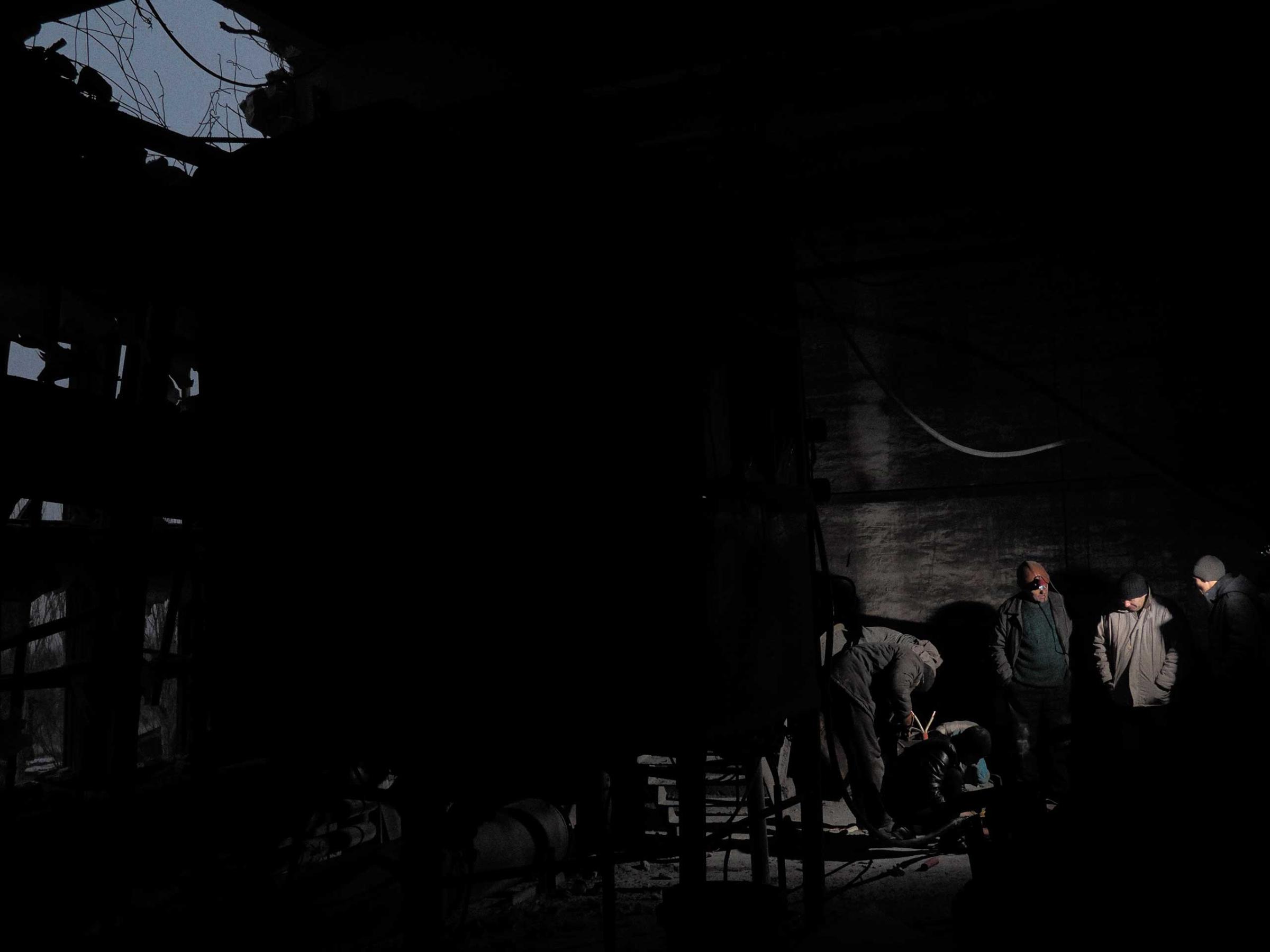

The men began to find their way up and out of the mine on foot, using their headlamps to light the way. Shadowed by Sessini, they walked for about 30 minutes until they reached a rusted cable car powered by a small rescue generator. The car took them along a railroad eight kilometers (five miles) away to an elevator that ran off a power source unaffected by the shelling. They were now 270 meters (885 feet) below ground level. The elevator hauled them to the top of the mine. An hour and 20 minutes after the shelling, the men reached daylight—safe from the threat underground but back into the war zone.

Since last spring, the Russia-backed separatists have fought government forces for control of the eastern region of the country, one of Ukraine’s main industrial hubs and its coal-mining heartland. At least 4,700 people have been killed in the fighting, the U.N. estimates, and more than half a million are internally displaced.

Based in Paris, Sessini has spent much of the past year covering the unrest and its civilian impact in Ukraine. From the pro-independence demonstrations in Kiev, which erupted after the country’s former president opted against signing an association deal with the European Union in favor of closer ties with Russia, to the rise of the separatist movements in Donetsk and Luhansk, he has intimately documented the country’s fracture into civil war.

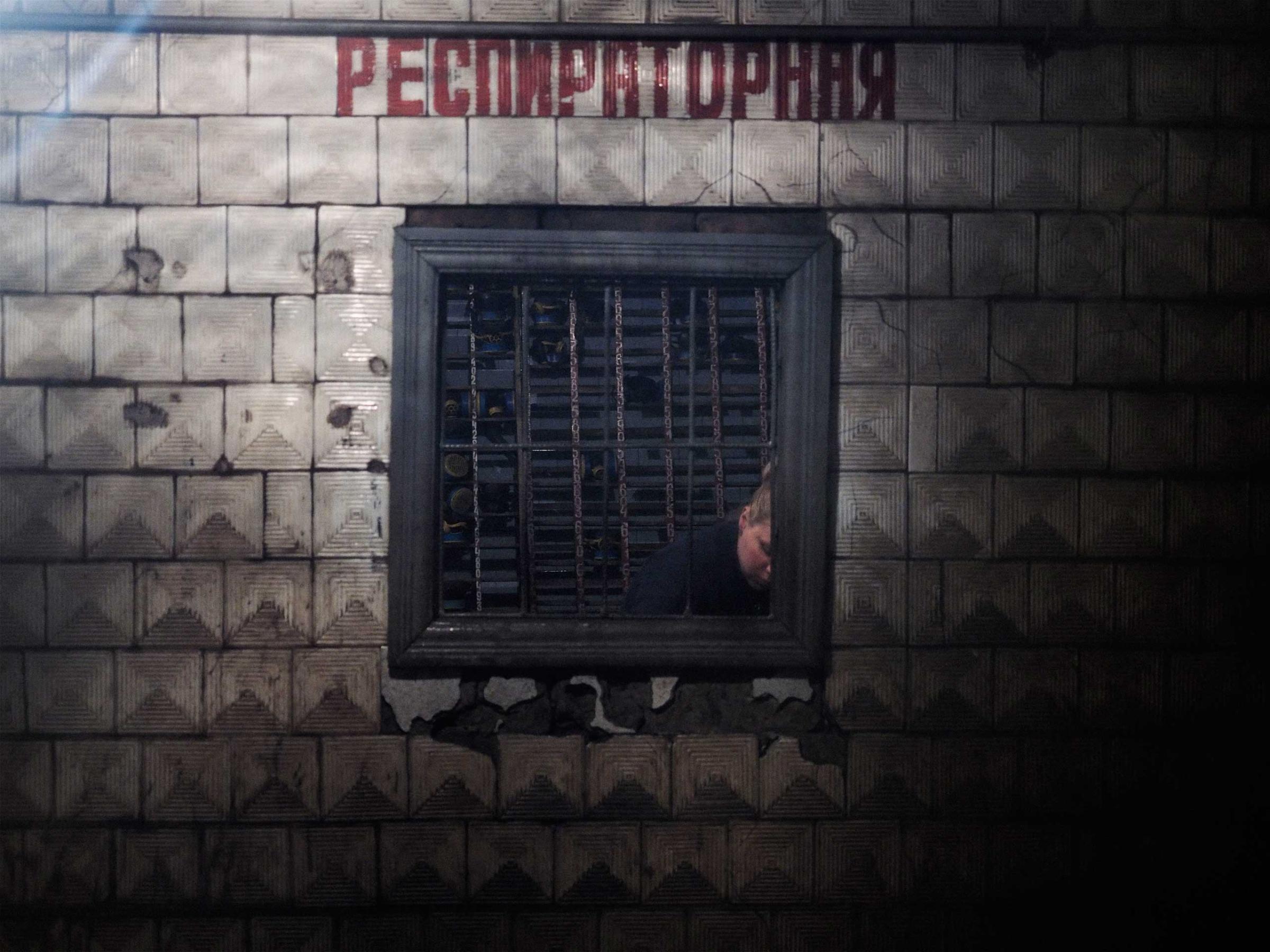

In July, Sessini was among the first on the scene after Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was downed by a missile, killing all 298 people aboard. That’s where he first came into contact with miners, when they were scanning the fields with firefighters, looking for victims. Aware that mining is the region’s backbone — some families have taken up the profession for generations — he was interested to go deeper and arranged with his translator to find an active mine that would let him in.

Ukraine’s country’s coal industry, Europe’s fourth largest, has been hit particularly hard by the conflict. Sixty-six of eastern Ukraine’s mines had been lost as of Nov. 18, according to Euracoal, a Brussels-based trade association, and just 60 remained in operation. The drop in production—Ukraine produced 2.3 million tons of coal in October, according to its State Statistics Service, down almost 60% compared to the same month a year earlier—has created a critical shortfall.

And it’s taken a toll on the thousands of families in eastern Ukraine that rely on the industry. The closures have halted paychecks for months and left many without work. Sessini described the miners as “a very proud people,” the “elites” of the community who are somehow keeping their humanity despite the war: “They try to show they are having a normal life but you can see in their faces a kind of anger and frustration and depression.”

Some families have fled the region in search of stability; others have moved underground into World War II–era bomb shelters. And while miners have mostly stayed on the sidelines of the conflict, desperation and resentment have pushed some into the arms of the separatists.

The Ukrainian government said in late December that it has arranged to import enough coal to avoid power outages in the coming months. The imports will help Ukrainians stay warm during what is sure to be a cruel winter, but until the two sides strike a peace deal, the suffering in eastern Ukraine will continue—above ground and below.

Jerome Sessini is a French photojournalist represented by Magnum Photos. Kira Pollack, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s Director of Photography. Follow her on Twitter @kirapollack. Andrew Katz is a homepage editor and reporter covering international affairs. Follow him on Twitter @katz.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com