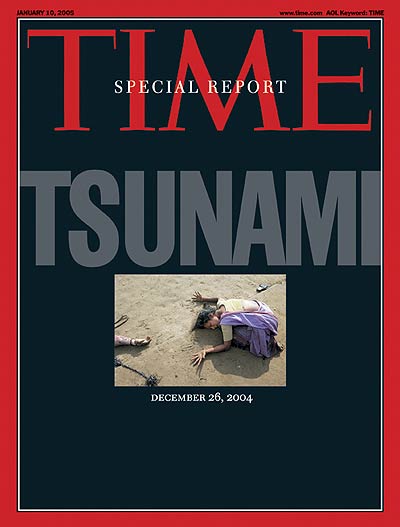

The day of Dec. 26, 2004, started with an earthquake, off the coast of Sumatra, and only got worse as the resulting tsunami hit coastal nations throughout the Indian Ocean.

As TIME explained in a special issue devoted to the devastation, the geology behind the tsunami caused a chain reaction of disaster:

Geologists describe the tectonics–the almost imperceptibly slow movement of massive plates–of the southern Indian Ocean as complex because a number of plates converge there. The floor of the Indian Ocean–the Indian plate–is moving north at around 2.5 in. per year, about twice the rate that your fingernails grow. As it moves, it is forced under the Burma plate to its east. Eighteen miles below the surface of the ocean, stresses that had been gradually accumulating forced the Burma plate to snap upward. That was a huge geological event, eventually measured at 9.0 on the Richter scale. The dislocation of the boundary between the Indian and Burma plates took place over a length of 745 miles and within three days had set off 68 aftershocks.

The movement of the plates sent shock waves through the water. Although tsunamis are often (incorrectly) called tidal waves, they have nothing to do with tides. They are, rather, very long waves–sometimes with hundreds of miles between their crests–that race along the ocean at speeds that can reach almost 500 miles an hour. In deep, open water, you would never notice even the most devastating tsunamis, which are often no more than a few inches high there. But when the water’s depth decreases, the wavelength shortens and the height of the wave increases. Then it crashes onto shore with the power to wreck buildings and throw trucks around as if they were Ping-Pong balls.

Tsunamis, moreover, have a trick up their watery sleeve, one that can trap the unwary. If the trough of a wave hits the shore before a crest, the first thing that anyone on shore notices is not water rushing onto the land but the opposite. That is what happened in Thailand and Sri Lanka. In the Sri Lankan town of Trincomalee, a hotel manager remembers the sea rushing out so the beach became magically full of gorgeous, colorful, stranded fish. “Men ran down to the shore with gunny-bags and stuffed them full of fish,” he says. On Phuket, Tiina Seppanen, a Finn, 20, on vacation with her sister and mother, also noticed that the tide had gone way out. “People were saying it was something to do with the full moon,” she says. And just as in Sri Lanka, people went on to the beach to collect the fish that had been stranded.

Tiina Seppanen survived, but more than 100,000 others did not. Read the rest of the special issue, here in the TIME Vault, to learn more about what happened: Tsunami

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com