The news that a copper box from the Revolutionary era had been unearthed in Boston drew excitement from history buffs eager to see what Paul Revere and Samuel Adams had chosen to preserve. Examination by x-ray suggested that it contains coins and documents from the 18th-century Massachusites, and its unveiling on Tuesday evening will provide a window into their world — which is exactly the purpose of burying a time capsule.

However, though countless news outlets (TIME included) have heralded the discovery of the time capsule, the copper box that Revere and Adams buried in 1795 isn’t technically a time capsule.

As time-capsule expert William E. Jarvis explained in his 2002 book Time Capsules: A Cultural History, one of the defining characteristics of a time capsule is that it must have an end date. A box placed in a building foundation — as the Boston box was in the cornerstone of the State House there — without specific instructions as to when it should be opened is instead, Jarvis writes, a “foundation deposit.”

But why put a box in a cornerstone if the point isn’t that someone in the future will find it? (Unless it contains a singing frog, which is an entirely different situation.)

It turns out that repositories in foundations and cornerstones have an ancient history, which Jarvis traces back thousands of years, to ancient Mesopotamia. The origins of these rituals are presumed to be connected to the sanctification of the building in question; then, as with some 13th-century European churches and cathedrals, holy objects might be placed in the foundation of a building that would be used for religious purposes.

“People have been putting things in the foundations of buildings for millennia,” says Knute Berger, another expert on the topic. (Berger and Jarvis are two of the founders of the International Time Capsule Society.) The reasons why, he says, are “spotty but interesting.” Some groups, he says, did intend to leave knowledge for the future — for example, a fraternal order called the Rosicrucians believed their founder had done so with his tomb — and some were making offerings, while others were merely doing the equivalent of signing a painting, as medieval workers did when they chiseled their initials into buildings.

Ceremonial cornerstones, often associated with rituals of Freemasonry, were common in early American history. In 1793, George Washington himself conducted just such a ceremony at the U.S. Capitol; it remains unfound and its contents are a mystery. The cornerstone deposit in Boston was likewise laid as part of a grand Masonic ceremony, on July 4th, 1795; at the time, Paul Revere was Grand Master of the state’s Freemason fraternity. On the day in question, the participants started at the old State House and processed to the location where the new one would be. Fifteen white horses drew the stone to its new home — one horse for each of the states in the union at the time, according to the current Secretary of the Commonwealth’s office — and Revere then delivered a speech congratulating those gathered on having been part of the establishment of a country where liberty and laws would prevail. “May we my Brethren, so Square our Actions thro life as to shew to the World of Mankind, that we mean to live within the Compass of Good Citizens that we wish to Stand upon a Level with them that when we part we may be admitted into that Temple where Reigns Silence & peace,” he said.

Revere’s remarks don’t mention the contents of the cornerstone being unearthed in the future, or whether the contents would indicate anything about the world of 1795. And when the box was found in 1855, during State House repairs, and resealed with added contents, it still wasn’t technically a time capsule.

But if that’s not a time capsule, what is?

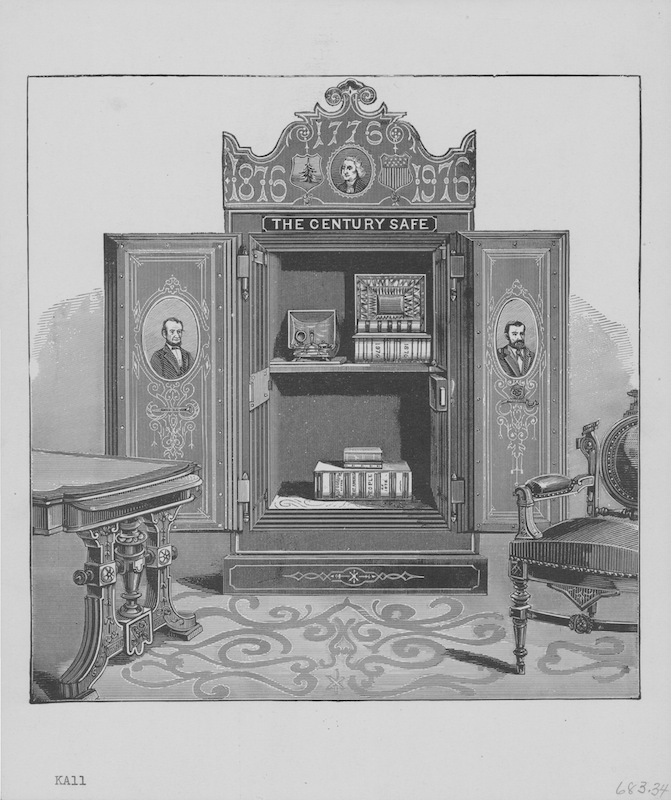

Jarvis’ book identifies the first-ever true time capsule as the Century Safe (pictured above) created for the 1876 Philadelphia World’s Fair and designed to be opened a century later, but the idea didn’t really take off until the 1930s or so. Perhaps interest in science around the turn of the 20th century sparked the birth of the fixed-end-date time capsule, guesses Berger: a true time capsule is like an experiment conducted with the scientific method, in that it has a set beginning and end.

The International Time Capsule Society is particularly concerned with the Crypt of Civilization, a time capsule conceived in 1936 and sealed in 1940, designed to be opened on May 28, 8113. It was meant to contain a complete record of civilization, including English lessons so that its eventual finders could read that record. The publicity surrounding the idea for the Crypt (which was first mentioned in an article by Thornwell Jacobs in Scientific American) also set off a fad, which prompted the Westinghouse Company’s decision to include a similar project in their exhibition for the 1938 World’s Fair. They called the project, meant to be opened 5,000 years later, a “time capsule” — widely seen as the first usage of the term. As TIME wrote when that project was announced, it was going to be buried 50 ft. underground and contain missives to the future from luminaries of the present. “Anyone who thinks about the future must live in fear and terror,” read Einstein’s.

When the capsule was buried in its steel-lined, concrete-stoppered tube in 1940, TIME reported that it contained much else as well:

Among the objects which went into it were a woman’s hat, razor, can opener, fountain pen, pencil, tobacco pouch with zipper, pipe, tobacco, cigarets, camera, eyeglasses, toothbrush; cosmetics, textiles, metals and alloys, coal, building materials, synthetic plastics, seeds; dictionaries, language texts, magazines (TIME among them), other written records on microfilm.

Still, whether or not the Boston box is a time capsule, we people of the present can learn from it. Though the capsule may include gold or silver, burying such treasure is more interesting than digging it up.

“The ritual is almost more important that the substance,” says Berger. And when it comes to that, it doesn’t even really make a difference whether the Massachusetts State House cornerstone technically fits into Jarvis’ definition of a time capsule. “What matters is that you were there.”

Read TIME’s original story about the 1940 burial of the World’s Fair time capsule, here in the TIME Vault: 5,000-Year Journey

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com