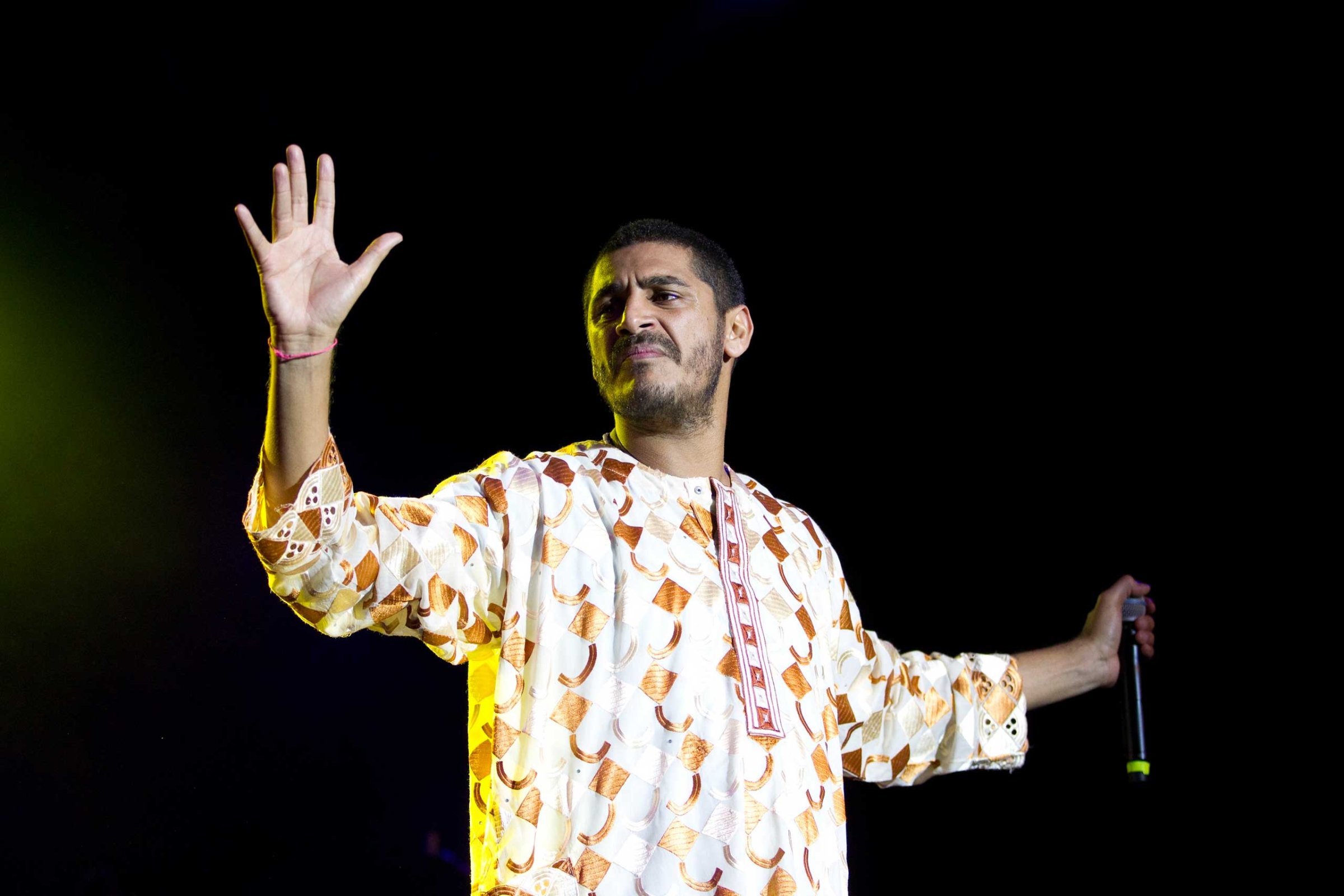

When Brazilian rapper Criolo takes the stage with his live band at the cavernous Fundição Progressso concert hall in Rio de Janeiro, a mass ‘rap-along’ breaks out as 6,000 fans chant along with him, throwing up hip hop hand gestures.

But there is nothing celebratory about the lyrics they repeat word for word. Criolo delivers a stinging social critique in song and rhyme, taking in Brazil’s crippling inequality, its drug problem, its violence and the growing obsession with consumerism that came with the country’s economic development. But the message is delivered as entertainment, not lecture, because this is a show, not a political discourse.

“There is no way you can look at the Brazilian social panorama and do agreeable songs,” says Luiz Fernando Vianna, a music critic for the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper. “What Criolo manages to do is do this criticism with a little humor.”

In the late 1980s and 1990s, São Paulo’s Racionais MCs filled stadiums with an uncompromising hip hop sound. Heavily political, they operated outside Brazil’s cultural mainstream. Criolo, in contrast, has broken out and is accepted more widely in Brazil as an artist, not just a rapper catering to niche tastes.

“He constructs bridges,” says Rodrigo Savazoni, a contemporary culture researcher and writer. “It is rap with its hand outstretched.”

Stardom for Criolo, real name Kleber Cavalcante Gomes, came late. The 39-year-old had struggled for 20 years on the grassroots hip-hop scene in his home city of São Paulo when his 2011 album Nó Na Orelha (Knot in the Ear) took off. It took a more accessible approach, combining his incisive and poetic rhymes with his singing, a live band, and elements of funk, reggae and samba.

MORE: The Top 10 Best Songs of 2014

It won three awards at Brazil’s 2011 MTV Awards, including best song for ‘Não Existe Amor Em SP’ (There Is No Love In SP), a haunting lament to a vacuous, lonely metropolis. Brazilian music great Caetano Veloso appeared on stage with him to sing it.

The song connected with a wider sentiment in the city then being daubed in graffiti slogans calling for “more love.” Brazil struggles with staggering levels of violence—56,000 people were murdered in 2012 alone. “It became an alternative anthem,” says Rodrigo Savazoni.

Criolo’s new album Convoque Seu Buda (Call Your Buddha) presents a similarly-eclectic mix of styles, and has already been downloaded 250,000 since it was released for free on the internet earlier this month.

It confirms his status as a star with a wide appeal along Brazil’s segregated social pyramid, from his original fans in the low-income, densely-packed outer suburbs, or periferia, of São Paulo to inner-city bohemians.

“He reaches different social levels,” says André Ribeiro, a Criolo fan and teacher at a state school in São Paulo’s southern periferia.

Rogério Silva, a sociology professor from the Federal Institute of São Paulo, says purist hip hop fans like Criolo—whose name can be used as a pejorative term for black, or Afro-Brazilian, citizens in this Latin American nation—but can’t always understand his complex language. “He is more popular in the middle class,” he says.

Criolo’s new album includes one song, ‘Casa de Papelão’ (‘Cardboard House’), that eloquently targets a crack epidemic that has turned an entire area of São Paulo’s center into an addict city, called ‘Cracolandia’ or Crackland. A video for two rap numbers on the album—‘Duas de Cinco’ and ‘Cóccix-ência’ —presents a chilling vision of a slum, or favela of the future, in which the poverty and crime remain the same but the technology has moved on. “There is still time to avoid this happening,” Criolo told TIME.

MORE: The Top 10 Worst Songs of 2014

The favela in the video is Grajaú, the sprawling slum on São Paulo’s southern edge where Criolo used to live with his parents, immigrants from Ceará state in Brazil’s northeast, in a house piled high with books. His mother Maria Vilani runs a weekly ‘philosophy café’ discussion group and his father Cleon is a metalworker. His great-grandfather, he says, was a slave.

Criolo and his four brothers and sisters grew up at the sharp end of Brazil’s notorious unequal society, living at one point in a leaking wooden shack. He lost many friends to the violence that blights the periferia. “I have seen things I wouldn’t wish anyone to see,” he says.

Criolo discovered hip hop age at eleven, listening avidly to rappers from New York and Los Angeles

In Criolo’s view, Brazilian problems stem from its modern history—a vicious colonization in which Portuguese invaders killed and enslaved indigenous tribes, followed by centuries of slavery. “You already start like this,” he says. Later came the military dictatorship that ran Brazil for two decades until 1985.

Yet he will not comment on Brazil’s recent presidential election, which saw the incumbent Dilma Rousseff secure a second term after one of the most gripping contests in recent Brazilian history. “It becomes innocent to talk about politics when we don’t have a structure to study politics,” he says. “Those who govern us are not interested in putting certain areas in school material.”

MORE: The Top 10 Best Albums of 2014

Brazil has its own version of hip hop—a raw, electronic sound from Rio favelas called ‘funk’. In recent years São Paulo has stolen the other city’s thunder with a style dedicated to conspicuous consumption called ‘ostentation funk’.

Criolo satirizes consumerism as a panacea for social exclusion in a disco-rap duet with singer Tulipa Ruiz called ‘Cartão de Visita’ (or Business Card). “I wouldn’t say extreme riches, I would say extreme futility,” he says. It draws the biggest cheer when Tulipa Ruiz joins him onstage to sing it.

But Criolo insists he is not pessimistic, just realistic. He says the urban occupations he also raps about are an example of positive change. He played an “emotional” show for activists in the northeastern city of Recife, after an occupation in an abandoned port area being developed was violently evicted by police.

“There is something bigger than all of this. Our generation. This new young generation that is being created, with new ideas, the desire to change the world,” he says. “There is not going to be a musician who manages to write this.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com