This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

International Human Rights Day (December 10) and the recent airing of the Ken Burns series The Roosevelts: An Intimate History have focused renewed attention on the life and work of Eleanor Roosevelt. While such interest is welcome and long overdue, the fact remains that Burns overlooked much of ER’s life and work in a series that purported to include her as an equal to her uncle Theodore and her husband Franklin.

As a savvy producer and consumer of television, ER would have been the first to appreciate Burns’s series on her family. She would have welcomed his interest in their lives and accomplishments but she would have been puzzled and dismayed at the amount of time devoted to her private life. She would have been particularly unhappy about the portrayal of the last seventeen years of her life (a mere 35 minutes in a fourteen-hour program). This period is a complete mystery to most Americans who usually associate ER with Franklin and assume that her role in American life ended with his death in 1945 or that her postwar life merely echoed his New Deal.

Neither of these statements is true. From 1945 until her death in 1962, ER took the ideas about community, inclusion and democracy that she, her husband, and uncle espoused, and pushed them much farther than Theodore or Franklin ever dreamed. However, because she usually exercised political power indirectly and often played down or obscured her own achievements, ER’s contributions are often overlooked and undervalued.

Nevertheless she left a voluminous record, and it is possible to tell the story of ER’s post-White House life in a compelling, coherent fashion because she based much of what she did on three key concepts: political courage, civic education and citizen engagement. In terms of political courage, ER’s postwar career coincided with the early years of the Cold War. Americans of that era feared communist incursion and nuclear attack. ER fought those politicians who preyed on those fears, speaking out against the ravages of McCarthyism at home and urging her fellow Americans to spend more time improving democracy and less time witch hunting. At a time when many Americans believed non-aligned countries like India were communistic, she was among the few to argue that befriending nations who refused membership in either the US or the Soviet camp would be smart politics.

When the US government sharply limited travel to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, she dared to visit Yugoslavia once and the Soviet Union twice. Her 1957 interview with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev was front page news and carefully monitored by both the State Department and the FBI, neither of whom cared much for her views or her politics. In fact, ER’s progressive politics and insistence on freedom of speech and association made her a target of the FBI and its director J. Edgar Hoover. For almost forty years, beginning in 1924 when she supported the US’s entrance into the World Court and American participation in the League of Nations, the Bureau kept a file on her. At her death it ran to thousands of pages, much of which remains redacted.

Civic education for ER took many forms. Besides “My Day,” her syndicated newspaper column, which ran six days a week for more than twenty years, ER wrote 27 books and hundreds of magazine articles on topics ranging from Cold War politics to raising children. During her White House years alone she hosted six different sponsored radio programs of her own and appeared on countless others. In the last seventeen years of her life she hosted two additional radio programs and three public affairs television programs including one, “Prospects of Mankind,” that ran on the precursor to PBS.

ER’s view of citizen engagement was similarly expansive. On a partisan basis, citizen engagement meant doing all she could to shore up the liberal wing of the Democratic Party—everything from helping to found Americans for Democratic Action to mediating the fight between Democratic conservatives and Democratic liberals over the issue of civil rights at the 1956 Democratic convention. At the same time she continued to work with Republicans on issues of mutual concern.

Another important aspect of ER’s civic engagement philosophy was her support for American labor. ER did more than foster the labor movement, she actually joined it. In 1937, one year after she started writing “My Day,” she became a member of what is today the Newspaper Guild, AFL-CIO. Despite allegations that her membership implied communist affiliation, she remained a member for over twenty-five years. Indeed, her union card was in her wallet when she died. ER also numbered many union leaders among her personal friends. She was particularly close to United Auto Workers Union president Walter Reuther. Reuther and ER worked and relaxed together—staying at each other’s homes and befriending each other’s families.

During the postwar years, ER gradually became a strong supporter of public sector unions, and vigorously led an effort to defeat so called “right-to-work laws” in six states. She was a keynote speaker at the AFL-CIO merger convention in 1955, a merger she had championed for twenty years. When A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, asked her to join the National Farm Labor Advisory Committee in 1959, despite failing health she agreed. She attended meetings, wrote columns and testified before Congress on behalf of migrant farm workers.

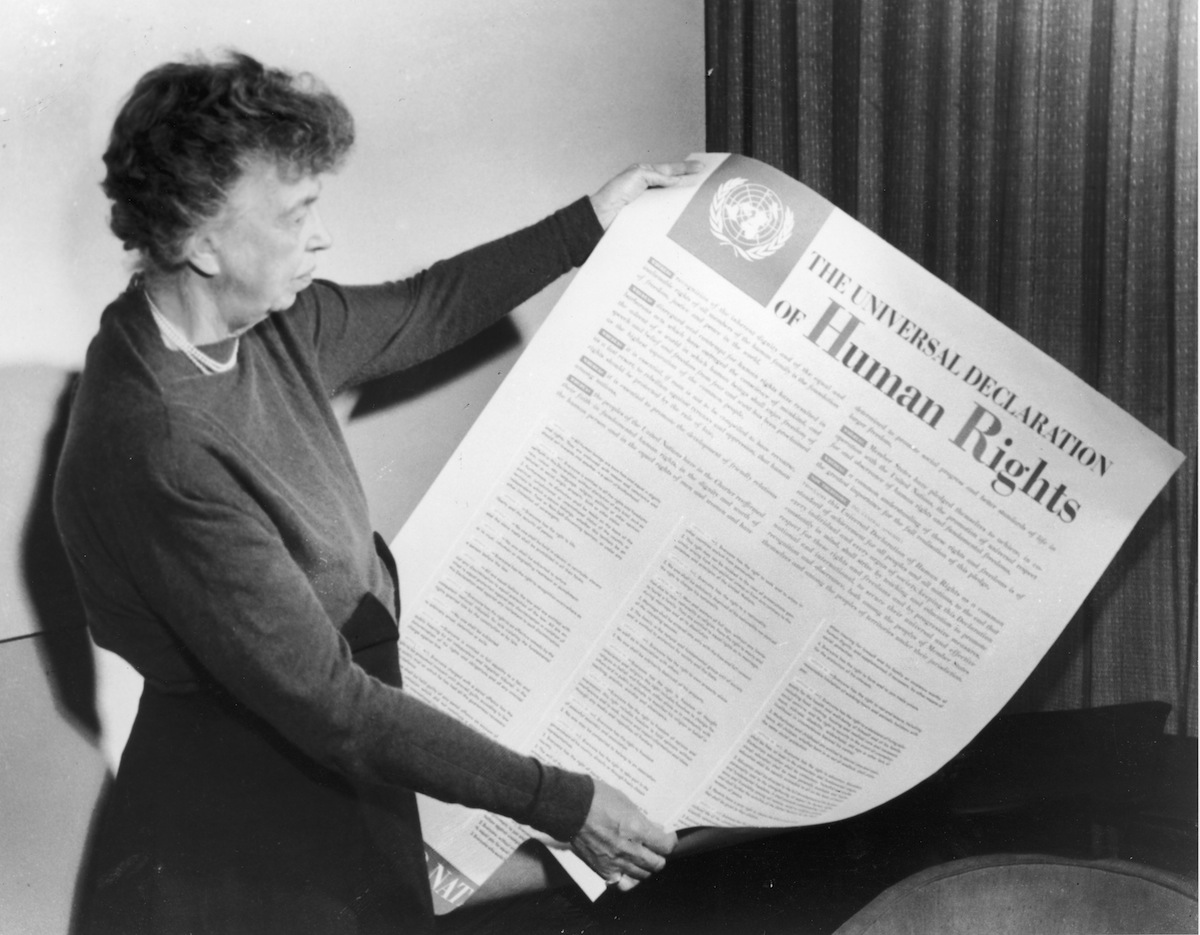

As for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Burns rightfully noted ER’s centrality to its creation and passage, but failed to mention its significance to subsequent history. According to Harvard Law Professor Mary Ann Glendon, author of a well-regarded book on ER and the UDHR, “the most impressive advances in human rights–the fall of apartheid in South Africa and the collapse of the Eastern European totalitarian regimes–owe more to the moral beacon of the Declaration than to the many covenants and treaties now in force.”

To the very end of her life, political courage, civic education and citizen engagement governed ER’s activities. Her last major undertaking, the chairmanship of President John F. Kennedy’s Commission on the Status of Women, yielded a report in which the federal government documented for the first time the inequities women faced in the home and in the workplace. The report called for an end to discrimination in all walks of life and recommended family supports such as paid maternity leave and quality, affordable child care. It reinforced the importance of unions, and it challenged the United States to become a world leader in the struggle for human rights.

Clearly ER was a critical link between her uncle Theodore and her husband Franklin. She was also an integral part of Franklin’s presidency. Yet her own achievements were substantial, long-lasting, and it can be argued, critical to the lives of millions of people around the globe. Ken Burns was right to include ER in his portrait of the Roosevelts. He just didn’t do her justice.

Mary Jo Binker is one of the editors of the Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, a sponsored project of The George Washington University. Brigid O’Farrell is an affiliated scholar with the project and the author of “She Was One of Us: Eleanor Roosevelt and the American Worker.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com