The early days of the AIDS epidemic were dangerous not just because a killer virus was sweeping across America, but because the mysterious syndrome spawned its own damaging myths.

On this day, Dec. 10, in 1981, the New England Journal of Medicine published three landmark articles and an editorial attempting to make sense of the deadly immune deficiency, which had been identified a scant six months earlier. By December, according to the BBC, the condition had been found in 180 Americans and killed 75, nearly all of them gay men.

Doctor Michael Gottlieb was among the first to recognize the chilling threat the crisis posed. When the epidemic began, 33 years ago, Gottlieb himself was 33 and an assistant professor of immunology at the UCLA Medical Center, eagerly searching for interesting “teaching cases,” according to a profile in the American Journal of Public Health.

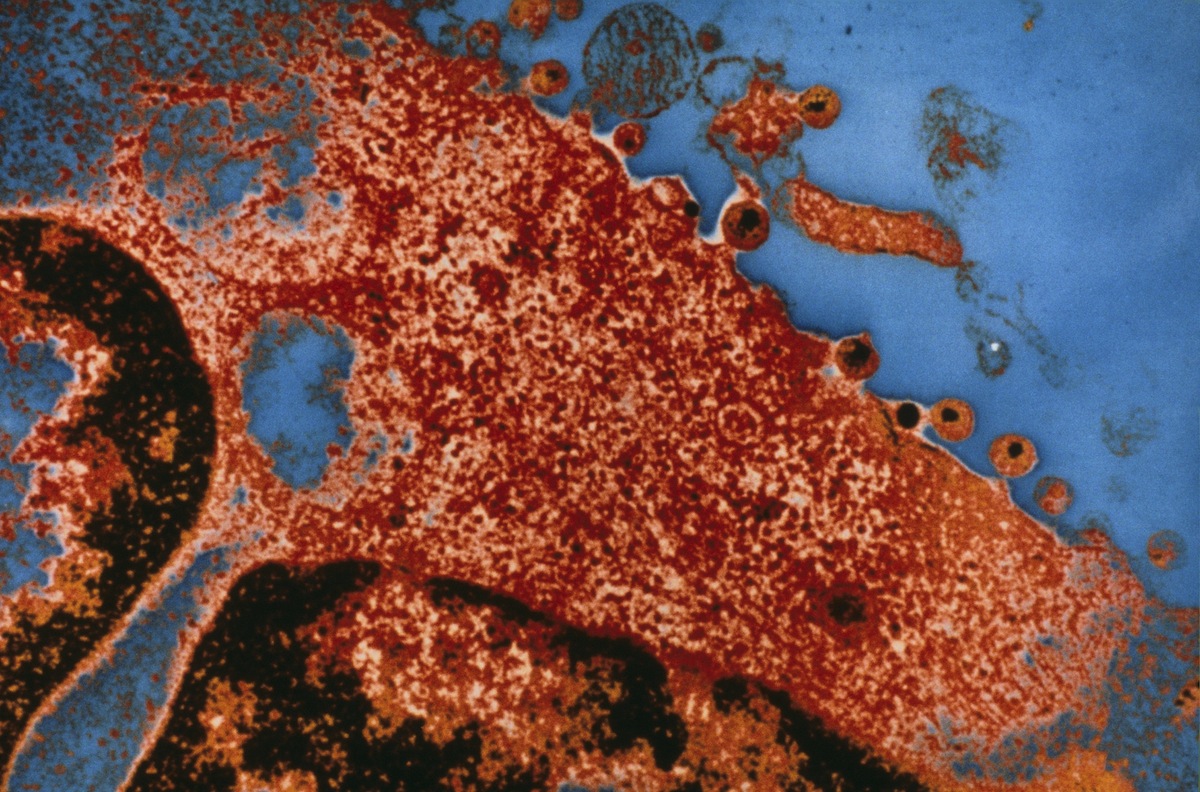

One case that caught his attention was a harbinger of the devastation to come: a young gay man with an array of serious health problems more common to organ transplant patients than otherwise robust young people. Gottlieb and his fellow immunologists found that the man had virtually none of the “helper” cells that fight infection. After coming across several similar cases, the doctor suspected that some new, unknown virus was responsible. He told the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine that it might be “a bigger story than Legionnaire’s disease.”

To warn the medical community, Gottlieb put out his preliminary findings in the weekly report issued by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. By the time the journal article came out in December, other doctors from around the country had reported similar cases and were hunting for a cause.

One early theory pegged the spread of the disease — which the CDC named AIDS — to a club drug called “poppers,” although the correlation quickly broke down. New evidence that the virus was transmitted through bodily fluids emerged when heterosexual drug users began reporting symptoms, apparently after sharing dirty needles.

By then, however, hysteria over the agonizing illness had led to a proliferation of myths about its transmission. Those myths lingered long after they were disproved, adding another layer of stigma for the syndrome’s victims.

For example, in 1988 — by which time AIDS was well enough understood to make such claims preposterous — a sensationalistic book, Crisis: Heterosexual Behavior in the Age of AIDS, stirred new panic with old assertions about how the syndrome was spread. According to TIME’s review of the book, the authors suggested that contracting AIDS was as easy as using the toilet after someone with the virus, being bitten by the same mosquito or even getting to second base. This last was meant as a literal warning to baseball players, not a metaphor for heavy petting: a player could catch the virus by sliding onto the base “if, by chance, an infected player has bled onto it,” the book warned.

When confused — and terrified — callers jammed AIDS hotlines, one epidemiologist fumed, “This is the AIDS equivalent of shouting ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater.”

Read more about the early search for the HIV virus, here in TIME’s archives: Hunting for the Hidden Killers

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com