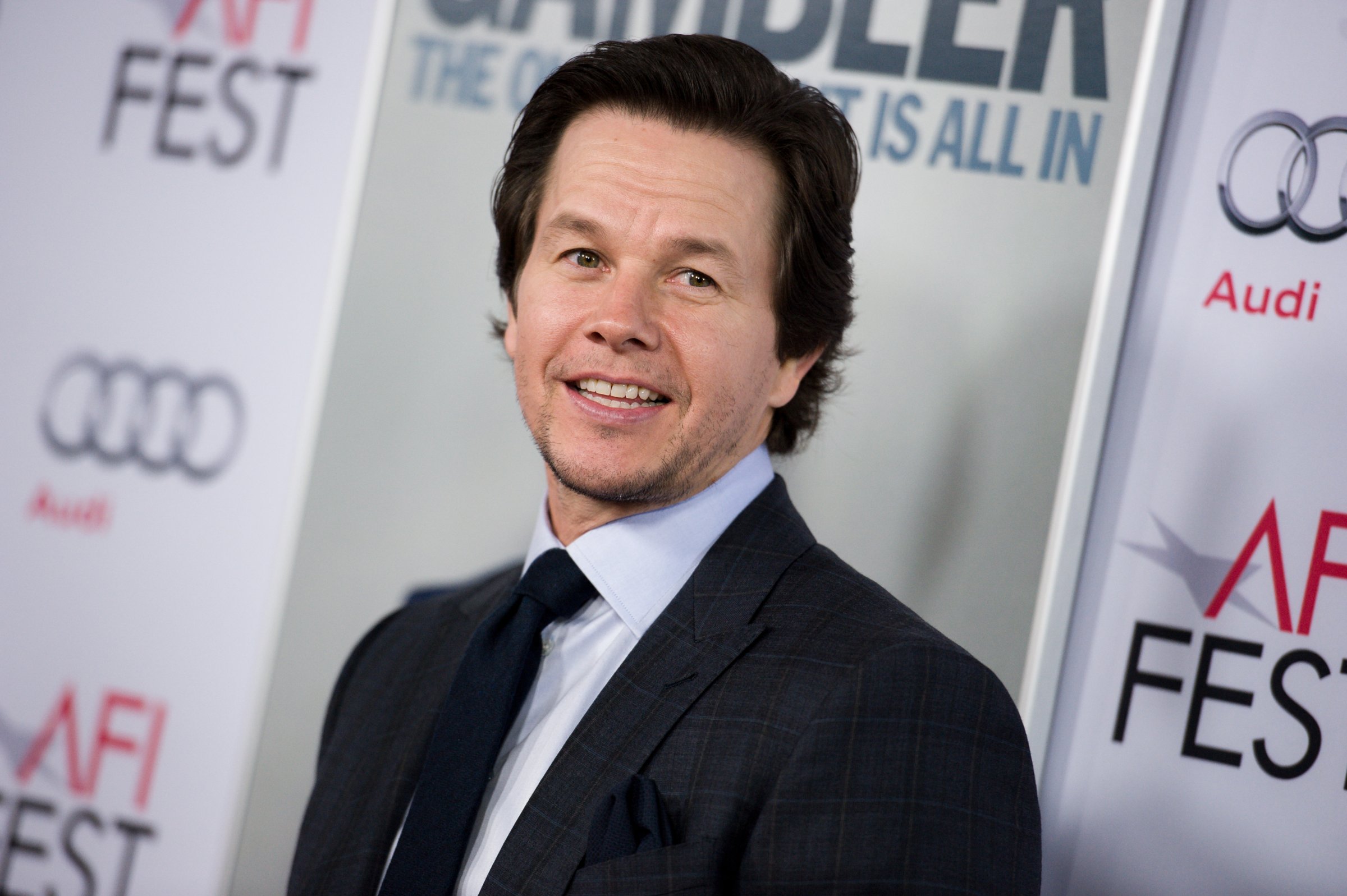

Evidently, getting completely absolved in the court of public opinion isn’t enough for Mark Wahlberg.

The actor, whose new film The Gambler is to be released this month, has filed a petition to the governor of Massachusetts asking to be pardoned for crimes he committed in the late 1980s, before his rise to fame as a rapper and, later, an actor. Most notable among Wahlberg’s crimes were his blinding a man of Vietnamese extraction after knocking out another Vietnamese man with a stick.

These racist crimes, described in detail here, happened in 1988, some three years before the first release from Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch and five years before Wahlberg’s acting debut. Wahlberg paid his debt to society by serving 45 days of his sentence, but his debt was not so onerous as to have any meaningful effect on the actor’s career. For all Wahlberg’s complaints, it would seem that his crimes have affected his public life shockingly little.

While actresses in particular see their working lives derailed over even a rumor of legal drama, Wahlberg’s past crimes gave him, first, an essence of danger exploited in Calvin Klein ads and, later, a convenient triumph-over-adversity narrative trotted out when confronted with a journalist who even remembered the crimes in the first place. Wahlberg cites, in his petition, the potential for his past convictions to preclude him from receiving a concessionaire’s license to run restaurants (which, with his Wahlburgers chain, he does anyway) and to keep him from working with law enforcement to help at-risk youth to the hyper-involved degree he desires (though he works with law enforcement anyway). To describe the impact his past crimes have made on his life is to split hairs finely.

But the pardon Wahlberg desires isn’t pragmatic, to help him move forward with his life; it’s aesthetic. Wahlberg clearly believes he is not the same person he was when he committed youthful crimes. So, too, does the public: If Wahlberg were widely perceived as a violent, racist criminal, his career would be less robust, or, at least, his crimes would come up in conjunction with his name. The audience that hasn’t forgotten has forgiven; Wahlberg’s Transformers sequel was one of the year’s top-grossing movies.

But to petition for a pardon pushes his redemption narrative beyond sense. Turning over a new leaf is one thing; declaring that crimes effectively did not happen is quite another. “[R]eceiving a pardon,” Wahlberg writes in his petition, “would be a formal recognition that I am not the same person that I was on the night of April 8, 1988.” But people without a major public profile could never expect to receive similar absolution from the state. Wahlberg is special, in that he is one of his generation’s best-known and -loved movie stars. He’s not so special that he is entitled to have his past officially erased.

As it stands, Wahlberg’s narrative, for those who choose to remember it, is itself a compelling story of overcoming difficult circumstances and youthful indifference to the law. Had Wahlberg not petitioned the state of Massachusetts to wipe his record clean, he’d seem more like the person he wants to be: A person who has changed and become better. But in declaring that he is so very special that past crimes shouldn’t stick to him, Wahlberg’s entitlement and disregard for consequences seems to prove that, though he’s done a great deal of good works in the time since 1988, he’s still very much the same person — someone for whom consequences don’t matter. His petition has the unfortunate effect of making Wahlberg’s past charity work, as well as his squeaky-clean personal life, look like a P.R. campaign to wipe his slate clean. (“More privately, I make it a point to attend church nearly every day,” he writes, radically redefining the term “privately” to mean “publicly.”)

That Wahlberg has served his time and moved forward with life sends a message that anything is possible for people in dire circumstances. For the state to say he never committed a crime at all would send a message that anything is possible for a celebrity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com