Just like the Pentagon’s recent real-world wars, its latest dispatch from the front in the battle against sexual assault contains both good and bad news.

There are enough numbers crammed into the document that military boosters can hail the progress that has been made, while critics can claim the Defense Department still isn’t doing enough.

“There have been indications of real progress,” Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said as he released the report Thursday afternoon, but “we still have a long way to go.”

According to that latest accounting, the bad news is that reported assaults continue to rise—from 3,604 in 2012, to 5,518 last year, and to 5,983 in 2014 (the report charts fiscal years, which end Sept. 30). That’s an 8% jump in the past year.

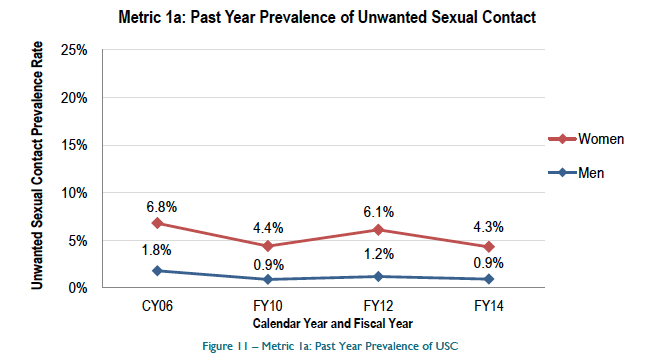

The good news, the 1,136-page report says, is that reforms in handling sexual assault have encouraged more victims to come forward and not cower in secret. The study estimates that while only 10% of alleged victims came forward in 2012, 25% did in 2014. The number of active-duty women complaining about unwanted sexual contract dropped from about 6.1% last year to 4.3% in 2014 (for men, the number fell from 1.2% to 0.9%).

An anonymous Rand Corp. survey of military personnel projected that approximately 19,000 had been subject to unwanted sexual contact in 2014 (55% of them male), 27% less than the 26,000 estimated in 2012. It was that spike—up from 19,300 in 2010—that focused attention on the problem and led to a host of changes into how the military investigates and prosecutes alleged sexual assaults.

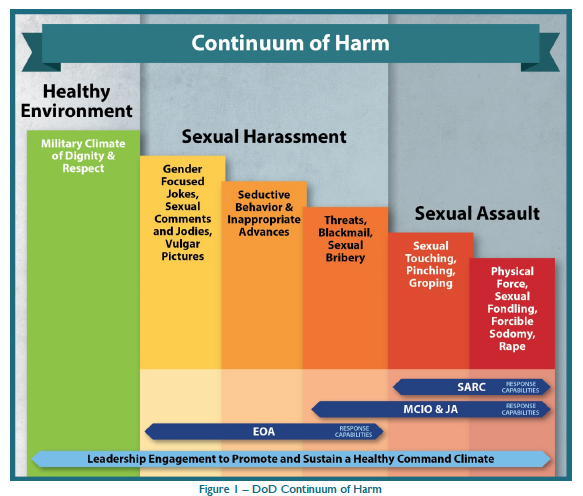

Commanders are no longer free to reverse court-martial convictions, and each alleged victim is assigned a lawyer. When a commander and prosecutor disagree over whether a court martial is warranted, civilians are called in to review such cases. Statutes of limitations on such crimes have been scrapped. Anyone convicted of sexual assault in the U.S. military gets at least a dishonorable discharge.

But the tribal nature of military service persists: 62% of the women alleging unwanted sexual contact felt they had been shunned or punished for complaining. “The Department was unable to identify clear progress in the area of perceived victim retaliation,” the study said. “The news is a mixed bag,” says Elspeth Ritchie, a retired Army colonel who dealt with the issue as a military psychiatrist. “The numbers persist despite all the public education campaigns.” Reducing retaliation “is the key to further progress,” she adds. “It is very frustrating that so little progress has been made.”

The Pentagon has spent decades trying to rid its ranks of sexual predators—and encouraging victims to come forward—but progress has been slow. “An estimate of 20,000 cases of sexual assault and unwanted sexual contact a year in our military, or 55 cases a day, is appalling,” Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., said. “There is no other mission in the world for our military where this much failure would be allowed.” Gillibrand plans to renew her push to take prosecution of such cases away from the alleged perpetrator’s commanders and give it to a corps of independent military lawyers.

“It is unfair to the commanders to put them in this position,” said Don Christensen, who recently retired as a top Air Force prosecutor. “It is a system set up for failure.”

Dealing with sex among young men and women—especially when there is a commander-commanded relationship, and liquor, or other such substances, are involved—is difficult under the best of conditions. And the military lacks the best of conditions, given its stresses, its work-hard, play-hard ethos, and the fact that the service attracts its fair share of dolts (like the sailor, according to a report Wednesday, who allegedly filmed female officers showering aboard their shared submarine).

As women have become an increasing share of the U.S. military—they now account for 15 of every 100 Americans in uniform—the service’s macho culture hasn’t kept pace. “Sexual harassment stems from certain widespread cultural attitudes that have been prevalent through the ages,” a 1993 Army report said. “Women have lived under male protection–benevolent or otherwise–thereby being forced to live by the rules of men who dominate them.”

That’s slowly changing, with the emphasis on slowly.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com