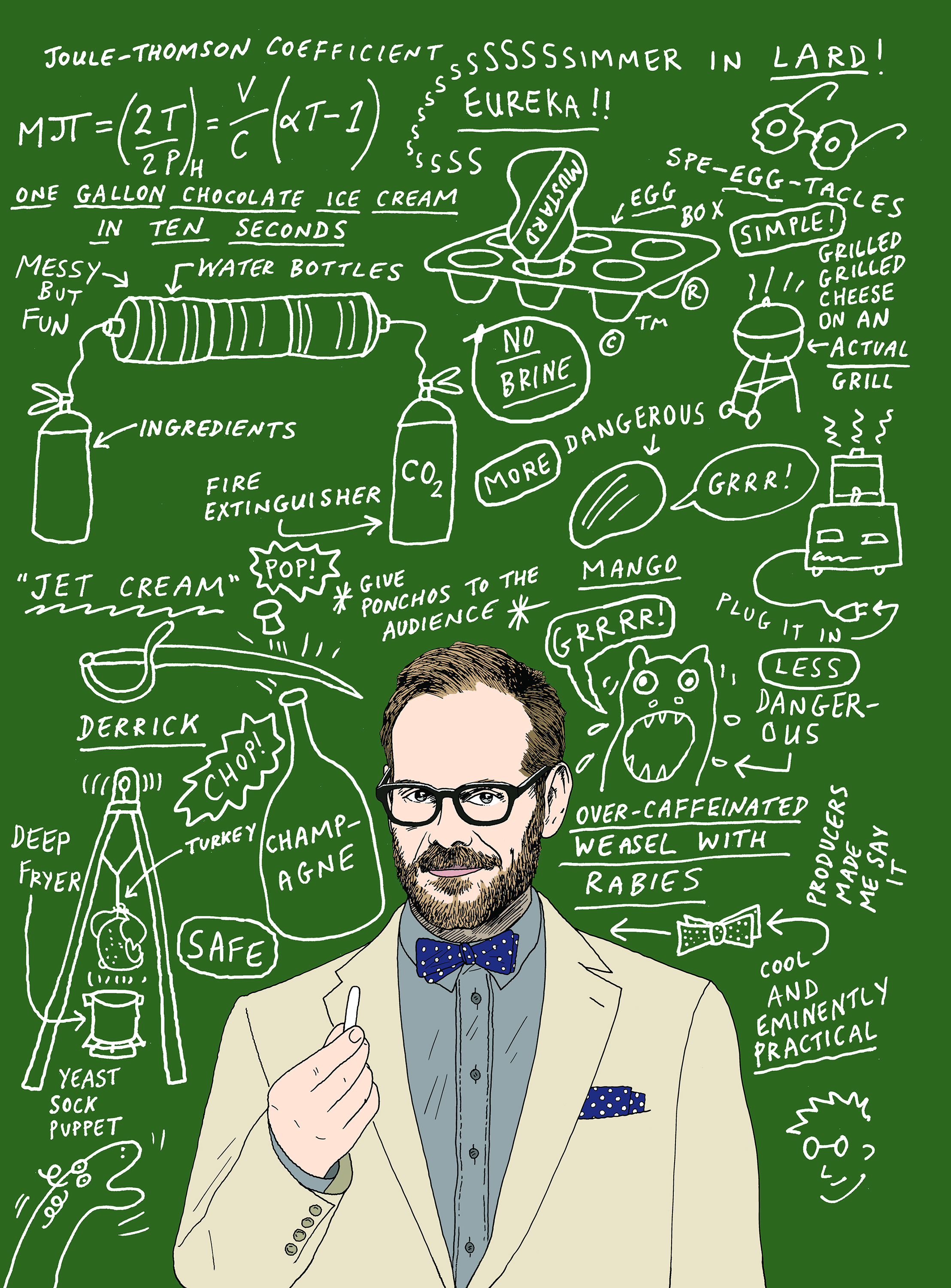

It was a Saturday night in November in New York City, and at the Beacon Theatre–the ’20s-era 2,800-seat house that the Allman Brothers Band sold out so many times–the TV chef Alton Brown opened his own sold-out show by rapping (rapping!) over a remixed version of the theme song for his first TV show, Good Eats. He cited his trade’s excesses and hypocrisy while wearing doughnut-shaped bling and a fedora reminiscent of Run-DMC. In ensuing numbers, Brown sang ruefully in his Muppet-like voice of an airport shrimp cocktail that induced gastric distress after takeoff and endearingly of his attempts to teach his daughter kitchen basics. He also demonstrated two ingenious cooking contraptions of his own creation: the Jet Cream, which employs two fire extinguishers and the Joule-Thomson effect to freeze a gallon of ice cream in 10 seconds, and the Mega-Bake, a 1963 Kenner Easy-Bake Oven supersized by way of 1,000-watt stage lights. The thing draws 450 amps. Brown buttressed the singing and cooking with monologues and a Twitter-fueled audience Q&A. Flatulent puppets punctuated the preshow and intermission. By the end I had laughed and marveled but had eaten nothing except for half a bag of Peanut M&M’s that Brown’s agent had given me. Just what kind of food show was this?

Brown has taken his Edible Inevitable Tour all over the country, selling more than 150,000 tickets since it kicked off in October 2013. The tour’s fourth and final leg, which will cover 37 cities, runs from February to April. For three two-month bursts, he has performed six shows a week, rolling his truck and two buses into towns from Austin to Wichita, eating whatever the locals recommend, performing and then packing up. He loves touring and has learned a lot, Brown says, adding, “The best doughnut in the United States? Memphis, bar none–Gibson’s Donuts. The best restaurant? Fong’s Pizza in Des Moines. It’s a pizza place stuck inside a tiki bar with the decor of a 1960s Chinese restaurant.” But he seems to have hit the road in search of answers to much tougher questions, ones concerning faith, life and the future of food education.

Brown, 52, first turned up on Television in 1999, with Good Eats. He hadn’t followed a recognizable TV-chef path. Although he was born in Los Angeles, he and his parents moved cross-country to their home state of Georgia when he was 7. When Brown was in sixth grade, his father–Alton Sr., who owned a local radio station and a weekly newspaper–killed himself. “He worked himself to suicide,” Brown says. His mother married again, and the only child had to cope with stepsiblings. Brown says he barely graduated from high school and that it took six years and multiple schools for him to finish college, where he studied film and theater.

He eventually established a career in Atlanta as a director and cinematographer. He did camera work on Spike Lee’s School Daze and R.E.M.’s video for “The One I Love.” But he spent much of his spare time watching cooking shows, and he started thinking: If he knew food better, maybe he could leverage his filmmaking instincts to make a great show. In 1994 he abandoned his trade to attend the New England Culinary Institute in Vermont. After cooking school, he interned with a French chef and found the experience maddening. His boss offered edicts, not explanations. So Brown hatched his formula: he would study the history and science behind an ingredient or a process and then present what he had learned in a playful yet punctilious fashion. He had no signature flavors, only skills. His Southernness, the crutch for so many TV chefs, was gentle and urbane.

Good Eats became a cult hit, owing to Brown’s nerdy humor–he often leaned on props and pop-culture references–and MacGyver-like kitchen methods, for which he expressed utter conviction. He disdains so-called unitaskers. He made beef jerky with air-conditioner filters and a box fan. Indeed, the Good Eats fan often finds himself (and it is generally, Brown says, “himself”) fishing around in the garage for some unusual tool to make the perfect dish. Brown’s coconut cake calls for a hammer and screwdriver.

The overlap is nearly perfect, Brown says, between his fan base and Doctor Who’s. “I gave food geeks their first major congregation point,” he says. It helped that he looked the part. For most of Good Eats’ run, Brown wore unstylish glasses and had spiky hair, and he covered his then paunchy frame with Hawaiian shirts. Now he is trim, with a distinguished beard–he shaved it off last year but couldn’t stand his face without it–and says good clothes became his chief indulgence after he sold his twin-engine Cessna.

Two years ago, after 14 seasons and a Peabody Award, Brown pulled the plug on Good Eats. “I said, ‘I’m not gonna get canceled. I quit!'” Brown recalls. The success of all kinds of competition shows, including Bravo’s Top Chef, had made the once educational Food Network swerve toward cook-offs. Brown’s show had seemed to him perilously at odds with what increasingly looked like the Game Show Network for gluttons. The network’s prime-time lineup now features frequent airings of the 2009 arrival Chopped and the newer Cutthroat Kitchen, which throws out-there obstacles at well-meaning cooks who must make gourmet food on a hot plate or without a chef’s knife. The show’s host, the sadist behind the sabotages, as they’re called, happens to be Alton Brown.

Brown notes with a hint of despair that the Food Network pays him more for each episode of Cutthroat Kitchen–for which he’s simply talent, playing “a Bond-villain version of myself”–than he earned for entire early seasons of Good Eats, a show he usually wrote, produced, directed and starred in. (Brown’s wife DeAnna also produced the show.) Now when people ask him what he does for a living, he says he’s a game-show host.

“People joke about midlife crises,” Brown says. “‘Ooh, he’s gonna get a red sports car and a mistress.’ But really, I’m sitting here wondering what I’m going to be doing with the rest of my life. Is that a crisis? Yeah. But should I ignore that or run away from it? Not at all.” The tour provided him a chance to do something new and auteurish–free of influence from network executives and sponsors–while keeping very busy.

Brown has always been a workaholic. He says he has no friends except for work colleagues: “I won’t pretend it’s some Calvinist virtue. It’s an addiction.” Brown says he is also struggling with some family troubles, which he prefers not to discuss in detail.

He’s also in the midst of a crisis of faith. Brown, who was baptized in 2006, says he’s “on a break” from his church. He says he can no longer abide the Southern Baptist Convention’s indoctrination of children and its anti-gay stance. He’s now “searching for a new belief system.”

As for work? He’s shooting a new batch of Cutthroat Kitchen episodes this month, and then he imagines he’ll be done, not just with the show but perhaps with the Food Network. He wants to make a movie, he says, with a culinary basis. And he’s planning a Good Eats–like web series. “I’m less motivated now by money than I used to be,” he says. “I spent all of 2009 working. I don’t remember anything that happened that year. I hate that. I’m at a point now in life where I need to remember stuff.”

He knows he needs some time to travel and read, he says. Brown is an obsessive rereader. Each year it’s The Great Gatsby–he says he can’t read it without weeping–and The Sun Also Rises. Every five years, it’s Moby Dick. These books are wasted on high schoolers, he says. “How can you ask them to understand the struggle against the unknown? Against God?” he asks. “You can’t.”

Brown says he’s a loner, and I believe him. But I think back to something he said earlier. He had mentioned that he talked with some anthropologists before going on tour. And they told him that there were only two activities humans prefer to do in groups: laugh and eat.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jack Dickey at jack.dickey@time.com