Attorney General Eric Holder has begun drafting plans to continue his work rebuilding the relationship between local law enforcement and the black community after he leaves public office next year.

“This whole notion of reconciliation between law enforcement and communities of color is something that I really want to focus on and to do so in a very organized way,” he said Tuesday in an interview with TIME. “Not just as Eric Holder, out there giving speeches—though certainly that could be a part of it—but to have maybe a place where this kind of effort is housed and to be associated with that kind of an entity.”

His preparation comes at a time when the nation’s top law enforcement officer has launched a national tour to meet with black leaders and law enforcement around the country, amid daily protests over grand jury decisions in New York City and Ferguson, Mo., to not bring charges against police officers who killed unarmed black men. On Monday, Holder spoke at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, a civil rights landmark, and on Thursday he will travel to Cleveland, where a police officer recently shot a 12-year-old black boy, Tamir Rice, who was playing with an air gun.

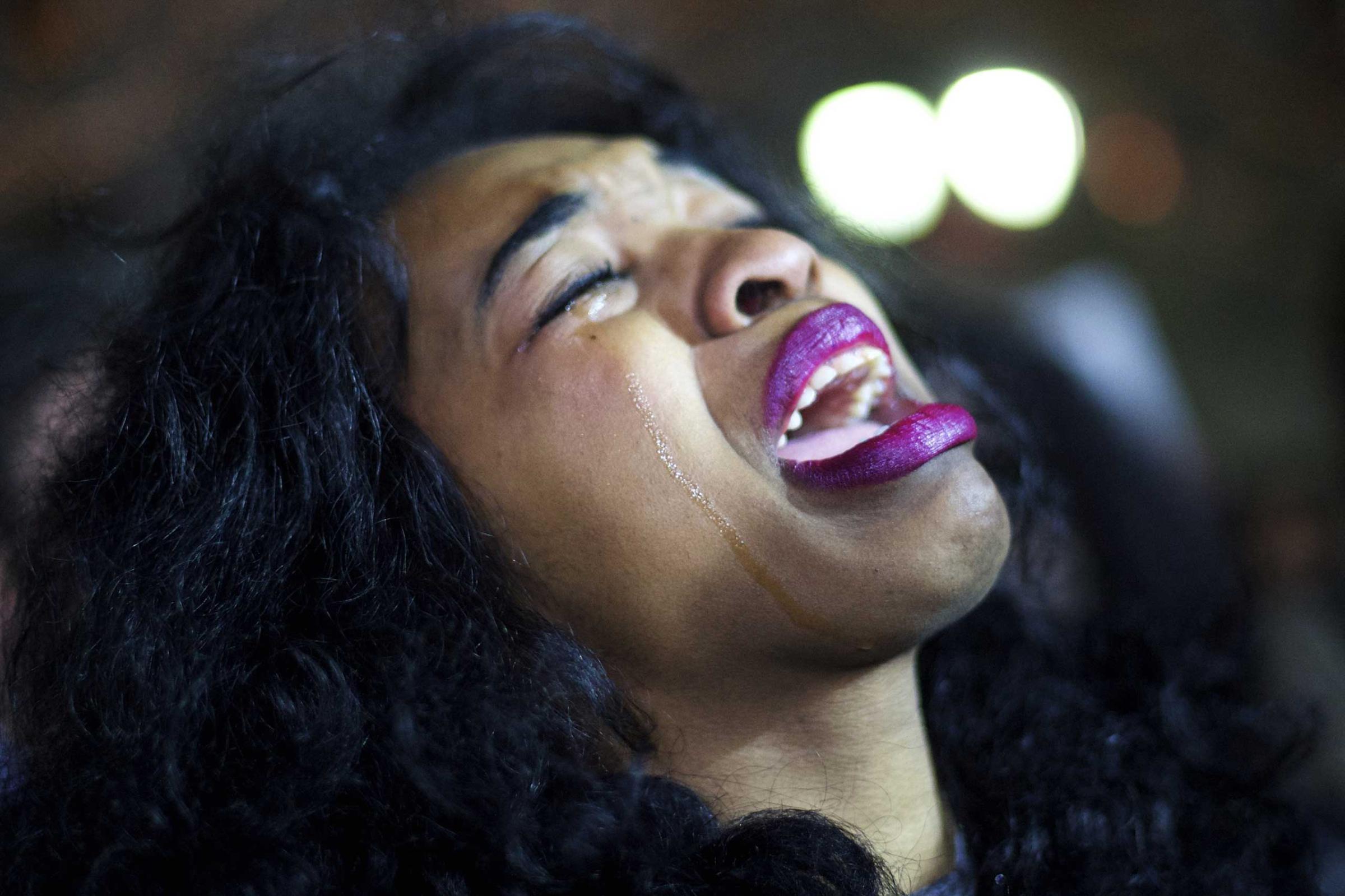

Witness Protesters Taking Over the Streets After the Eric Garner Grand Jury Decision

Holder’s current plans include creating an “institute of justice” that would help continue the dialogue he hopes to undertake over the coming weeks. Holder has been the administration’s point-person on Ferguson response since he visited the troubled city in August following the shooting of an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown.

Holder, who will leave office as soon as his replacement is confirmed, said he believes Ferguson could be a seminal moment for the national conversation about race.

Below is a lightly edited transcript of his Tuesday interview with TIME.

TIME: You said you were encouraged by the peaceful demonstrations after the Ferguson grand jury announcement and you praised the young people who interrupted you on Monday. What do you see in them?

Eric Holder: I think that these protests, if done correctly, can lead to positive change. And I draw distinction between those who protest peacefully in the great tradition of Rosa Parks, for instance.

It’s interesting that I spoke yesterday at the church where Martin Luther King gave some of his famous speeches on the 59th anniversary of Rosa Parks refusing to get up and surrender her seat. And I think if you think about them, that is Rosa Parks, and if you think about Dr. King, and the lasting permanent changes that the movements that they helped to inspire, that he helped to lead, that I think is a guide to the protestors now. I think that protesters, people who feel strongly about the nature of the relationship between law enforcement and communities of color, that if that intensity of feeling is channeled appropriately, then positive change can come.

But it means people have to stay involved. They have to be committed to the cause, they have to organize, they have to do all the things that Rev. [C.T.] Vivian talked about last night in his remarks, that history has shown us produce things that are more than protests: things that morph from protest into a movement.

Do you think this could be a pivotal moment for race relations in this country?

It could be. I think the seeds are there for a movement that could have a very positive impact on that relationship, again, between law enforcement and communities of color. That you could have the basis here for a reexamination of that relationship, for a reforming of that relationship, and an injection of a great deal of trust that does not necessarily exist there now. I think that out of the tragedy that was Michael Brown’s death, some very positive things could happen. That’s could happen, and the question is what is going to happen with all of these people who are at least at this point very committed, very moved by what they have seen, what they are demonstrating. Will these protests coalesce into a movement?

But in direct response to your question, I think yeah, the possibility exists that what we have seen in Ferguson, or that what happened in Ferguson, could be one of those seminal moments that transforms the nation.

You came into office saying this was a “nation of cowards” when it comes to dealing with race, that America has “still not come to grips with its racial past.” What has changed? What hasn’t? Is that still true?

One thing I would urge you to do is read the whole speech. Because I think that quote—it is what it is—but the speech itself I think really, I think accurately reflects what we as a nation have done and tend to do, which is have these incidents and then kind of deal with them in the moment, and then kind of push them aside and real progress is not made.

In the past six years have you laid the groundwork for breaking that cycle?

What I’ve tried to do, among other things at Attorney General, it’s not been the only thing obviously that I’ve done, but I’ve tried to be a force for the kind of positive interaction that I talked about in that speech. With an understanding that raising those concerns is difficult, it’s painful, but I think it’s necessary. Meaningful progress is not made without going through this kind of painful process that I think is necessary and that we, understandably, try to avoid.

You have called U.S. sentencing patterns “shameful” with regards to race. With regards to local law enforcement are there similar patterns of racial discrimination? Has law enforcement got off easy?

I don’t think so. If you look at what we have done with our pattern of practice investigations, I don’t think law enforcement has gotten a pass at all. The number of cases that we have brought shows that our civil rights division has been focused on law enforcement and brought to bear all the tools that we have when we’ve identified problems.

One thing I think we have to be fair about, the fact that we brought record number of cases does not mean that the vast majority of law enforcement officers haven’t conducted themselves in totally appropriate ways. You shouldn’t take from that an indictment of law enforcement writ large. There are certainly problem cities, problem forces. We try to identify them, we try to work with them and change them. The vast majority of law enforcement officers conduct themselves in really honorable appropriate ways.

In August, when the situation in Ferguson was heating up you were in Martha’s Vineyard with the President. Putting yourself back there…What were his initial reactions? Is there anything he said then or the days after to you that stood out?

Without revealing the specifics of conversations, which I just really don’t do with the President, I can certainly say that for those of us up on the Vineyard, we had the feeling there was a potential for a significant reaction to the shooting of Michael Brown. But, I’m not sure that any of us really anticipated that it would—in those initial stages—that it would grow into an issue that was of such searing national concern. It did become obvious, relatively shortly thereafter. But in those first few days, I don’t think—I certainly would not have predicted that it would become an issue of national concern.

Was there a conversation that stood out?

We were talking, while we were up there, about when and if I should go to Ferguson. We knew that that was a significant risk. We didn’t know how people would react. It meant that we were going to have to own this in a way that we didn’t if I didn’t go. So yeah, there were conversations that we had along those lines, and I think the decision made, and I think appropriately so, was that this was something that required high-level federal government involvement—that I needed to go at the behest of the President.

All of this was happening as you were deciding to leave the administration. Did this make you second-guess that?

This is a job that I have loved having. And yeah, there’s probably not a day that I don’t get up and think, “Did I make the right decision?” I’m proud of what we have done. As I said in my resignation remarks, I’m sad about the fact that I will not formally be a part of the ongoing efforts of this administration and this Justice Department.

So, do you plan to continue this in your personal capacity?

I think that I’m certainly going to take some personal time, recharge my batteries, but I do want to be involved in this ongoing work. This whole notion of reconciliation between law enforcement and communities of color is something that I really want to focus on and to do so in a very organized way. Not just as Eric Holder, out there giving speeches—though certainly that could be a part of it—but to have maybe a place where this kind of effort is housed and to be associated with that kind of an entity. That’s the kind of thing I’m beginning to think about.

You announced that the Justice Department will announce new profiling guidance in the coming days. Is that the capstone on your criminal justice reform efforts?

It’s certainly part of a larger effort that I have been involved in dealing with, this whole question of criminal justice reform, whether it is sentencing policies, charging policies, law enforcement deployments. This whole question of the use of race is a part of that overall effort, and it’s a logical, it’s a piece that clearly was missing that hopefully will be filled in by the announcement that we will make in the next couple of days.

How do you respond to criticism that you’ve been able to be more forward about issues of race and discrimination than the President.

I think it’s more of a function of the roles that we play. I’m the Attorney General, and I serve as the head of an organization where a lot of this stuff intersects, where a lot of it comes together. And as a result, it’s more logical, more expected, for me to be more vocal about these issues.

But, I have to say; these are the kinds of issues that I’ve talked about with the President since his first days here in Washington, DC. I met him before he had been sworn in as a senator. We bonded over these criminal justice reform concerns and views of racial matters. We share a worldview, and I am confident there is little that I have said that he would not have agreed with over the past six years.

But again, I am the Attorney General dealing with these issues on a day-to-day basis as part of my job, and so hearing me speak about these issues, in the way you know Robert Kennedy spoke about them as opposed to John Kennedy, I think is kind of the same thing.

People have to also understand that the President has weighed in in a very significant way. You know, you hear from the Attorney General, and it’s significant, there’s no question about that. I have learned, painfully so, that people actually listen to everything that I say. But it’s a different magnitude when the President of the united states comes into the press room and gives some off the cuff remarks, or comes into the press room and reads remarks about these racial matters. So this notion that he has not been heard from in a sufficient way is belied by all the things that he has said, all the things that he has talked about.

In the past few years we’ve seen Republicans embrace elements of criminal justice reform. Do you think there’s an opportunity to make legislative process here?

I think there is the real possibility that this can be a significant area of bipartisan cooperation that would, frankly, be extremely good for this nation: For conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats to get together to put into legislative form the changes that I have used executive authority to do here in the federal system.

I think people come at it form a variety of perspectives. I think one of the things that I don’t think people focus on is that there are some red states that have done some really innovative things when it comes to criminal justice reform, including on rehabilitation, reentry efforts. I think one of the things that we have seen in that regard is that you save money. If you cut down on the rate of recidivism, we’re talking about people not committing crimes, and that necessarily means that people are safer, you’re not spending more money putting people back in jail. I think again that these states have shown, and we are starting to see at the federal level as well, that if you cut back just on the length of a sentence, it will save you really substantial amounts of money. If somebody’s serving two years instead of four, or five years instead of 10, you save a really significant amount of money, and if you invest some of that money into rehabilitative services, reentry services, you can save money and keep the crime rate down. That’s something that I think people intuitively think is illogical. You’re going to spend less money on criminal justice matters and so you’re going to save money and the crime rate’s going to go down. Some people don’t seem to think that makes sense. But the reality is if you spend that money wisely on evidence-based programs, you can do that. And I think that’s what draws people in.

People come to it for their own reasons: cost savings, the whole notion of just fairness, the desire for efficiencies in government, people are drawn to this issue for a variety of reasons, but I think there is a real opportunity there for something very significant to happen in 2015.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com