In the time-honored tradition of governments facing elections, the U.K.’s ruling coalition Wednesday raised taxes on two roundly-hated categories of evil-doers to finance some eye-catching give-aways to prospective voters and distract from its failure to cut the budget deficit as much as it had promised.

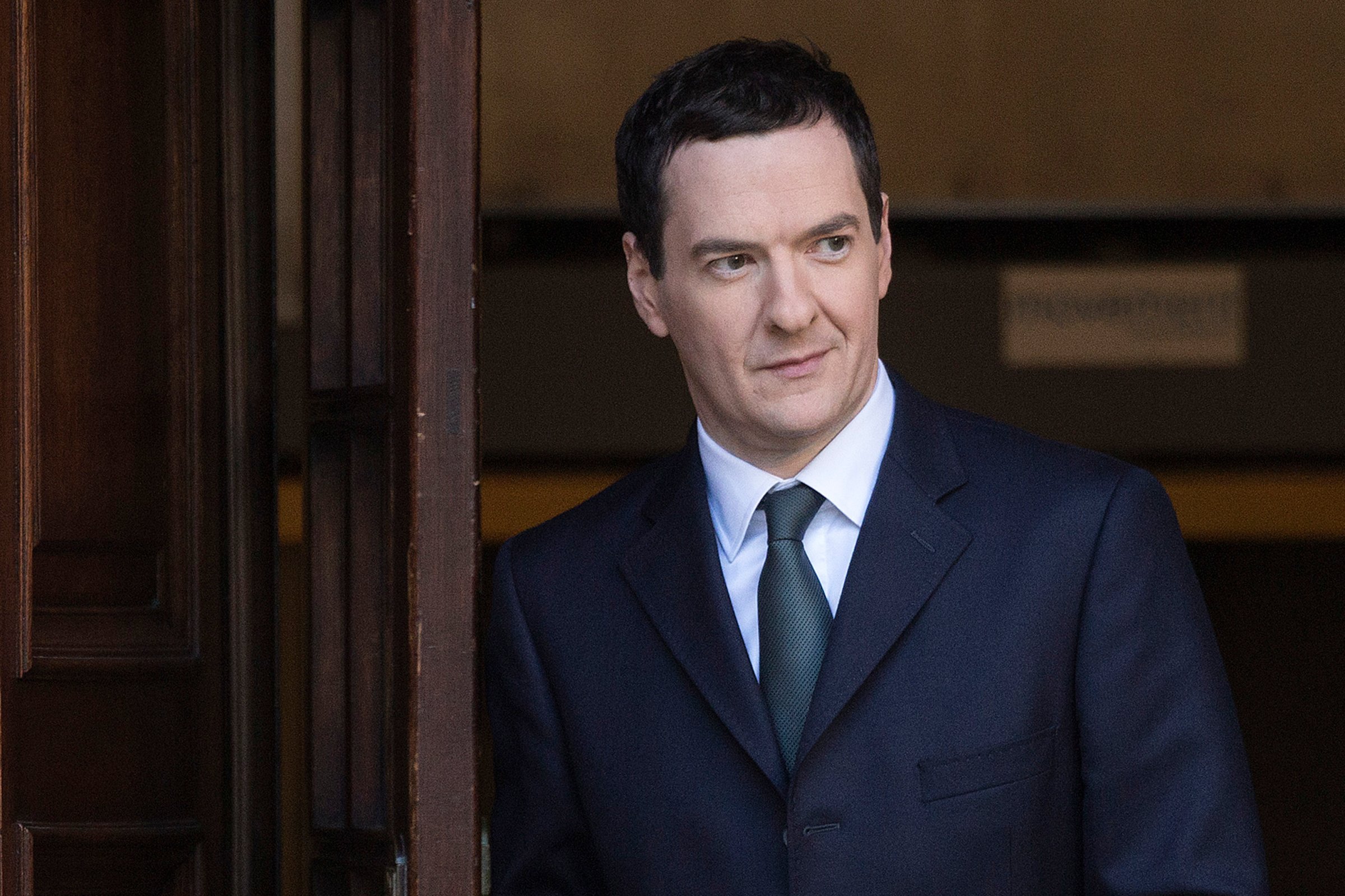

In his ‘Autumn Statement’ to parliament on taxation, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne announced the introduction of what’s commonly known as a “Google Tax” to force multinationals into paying more taxes locally on the profits they earn.

The 25% tax is aimed squarely at tech companies such as Google Inc. and Apple Inc. that have mastered the art of shifting their profits away from the higher-tax markets where they are actually made (such as Britain or Germany) to lower-tax jurisdictions in the E.U. or Caribbean. Such maneuvers generally exploit loopholes in international tax treaties to stay within the letter of the law.

Google notoriously generated more than $18 billion in revenue from the U.K. between 2006-2011, but paid only $16 million in profit taxes, according to Reuters’ analysis of its statutory filings. France’s tax authorities, meanwhile, are currently trying to squeeze up €1 billion ($1.24 billion) in back taxes out of the Mountain View, Ca.-based giant.

Cracking down on tax evasion has become an obsession with European governments since the recession that followed the financial crisis, with treasuries desperate to plug holes in their budgets by any means possible.

They’ve had some success with individuals using tax havens such as Switzerland, but efforts to squeeze more out of companies have been frustrated by the vast scope of the sweetheart deals given by countries such as Luxembourg and Ireland.

Osborne gave no details as to how companies’ liability for the tax would be measured, but said the tax should raise 300 million pounds ($475 million) a year.

That’s still peanuts relative to the scale of the targeted companies’ operations, and it will barely make a dent in the U.K.’s budget deficit which, at 91.6 billion pounds and 5.2% of gross domestic product, is badly overshooting, despite the U.K. having the strongest growth of all the world’s major advanced economies, including the U.S.. The main reason for that, analysts say, is that low productivity and wage growth has damped income tax receipts.

Against that background, Osborne had little room for tax giveaways, and raided that other national bogyeman, the banking sector, to pay for such handouts as were going. Osborne halved the amount of tax relief that banks will be able to claim against their future profits in respect of losses made during the financial crisis, a move that will raise some 4 billion pounds over the next five years.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com