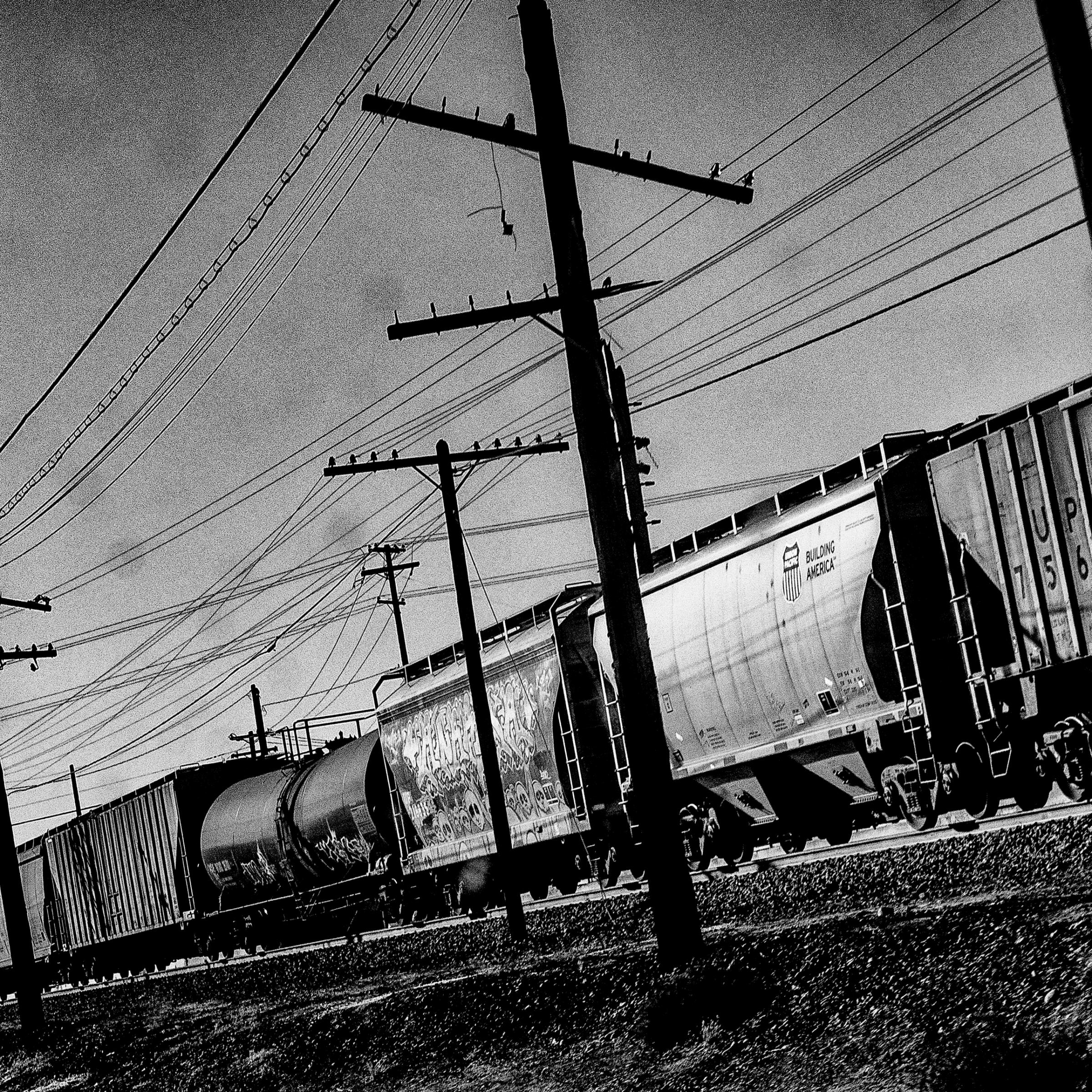

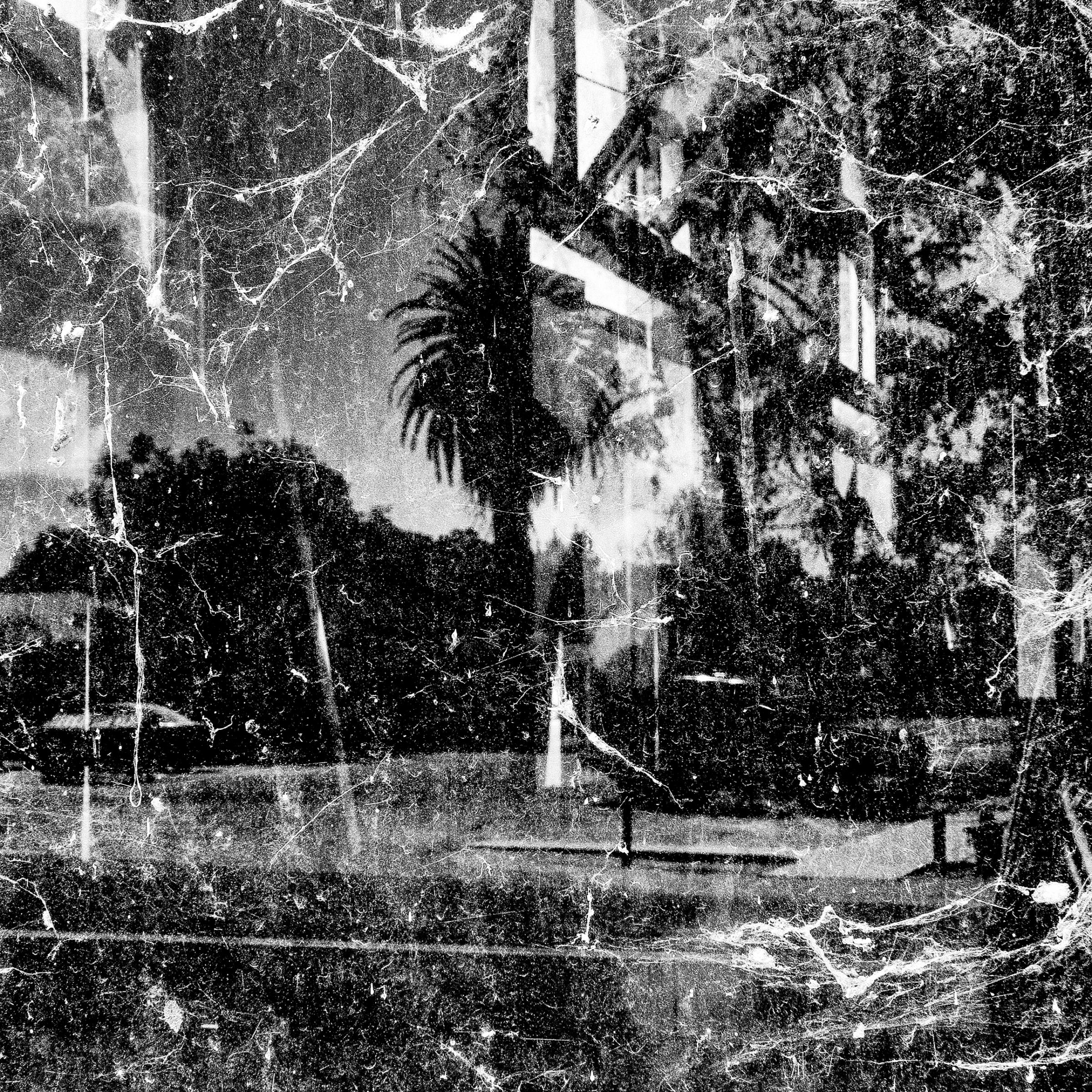

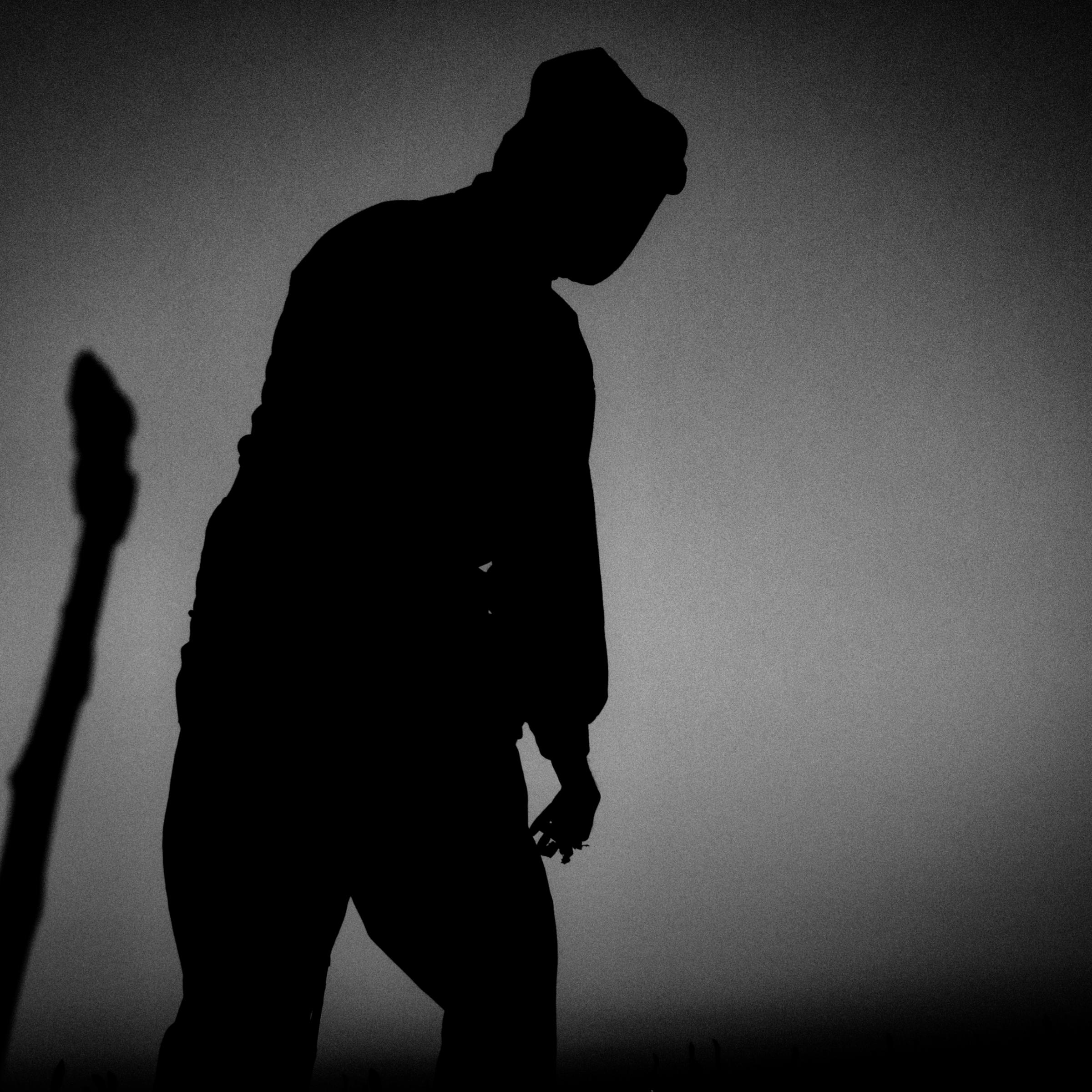

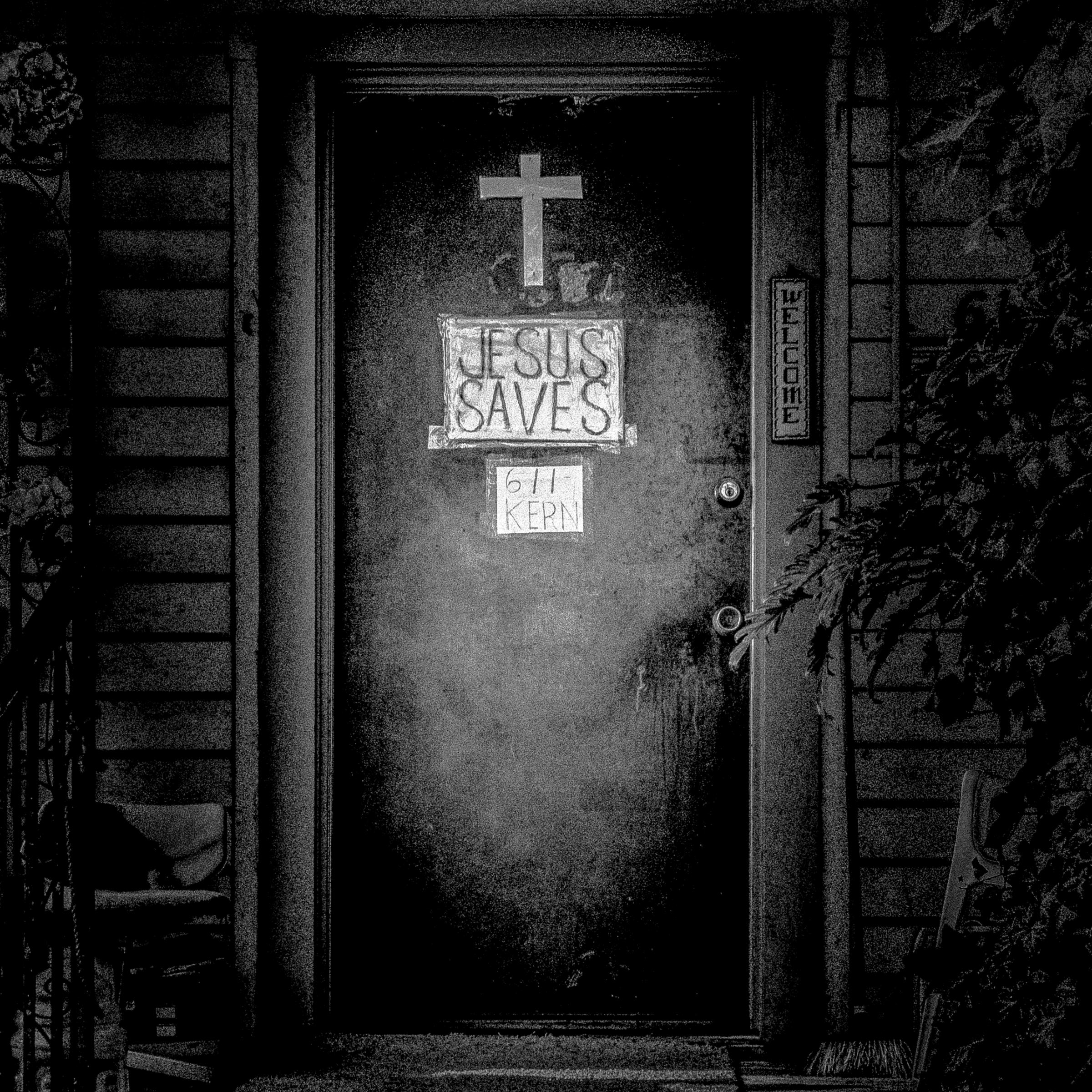

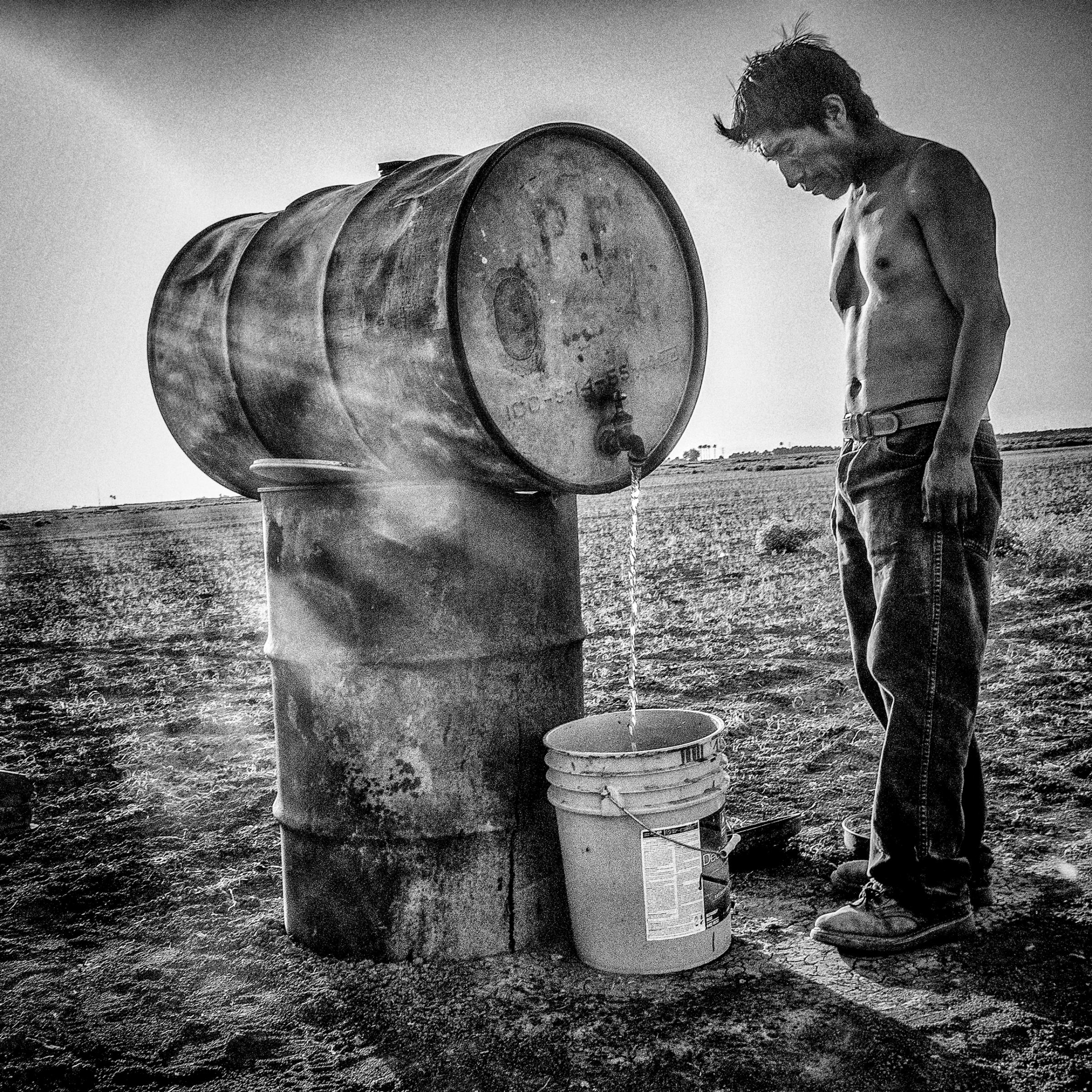

For many of his Instagram followers, Matt Black is a newcomer. He joined the photo-sharing app in December of 2013 to chart, through a series of gritty and deeply personal black-and-white photographs, the physical terrain of economic inequality in his native Central Valley of California, home to three of the five poorest metropolitan areas in the U.S.

“The Central Valley is this kind of vast unknown zone,” Black says. “These towns, these communities are right in the heart of the richest state in the richest country in the world. It’s halfway between Hollywood and Silicon Valley, and yet, you still have conditions like these,” where poor communities are left with bad roads, dirty water, crummy schools and polluted air.

Black’s work might be new to Instagram, but the 44-year-old photographer has spent more than 20 years exploring issues of migration, farming and the environment in the area. That was never his intention, though. “When I first started in photography, my goal was to get out of the Central Valley,” he says. “But it quickly became clear to me that if I had a significant thing to say, it would be about the place I’m from.”

Over 100 years, migration, farm labor and poverty have shaped the region, he says. “These are the places that actually produce what feeds the nation, and the irony is that we’re so dependent on these communities for food and yet rarely do people take time to actually look at them and understand what the challenges are, what these folks are facing — what their lives are like.”

Black’s Geography of Poverty project is designed to address these issues. “People should care because we’re all implicated in this system,” he says. “What we pay at the supermarket is what eventually goes to the farms and goes to the farm laborers. We’re all connected. So, [if] I can lift that veil and make that connection between what we eat, the choices we make, and how that impacts real people — communities — that’s the role I can play.”

Matt Black Is TIME’s Pick for Instagram Photographer of the Year 2014

The best way to do so, Black explains, was by using the unlikeliest of platforms for a photographer who developed his visual identity at a regional newspaper where black-and-white fiber paper prints were the norm.

There’s no doubt that Black is an unconventional choice for Instagram Photographer of the Year. For one thing, he doesn’t always uses an iPhone to shoot the images he posts on his feed – “It’s a mixture of iPhone and a Sony RX 100 camera,” he says, “but it seems like the convention is: if you’re upfront about it, then you’re not cheating, so I’ve been upfront about it.” Second, he’s not a prolific user. In the year since he joined the photo-sharing network, he’s posted 73 images – an average of one photograph every five days. That’s because he doesn’t look at Instagram as a daily journal. “I want each image to contribute and advance this portrait that I’m building, and if I feel like the images that I shot don’t meet that standard, then I don’t publish that day. I’ll wait until the next time.”

For him, Instagram’s appeal resides in its mapping feature – which allows photographers to add geographic coordinates to their images. “Maps are fantastic,” says Black. “They [offer] a complementary augmentation of reality. Photography and maps are similar: they’re born out of the same idea of describing a place for another person to engage with. And, they are right there, together, on that same platform. Without this map, I would not be on Instagram.”

The mapping feature might have attracted Black to Instagram, but the newfound freedom and sense of community is what kept him on the photo-sharing app. “I started Geography of Poverty with 20 followers. I had no clue if people would even understand what this was, and [I didn’t know] whether or not people would want to engage with me over these issues.”

To his surprise, Black found that Instagram users valued substance, engaging with the photographer and his work. “That’s reflected in the comments,” he says. “It’s interesting because in my other work, which are long-term photo essays, I’d spend one or two years trying to tell a story, and people wouldn’t have an opportunity to respond. It was top-down. On Instagram, it’s an unfolding, ongoing narrative, and people engage with that in a new way. It’s something they choose to receive. People take it in. People receive the work in a more intimate way. It’s right there, close to them. You don’t get that same reaction from a gallery show or from a book.”

This, he adds, offers “a fantastic opportunity for photographers to have an independent voice. There are hundreds of millions of people on Instagram wanting to engage with photography. If you’re a photographer working on these issues for so long, how can you not want to reach those people?”

Matt Black is a freelance photographer based in California. Follow him on Instagram @mattblack_blackmatt. In 2013, David Guttenfelder was TIME’s Instagram Photographer of the Year.

Phil Bicker, who edited this photo essay, is a Senior Photo Editor at TIME.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com