Right now, diagnosing disorders like autism relies heavily on interviews and behavioral observations. But new research published in PLoS One shows that a much more objective measure—reading a person’s thoughts through an fMRI brain scan—might be able to diagnose autism with close to perfect accuracy.

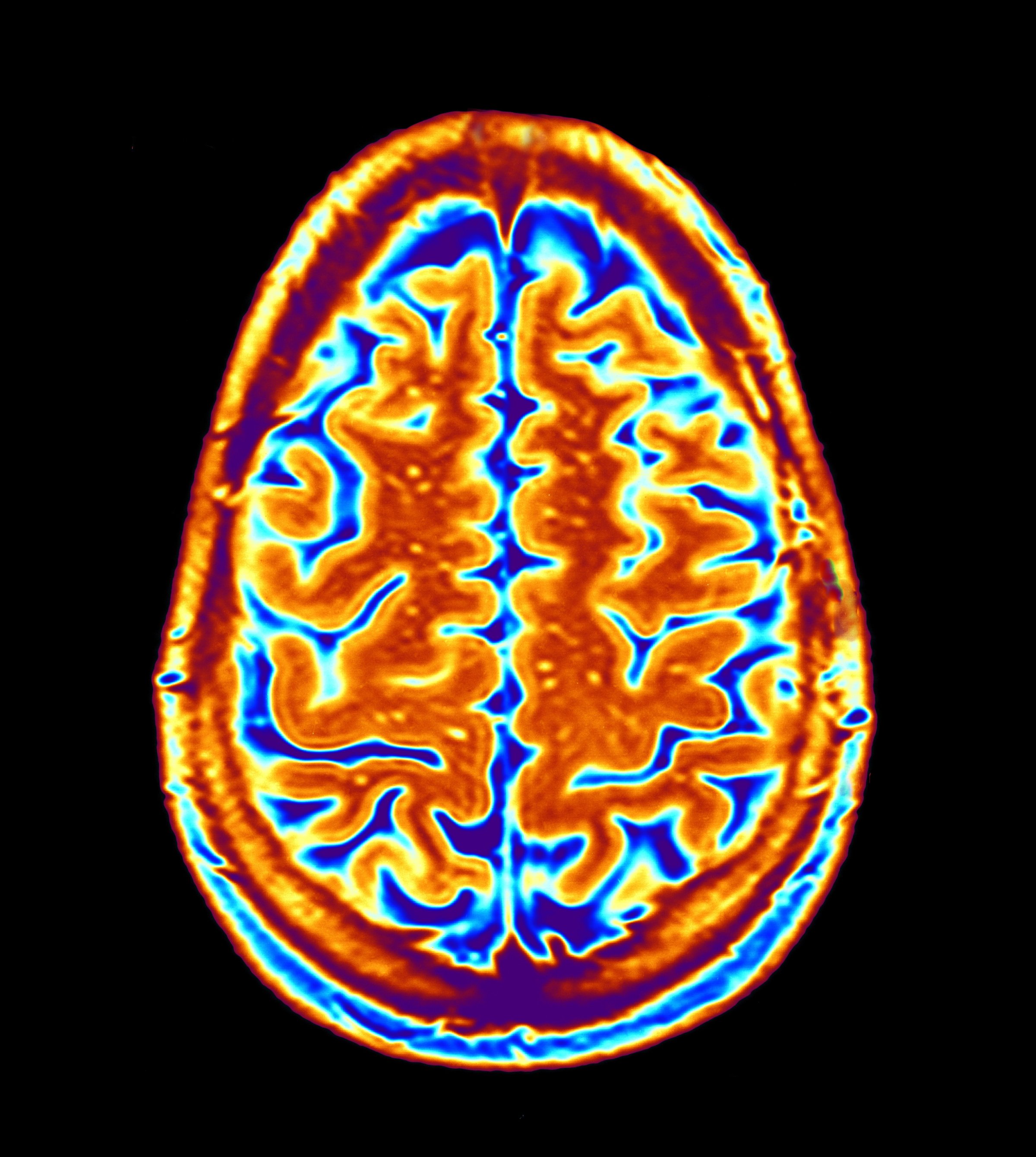

Lead study author Marcel Just, PhD, professor of psychology and director of the Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging at Carnegie Mellon University, and his team performed fMRI scans on 17 young adults with high-functioning autism and 17 people without autism while they thought about a range of different social interactions, like “hug,” “humiliate,” “kick” and “adore.” The researchers used machine-learning techniques to measure the activation in 135 tiny pieces of the brain, each the size of a peppercorn, and analyzed how the activation levels formed a pattern. That pattern, Just says, is amazingly similar across people. “When you think about a house or a chair or a banana while you’re in the scanner, I can tell which one you’re thinking about,” he says.

So great was the difference between the two groups that the researchers could identify whether a brain was autistic or neurotypical in 33 out of 34 of the participants—that’s 97% accuracy—just by looking at a certain fMRI activation pattern. “There was an area associated with the representation of self that did not activate in people with autism,” Just says. “When they thought about hugging or adoring or persuading or hating, they thought about it like somebody watching a play or reading a dictionary definition. They didn’t think of it as it applied to them.” This suggests that in autism, the representation of the self is altered, which researchers have known for many years, Just says. “But this is the first time that anybody’s used that to diagnose autism looking at brain activation.”

Just says his research suggests there could be a new way of diagnosing and understanding certain illnesses and disorders. “If you know what kinds of thoughts are typically disordered in a given psychiatric illness, you could ask a person to think about them and see whether their thoughts are disordered or altered from neurotypical people,” he says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mandy Oaklander at mandy.oaklander@time.com