In December 1950, Jack Kerouac got a letter from his friend Neal Cassady, which recounted a wild weekend in Denver that included climbing out a window to escape the discovery of his affair with a babysitter. According to Kerouac, it was this letter that inspired him to write On the Road in the energetic, disruptive way he did. Also according to Kerouac, this famed epistle had probably been dropped off the side of a houseboat decades ago, never to be held or read ever again.

It turns out Kerouac was, happily, wrong.

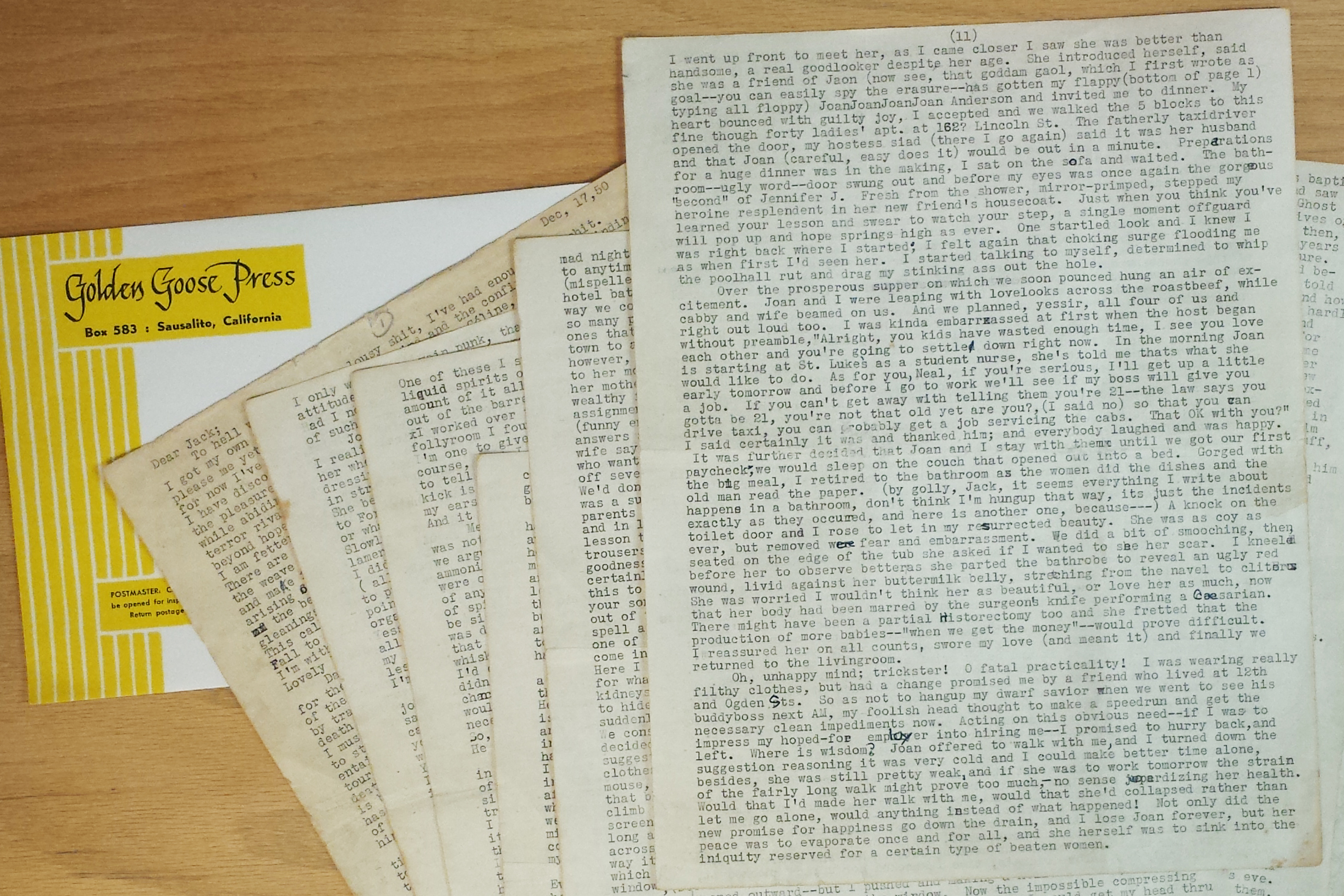

The letter, discovered in Oakland—in a box of forgotten submissions to a publishing house—has been recovered in its entire 18 single-spaced pages. The woman who found the so-called “Joan Anderson letter” is putting it up for auction on Dec. 17, the same day it was dated by Cassady 64 years ago. “I never thought it would be discovered,” says John Tytell, a American literature professor at Queens College. “And it’s a fluke that it was.”

Jean Spinosa, a 41-year-old performance artist based in L.A., lost her father in 2011. Digging through his “hoarder-level” belongings in Oakland the next year, she came across several boxes he had inherited from a now defunct publisher called Golden Goose Press. Her father’s music label had shared a small office with the man who ran Golden Goose, Richard Emerson. One day, she says, Emerson decided to close up shop and announced his intention to throw everything out, including boxes full of unopened poems and letters sent in by hopeful authors.

“He just didn’t care. He was going to throw it in the trash,” Spinosa tells TIME, speaking at the Beat Museum in San Francisco, where the entire letter was displayed on Dec. 1 for the first time since its discovery was made public in November. “And my dad, being a little bit of a hoarder that he was, said ‘Those are poems. Why would you throw out anyone’s poems?’” Emerson told him he was free to keep them, and he did.

The Joan Anderson letter, nicknamed after a girlfriend Cassady writes about in the 16,000-word epistle, was enshrined in history as more than just a letter in 1968. That was the year Kerouac did an interview with the Paris Review and this exchange occurred:

INTERVIEWER

What encouraged you to use the “spontaneous” style of On the Road?

KEROUAC

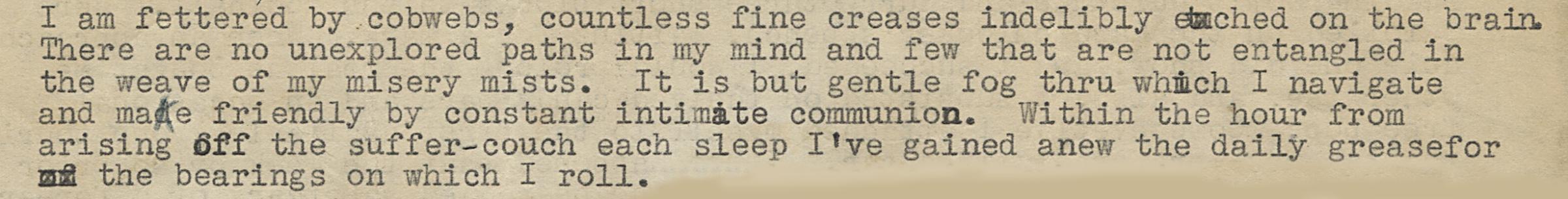

I got the idea for the spontaneous style of On the Road from seeing how good old Neal Cassady wrote his letters to me, all first person, fast, mad, confessional, completely serious, all detailed … The letter, the main letter I mean, was forty thousand words long, mind you, a whole short novel. It was the greatest piece of writing I ever saw, better’n anybody in America, or at least enough to make Melville, Twain, Dreiser, Wolfe, I dunno who, spin in their graves … Neal and I called it, for convenience, the Joan Anderson Letter.

Kerouac goes on to explain that the letter was so great, he lent it to his friend Allen Ginsberg, who then shopped it around to publishers. The first was a man named Gerd Stern, who lived on a houseboat in Sausalito, just to the north of San Francisco. Stern rejected it and, Kerouac imagined in the interview, “This fellow lost the letter: overboard I presume.” What really happened, according to research conducted by Spinosa and the auction house selling the letter, is that Stern gave the letter back to Ginsberg, who then gave it to Emerson for his consideration. “Emerson never read it,” Spinosa says, “and Allen forgot about it.” (Kerouac was also clearly off about the word count.)

The sudden appearance of a long-presumed-dead letter is thrilling for Kerouac obsessors and Beat Generation scholars, who see it as a missing link that may detail how On the Road got made. “I’ve always thought that this letter was crucial to establishing the connection between Neal Cassady’s speech pattern, which was rapid and steeped in the vernacular and unbelievably free, and the source of Kerouac’s inspiration,” Tytell says. “He had broken through to discover something very new, and that letter, that lost letter, I knew was tremendously important.”

About a third of the letter had been copied, presumably by Kerouac, and survived. The rest, left to be imagined, became “mythology” long ago, says Nancy Grace, a professor of English at the College of Wooster in Ohio. “We’ll have to see the letter and see his style in the letter to really be able to tell if it was as influential as the mythology leads us to believe.”

At the Beat Museum in San Francisco, a place where the seats of chairs are ripping and the carpet has some holes, reporters set up their cameras on Monday for a view of the letter arranged in a glass case. Even though they could see the whole pile of pages, the sheets had been arranged to obscure most of the newly rescued words—because, a representative from the auction house explained, while Spinosa owns the letter, the Cassady estate still retains copyright for publishing the work. That will remain true for the buyer who wins the letter later this month.

One hopeful bidder, announced in the midst of the press gathering, is the Beat Museum itself. The largest permanent institution dedicated to the likes of Kerouac and Ginsberg—just blocks from their hallowed City Lights bookstore—started a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for purchasing the letter. “This has to be out in the world,” says Jerry Cimino, who runs the museum and uses phrases like dig this. “This was their stomping grounds.” In the auction, which will be run by Profiles In History, a house that specializes in Hollywood memorabilia, the lot containing the letter will have a reserve price of $300,000.

Regardless of who wins, at least one man will be happy: Gerd Stern, the fellow who had long been blamed, along with Ginsberg, for losing the letter. As soon as Cimino was allowed to share the news that the letter had been discovered, he called his friend Stern, who now lives in New Jersey. “He goes, ‘Wow! Wow! Wow! Wow!’ He must have said it 10 times,” Cimino says. “And he laughed the longest laugh I’ve ever heard.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com