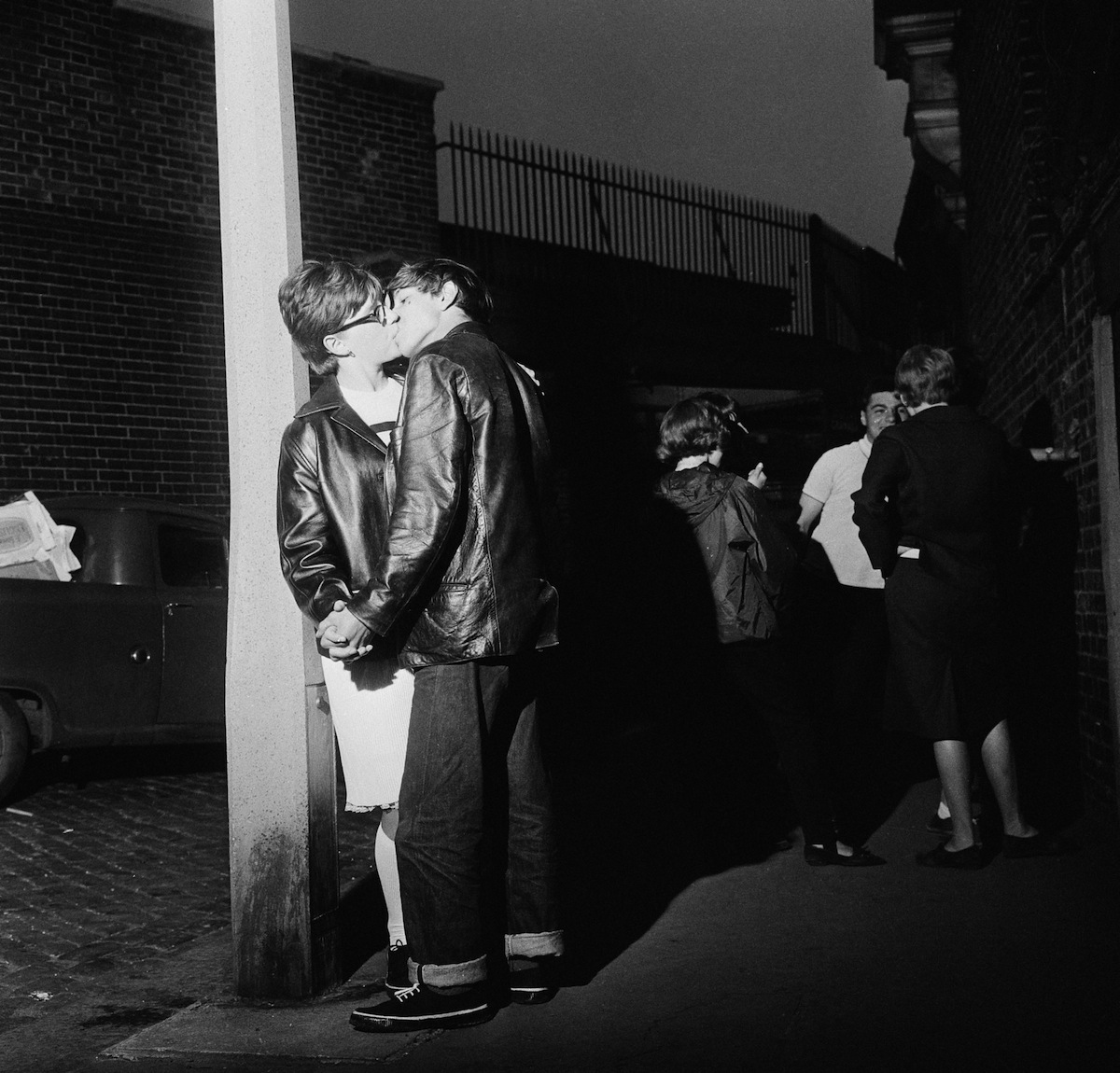

It was January 1964, and America was on the brink of cultural upheaval. In less than a month, the Beatles would land at JFK for the first time, providing an outlet for the hormonal enthusiasms of teenage girls everywhere. The previous spring, Betty Friedan had published The Feminine Mystique, giving voice to the languor of middle-class housewives and kick-starting second-wave feminism in the process. In much of the country, the Pill was still only available to married women, but it had nonetheless become a symbol of a new, freewheeling sexuality.

And in the offices of TIME, at least one writer was none too happy about it. The United States was undergoing an ethical revolution, the magazine argued in an un-bylined 5000-word cover essay, which had left young people morally at sea.

The article depicted a nation awash in sex: in its pop music and on the Broadway stage, in the literature of writers like Norman Mailer and Henry Miller, and in the look-but-don’t-touch boudoir of the Playboy Club, which had opened four years earlier. “Greeks who have grown up with the memory of Aphrodite can only gape at the American goddess, silken and seminude, in a million advertisements,” the magazine declared.

But of greatest concern was the “revolution of [social] mores” the article described, which meant that sexual morality, once fixed and overbearing, was now “private and relative” – a matter of individual interpretation. Sex was no longer a source of consternation but a cause for celebration; its presence not what made a person morally suspect, but rather its absence.

The essay may have been published half a century ago, but the concerns it raises continue to loom large in American culture today. TIME’s 1964 fears about the long-term psychological effects of sex in popular culture (“no one can really calculate the effect this exposure is having on individual lives and minds”) mirror today’s concerns about the impacts of internet pornography and Miley Cyrus videos. Its descriptions of “champagne parties for teenagers” and “padded brassieres for twelve-year-olds” could have been lifted from any number of contemporary articles on the sexualization of children.

We can see the early traces of the late-2000s panic about “hook-up culture” in its observations about the rise of premarital sex on college campuses. Even the legal furors it details feel surprisingly contemporary. The 1964 story references the arrest of a Cleveland mother for giving information about birth control to “her delinquent daughter.” In September 2014, a Pennsylvania mother was sentenced to a minimum of 9 months in prison for illegally purchasing her 16-year-old daughter prescription medication to terminate an unwanted pregnancy.

But what feels most modern about the essay is its conviction that while the rebellions of the past were necessary and courageous, today’s social changes have gone a bridge too far. The 1964 editorial was titled “The Second Sexual Revolution” — a nod to the social upheavals that had transpired 40 years previously, in the devastating wake of the First World War, “when flaming youth buried the Victorian era and anointed itself as the Jazz Age.” Back then, TIME argued, young people had something truly oppressive to rise up against. The rebels of the 1960s, on the other hand, had only the “tattered remnants” of a moral code to defy. “In the 1920s, to praise sexual freedom was still outrageous,” the magazine opined, “today sex is simply no longer shocking.”

Today, the sexual revolutionaries of the 1960s are typically portrayed as brave and daring, and their predecessors in the 1920s forgotten. But the overarching story of an oppressive past and a debauched, out-of-control present has remained consistent. As Australian newspaper The Age warned in 2009: “[m]any teenagers and young adults have turned the free-sex mantra of the 1970s into a lifestyle, and older generations simply don’t have a clue.”

The truth is that the past is neither as neutered, nor the present as sensationalistic, as the stories we tell ourselves about each of them suggest. Contrary to the famous Philip Larkin poem, premarital sex did not begin in 1963. The “revolution” that we now associate with the late 1960s and early 1970s was more an incremental evolution: set in motion as much by the publication of Marie Stopes’s Married Love in 1918, or the discovery that penicillin could be used to treat syphilis in 1943, as it was by the FDA’s approval of the Pill in 1960. The 1950s weren’t as buttoned up as we like to think, and nor was the decade that followed them a “free love” free-for-all.

Similarly, the sex lives of today’s teenagers and twentysomethings are not all that different from those of their Gen Xer and Boomer parents. A study published in The Journal of Sex Research this year found that although young people today are more likely to have sex with a casual date, stranger or friend than their counterparts 30 years ago were, they do not have any more sexual partners — or for that matter, more sex — than their parents did.

This is not to say that the world is still exactly as it was in 1964. If moralists then were troubled by the emergence of what they called “permissiveness with affection” — that is, the belief that love excused premarital sex – such concerns now seem amusingly old-fashioned. Love is no longer a prerequisite for sexual intimacy; and nor, for that matter, is intimacy a prerequisite for sex. For people born after 1980, the most important sexual ethic is not about how or with whom you have sex, but open-mindedness. As one young man amongst the hundreds I interviewed for my forthcoming book on contemporary sexual politics, a 32-year-old call-center worker from London, put it, “Nothing should be seen as alien, or looked down upon as wrong.”

But America hasn’t transformed into the “sex-affirming culture” TIME predicted it would half a century ago, either. Today, just as in 1964, sex is all over our TV screens, in our literature and infused in the rhythms of popular music. A rich sex life is both a necessity and a fashion accessory, promoted as the key to good health, psychological vitality and robust intimate relationships. But sex also continues to be seen as a sinful and corrupting force: a view that is visible in the ongoing ideological battles over abortion and birth control, the discourses of abstinence education, and the treatment of survivors of rape and sexual assault.

If the sexual revolutionaries of the 1960s made a mistake, it was in assuming that these two ideas – that sex is the origin of all sin, and that it is the source of human transcendence – were inherently opposed, and that one could be overcome by pursuing the other. The “second sexual revolution” was more than just a change in sexual behavior. It was a shift in ideology: a rejection of a cultural order in which all kinds of sex were had (un-wed pregnancies were on the rise decades before the advent of the Pill), but the only type of sex it was acceptable to have was married, missionary and between a man and a woman. If this was oppression, it followed that doing the reverse — that is to say, having lots of sex, in lots of different ways, with whomever you liked — would be freedom.

But today’s twentysomethings aren’t just distinguished by their ethic of openmindedness. They also have a different take on what constitutes sexual freedom; one that reflects the new social rules and regulations that their parents and grandparents unintentionally helped to shape.

Millennials are mad about slut-shaming, homophobia and rape culture, yes. But they are also critical of the notion that being sexually liberated means having a certain type — and amount — of sex. “There is still this view that having sex is an achievement in some way,” observes Courtney, a 22-year-old digital media strategist living in Washington DC. “But I don’t want to just be sex-positive. I want to be ‘good sex’-positive.” And for Courtney, that means resisting the temptation to have sex she doesn’t want, even it having it would make her seem (and feel) more progressive.

Back in 1964, TIME observed a similar contradiction in the battle for sexual freedom, noting that although the new ethic had alleviated some of pressure to abstain from sex, the “competitive compulsion to prove oneself an acceptable sexual machine” had created a new kind of sexual guilt: the guilt of not being sexual enough.

For all our claims of openmindedness, both forms of anxiety are still alive and well today – and that’s not just a function of either excess or repression. It’s a consequence of a contradiction we are yet to find a way to resolve, and which lies at the heart of sexual regulation in our culture: the sense that sex can be the best thing or the worst thing, but it is always important, always significant, and always central to who we are.

It’s a contradiction we could still stand to challenge today, and doing so might just be key to our ultimate liberation.

Rachel Hills is a New York-based journalist who writes on gender, culture, and the politics of everyday life. Her first book, The Sex Myth: The Gap Between Our Fantasies and Reality, will be published by Simon & Schuster in 2015.

Read next: How I Learned About Sex

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com