Here’s a difficult one, history buffs: Who was Harry Truman? I know, I know, I told you it would be tough, but think hard: Some famous general? Maybe a physicist?

If you guessed U.S. president, good for you! And if you also knew that Truman was the one who came right after Roosevelt (Franklin, that is) and right before Eisenhower, go to the head of the class.

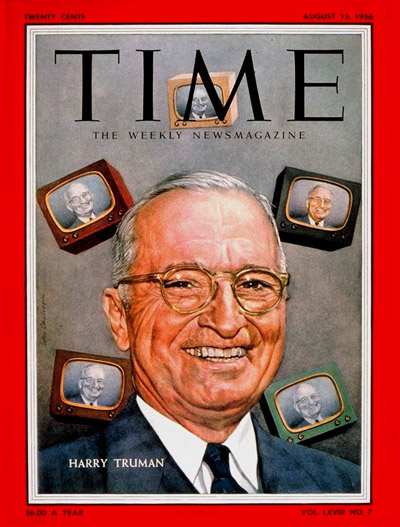

OK, so maybe remembering Truman isn’t such a big deal. But here’s the thing: By 2040, according to a new study just published in Science, only 26% of college students will remember to include his name if they are asked to make a list of all U.S. Presidents, regardless of order.

That finding, which is less a function of historical illiteracy than of the mysterious ways the human brain works, reveals a lot about the perishability of memory. And that, in turn, has implications for contemporary dramas like the Ferguson tragedy, the Bill Cosby mess and the very underpinnings of the criminal justice system.

The Science study, conducted by a pair of psychologists at Washington University in St. Louis, was actually four studies that took place over 40 years—in 1974, 1991, 2009 and 2014. In the first three, the investigators asked groups of then-college students to list all of the presidents in the order in which they served, and also to list as many of them as they could by name regardless of where they fell in history.

In all three groups over all three eras, the results were remarkably similar. As a rule, 100% of respondents knew the president currently serving, and virtually all knew the prior one or two. Performance then fell off with each previous presidency. Roughly 75% of students in 1974 placed FDR in the right spot, for example. Fewer than 20% of Millennials—born much later—could do that. In all groups, the historical trail would go effectively cold one or two presidents before the subjects’ birth—falling into single digits.

There were exceptions. The Founding Father presidents, particularly the first three—George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson—scored high in all groups. As did Abraham Lincoln and his two immediate successors, Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant. As for the Tylers and Taylors and Fillmores? Forget about them—which most people did. The pattern held again in a single larger survey conducted in 2014, with a mixed-age sample group that included Boomers, Gen X’ers and Millennials, all performing true to their own eras.

Almost none of this had to do with any one President’s historical relevance—apart from the Founding Fathers and Lincoln. James Polk’s enormously consequential, one-term presidency is far less recalled than, say, Jimmy Carter’s much less successful four-year stint. Instead, our memory is personal, a thing of the moment, and deeply fallible—and that means trouble.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the Ferguson drama is the mix of wildly different stories eyewitnesses presented to the grand jury, with Michael Brown portrayed as anything from anger-crazed aggressor to supine victim. Some witnesses may have been led by prosecutors, some may have simply been making things up, but at least some were surely doing their best, trying to remember the details of a lethal scene as it unfolded in a few vivid seconds.

If forensic psychology has shown anything, it’s that every single expectation or bias a witness brings to an experience—to say nothing of all of the noise and press and controversy that may follow—can contaminate recall until it’s little more reliable than that of someone who wan’t there at all.

Something less deadly—if no less ugly—applies in the Bill Cosby case. In an otherwise reasonable piece in the Nov. 25 Washington Post, columnist Kathleen Parker cautions against a collective rush to judgment and reminds readers that under the American legal system, Cosby is not a rapist, but an alleged rapist; and his victims, similarly, are as yet only alleged victims. Fair enough; that’s what the criminal justice rules say. But then, there’s this:

“…we have formed our opinions… only on the memories of the women, most of whom say they were drugged at the time. Some of them have conceded that their recollections are foggy—which, of course they would be, after decades and under pharmaceutically induced circumstances, allegedly.”

In other words, if Cosby did drug them, then perhaps we must throw their testimony out of court because, um, Cosby drugged them. Talk about the (alleged) criminal making hay on his crime. And yet, when it comes to the science of memory, that’s an argument that could work before a judge.

Finally, too, there is the unseemly business of Ray Rice. Virtually nobody who knows what he did has forgotten it—which is what happens when you’re a massively strong athlete and you cold-cock a woman. But it was the complete elevator video actually showing the blow, as opposed to the earlier one in which Rice was seen merely dragging the unconscious body of his soon-to-be-wife out into a hotel hallway, that spelled his end—at least until his lifetime NFL ban was overturned on Nov. 28. Knowing what happened is very different from seeing what happened—and once you saw the savagery of Rice’s blow, you could never unsee it.

When it comes to presidents, the fallibility of memory can help. In the years immediately following Richard Nixon’s resignation, it was a lot harder to appreciate his manifest triumphs—the Clean Air Act, the opening to China—than it is now. George W. Bush is enjoying his own small historical rebound, with his AIDS in Africa initiative and his compassionate attempt at immigration reform looking better and better in the rear-view mirror—despite the still-recent debacles of his Presidency.

We do ourselves a disservice if we hold historical grudges against even our most flawed presidents; but we do just as much harm if we allow ourselves to forget why ill-planned land wars in countries like Iraq or cheap break-ins at places like the Watergate are so morally criminal. Forget the sequence of the Presidents if you must, but do remember their deeds.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com