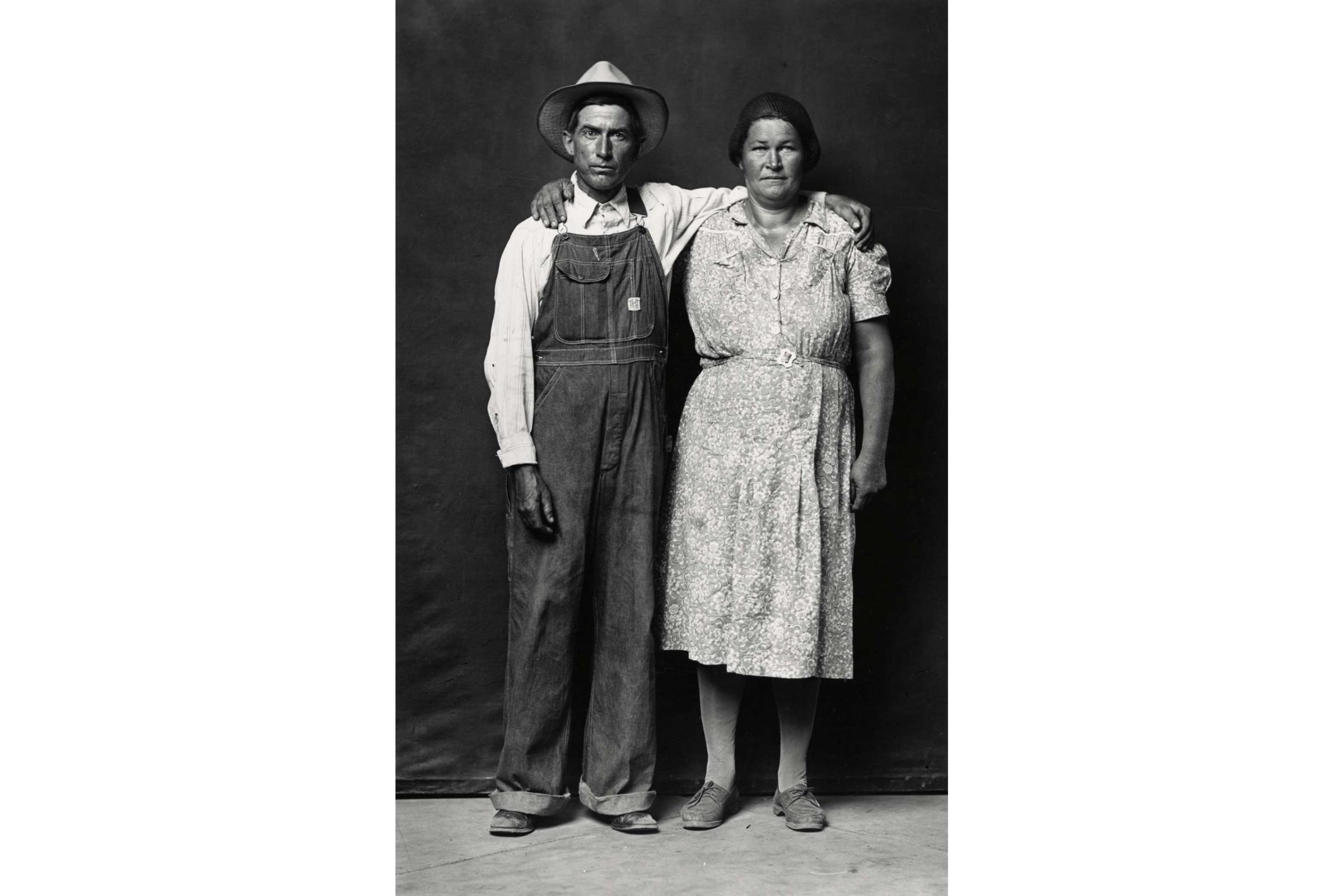

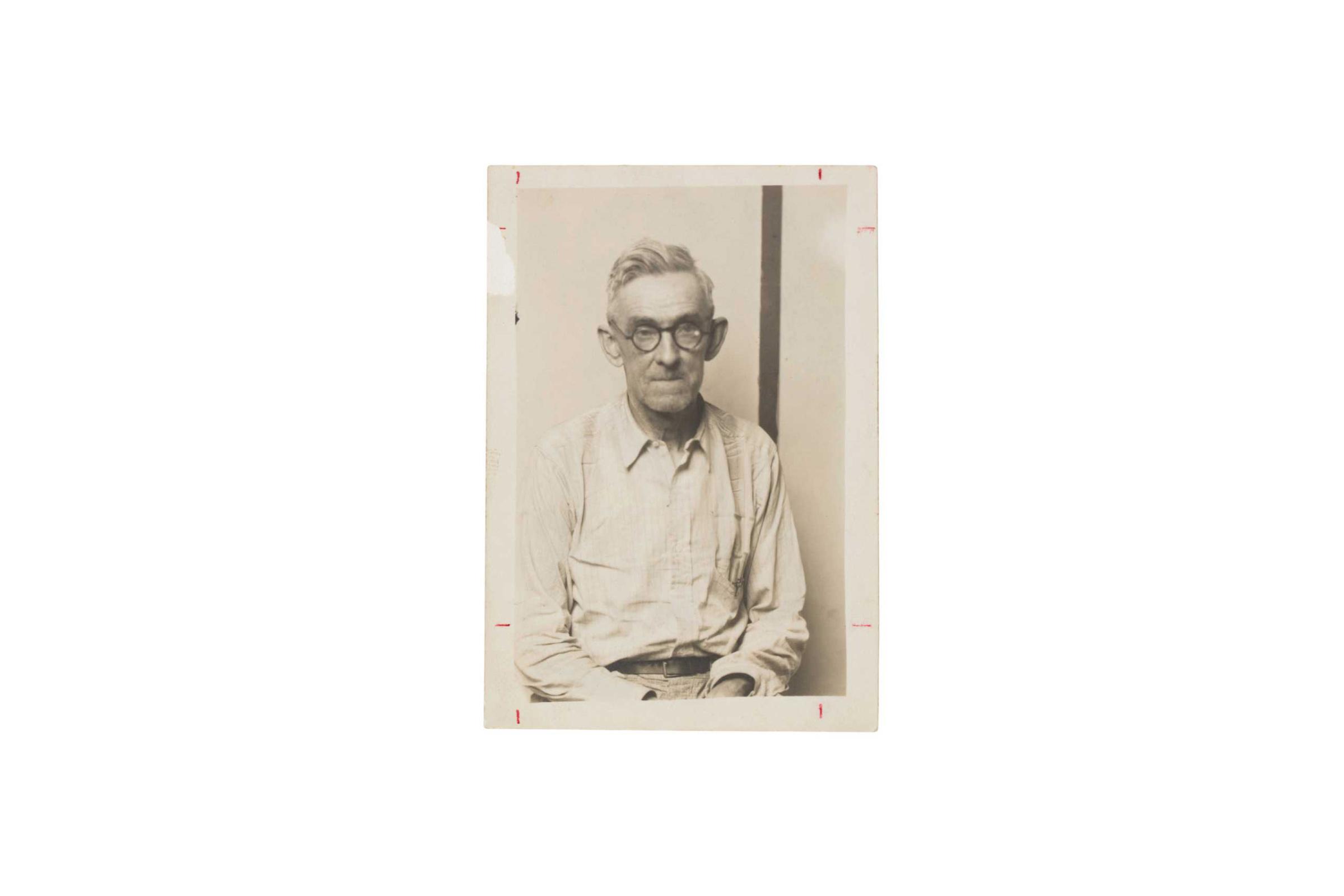

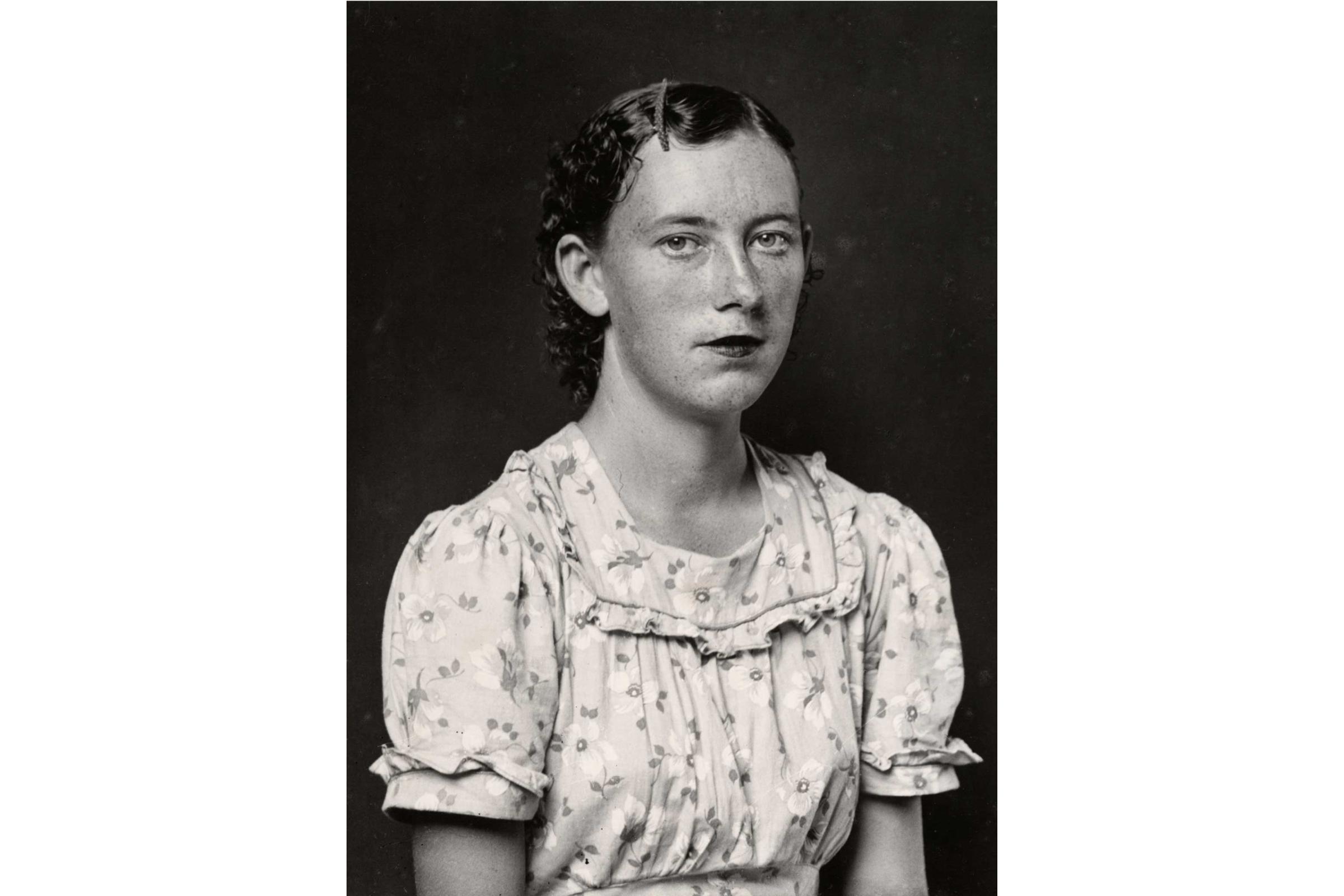

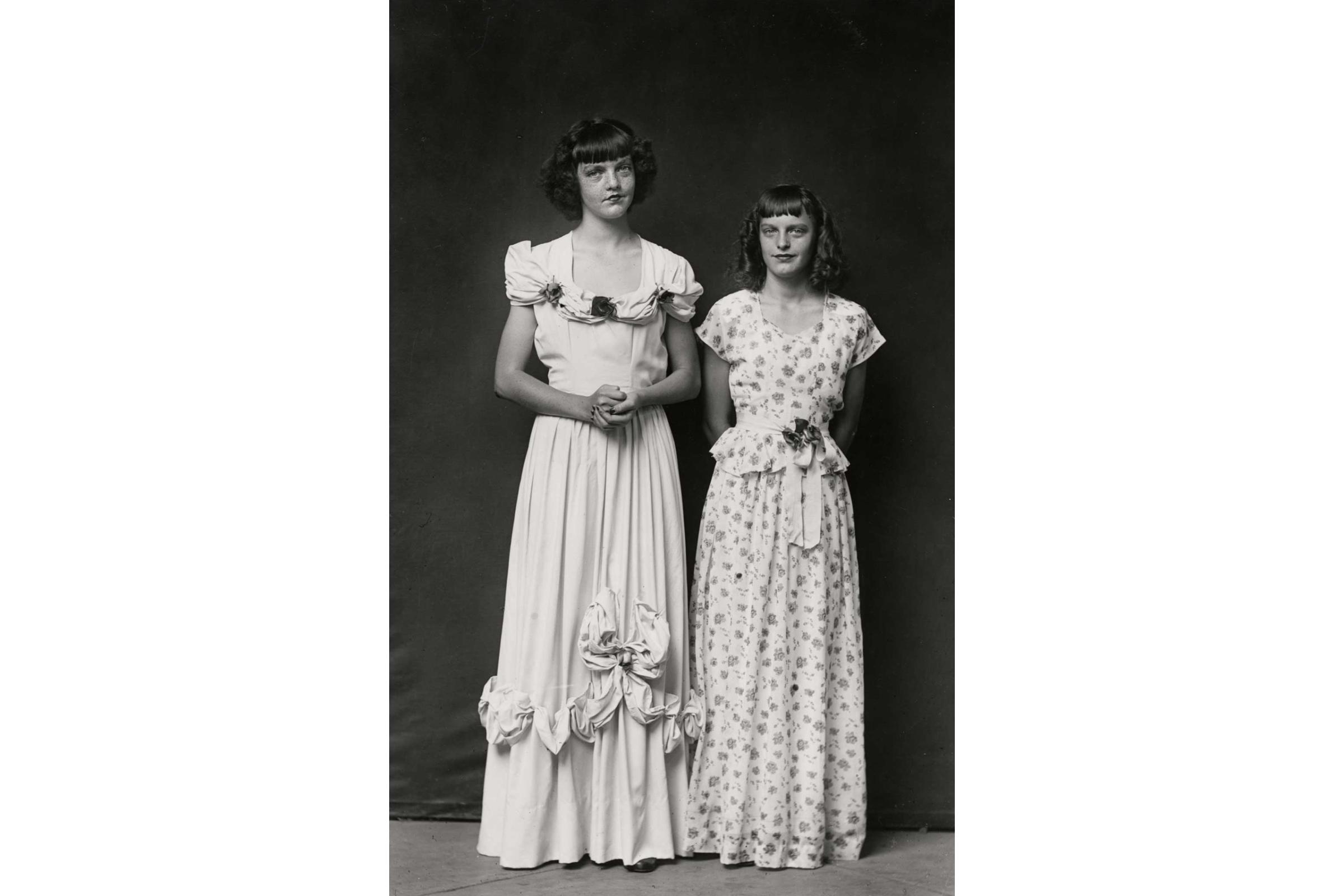

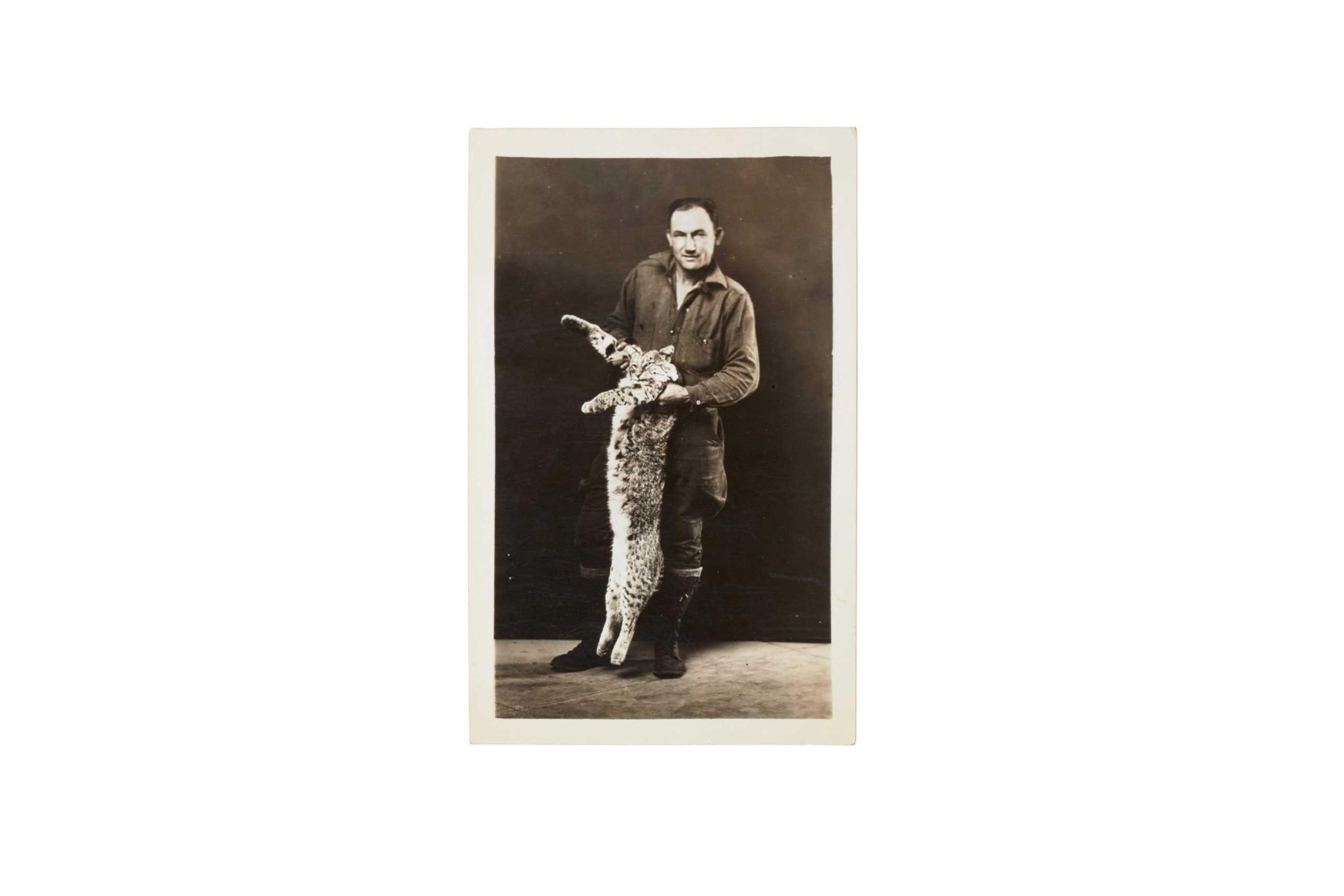

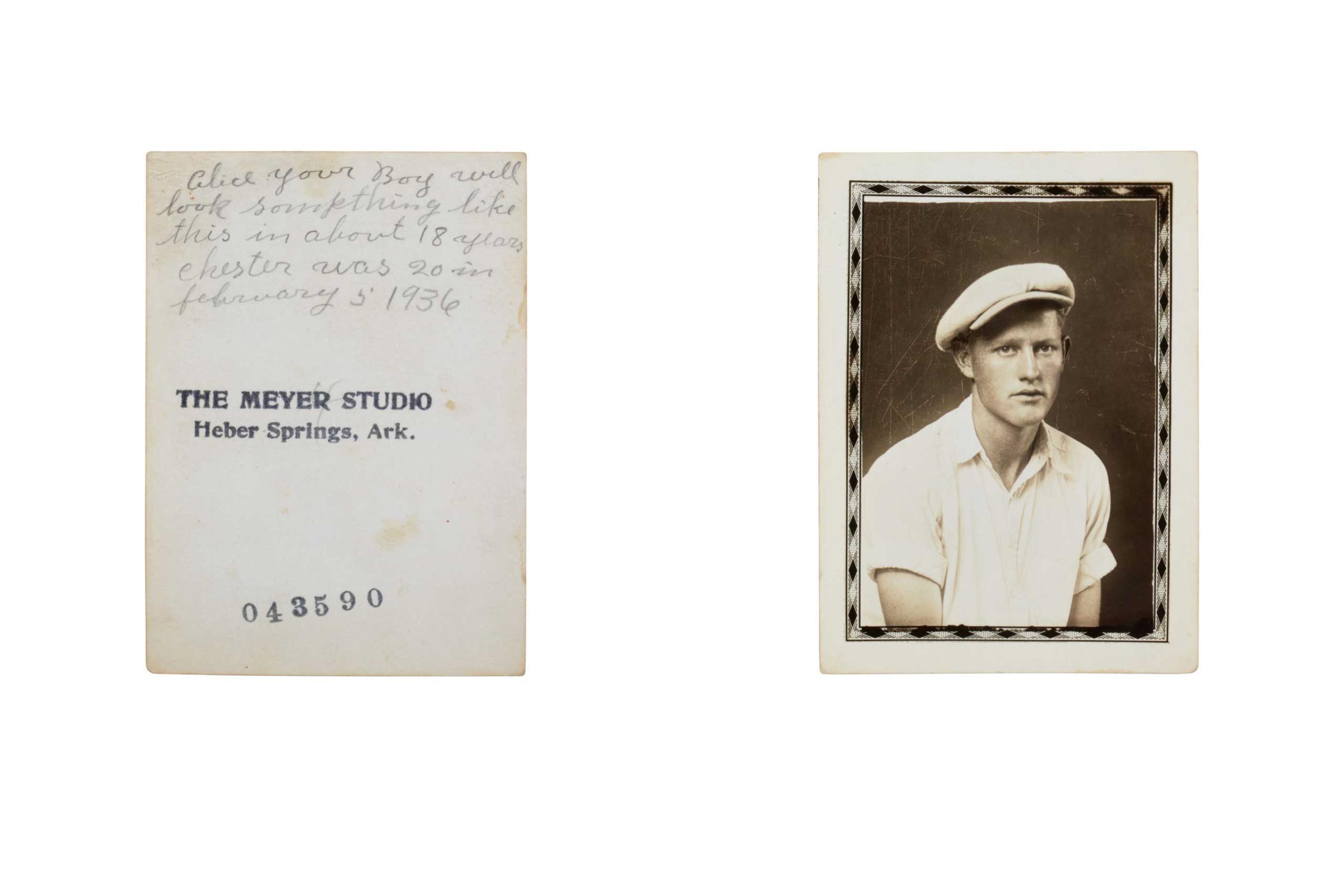

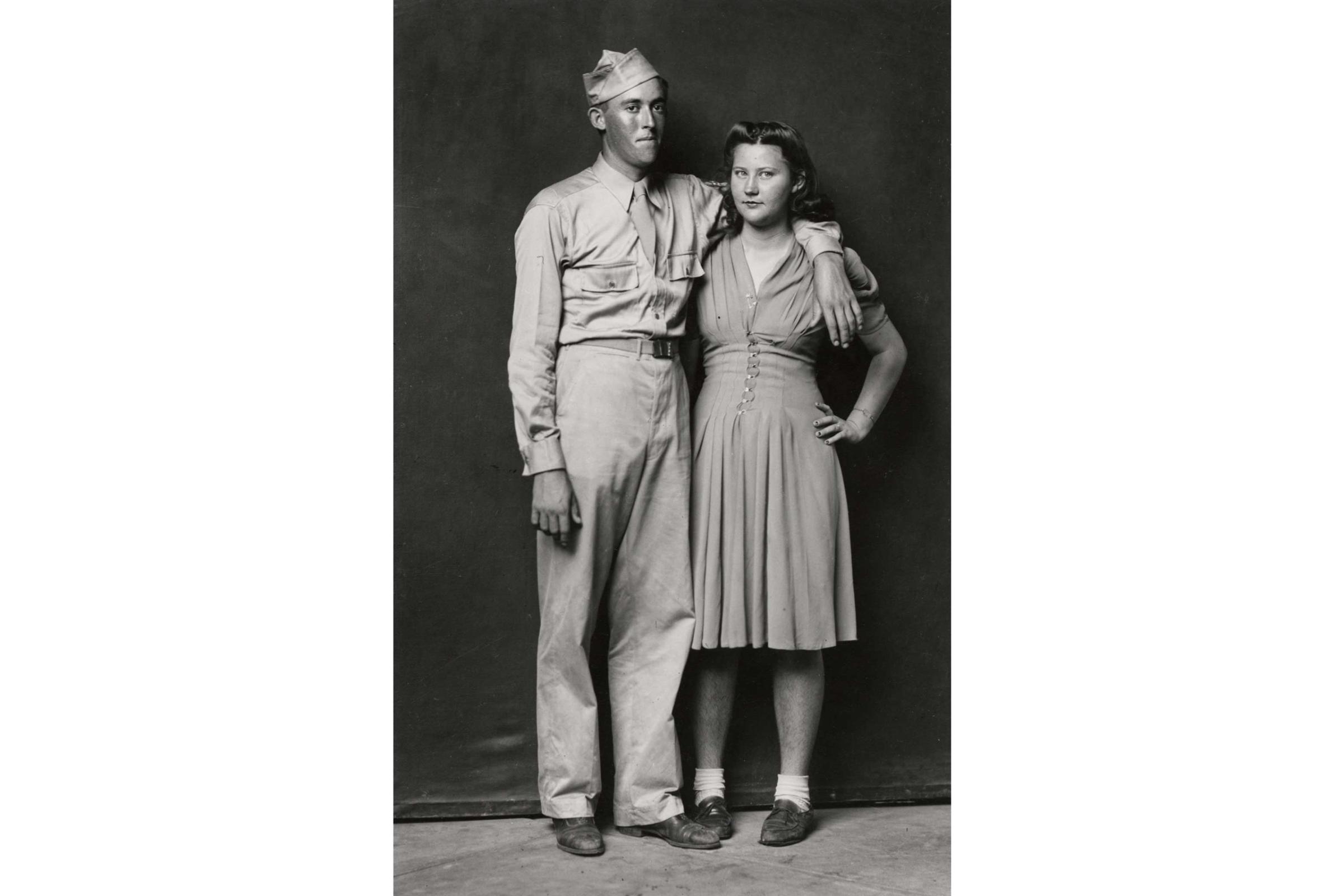

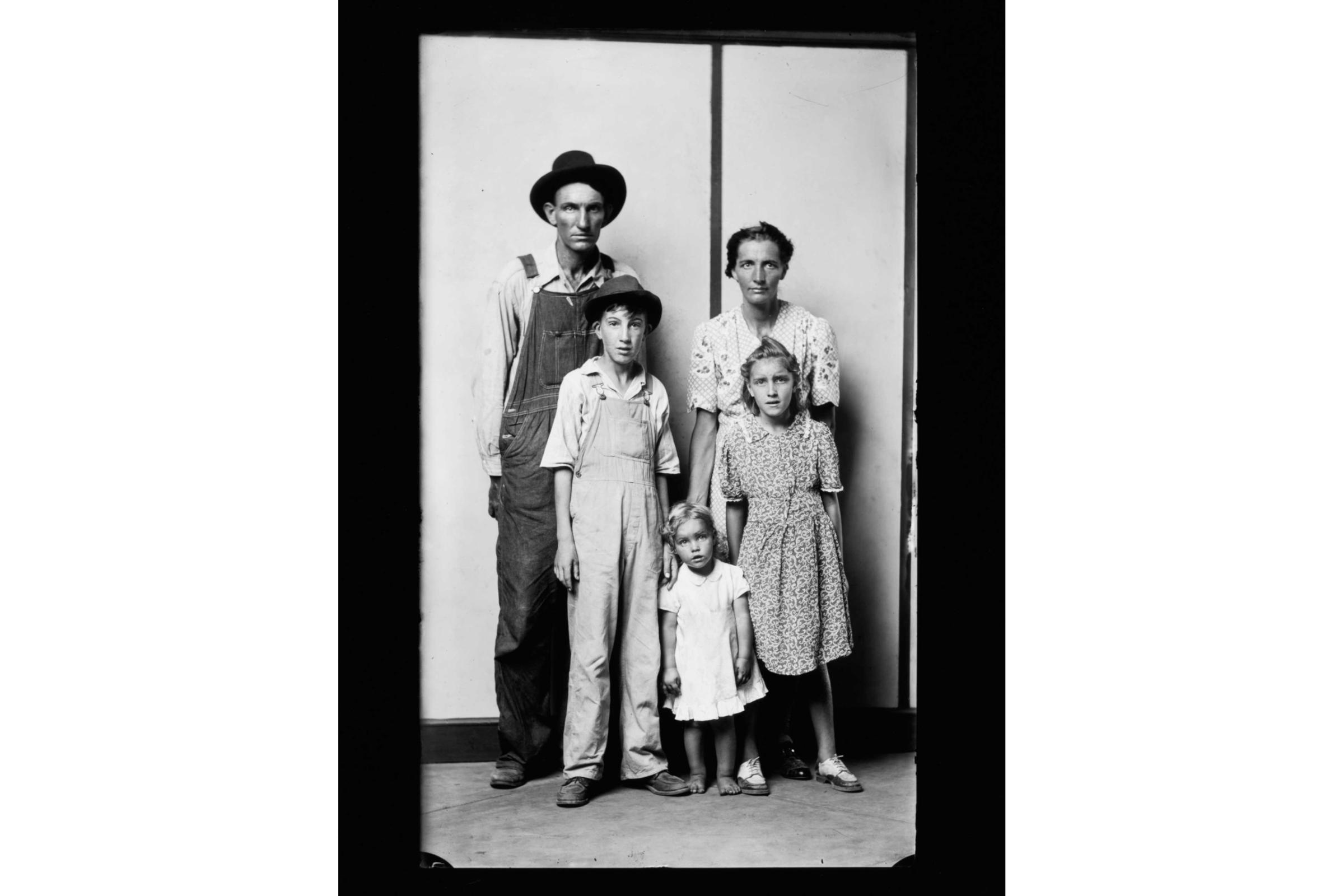

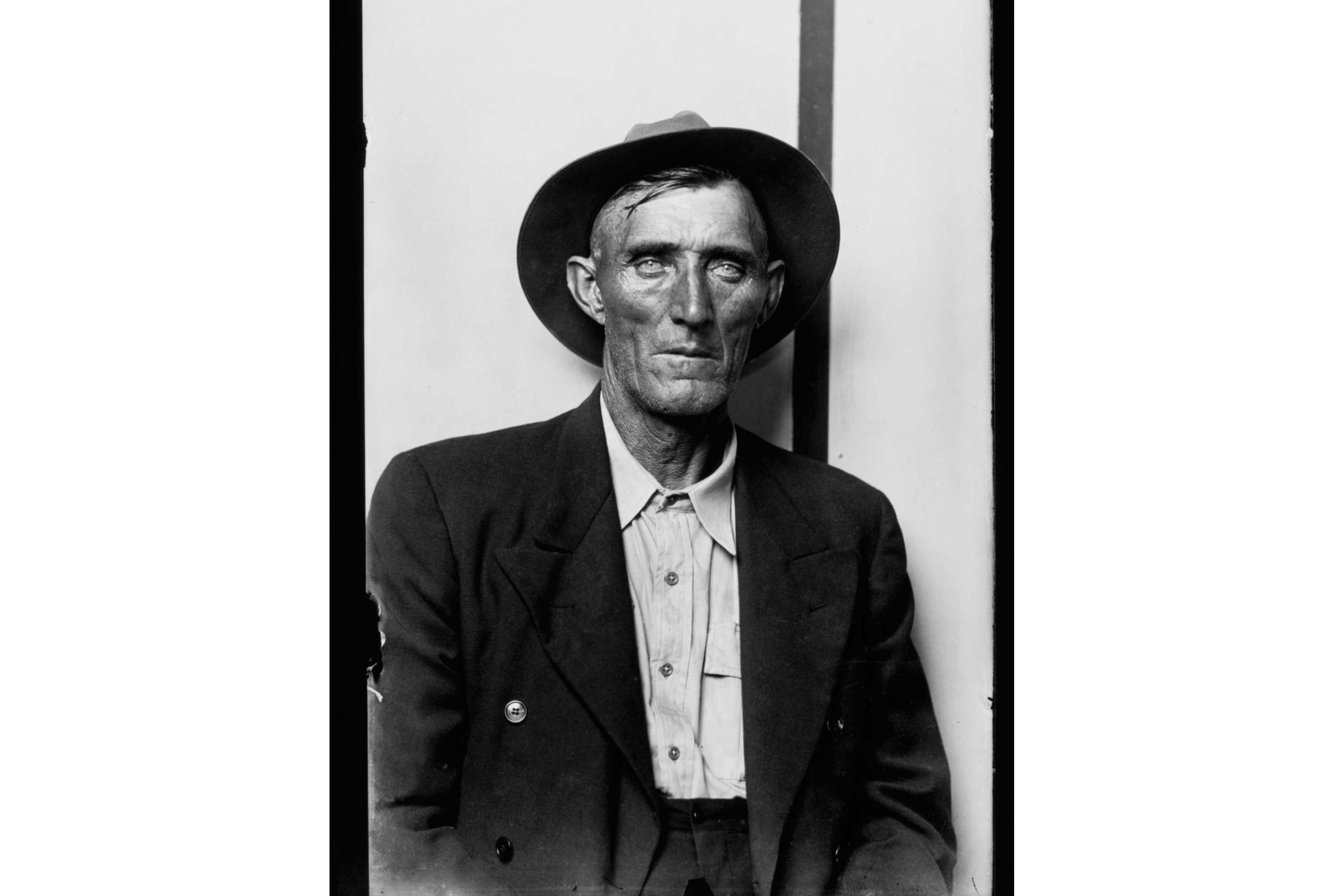

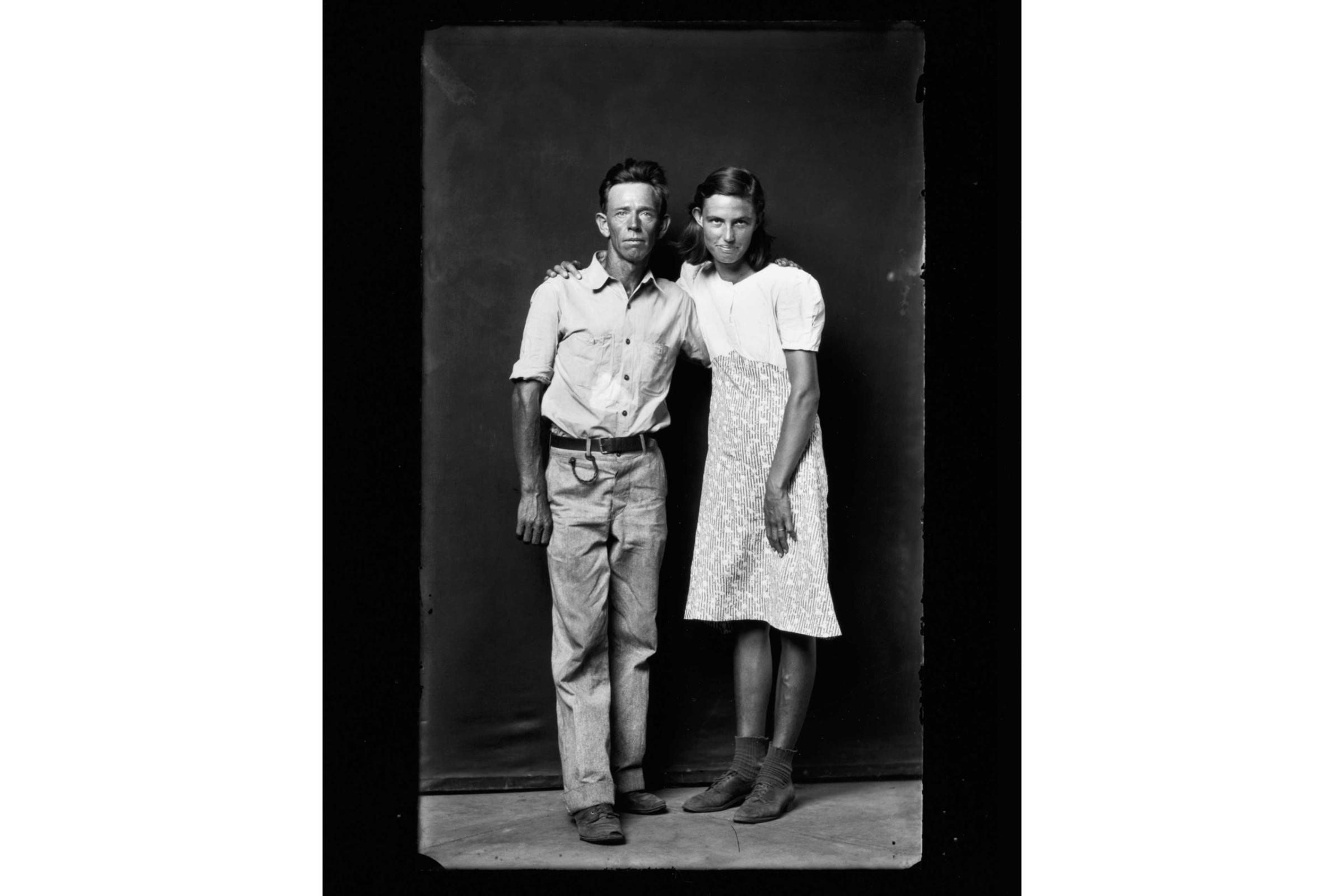

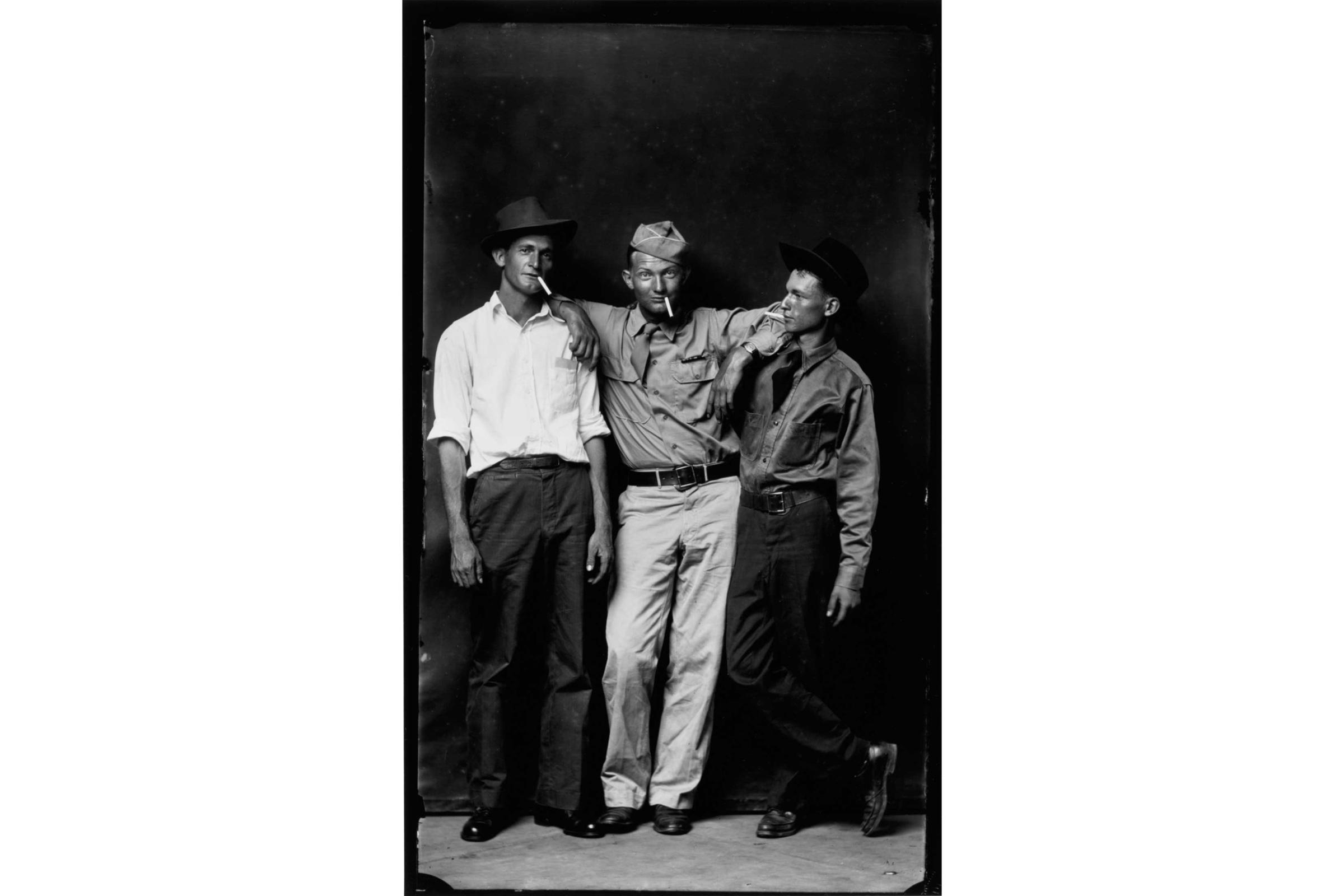

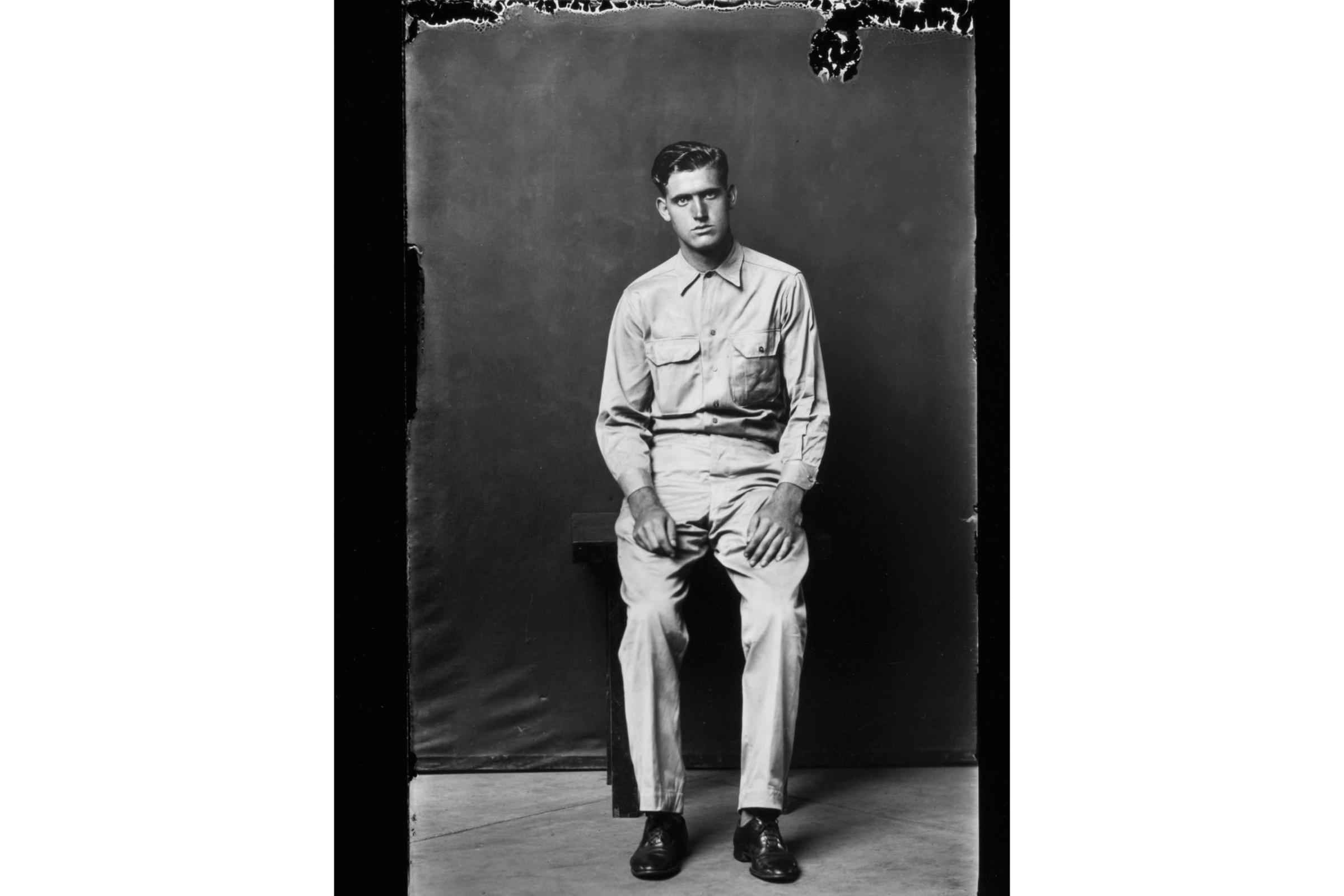

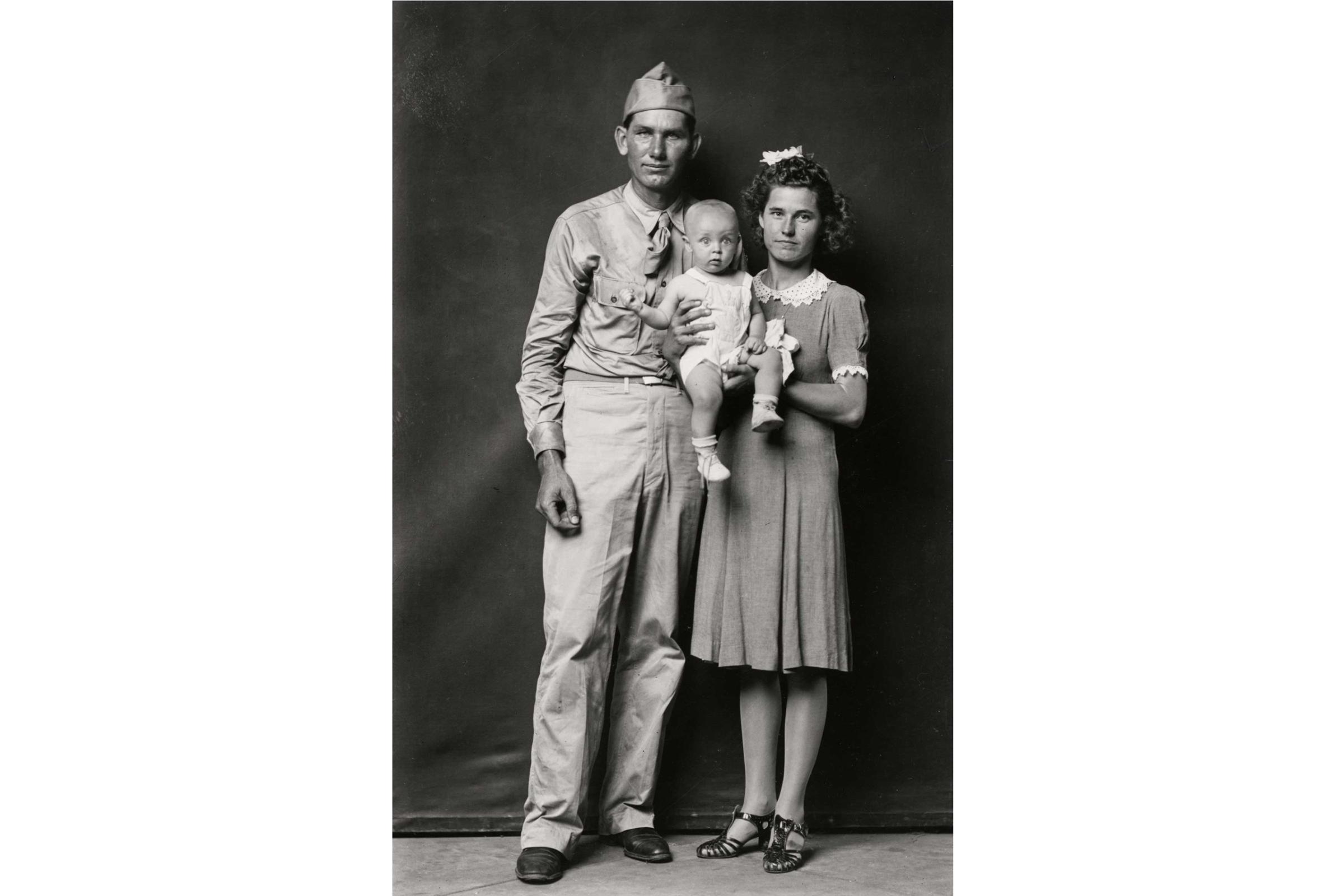

Mike Disfarmer was a commercial photographer working in Heber Springs, a small town in rural Arkansas since the 1910s. He took portraits of residents for pennies in the photo studio where he lived alone until his death in 1959.

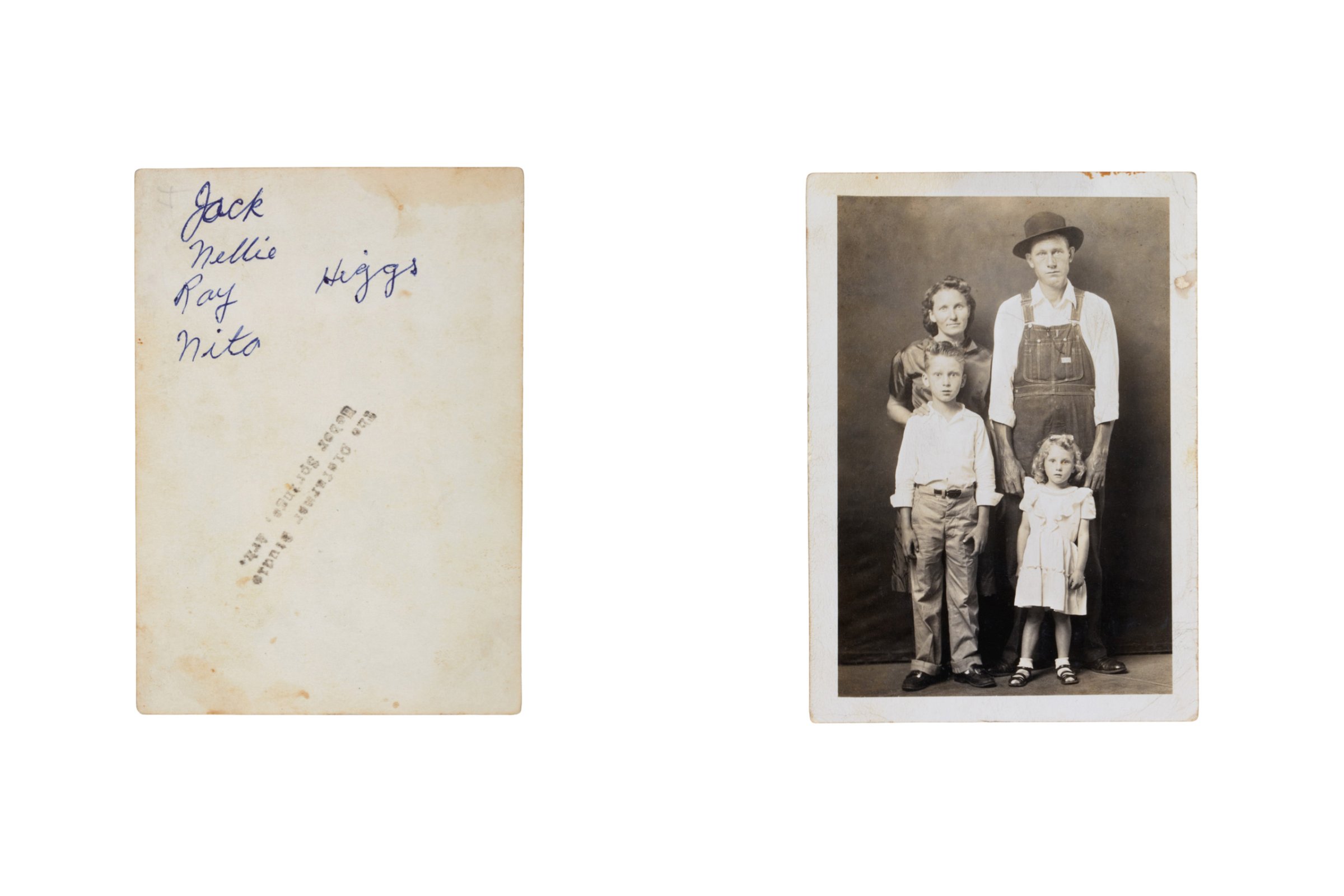

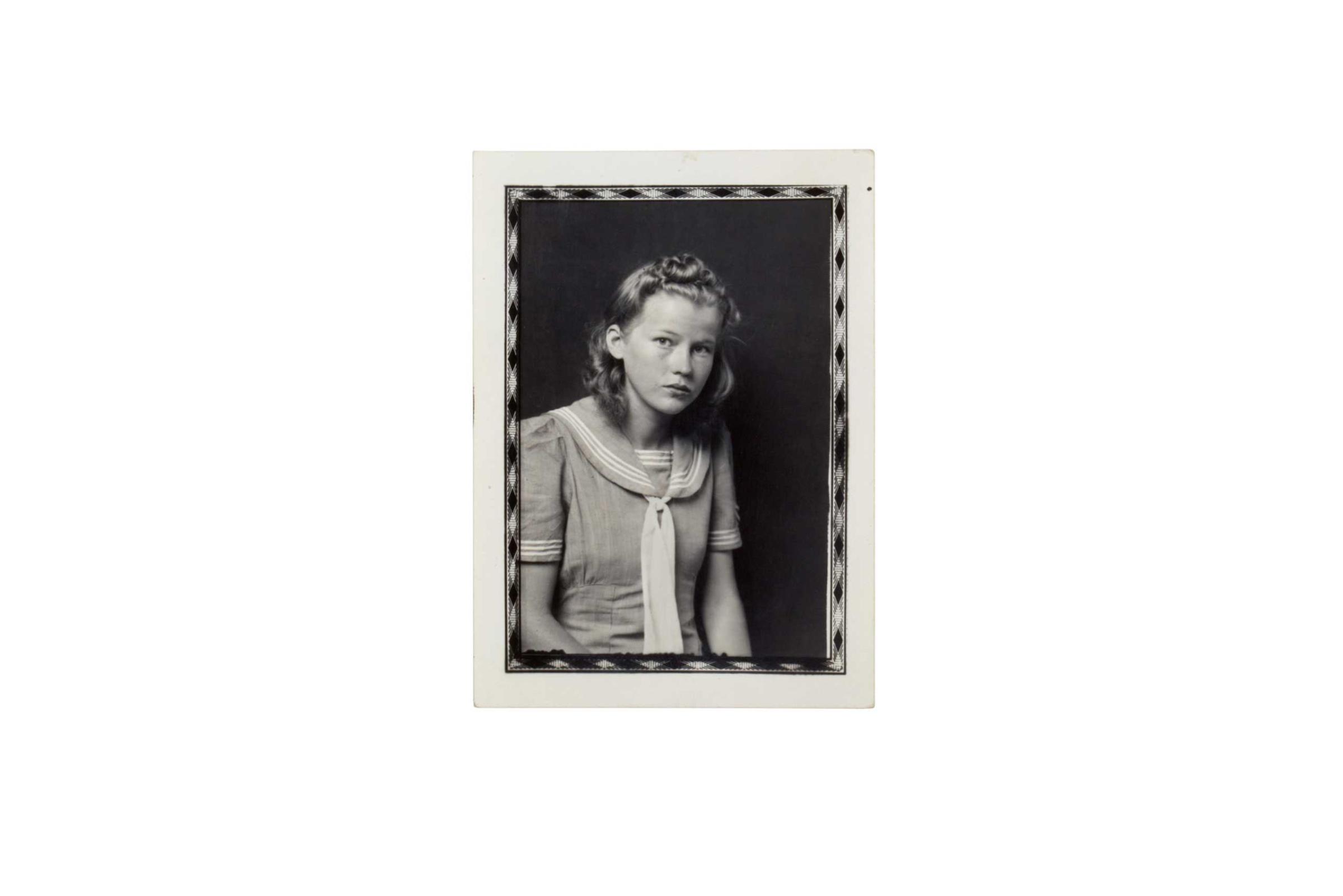

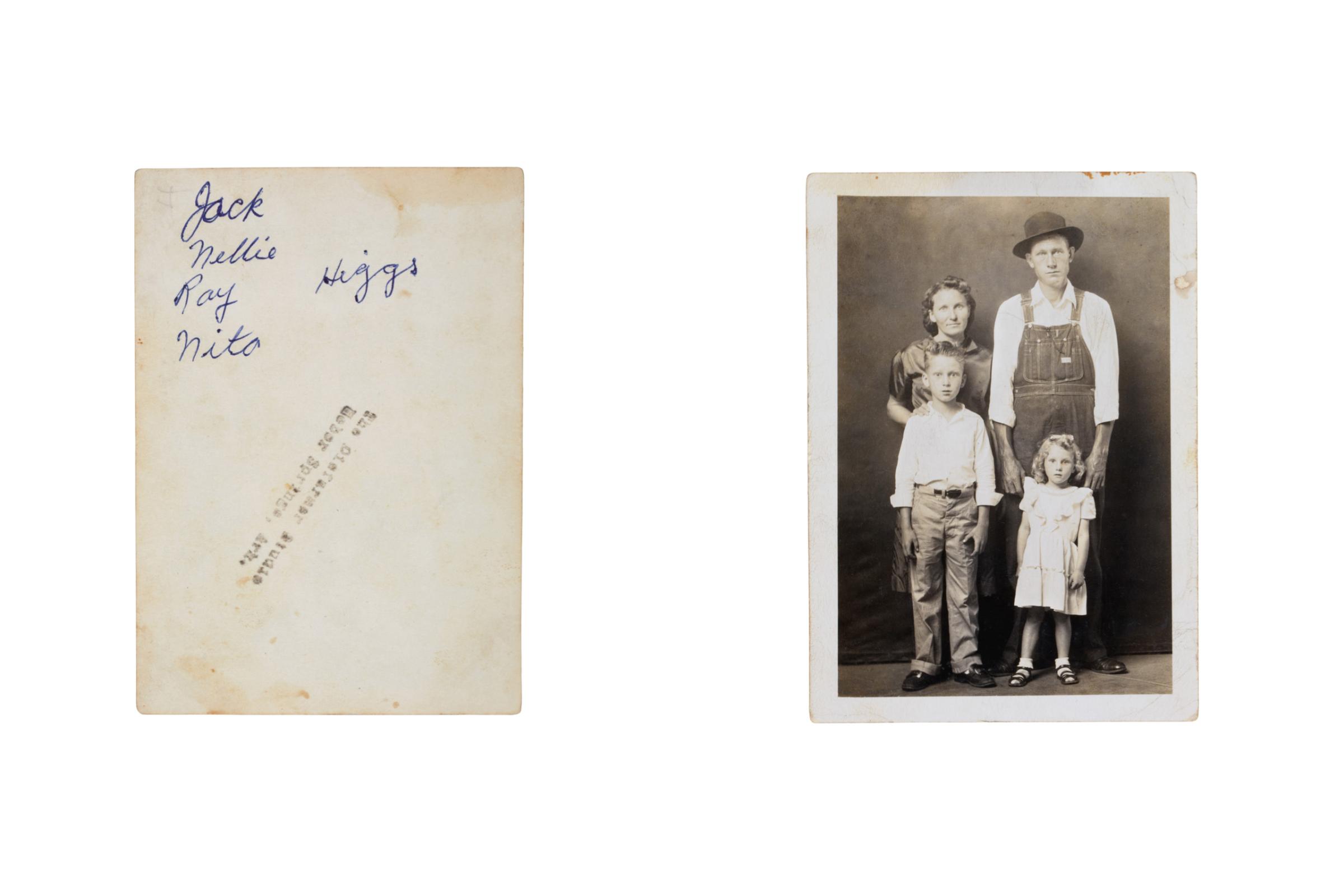

Twenty years later, Disfarmer’s impressive collection of portraits was rediscovered. The images, carefully restored and enlarged from his original glass plate negatives, sold for a fortune in the art market in the 1970s and secured him a spot in the history of American photography. In 2005, vintage prints made by the artist himself emerged, allowing people to reexamine his work through those authentic artifacts.

A narrative explaining his character as well as his style was also formed and reinforced over the years. Eccentric, crazy and deranged are words commonly associated with Disfarmer, and art critics claim to have found the evidence in his photographs: people in the portraits never smiled as they were told not to by the photographer.

The story of him changing his name from Meyers to Disfarmer in order to elevate himself from his distanced family also adds to the art world’s fascination with the genius artist. “The way that [an artist’s] biography gets used to explain the art, I find that to be problematic, especially with Disfarmer,” says Chelsea Spengemann, an art historian and curator of Becoming Disfarmer, a current exhibition at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, N.Y.

“People would make such simplistic links between the way people look at his photographs and his mental well-being,” she adds, “that to me just seems to be a very lazy interpretation in art history.”

As a result, the staff at Neuberger put together an exhibition that presents Disfarmer’s posthumously-made black-and-white photographs alongside his original prints, as well as newspaper clippings and historical journals. The arrangement, Spengemann explains, is meant to invite viewers to see Disfarmer’s work in a new light. “I wasn’t interested in trying to just repeat what has been done,” Spengemann says. “The exhibition brings up this vernacular history of Disfarmer’s work by juxtapositioning the vintage prints with the enlargements in the same room.”

Spengemann says the art world has tried hard to construct him as a self-taught genius that stood on his own, but in fact, his work is a part of the portraiture tradition. She also asks viewers to look at the images in the backdrop of the 70s when “interest in photography as an art form exploded.”

However, two collectors who offered their photographs to the exhibition didn’t receive Spengemann’s interpretation well. According to the curator, the collectors not only opposed her calling Disfarmer a vernacular photographer, but they also disliked her selection of the more damaged, less recognized photographs from their collection.

“I wanted to show the range of the work that existed by Disfarmer,” Spengemann says. “I didn’t want to just show the prettiest, most iconic work that has been reprinted over and over.”

The collectors responded with withdrawing their collections, one week after the first accompanying catalogue was printed. As a result, all 2,500 copies had to be destroyed and nearly half of the show needed to be replaced with new photographs.

But Spengemann says the event has only made her thesis stronger.

“The exhibition really tries to open up the history of Disfarmer’s portraits themselves, and also their posthumous history of what happened to his photos after his death,” Spengemann says. “The different ways they’ve appeared in the art world, and how that has affected their meanings; have given them this entirely new meaning.”

Being satisfied not knowing who Disfarmer really was, Spengemann believes the exhibition reveal “the avenues [his photographs] have gone down to become what they are today.”

Becoming Disfarmer is on view at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, N.Y. until March 22, 2015.

Phil Bicker, who edited this photo series, is a photo editor at TIME.

Ye Ming is a contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com