On July 27, 1953, a ceasefire ended open hostilities in the Korean War, and the United Nations, the People’s Republic of China, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) established a border and a demilitarized zone at the 38th parallel. After three years of fighting, the border between north and south was, in effect, exactly where it had been prior to the beginning of the war. The Republic of Korea (South Korea) refused to join the armistice; and, as a formal peace treaty was never signed, South and North Korea today remain technically at war, 60 years after the guns fell silent.

Nearly three million people died or went missing in the war, in which North Korean and Chinese troops fought an international force comprised largely of Americans. Of those three million, more than half were civilians, and most were Korean. Since the mid-1950s, meanwhile, the American military has maintained a heavy presence in South Korea; this footprint is the uneasy foundation that underlies relations between the two countries.

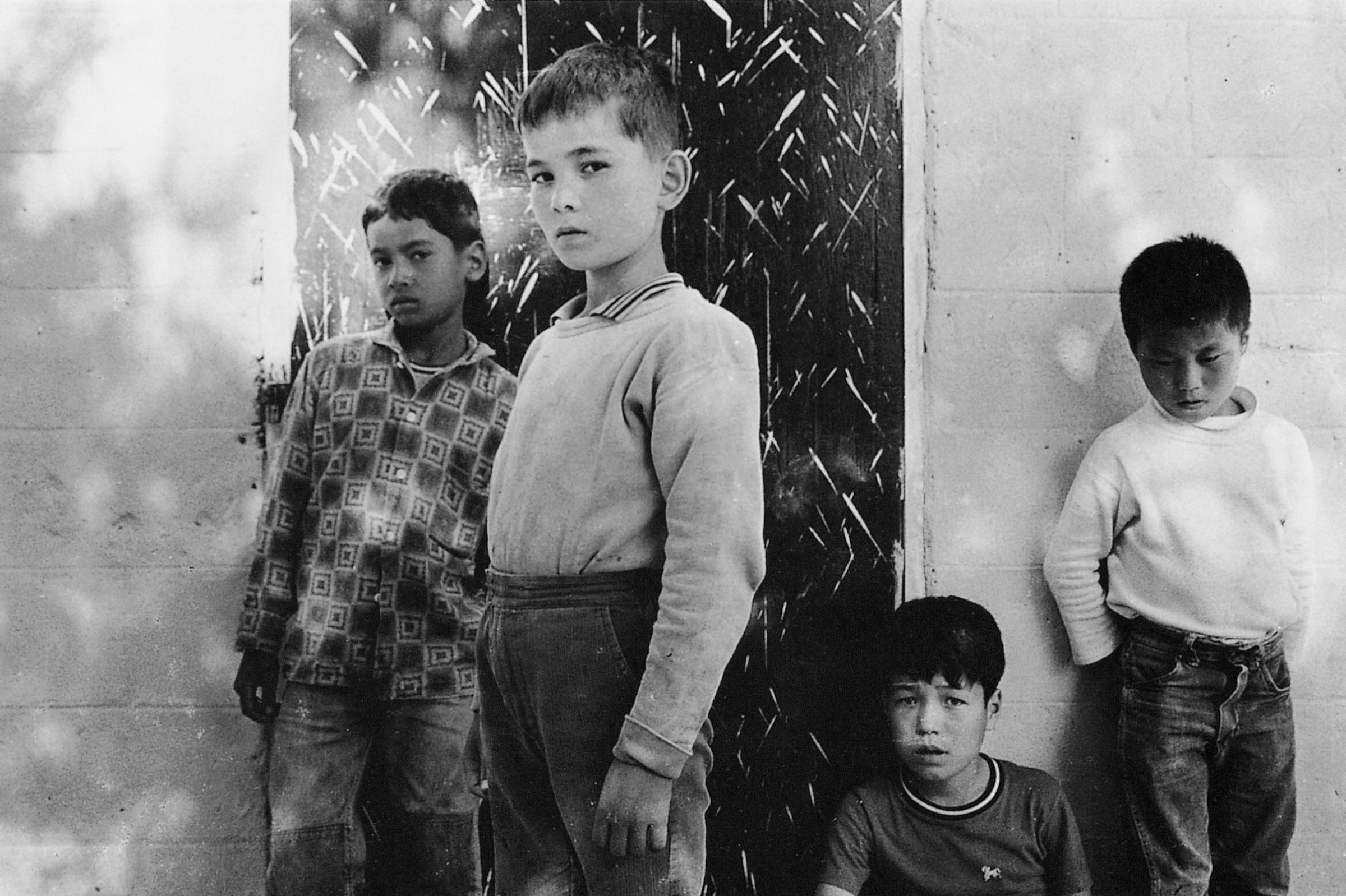

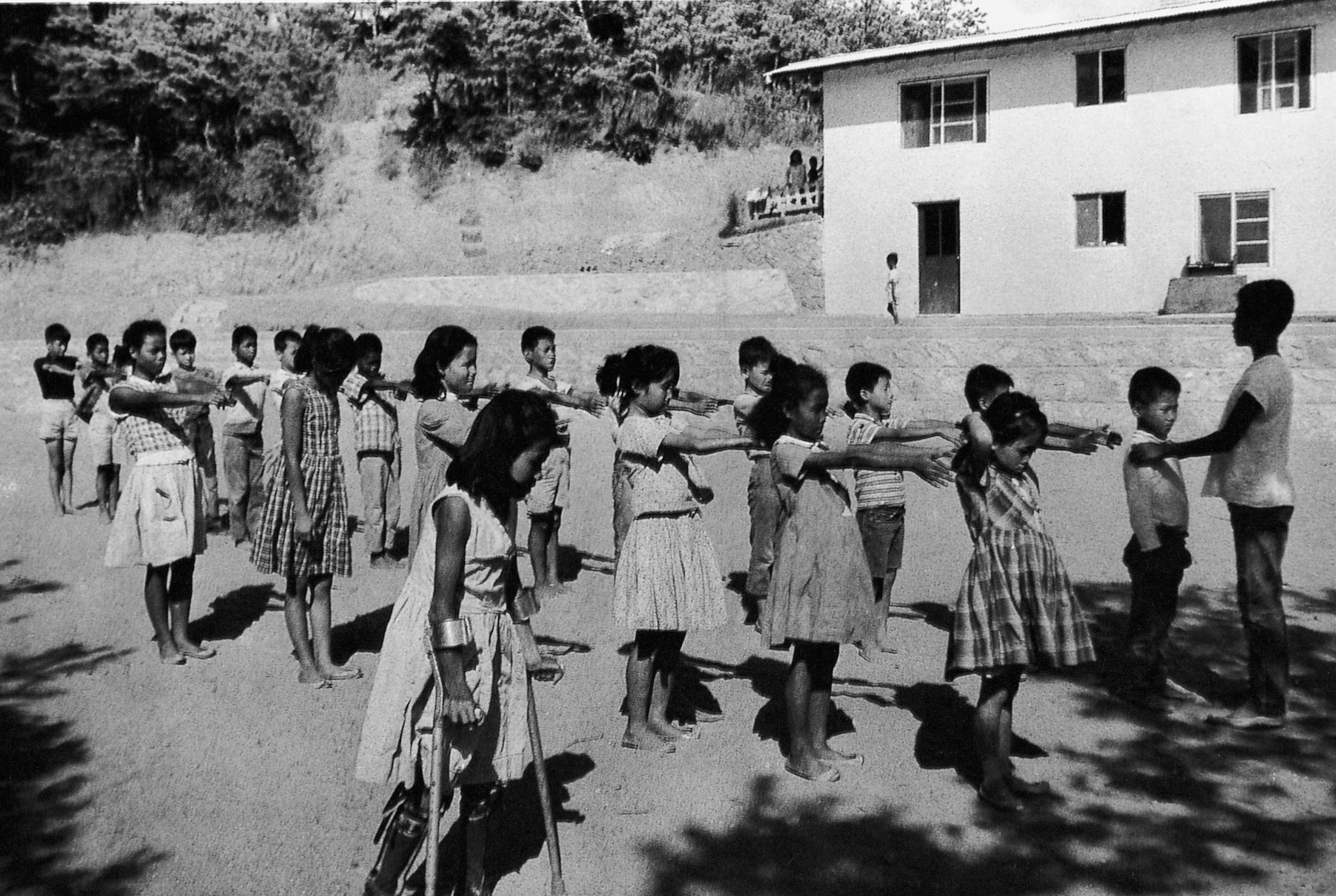

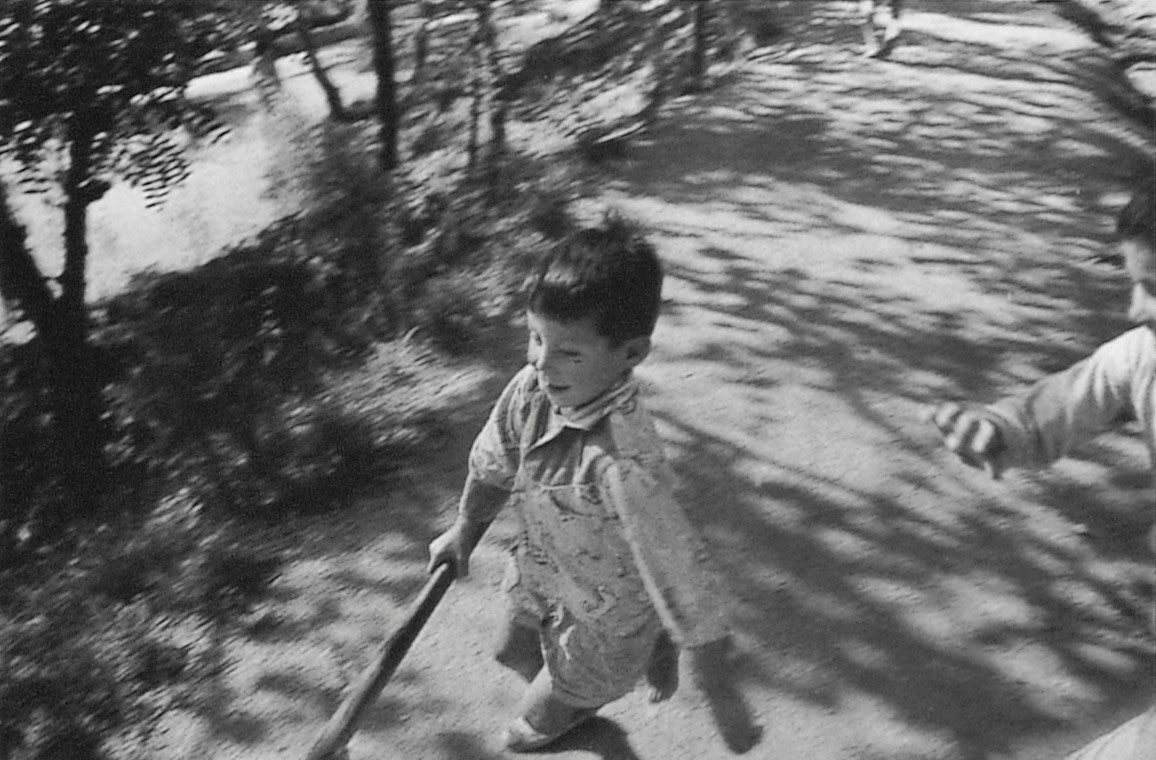

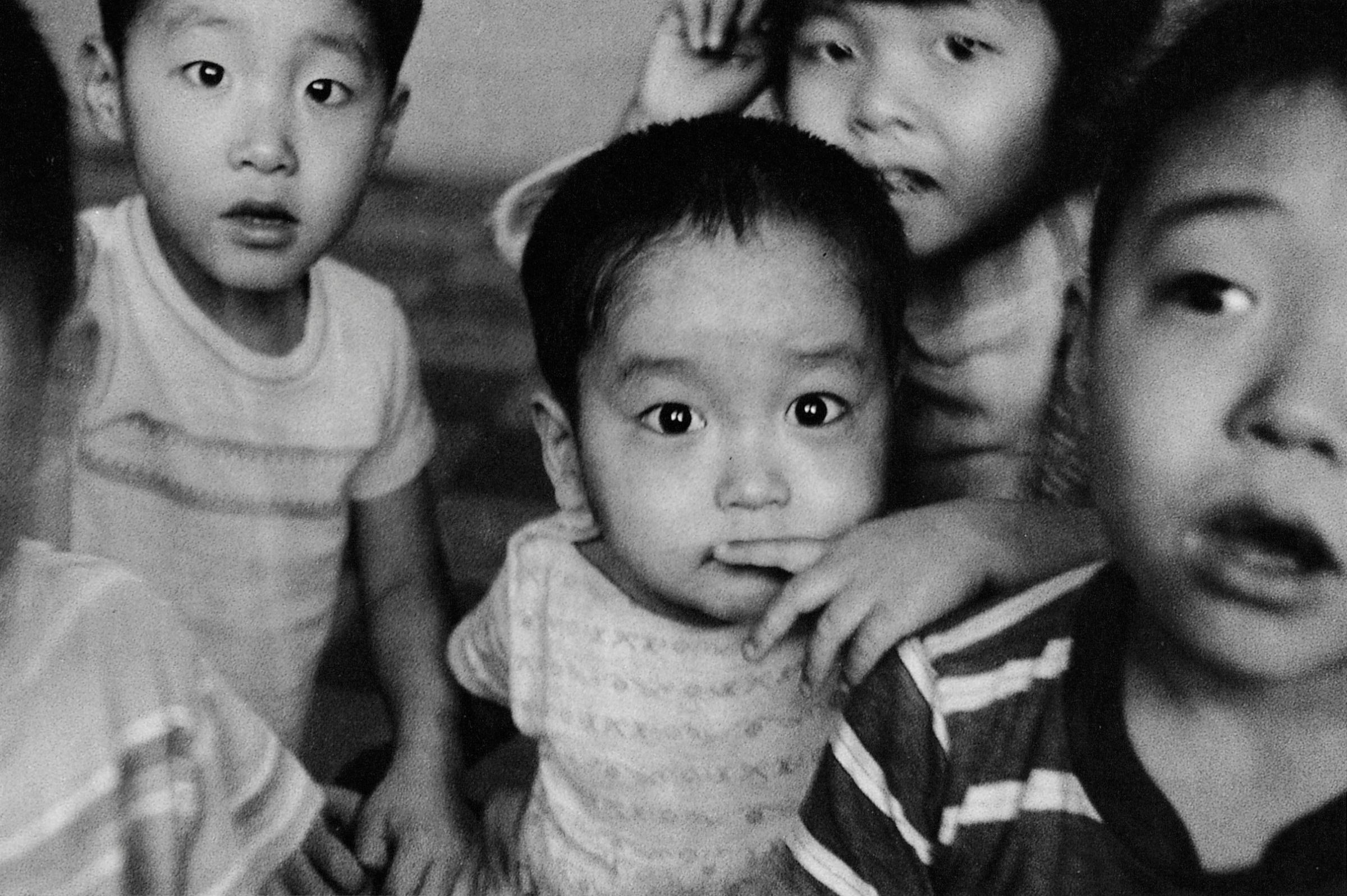

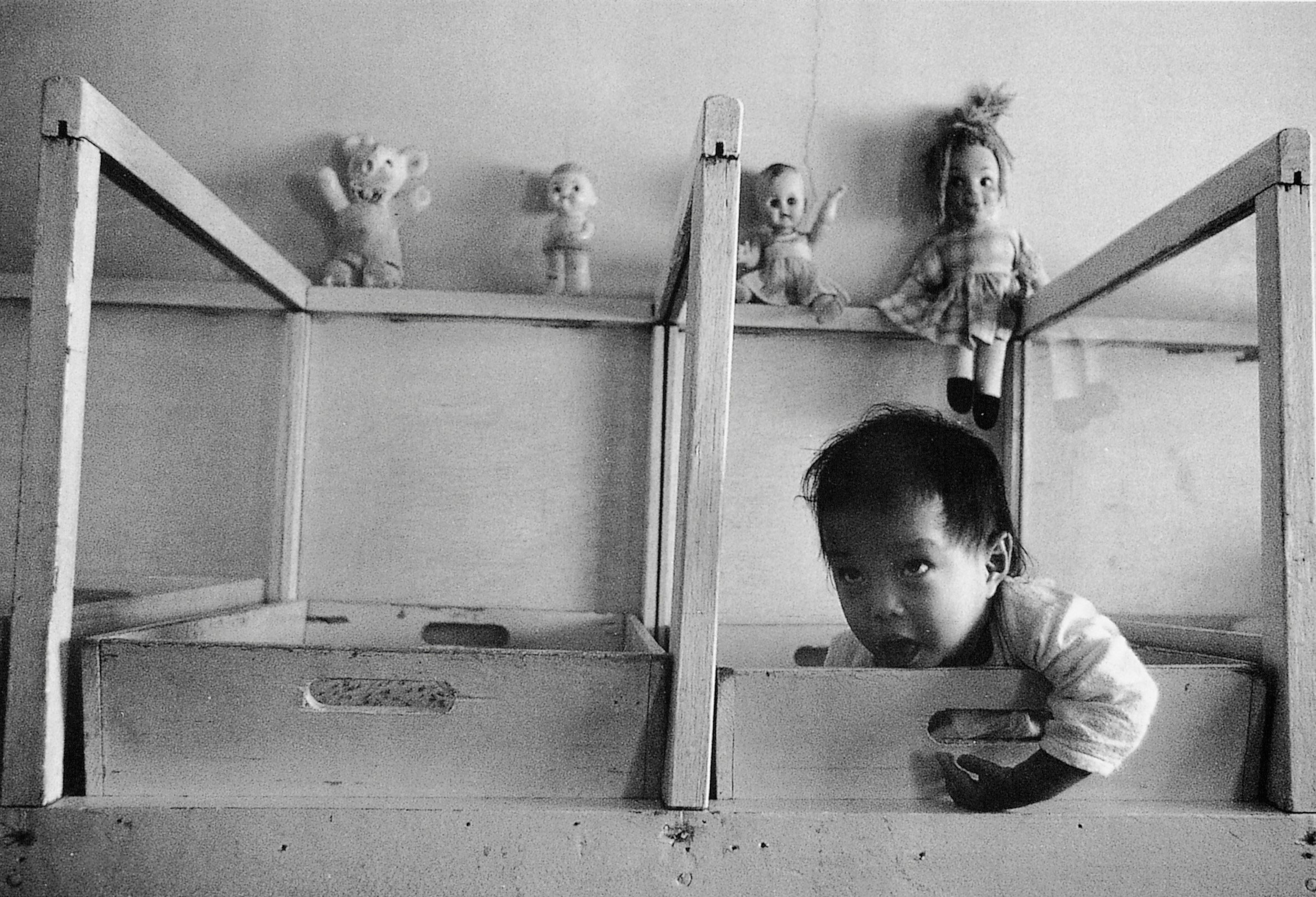

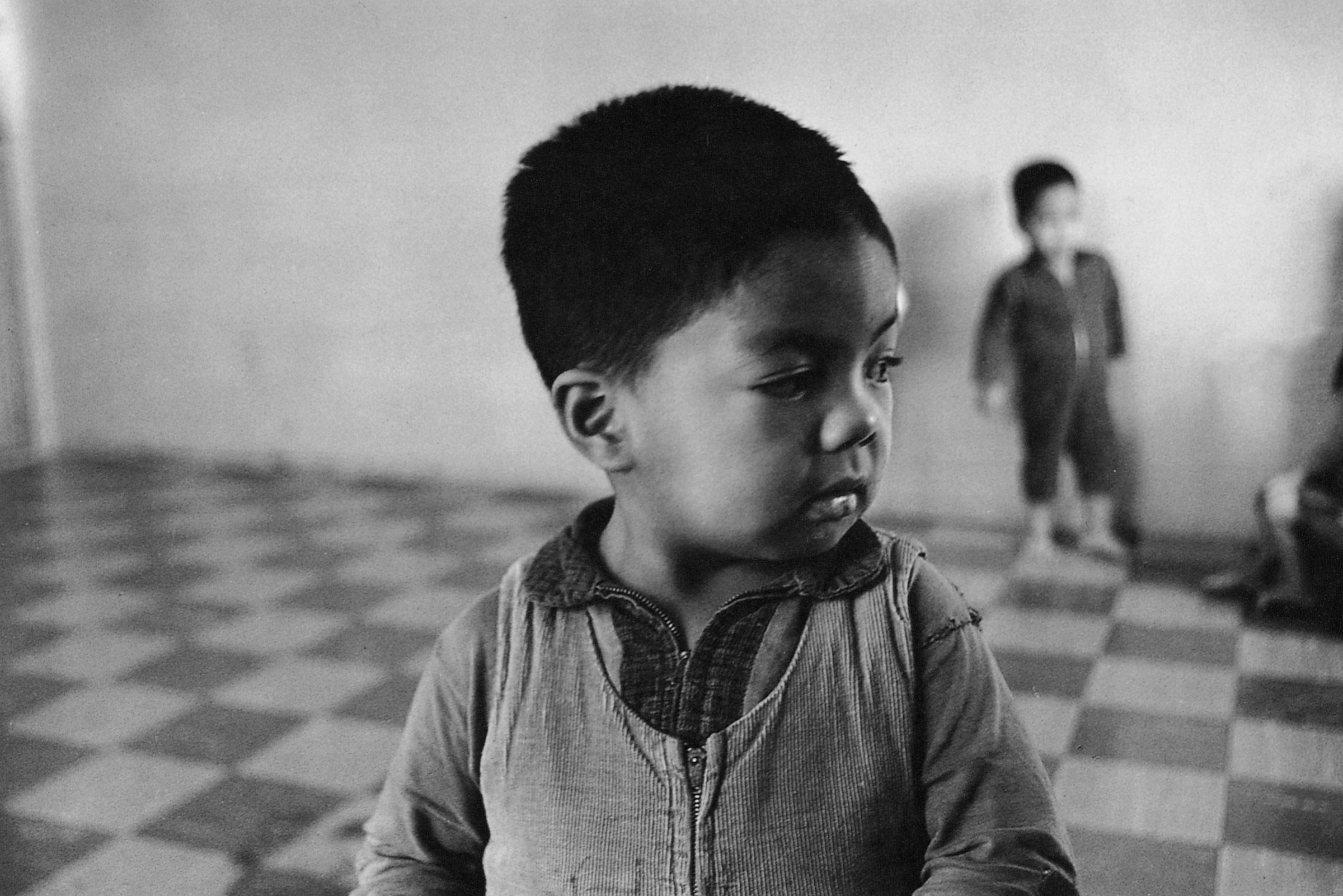

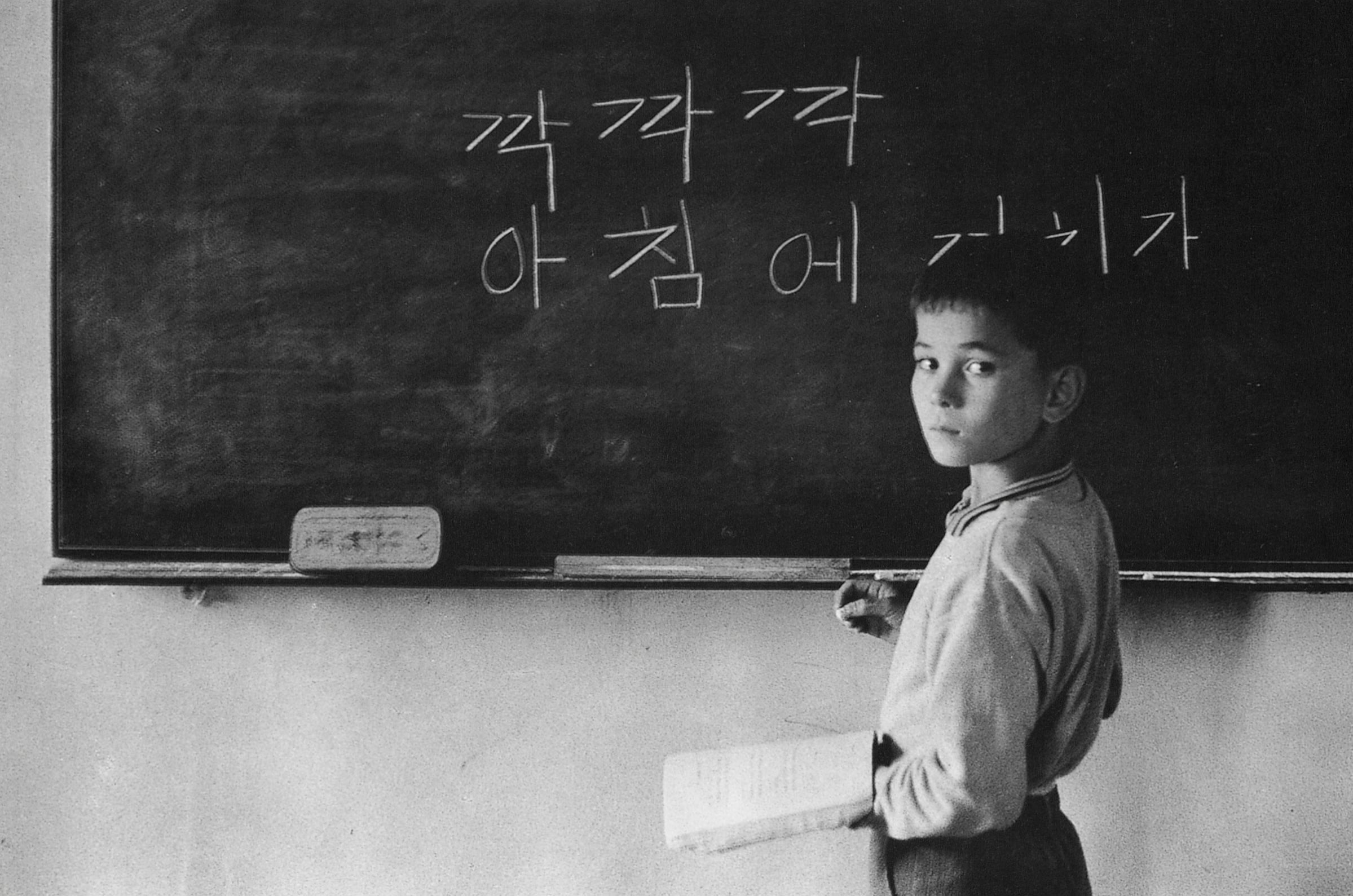

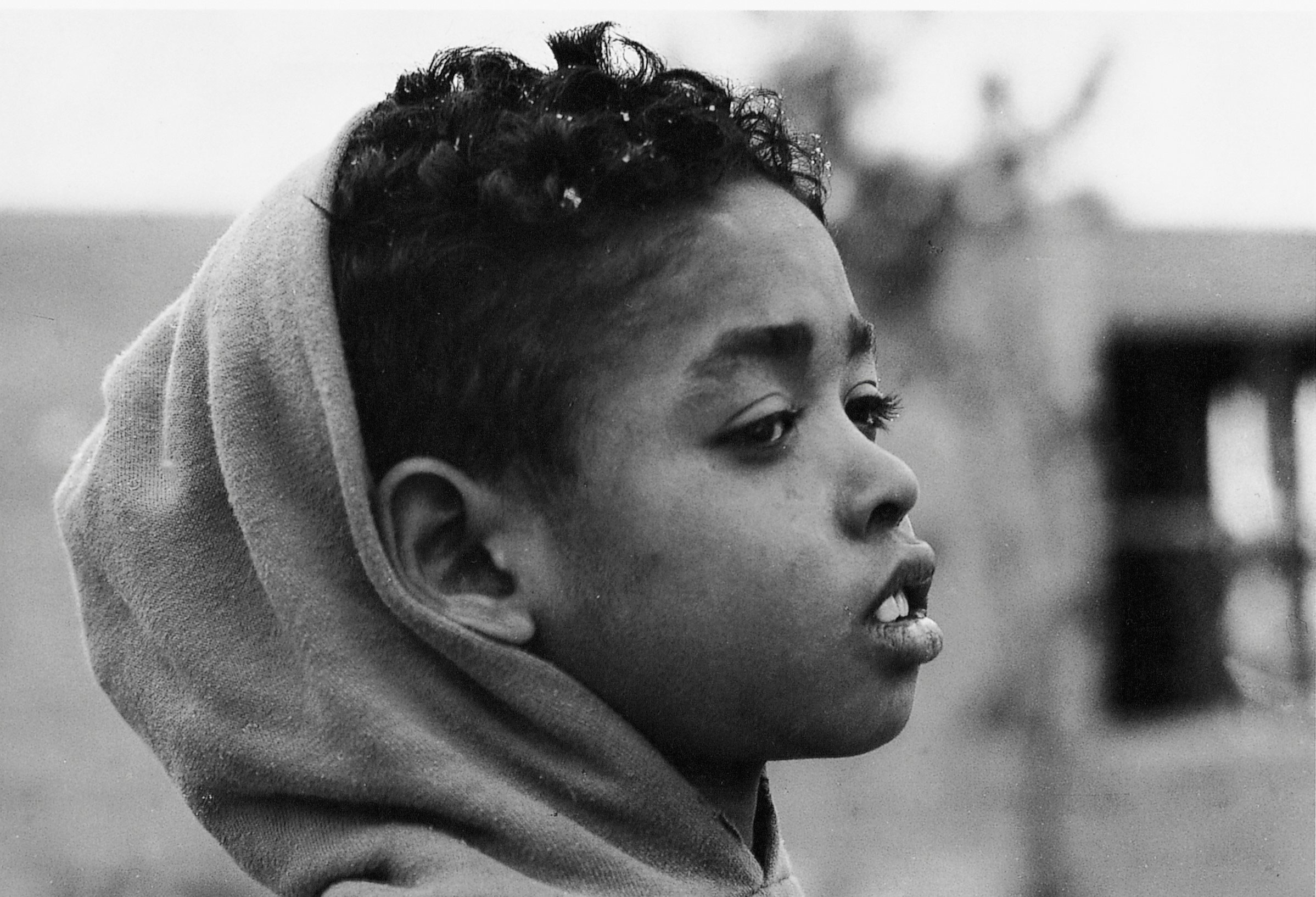

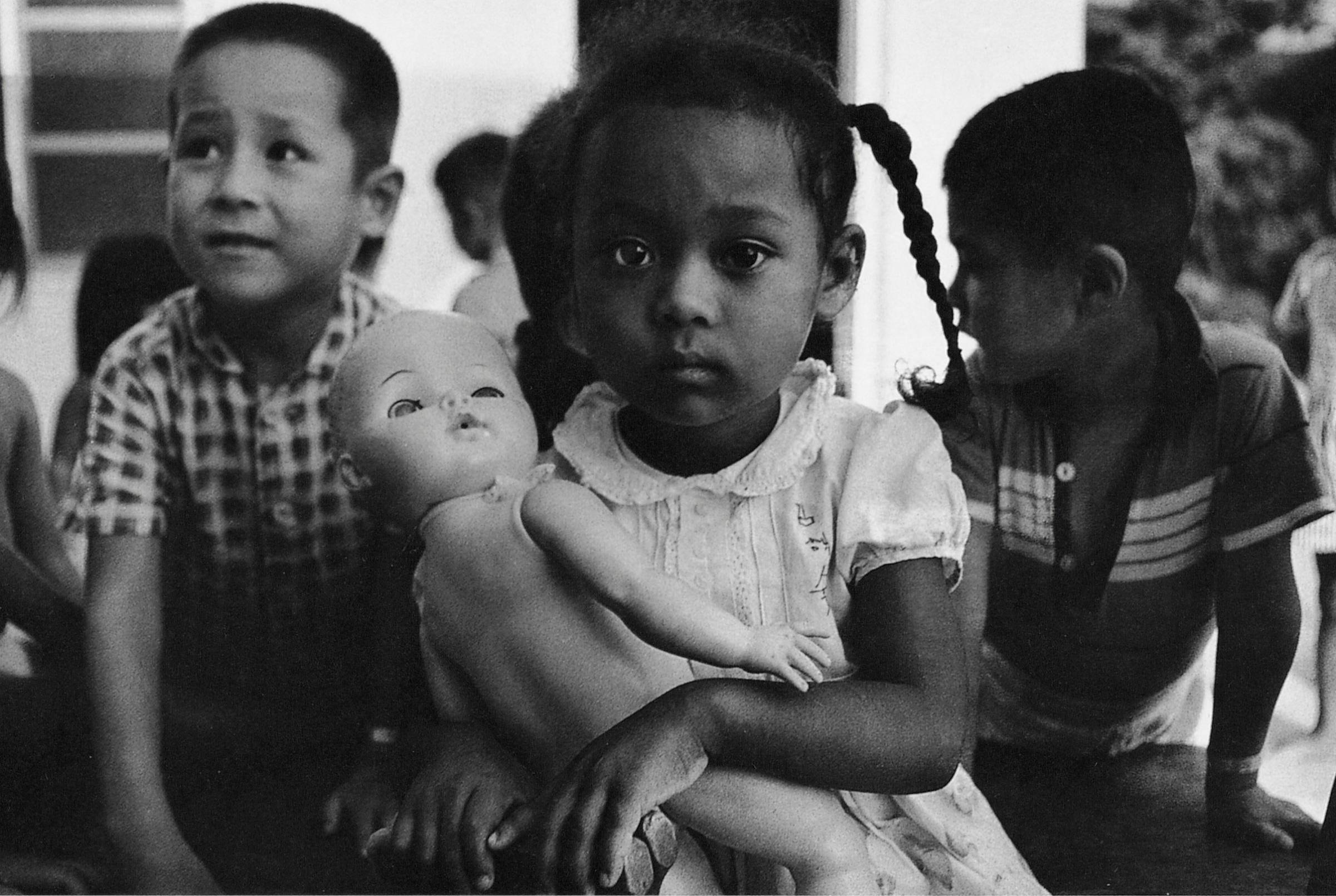

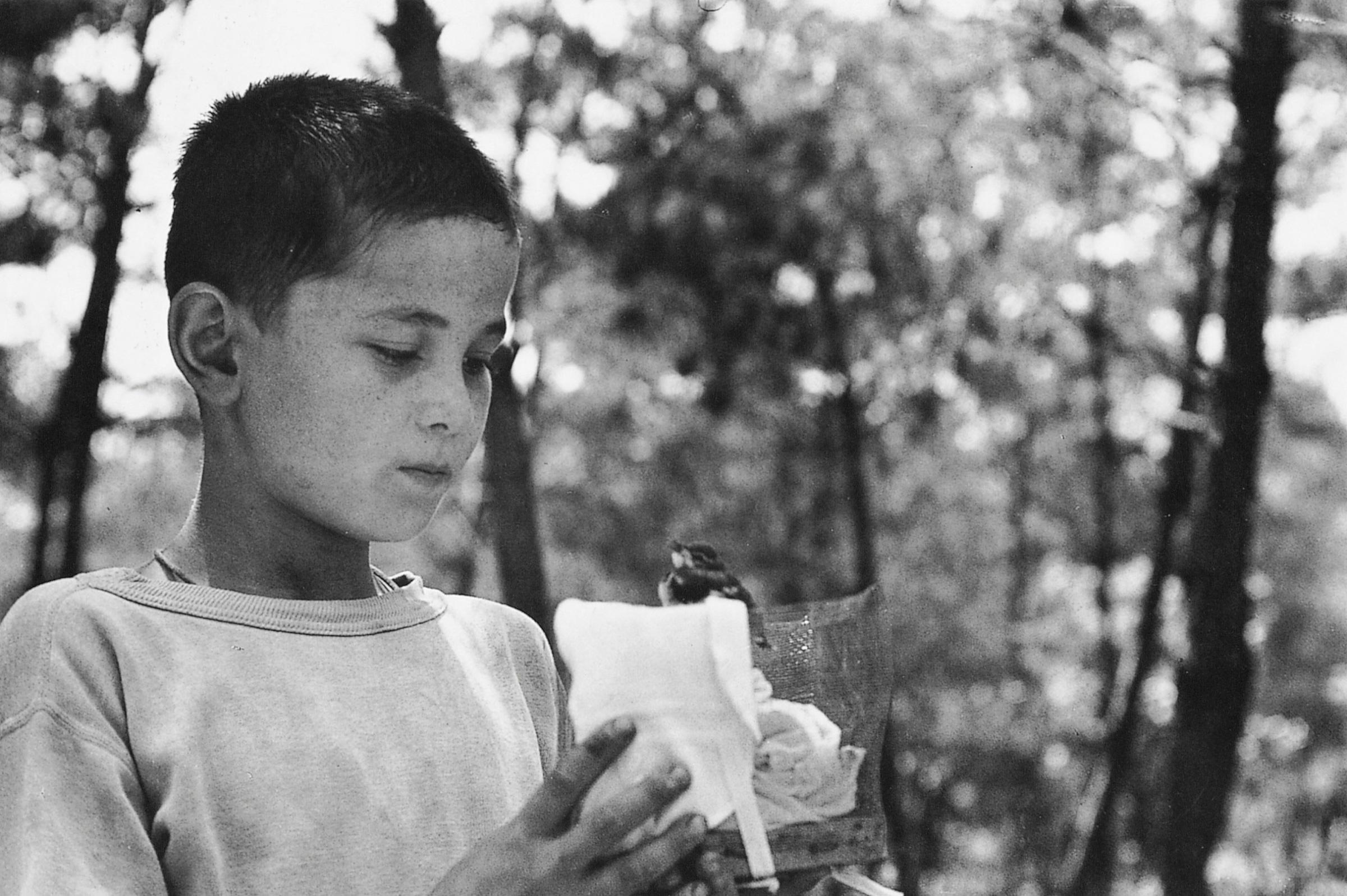

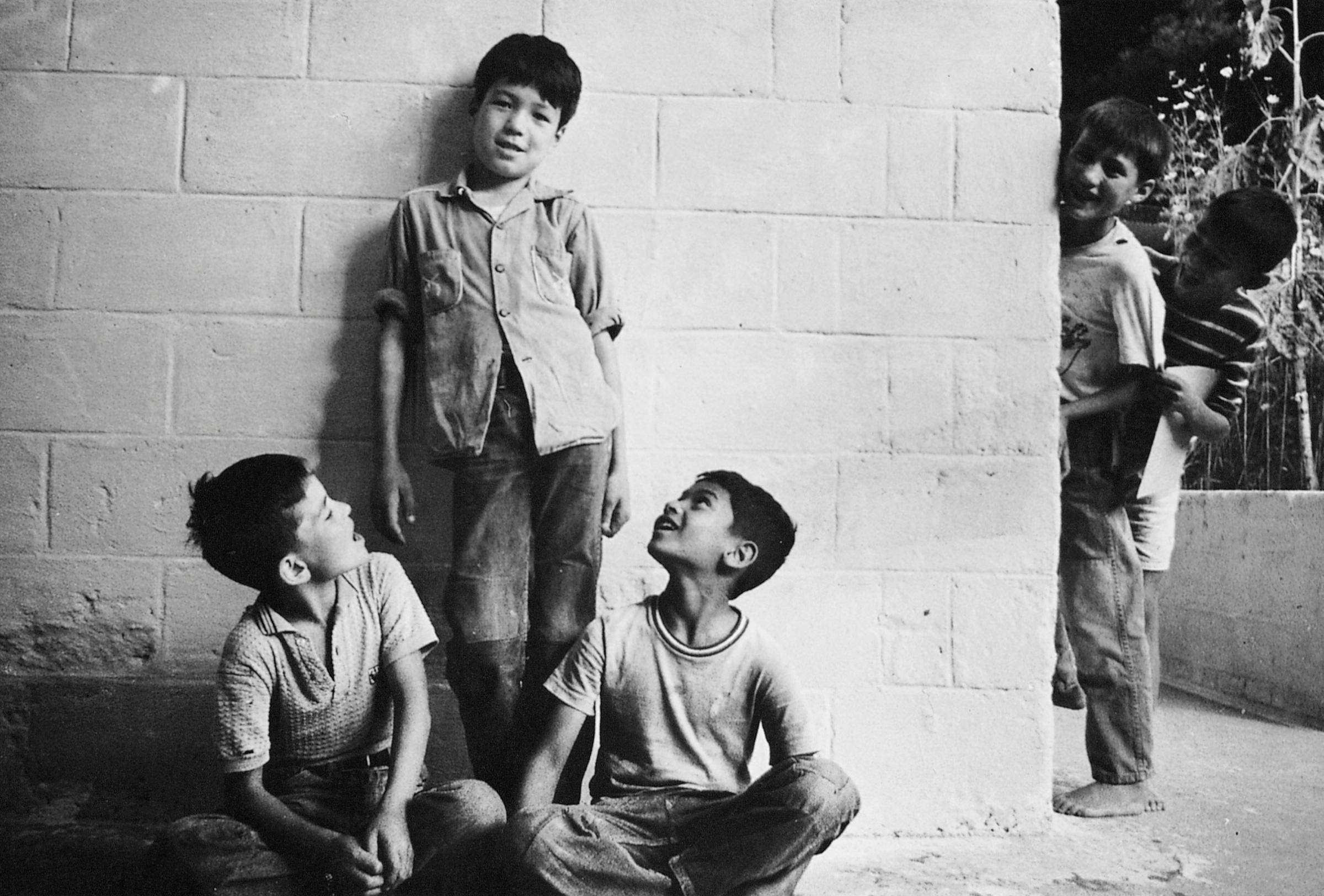

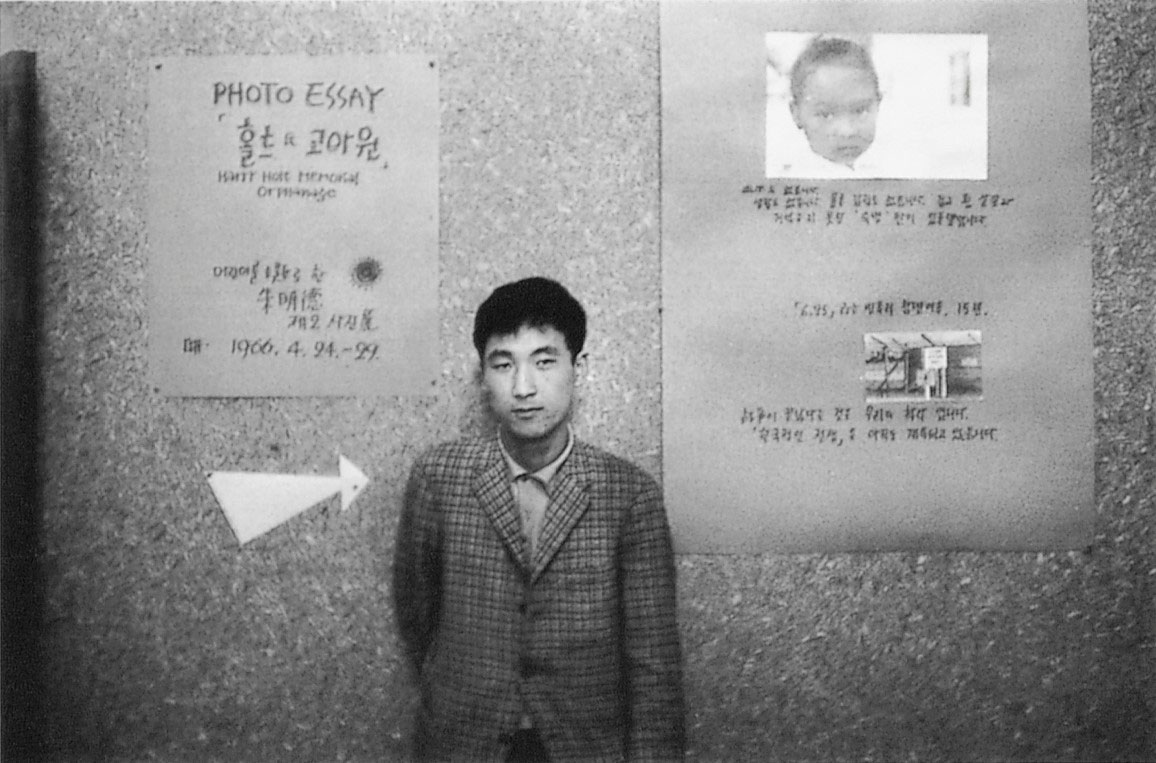

The photos in this gallery were made in the early 1960s by Joo Myung Duck, then a young photojournalist. They depict mixed-race orphans, the children of foreign servicemen and Korean women, at the Holt orphanage in Seoul. Most of these children were born after the war, and they were abandoned by nearly everyone: by their fathers, who rarely remained in Korea; by their mothers, who endured ostracism and social stigma; and by the Korean government, which endorsed a politics of racial purity and sought to expel mixed-race children from the country.

In exploring these realities, Joo’s photographs are at-once inquisitive, undaunted, and gentle, attending carefully to variations in racial appearance while suggesting the centrality of Christian faith at Holt. His highly formal compositions revel in visual detail. And, in large part, he avoids sentimentality.

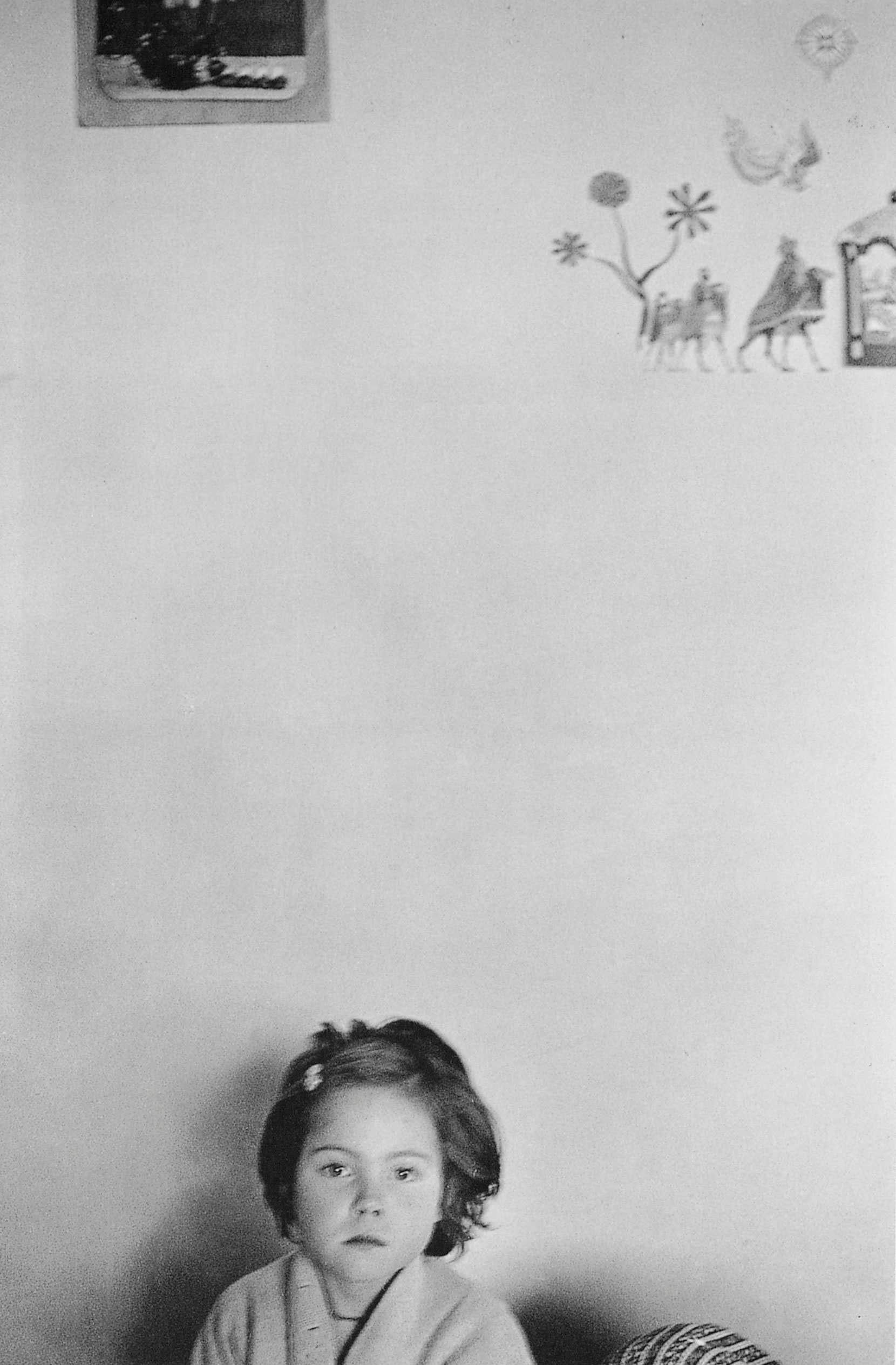

At their best, Joo’s images enact what sometimes feel like radical transformations. In one photograph (slide 8 in the gallery), a young girl faces the camera, her body outside the picture’s frame. Far above her head on the wall appears a stencil of shepherds approaching the manger in Bethlehem. In an instant, the wall assumes the air of a vast starlit desert; a viewer can empathize with the shepherds’ loneliness, doubt, and fear. An orphan might feel like that.

In another image (slide 11), seven children lie on a linoleum floor. Sleep has rendered their faces blank. Their bodies are arrayed in similar poses – stomach down, head turned to the side – and that very uniformity imparts a particular stillness. One searches for identifying traits: a scar, a cowlick, freckles. With the slightest change of perception, one might be gazing at bodies in a grave.

Despite everything, traces of beauty persist here. In the fourth picture, two children race around the photographer, as Joo whirls to follow them with his camera. The boy being chased appears to smile, perhaps even to laugh. Behind him, shadows of tree branches paint the ground. The sun was shining that day.

David Kim is a student at Yale Law School, where he curates an art and human rights initiative. He also collaborates with Council, a Paris-based arts organization. Contact him here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com