“Plymouth Rock is a glacial erratic at rest in exotic terrane.” So begins John McPhee’s classic 1990 New Yorker article, the best short piece ever written about the great American relic, pointing out how geological forces carried this rock far from its original home — Africa. It is an iconic mass of granite geologically formed by fire, but it certainly also qualifies as a sedimentary and metamorphic chunk of American political culture. Plymouth Rock has long been a symbol of America’s beginnings, the country’s bedrock, its very foundation. And in the Rock’s surprising travels, during its original journey to Plymouth Harbor and its subsequent wanderings and memorialization, it has embodied authentic Americanism, on the move.

As a historian of early America, I’ve long been fascinated by how the people, places, and things of the colonial era have been remembered in American popular culture — that is, in the sort of history that “we carry around in our heads,” not the history that history professors profess. And the Pilgrims and Plymouth Rock do feature prominently in our collective heads, particularly as November arrives each year and we turn our attention to Thanksgiving. Why make such a big deal of a small band of Puritan separatists who were not the first European colonists of America, and not even the most prominent Puritan colonists of Massachusetts? And did they actually ever step on Plymouth Rock, or treat it as anything other than an erratic? All this seems not to matter; I long ago resolved that history is and should be much more than mere debunking.

In the early 1990s, while on a ferry in New York Harbor, I overheard a conversation that demonstrated the ongoing significance of those Plymouth “forefathers.” Anticipating their visit to the historic Ellis Island and eyeing the Statue of Liberty in the distance, one passenger said to another, “These immigrants were just doing what the very first Americans, the Pilgrims, were doing.” Her companion nodded toward the island and agreed: “That was their Plymouth Rock.” Fractured history, yet rock-solid nonetheless.

McPhee reconstructed the Rock’s migration, via the mechanisms of plate tectonics, as part of a large slice of the earth’s crust called Atlantica, which joined North America some 580 million years ago from a distant locale — Africa, mostly likely. Then, approximately 20,000 years ago, the boulder was scooped up by moving ice and ultimately deposited at Plymouth Harbor when glaciers retreated at the end of the Ice Age. After the Pilgrims showed up in 1620, the Rock’s migrations only accelerated, as people circulated its shards as relics, just as believers disseminated the bones of saints and pieces of the true cross in medieval Europe to help sanctify a holy narrative. In this case, they were shoring up a New World narrative about the glorious rise of the American republic.

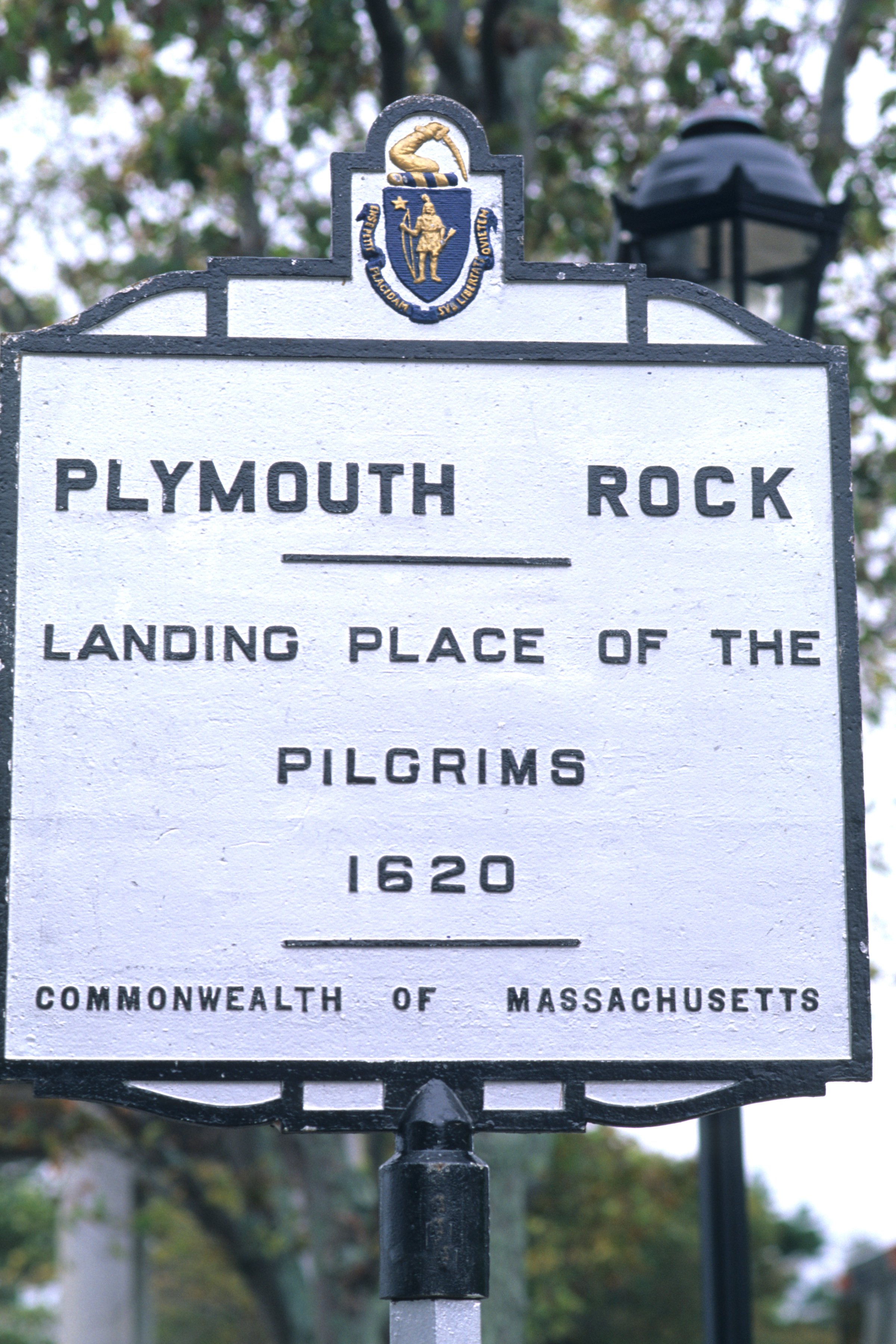

Until late in the 18th century, the Puritan Separatists who founded Plymouth colony in 1620 were but one marginal group of predecessors, not yet Capital-P “Pilgrims,” not yet the nation’s forefathers. Plymouth Rock belatedly received its first public recognition as the Pilgrims’ alleged landing place when church elder Thomas Faunce assembled his children and grandchildren on the spot and recited the tale in 1742, a legend later fossilized in print by Dr. James Thacher, who provided no corroborating evidence. The Separatists’ narrative and their Rock acquired symbolic power during the American Revolution, as the new United States sought independence.

By the late 1700s, Thanksgiving had become a well-established regional festival in New England, tracing its roots to a feast in the autumn of 1621. Plymouth Rock, however, was at first more directly tied to a different occasion: Forefathers’ Day, or Landing Day, on December 22, commemorating the debarkation of the Mayflower passengers in 1620. Popular among fraternal ancestor organizations, Landing Day was a civic event that expressed exclusivity, expansionism, and stubborn mission, while Thanksgiving was a domestic and community fete celebrating bounty, charity, and inclusion, And while both holidays spread beyond New England, carried by migrating Yankees who shared the Rock as a touchstone, only Thanksgiving’s spirit overtook the hearts and festive calendars of Americans.

Toasting the Pilgrims at a New England Society fete near the end of the 19th century, Frederic Taylor of New York proclaimed:

It is our habit to think of Plymouth Rock always as being at Plymouth, and nowhere else. Well it was there once [but] when the Pilgrims’ feet pressed that boulder at Plymouth it became instinct with life and began to broaden at its base; and its base has ever since been spreading out, till now Plymouth Rock underlies the continent.

Using the Rock as potent metaphor, Taylor imagined it as a stepping-stone and foundation for Union generals Grant and Sherman, as ballast for the Monitor as it defeated the Merrimac, and as Abraham Lincoln’s hammer of freedom.

Given the seismic tumult of American history, it’s perhaps no surprise that the gravitas surrounding the Pilgrims would be shaken. The 19th-century New York lawyer and politico Chauncey Depew, a frequent after-dinner speaker at New England Society banquets, once tweaked his patrician audience with this cheeky comment: “What a pity instead of the Pilgrim Fathers landing on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock had not landed on the Pilgrim Fathers,” which set off a chain of similar jokes over the years, including in the opening lines of the Cole Porter standard “Anything Goes.”

Few relished deflating the puffery of Pilgrim celebrations as much as Mark Twain. He once facetiously urged attendees at a New England Society dinner to sell their chief asset: “Opulent New England [is] overflowing with rocks,” and “this one isn’t worth at the outside, more than 35 cents.” As Twain knew, this was no ordinary rock, not even merely a brand name, but a priceless relic, providing a more visceral link to the past, what one scholar has called a “zero-hand” account. Relics — including Plymouth Rock —are “things that speak.”

But the Rock could sometimes speak in controversial and unpredictable ways. In the bicentenary celebration at Plymouth in 1820, for example, the orator Daniel Webster linked it (somewhat creatively) not only to religious freedom but also to the anti-slavery cause. (Many Southerners initially resisted the celebration of Thanksgiving itself because it seemed to carry the taint of abolitionism.) One fragment later helped raise money for the Union effort in the Civil War at a Boston Sanitary Fair in 1863.

Disturbingly for some descendants of “First Comers,” the Rock could sometimes be claimed by other latter-day “pilgrims” — from Ireland or Italy, Poland or Puerto Rico. Its message has been pluralism as well as nationalism and chauvinism. And if the Rock powerfully symbolizes the United States as a nation of immigrants, ironically this granite boulder from Africa might better represent those immigrants who came against their will, in chains, in the largest forced migration in history. For non-immigrants — Native Americans — it sometimes served as a potent prop in their struggle for recognition and rights.

Sometimes relics fall mute. In the 1920s, the Plymouth Antiquarian Society (and later the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History) acquired a large piece that had been cut from the doorstep of a house in Plymouth. A fragment of another rock at the Smithsonian — a craggy nugget chipped from the Mother Rock by Lewis Bradford in 1830, inscribed with the precise details of its collection and transformation into a circulating talisman — sat silently for years among a collection that had been donated in 1911. It only regained a “speaking part” in the museum’s displays and publications in the late 20th century.

Plymouth Rock is an emblem defined by its solidity. And yet it’s been anything but solid, in form or meaning. It’s been split, carted about, fragmented, broken and rejoined, reinstalled at the Plymouth waterfront, canopied, repaired. It has endured the changing forces of nature and American political culture. Its precious pieces have spread far and wide, across the Atlantic and to the shores of the Pacific, and they’ve been further disseminated through print and pixels, extending the Mother Rock’s power and reach. It’s clear that Plymouth Rock and its mobile relics still speak to us, in a voice that is both constant and changing.

Matthew Dennis is professor of history and environmental studies at the University of Oregon. He is the author or editor of five books, including Red, White, and Blue Letter Days: An American Calendar, and is currently at work on American Relics and the Politics of Public Memory. He wrote this article for Zocalo Public Square.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com