This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Carl didn’t know what was happening to his wife. The German railway clerk from Morfelder Landstasse and his wife Auguste had been happily married for twenty-eight years. They had one daughter, Thekla, and their marriage had always been harmonious; that is, until one Spring day in 1901 when Auguste suddenly exhibited signs of jealousy.

Auguste accused Carl of going for a walk with a female neighbor, and since then, she had been increasingly mistrustful. Carl thought that this sudden jealousy was unfounded. Over the next several months, Auguste’s memory began to fade. The once orderly and industrious homemaker was making uncharacteristic mistakes in preparing home meals — a task that she had probably performed countless times. She wandered aimlessly around the apartment, leaving housework unfinished. She became convinced that a cart driver who frequented their house was trying to harm her and that people were talking about her. Without explanation, she began to hide various objects around the house. The couple’s neighbors sometimes discovered Auguste ringing their doorbells for no reason.

Prior to this change, Auguste had never been seriously ill. She was an otherwise healthy 51-year old woman who did not drink alcohol nor suffered from any mental illness. By November of 1901, Carl was at wit’s end. He had no choice but to take his wife to the local mental asylum. The physician’s admittance note described her as suffering from a weak memory, persecution mania, sleeplessness, and restlessness that rendered her unable to perform physical or mental work.

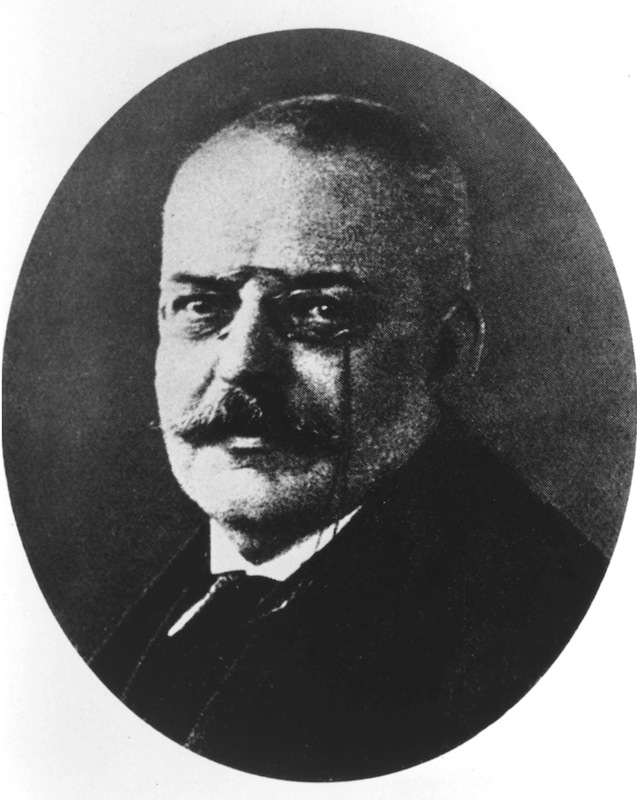

The following day, the senior physician at the Asylum for the Insane and Epileptic in Frankfurt am Main came across Auguste’s clinical notes. The unusual case seemed to stick out and the psychiatrist sensed that there was something special about Auguste. It was the case that he was waiting for. Dr. Alois Alzheimer decided that he should see Auguste for himself.

Over the next several months, Dr. Alzheimer interviewed and examined Auguste, whose condition continued to deteriorate. He asked her to name common objects, perform simple arithmetic, tell him where she lived, what year it was, the color of snow, the sky, grass, and so on. Alzheimer maintained a detailed record and even arranged for Auguste to be photographed. One photo reveals a woman with a deeply furrowed forehead and heavy bags under her eyes. She was wearing a white hospital gown and her face had a tired, blank expression, with perhaps a hint of fear. Her hands were draped over her raised knees, with the long fingers securely interlocked.

What struck Dr. Alzheimer was Auguste’s relatively young age. He had seen cases of mental deterioration in much older patients and had theorized that age-related thickening of the brain’s blood vessels led to brain atrophy. It was unusual, however, to see the condition in a person who was only fifty-one years old. Dr. Alzheimer had only encountered one other case similar to Auguste’s. The autopsy findings on that patient revealed shrinkage in specific brain cells but no significant blood vessel thickening.

Dr. Alzheimer continued his daily visits and long conversations with Auguste. There was no cure, of course, and the limited treatments included the use of sedatives and warm baths. At times, Auguste had to be placed in isolation after she groped faces and struck other patients in the clinic. She wandered aimlessly, sometimes screamed for hours, and became increasingly hostile. By February of 1902, her condition had advanced to the point that long conversations and physical examinations became impossible.

On April 8, 1906, after nearly five years of progressive mental and physical decline, Auguste died. The official cause of death was blood poisoning due to bedsores. Dr. Alzheimer suspected that behind her mental illness was a strange disease, and that perhaps examining her brain would offer some clues. When he examined the brain sections under the microscope, his suspicion was confirmed. Dr. Alzheimer described changes in the neurofibrils — the protein filaments found in brain cells. He also saw peculiar deposits that he referred to a “millet seed-sized lesions.” These pathologic findings — now known as neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits – characterize the brains of Alzheimer’s Disease patients.

Dr. Alzheimer’s discovery was not immediately well received. In fact, the first time he presented Auguste’s case and autopsy findings during a German Psychiatry conference in 1906, the reception from the audience was rather cold. This was the time when psychoanalysis and the Freudian views on the relationship between childhood trauma and mental illness were, in today’s parlance, the “trending” topics in psychiatry. Correlating mental or neurologic disorders with histopathologic findings was not yet firmly established nor accepted. Ninety years later, in 1998, researchers re-examined Auguste’s original brain sections and confirmed the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques.

Emil Kraepelin, one of the most prominent psychiatrists in the early 1900s, first mentioned the term ‘Alzheimer’s Disease’ in the 1910 edition of his textbook on psychiatry. The disease was of course still poorly understood, but one of the most famous medical eponyms was born.

Today, there are an estimated five million Americans diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. The number is expected to rise as the population ages. There is no cure, and the burden on the afflicted as well as caregivers remains tremendous. The economic burden is also substantial, with healthcare costs for dementia in general estimated to be over $200 billion dollars in 2010. Researchers are on a quest to find effective treatment in areas that include stem cell and gene therapy.

Rod Tanchanco is a physician specializing in Internal Medicine. He writes about events and people in the history of medicine. His personal blog is at talesinmedicine.com.

References

Maurer K. Alzheimer : the life of a physician and the career of a disease. New York: Columbia University Press; 2003.

Graeber MB, Kösel S, Grasbon-Frodl E, Möller HJ, Mehraein P. Histopathology and APOE genotype of the first Alzheimer disease patient, Auguste D. Neurogenetics. 1998;1(3):223–8

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com