Dec. 1 has been World AIDS Day since 1988 — but though the awareness and activism around the diseases has changed drastically during the years between then and now.

To see just how much our understanding and attitudes have evolved, take a look back at TIME’s coverage of AIDS through these seven essential stories:

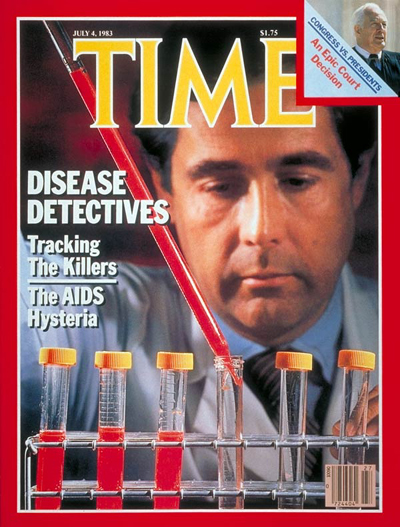

Hunting for the Hidden Killers by Walter Isaacson, Jul. 4, 1983

This 1983 cover story wasn’t the first time AIDS appeared in the pages of TIME — in 1982, an article had explained the new “plague” to readers — but the tale of the “disease detectives” at the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institutes of Health highlights just how little was known about the disease:

Based on what is known so far, two theories have emerged. One is that AIDS is caused by a specific agent, most probably a virus. “The infectious-agent hypothesis is much stronger than it was months ago,” says Curran, reflecting the prevailing opinion at CDC. NIH Researcher Fauci, who staunchly believes that the culprit is a virus, has been collecting helper T-cells from AIDS victims to look for bits of viruses within their genetic codes. So far, however, this and other complex methods of detecting viruses have yielded nothing conclusive. Suspicion focuses on two viruses: one is a member of the herpes family called CMV; the other, called human T-cell leukemia virus, or HTLV, is linked to leukemia and lymphoma.

The other theory is that the immune system of AIDS victims is simply overpowered by the assault of a variety of infections. Both drug users and active homosexuals are continually bombarded by a gallery of illnesses. Repeated exposure to the herpes virus, or to sperm entering the blood after anal intercourse, can lead to elevated levels of suppressor Tcells. The immune system eventually is so badly altered that, as one researcher puts it, “the whole thing explodes.” Other experts combine the two theories, speculating that a new virus may indeed be involved, but that it only takes hold when a combination of factors affects the potential victim, such as an imbalanced immune system or certain genetic characteristics.

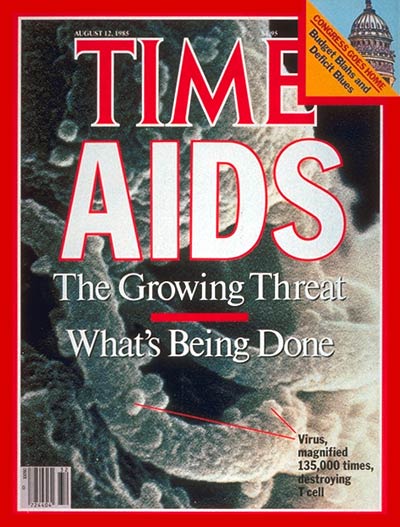

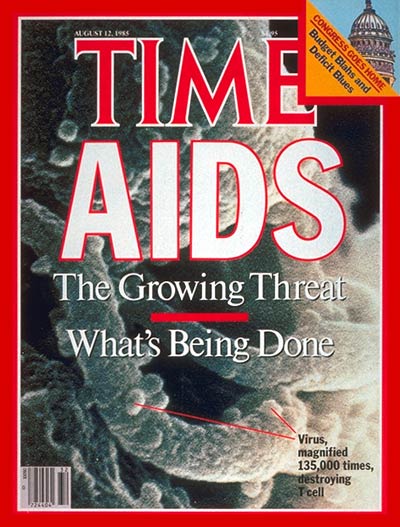

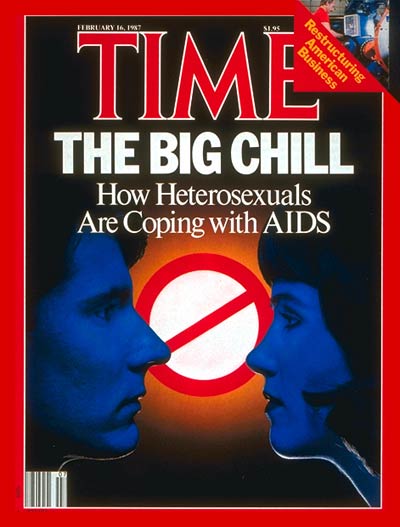

AIDS: A Growing Threat by Claudia Wallis, Aug. 12, 1985

As AIDS spread, so did awareness and knowledge — as well as paranoia:

Despite their physical ordeal, many AIDS sufferers say that the worst aspect of their condition is the sense of isolation and personal rejection. “It’s like wearing the scarlet letter,” says a 35-year-old Harvard-educated lawyer who was forced out of a job at a top Texas law firm. “When people do find out,” he says, “there is a shading, a variation in how they treat me. There is less familiarity. A lot less.” Sometimes the changes are far from subtle, according to Mark Senak, a lawyer at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, a volunteer organization that helps AIDS patients in New York. “They’ll come out of the hospital, and their roommate has thrown them out–I mean literally,” he says. “Their clothes will be on the street.” Rejection of this sort is not unique to gay men. Senak cites the case of a heterosexual woman with AIDS whose husband and family refused to take her back home from the hospital.

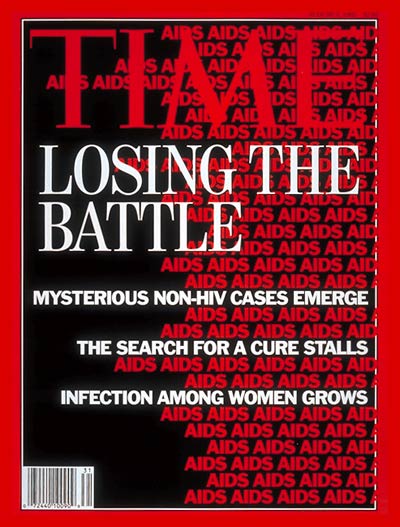

Invincible AIDS by Christine Gorman, Aug. 3, 1992

As the ’90s began, the hope that modern science could quickly conquer AIDS began to fade:

Wars are usually launched with the promise of a quick victory, with trumpets primed never to sound retreat. And the campaign against AIDS was no exception. Soon after researchers announced in the mid-1980s that they had discovered the virus that causes AIDS, U.S. health officials confidently crowed that a vaccine would be ready in two years. The most frightening scourge of the late 20th century would succumb to a swift counterattack of human ingenuity and high technology.

But no one was making any victory speeches last week in Amsterdam, where more than 11,000 scientists and other experts gathered for the Eighth International AIDS Conference. The mood was somber, reflecting a decade of frustration, failure and mounting tragedy. After billions of dollars of scattershot albeit intensive research and halfhearted prevention efforts, humanity may not be any closer to conquering AIDS than when the quest began.

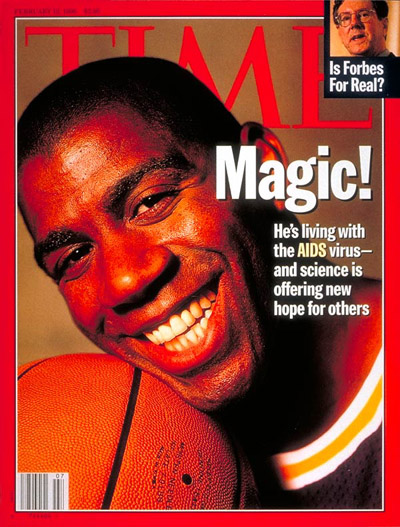

As if by Magic by Steve Wulf, Feb. 12, 1996

For more than a decade, AIDS had been a death sentence — but suddenly survival had a celebrity face. The NBA’s Magic Johnson was back in action:

If there was a bittersweet feeling to Johnson’s return last week, it came from the realization that his exile from the game had been largely unnecessary. When Magic announced to the world on Nov. 7, 1991, that he had contracted the AIDS virus, it seemed to many that he was pronouncing his own death sentence. Michael Cooper, a teammate at the time, left the press conference crying. Johnson had to quit basketball then, supposedly for the sake of his own health and definitely for the peace of mind of his peers. He made cameo appearances, first at the 1992 N.B.A. All-Star Game and then as a member of the USA’s Dream Team in the Barcelona Olympics, but when he tried to make a comeback in the fall of ’92, the fears of some outspoken N.B.A. players forced him to call it off.

But so much has happened in four years, in both AIDS research and AIDS education.

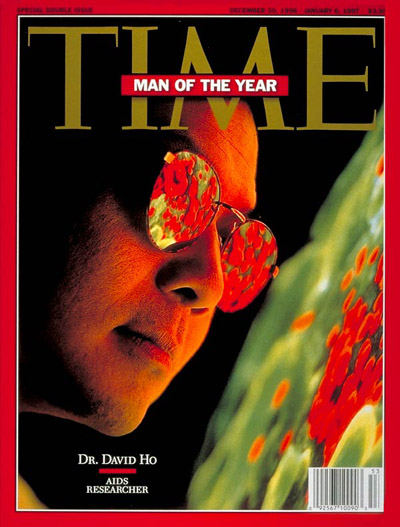

Hope With an Asterisk by Richard Lacayo, Dec. 30, 1996

In 1996, TIME named Dr. David Ho, an AIDS researcher, the Man of the Year — and, in a series of accompanying stories, explained why. That year, a cocktail of three drugs had changed what it meant to be an HIV patient:

In the history of the epidemic, there has never been a moment as intricate as this one. AIDS once again, as in the first years after it appeared, presents a predicament so new that no one is sure how to talk about it. When we say protease inhibitors work, what do we mean? Whom do they work for, how well and for how long? The only thing we know with certainty is that the conventions of language and sentiment that fit an earlier moment of AIDS, meaning all the years when death was at the end of every struggle, are unsuited to this one, when nothing is a foregone conclusion. Something powerful is happening. The new prospects for effective treatment insist that despair is an outmoded psychological reflex. Yet among people who live with AIDS, optimism is a suspicious character. Too many bright hopes of the past didn’t pan out. So this is a moment in which, for anyone with feeling and judgment, feeling and judgment are unsettled.

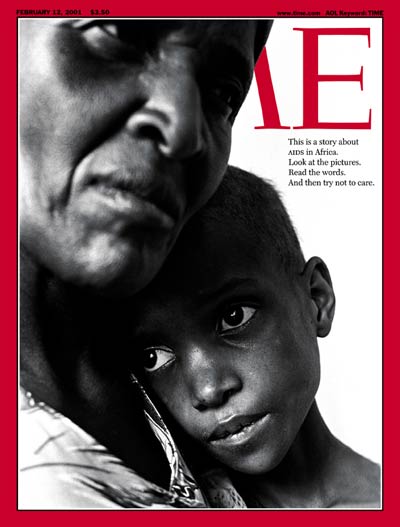

Death Stalks a Continent by Johanna McGeary, Feb. 12, 2001

In the U.S., the possibility was on the horizon: AIDS could be perhaps become a manageable chronic illness, or at least a rare disease rather than a plague. But that hopeful attitude was not a worldwide phenomenon, as a lengthy and moving cover story about African patients made clear:

AIDS in Africa bears little resemblance to the American epidemic, limited to specific high-risk groups and brought under control through intensive education, vigorous political action and expensive drug therapy. Here the disease has bred a Darwinian perversion. Society’s fittest, not its frailest, are the ones who die–adults spirited away, leaving the old and the children behind. You cannot define risk groups: everyone who is sexually active is at risk. Babies too, unwittingly infected by mothers. Barely a single family remains untouched. Most do not know how or when they caught the virus, many never know they have it, many who do know don’t tell anyone as they lie dying. Africa can provide no treatment for those with AIDS.

The End of AIDS by Alice Park, Dec. 1, 2014

The current issue of TIME presents pretty much the opposite picture from the one seen a mere three decades earlier. Whereas the syndrome’s first mentions were full of confusion and fear, today’s AIDS story — the tale of a program in San Francisco that aims to get everyone who’s positive onto medication — is about control and opportunity:

More than three decades later, the disease has killed over 650,000 Americans, and the HIV/AIDS landscape, thankfully, has changed. At its peak, there were 50,000 deaths from the virus per year; now the number is 15,000. Lately, the rate of new HIV infections has stabilized at about 50,000 annually, and more than 1 million people in the U.S. are now living with an HIV diagnosis.

Those trends are making it possible for public-health experts to shift the conversation toward reducing, and even eliminating, HIV infections. More people are living with the virus–successfully controlling it with medication–and far fewer have the immune-system crashes, cancers and infections that can come with full-blown AIDS.

And the face of HIV today is a world away from the gaunt faces and wasted spirits brought to life in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America and by Tom Hanks in Philadelphia. The reality is that it’s now possible to live, for nearly an average lifetime, without any obvious physical evidence of an HIV infection.

Read more: The Photo That Changed the Face of AIDS

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com