Even in the absence of a deal, word that talks between Iran and six world powers will continue for another seven months make plain a startling new reality: Iran and the United States now need each other.

That has been true for three decades, of course, but during that time what each found in the other was a reliable enemy. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the ayatollahs who took control in Iran built their entire world view around opposition to the United States, which had propped up the Shah the masses sent packing (and helped engineer a coup against an elected Iranian government in 1953). The presence of the Great Satan allowed the mullahs’ vision to emerge – of a world defined by the teachings of Islam, as interpreted by themselves alone, and free of “Western toxification.” From the U.S. side, the 444-day takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, and holding of 52 American hostages, has made the Islamic Republic the country’s go-to villain for more than a generation.

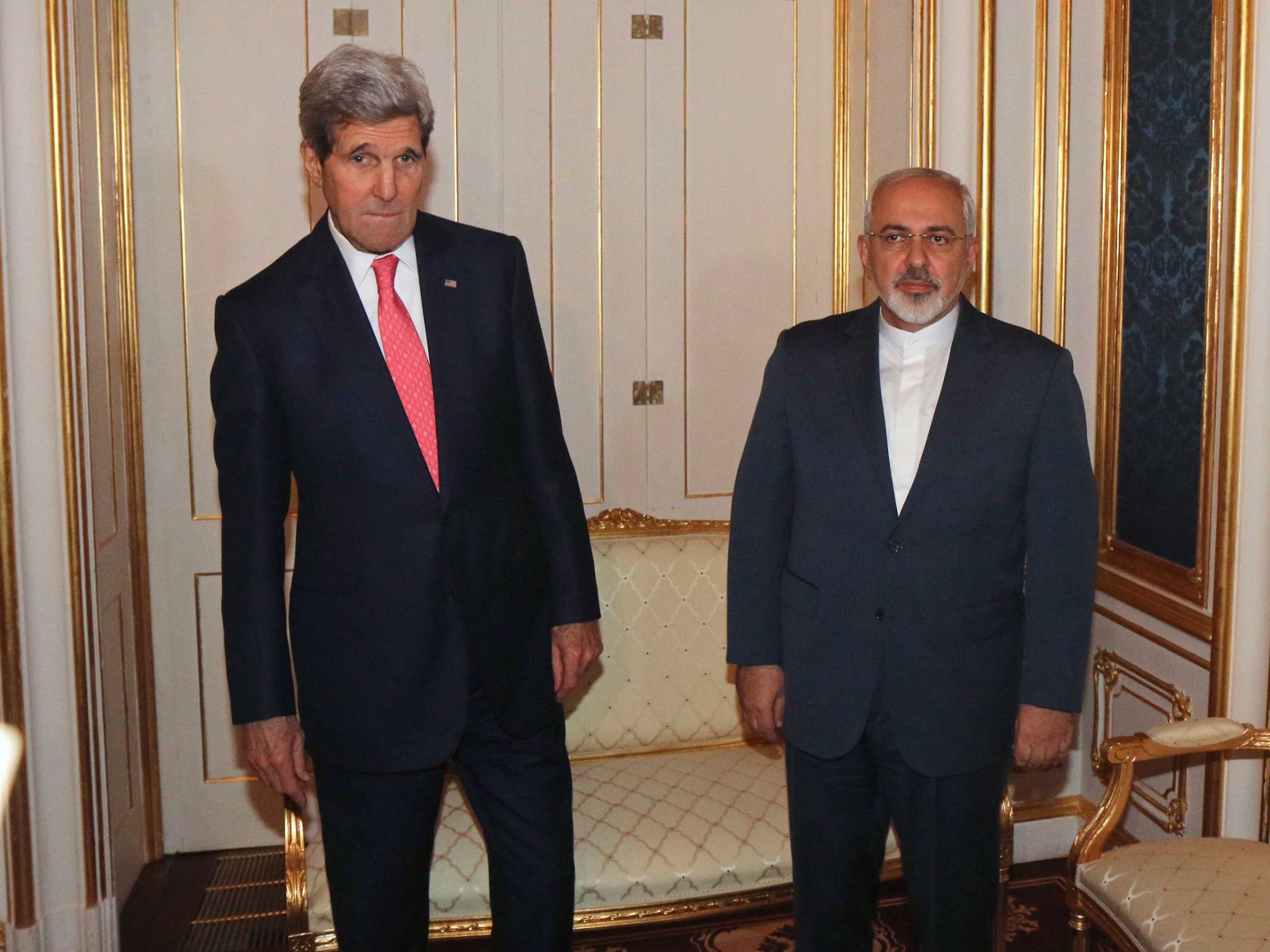

But grudges aren’t all there is to politics. Interests often trump feelings, and Tehran and Washington share a deep interest in reconciling the future of Iran’s controversial nuclear program.

The stakes for the U.S. are plain enough: Barring Iran from the means to develop a nuclear weapon undetected would not only keep a doomsday weapon from a historically radical regime, but also prevent a nuclear arms race in the world’s most reliably volatile region. And now that U.S. troops are back in Baghdad, and poised to remain in Afghanistan past the original Dec. 31, 2014 deadline, the Obama administration needs a clear foreign policy “win” more than ever.

Iran’s interests are not hard to see either – at least some of them aren’t. It wants to avoid being drawn into conflict, and, more immediately, wants relief from the devastating economic sanctions that Obama marshaled to coerce Tehran to the bargaining table. In an economy 80% controlled directly by the state, the estimated $100 billion lost so far has been a body blow to the regime. Among the losers is the financially rapacious Revolutionary Guard, an ideological military wrapped up with economic interests. Iran’s treasury is also stretched supporting its Hizballah and its ally Syria in that country’s civil war while oil prices plummet.

Iran may be wondering whether it even needs to become a nuclear state. It is coming off a string of battlefield successes, including a little-noticed takeover of Yemen by the Shiite al-Haouthi tribe supported by Tehran, and is fighting the Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) in Iraq, where it wields huge influence. “We in the axis of resistance are the new sultans of the Mediterranean and the Gulf,” the Iranian analyst Sadiq Al-Hosseini said on state television Sept. 4. At this rate, getting The Bomb might seem like an unnecessary hassle.

At the same time, pressure for a deal only builds among Iran’s youthful population—over 60% of whom are aged 30 or under—and the mullahs fear their own people as any government does. That’s been in evidence since the surprise first-round election of Hassan Rouhani as president last year, on a platform of ending Iran’s international isolation, and could be seen as recently as mid-November, when hundreds of thousands of young people gathered to mourn a pop singer, in a potent reminder of the lasting potential for spontaneous demonstrations and the appetite of youth for connection.

“If that is not a big referendum on the status quo, I don’t know what is,” says Abbas Milani, head of Iranian studies at Stanford University. “Things like this happen on a daily basis, and I think Rouhani has recognized that the society has already moved.”

Other observers see the glass as half empty, or even less. Ray Takeyh, who follows Iran for the Council on Foreign Relations, agrees that, unlike previous negotiations, the mullahs have signaled ownership of the process: “This negotiating team is not called ‘the negotiating team,’” he notes. “It’s called ‘children of the Revolution.’’’ But whatever interests the U.S. and Iran may share, he says, are overwhelmed by those they don’t.

“Arms control agreements are based on trust,” Takeyh says. “Each side has to trust the other. When they don’t trust each other, they both demand reversible steps that prevent years-old enmity from evaporating. I think that’s the reason you can’t get an arms control agreement. I think they both want to solve the nuclear issue, but at this point on terms that are unacceptable to each other.”

Still, they are talking, and holding to the terms of their previous agreement for seven more months. That might not be long enough to repair three decades of mistrust — but it might yet be enough to find that elusive patch of common ground on which to build a deal.

Read next: Iran Nuclear Talks to Be Extended Until July

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com