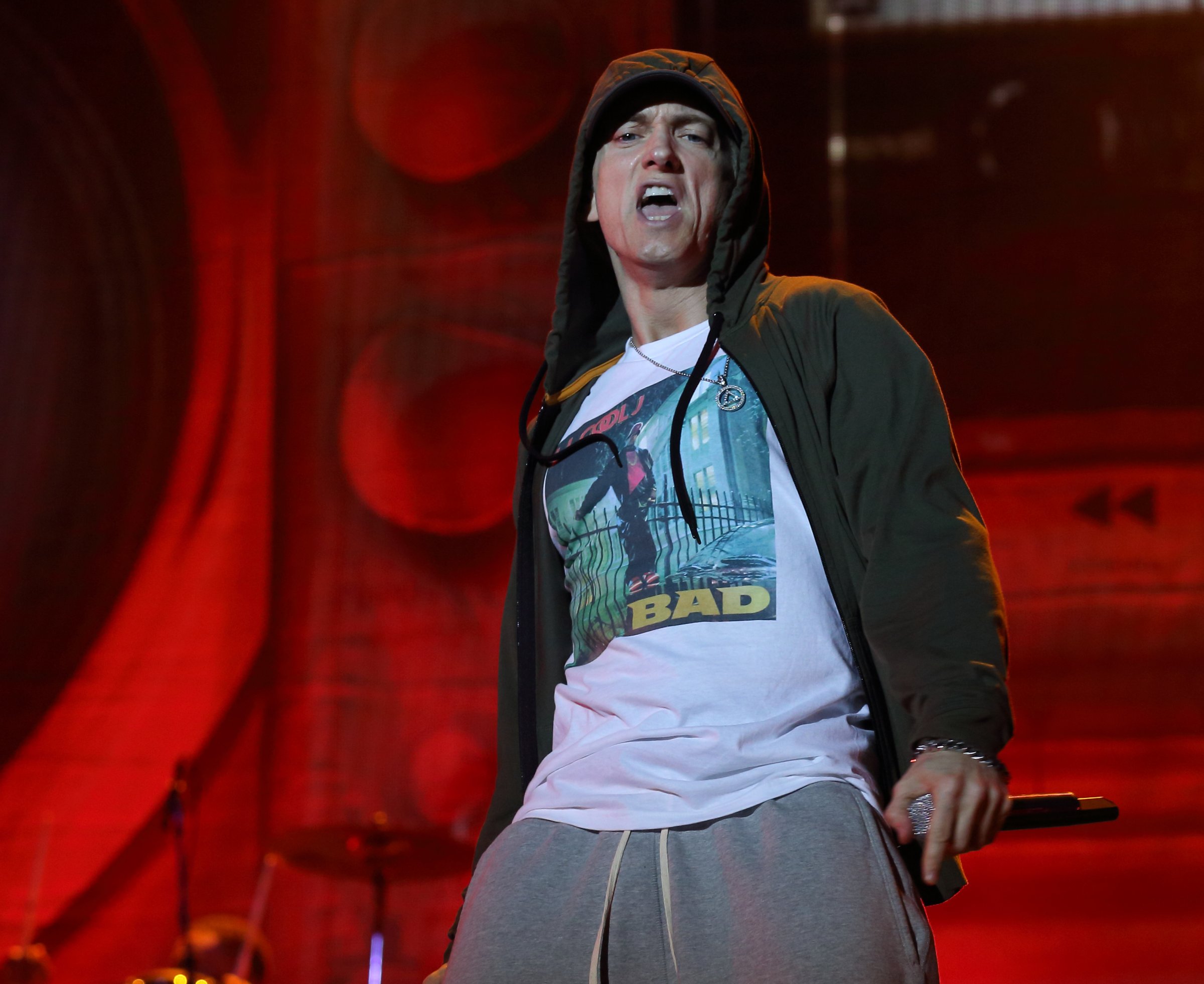

Eminem’s first major album, The Slim Shady LP, came out in 1999, kicking off a career that would seem to have burned too brightly for any claims on longevity. And yet on Nov. 24, the defining artist of the early 2000s is celebrating his sustained success with the release of Shady XV, a new album commemorating fifteen years of his label Shady Records and assisted by numerous featured guests.

The decade-and-a-half since Shady have been up-and-down for the Detroit rapper – he went on hiatus in the mid-2000s owing to personal travails, about which he went on to wax lyrical in well-received recent albums. But Eminem seems, in a larger way, removed from the cultural context of the past 15 years. In his early tracks, like “’97 Bonnie and Clyde” or “The Real Slim Shady,” Eminem was provocative in a manner that was all about cultural context. Today, he’s just boring.

The Eminem who recorded music from 1999 to 2004 or so was a self-styled nihilist, rebelling against every standard of propriety imposed by, as he put it, white America. He rose to fame in the same way Marilyn Manson had a few years earlier: By presenting kids and teens with a release valve to channel all of their anger, and by presenting parents with a unified threat that could mean anything. To kids, Eminem, with lyrics mocking other stars’ promiscuity or, most memorably, mocking propriety with the image of him killing his wife and disposing of her body, was an exciting provocateur, taking their anger about the lack of control they had in their lives to a new, unforeseen level. To their parents, he was public enemy number one. Both receptions combined to make Eminem the media story of the decade.

His music now, though, is pretty anodyne, owing in part to the sources from which he grows inspiration. It’s impossible to imagine his recent number-one single “The Monster” launching any teen rebellion; with its bouncy beat and fashion-magazine-interview lyrics about how Eminem is challenged to remain authentic in the face of fame, it’s practically lite-FM ready. “Love the Way You Lie,” his recent hit humanizing both sides of an abusive relationship, was muddled but well-meaning.

But it’s hardly an age of EmLightenment: For every song Eminem releases that goes to number-one on the back of amiable thoughtfulness, there’s another that’s nastier than anything he’s ever released. In a recent group freestyle video, the rapper referenced a popular current singer and a major recent abuse scandal: “I’ll punch Lana Del Rey right in the face twice, like Ray Rice in broad daylight in the plain sight of the elevator surveillance.”

This rap, which also includes a reference to beating lesbians that uses a coarse colloquial term, comes on the heels of a mini-scandal last year in which Eminem was called to account for his use of a common slur against gay men in his song “Rap God.” Eminem claimed, then, that he does not think of the term as a reference to sexuality at all, citing rap-battle culture in his native Detroit. “It was more like calling someone a b—- or a punk or a—hole,” he said. “So that word was just thrown around so freely back then. It goes back to that battle, back and forth in my head, of wanting to feel free to say what I want to say, and then [worrying about] what may or may not affect people.”

This is disingenuous at best. Eminem, throughout his career, has existed specifically as a counterargument to ideas of propriety, including those governing how to treat gay people; in a verse featured on a Nicki Minaj song, Eminem used the same antigay slur in threatening to “stick it to ‘em like refrigerator magnets.” Is this, too, just an attempt to intimidate unseen opponents, along with the many instances early in his career of violently anti-gay rhetoric?

Eminem is in a tricky double bind. He’s popular enough, as an idea and as a musician, to continue working, and to continue selling his songs. He’s not just a working artist but a tremendously successful one, especially as concerns the songs in which he’s juxtaposed by a soothing woman’s voice on the hook and in which he finds some sort of moral uplift. But what initially made him popular, at the start of his career, is out of style. When Eminem attempts to channel rage, he’s met with the social-justice-aware internet (which is hardly wrong) — and he would seem, too, to fall on deaf ears among both children and parents.

American parents hardly need a unified threat whose influence they can fear: Literally all of American culture has grown more sexually explicit, and more violent, in the past fifteen years, even as the subtler strains in Eminem’s music, the everpresent misogyny and homophobia that used to go uncommented-upon amid all the more obvious violence, now raises eyebrows. Eminem’s trying to be the baddest man in a game that now extends across all of culture, and he’s not proving successful in the attempt. As for the kids? Like it or not, they’re listening to “Same Love.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com