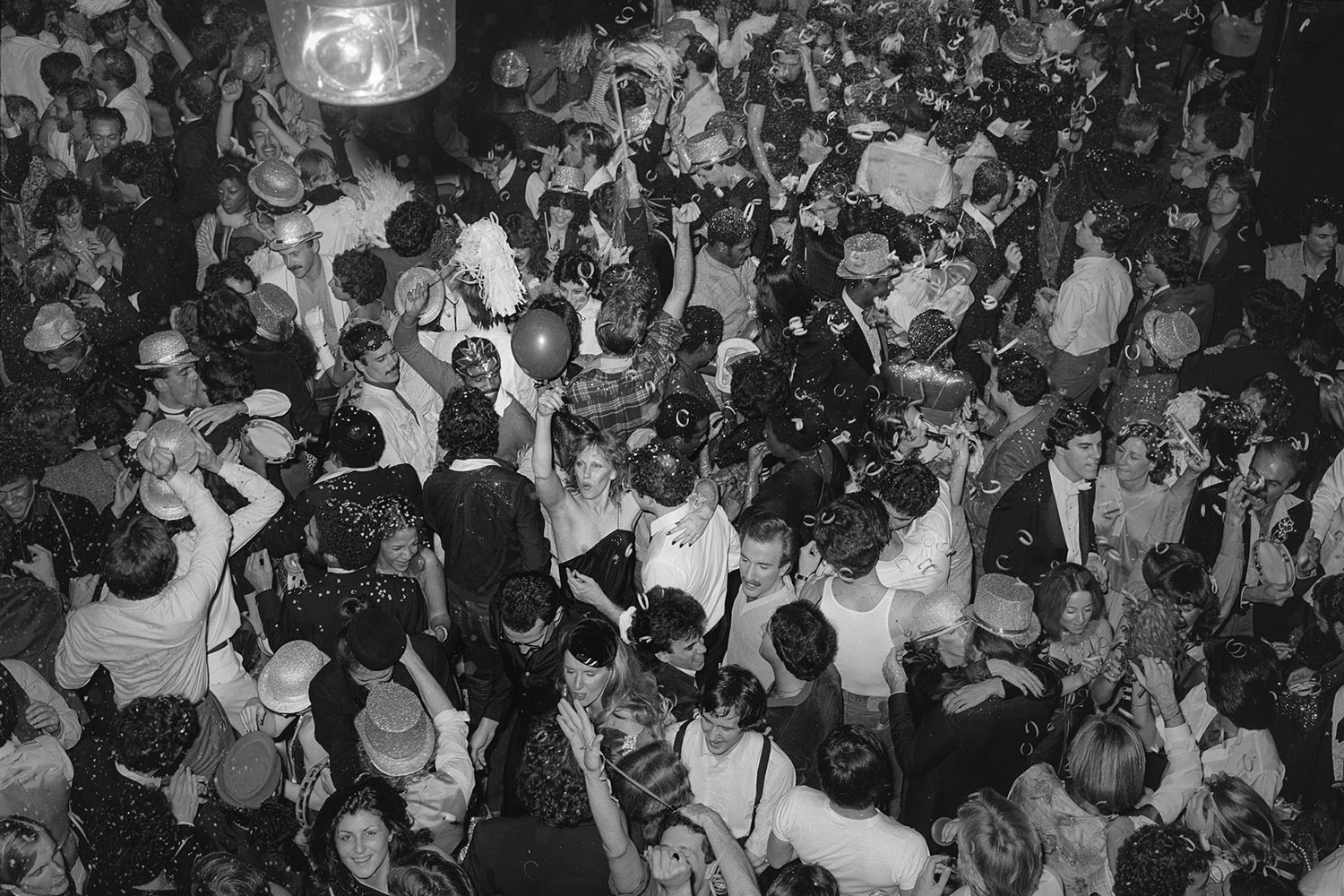

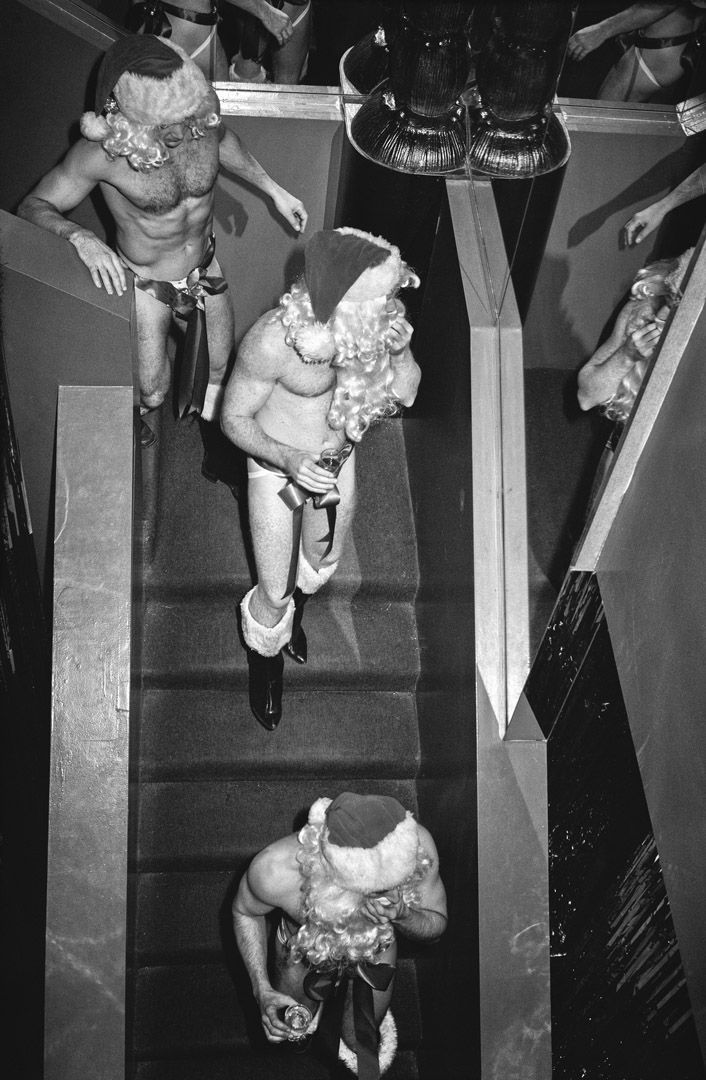

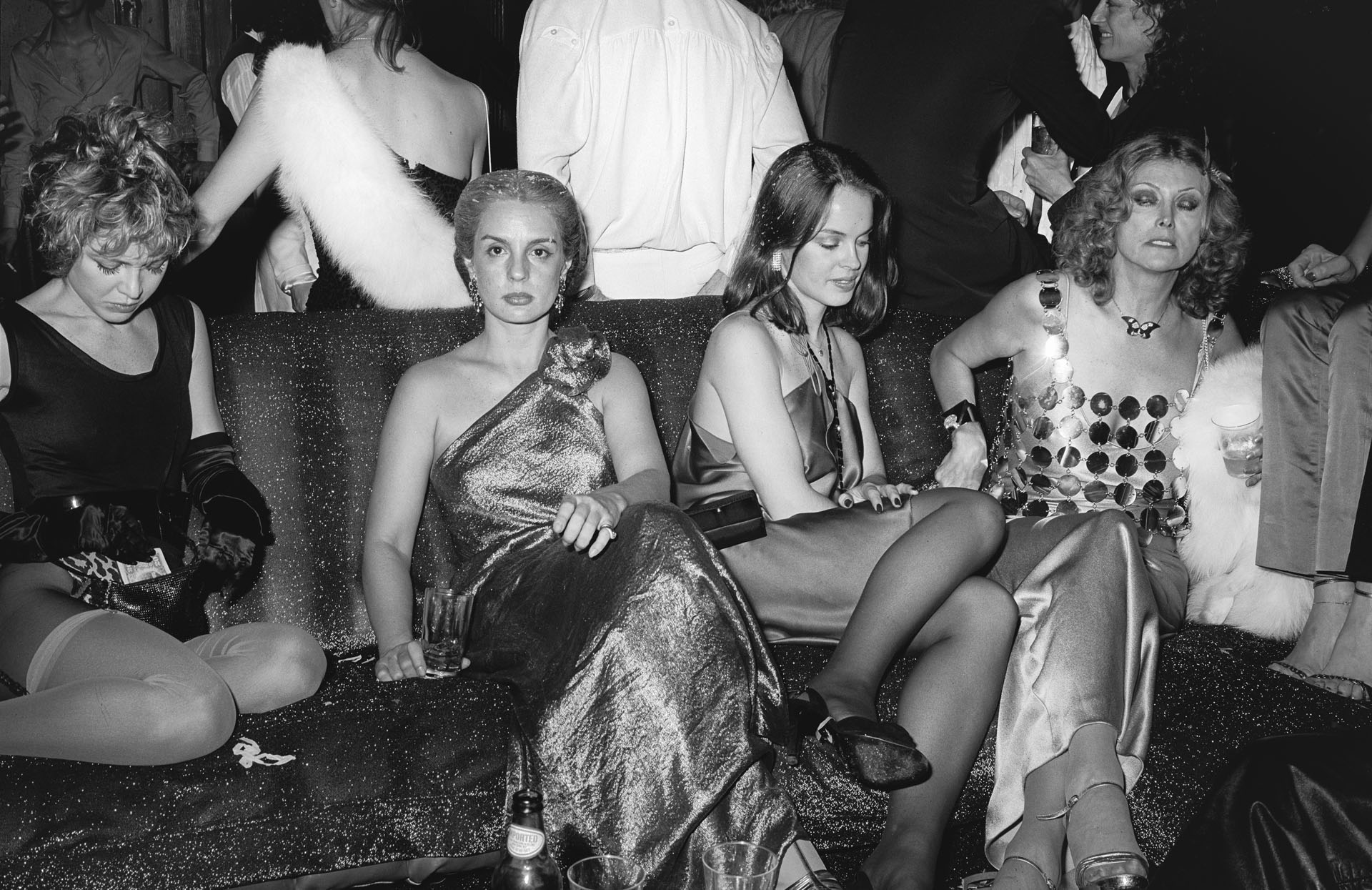

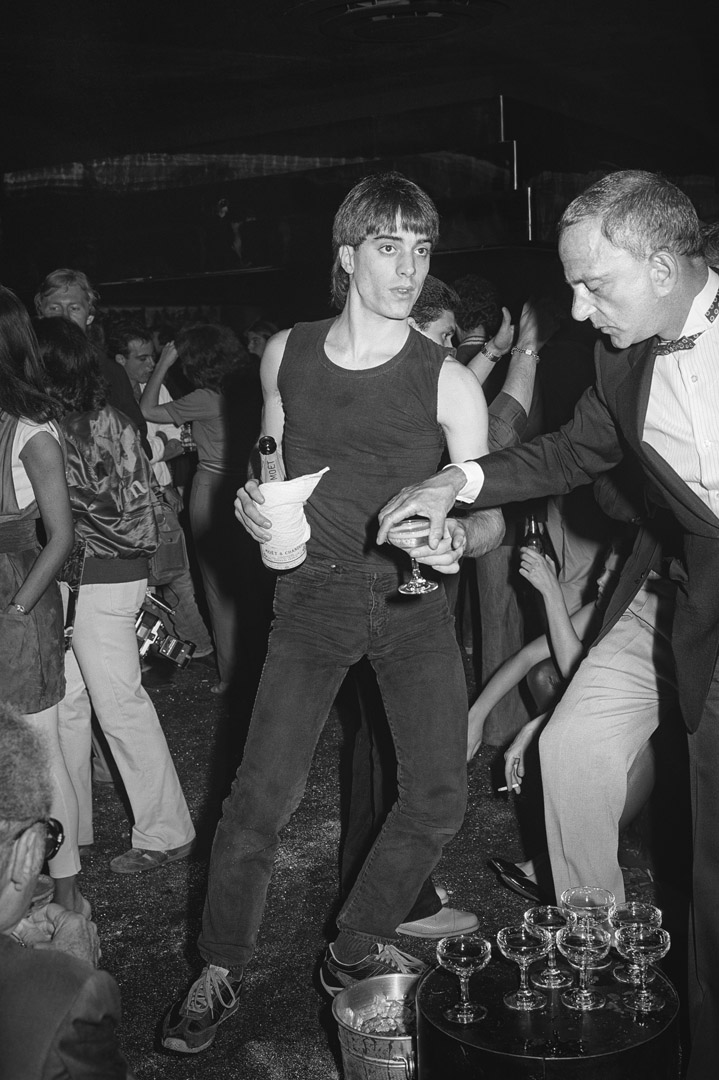

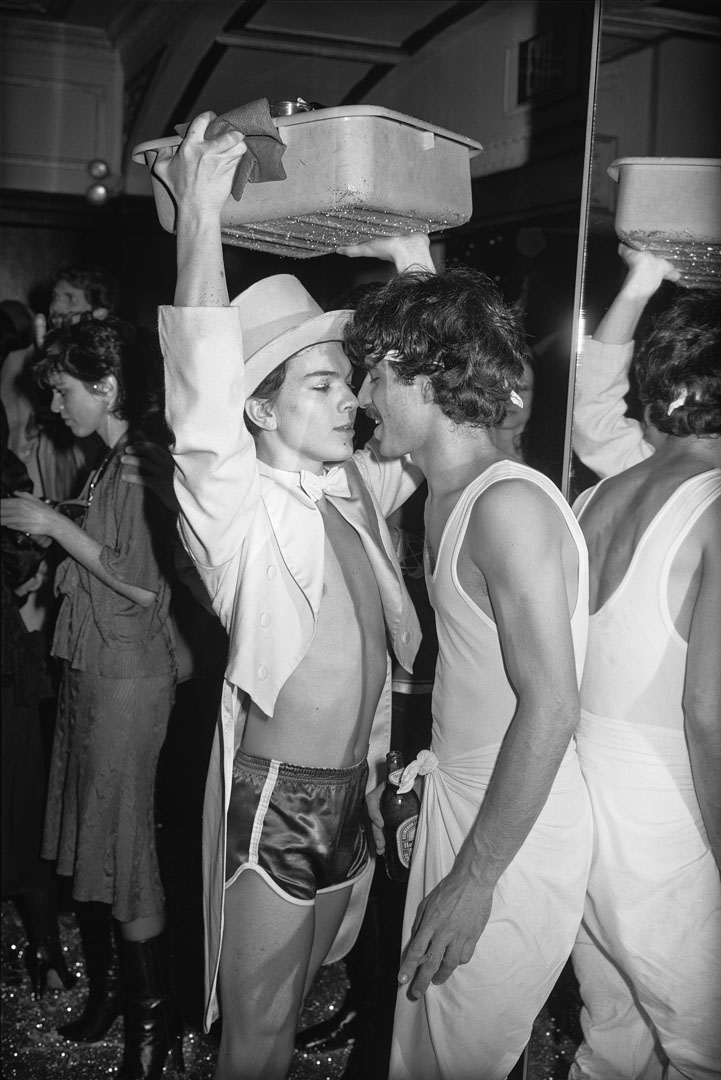

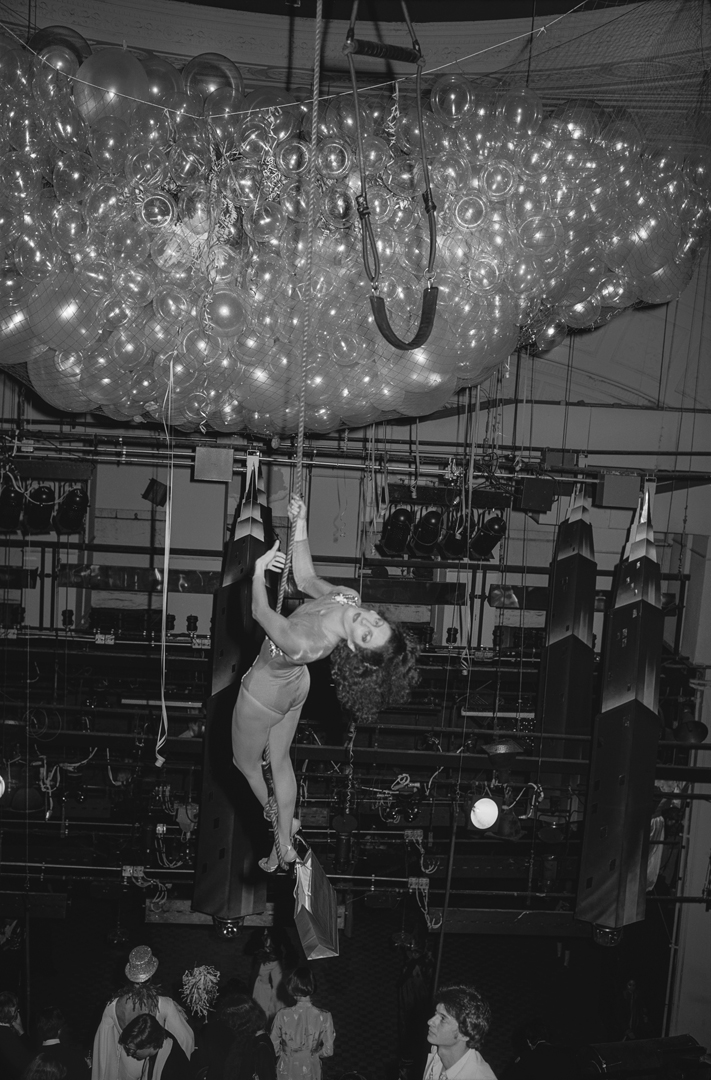

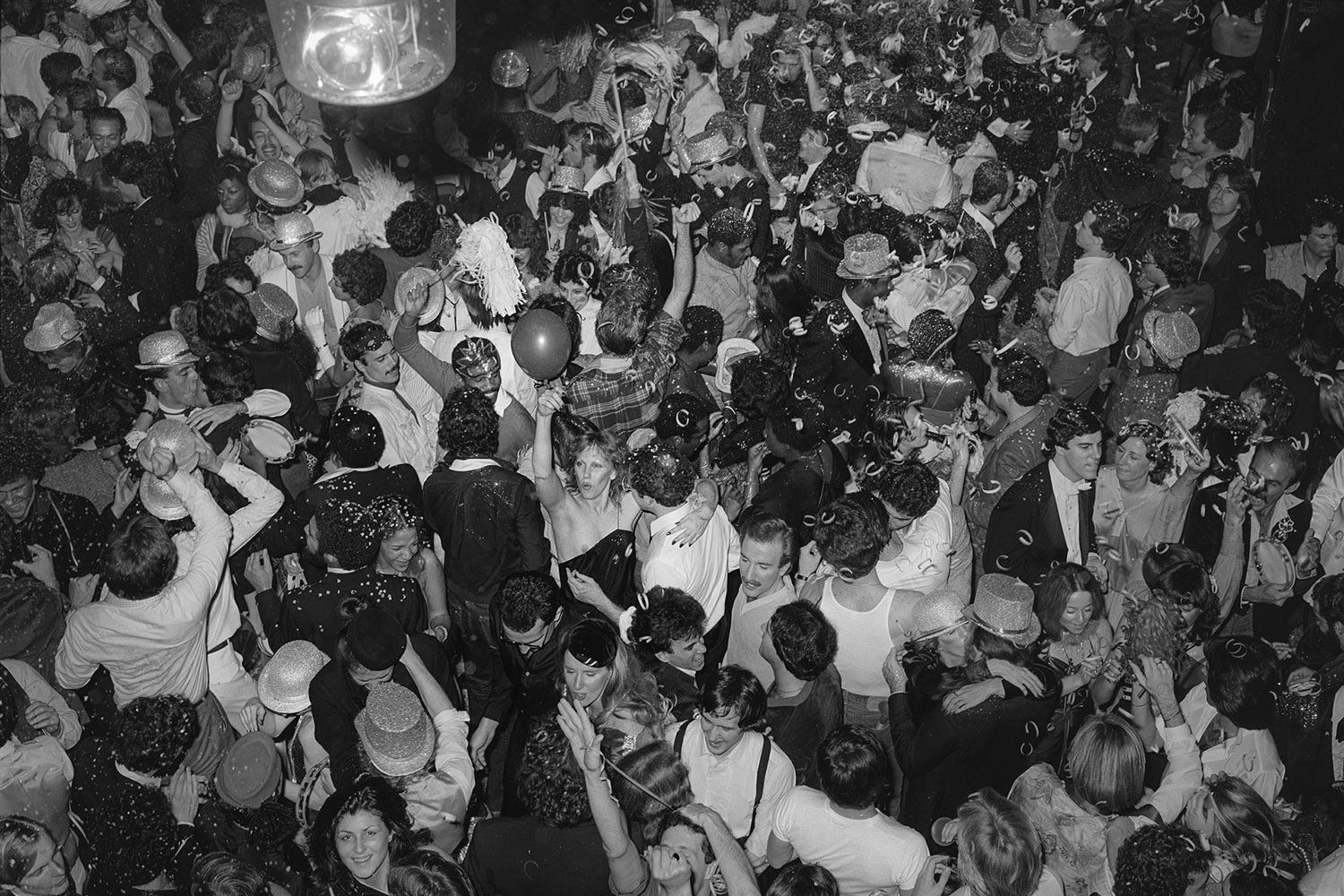

In the history of New York nightclubs and the social scene, Studio 54 is legendary. During its most popular years between 1977 and 1981 it was the place to see and be seen and drew thousands that regularly included famous models, actors, rock stars, artists, fashion designers, politicians and even a few ballet dancers. Photographers were common although mostly paparazzi searching out only the rich and famous, but a few entered the club with different aspirations: that of transcending the obvious and transforming the superficial flash and glitter into something akin to poetry. Tod Papageorge was one of those photographers.

Papageorge is perhaps more commonly known as an educator, having spent three and a half decades heading and teaching the prestigious Masters program in photography at the Yale School of Art where his students were the likes of Gregory Crewdson, An-My Lê, Philip Lorca diCorsia, Katy Grannan, Justine Kurland and hundreds of others. His teaching credit aside, Papageorge is a photographer first and foremost who has published three volumes including; Passing Through Eden (Steidl, 2007) and American Sports, 1970 (Aperture, 2008).

Sixty-six of his best nightclub images form this new book from Stanley/Barker called Studio 54. Here, Papageorge speaks to Jeffrey Ladd.

TIME LightBox: Might I assume that you didn’t have the original impulse to go to Studio 54 for your own entertainment? Were you gaining access as a ‘photographer’ or just as a party-goer?

Tod Papageorge: A friend of mine, Sonia Moskowitz Gordon, was doing celebrity photography then, and was well-known and equally well-liked at Studio 54. She asked me if I’d be interested in photographing there and I jumped at the chance. Needless to say, though, I wasn’t a partygoer while I made the pictures. Photography is difficult to do well even with absolute concentration. Without it, mixing work and play, it becomes impossible, at least for me.

LightBox: Within the couple years these photographs span, would you be going frequently or was this book the fruit from a couple very successful evenings?

TP: My unreliable memory says, “neither.” I certainly wasn’t going to Studio 54 a lot. My best guess is I photographed there between a half-dozen and a dozen times, certainly not more.

LightBox: Had you gone to other clubs as well?

TP: I photographed in Roseland once, and also, I believe, at the Waldorf-Astoria—in any case, at a place where young Latin-America women in skimpy bathing suits were competing in a beauty contest.

LightBox: Was Studio 54 itself an attraction as a place or had you thought ‘it’ (whatever that is that draws one to photograph) might be happening in any number of other clubs?

TP: Again, I showed up there originally because I was offered the chance. But it was obvious from that first night that Studio 54 was a world, and institution, onto itself. It had originally been a theater, a roundabout space overlooked by a balcony, which created an up-and-down geography that, through some kind of alchemy, abetted the sense of frenzy that the music and audience-dancers were generating on the dance floor.

LightBox: You were using very similar tools as Brassaï had photographing Parisian nightlife in the 1930s (a 6×9 medium format camera and flash). Was Brassaï an inspiration for your own exploration of New York nightlife?

TP: Yes, as I say in my brief text in the book, Brassaï was my direct inspiration. A great artist, great writer, and great thinker. All in one small man from the Transylvanian mountains.

LightBox: Most photographers in nightclubs are paparazzi types but there are a few artists of your generation who also worked in such environments, Larry Fink being one. A few of his photographs from 1977 taken in Studio 54 were collected by MoMA and later showed up in his book Social Graces (Aperture, 1984). Had you been aware of his work?

TP: I’d seen Social Graces, of course, but hadn’t noted where Larry had made his nightclub pictures. I remember seeing him at Studio 54 one night while I was working there, though, and being curious about the way he was using his flash, away from the camera. But that was it. We were after very different things, then and later, there and elsewhere, the chief one being that, at least in the photographs you’re asking about, he was zeroing in on celebrities.

LightBox: Is this work some of the first where you were using the medium format 6×9 camera?

TP: I was also photographing in Central Park virtually every day then, using the same gear I brought to Studio 54, including the flash (which, in the park, served as fill-in light). So it’s accurate to say that this was the first time I used the 6×9 intensively or, more accurately, exclusively, since I’d bought an earlier iteration of the camera in 1973, when I tried it out on a cross-country trip. Landscapes only, though, with my Leicas reserved for everything else.

LightBox: Due to the nature of Studio 54, celebrities appear a few times in your photographs. Garry Winogrand once said that certain things in the world make the photographic problem more difficult (like monkeys), are celebrities one of those things too?

TP: Celebrity played no part in what I photographed at the club, or the way I did it. Again, because he did photograph them, I’d be curious to hear Larry Fink answer this question. Particularly when, as has happened a few times lately, I see someone who’s looking at my pictures at 54 spot one of the rare celebrities in them—Brooke Shields or Carolina Herrerra, for example—and then proceed to treat the particular photograph as little more than a vessel holding a star. Which has led me to think that perhaps Garry’s observation applies even more to famous people than it does to monkeys. In photographs, one monkey is all monkeys; Brooke Shields is only Brooke Shields, unique.

LightBox: You have been publishing books of mostly older work made in the 1960s to 80s. Until you recently published them, had you thought of the work at the time as just a continuum that could be divided later into loose subjects or were these conceived as ‘projects’ then as well?

TP: I ‘d like to start my answer by saying that I’ve been working in color with digital Leicas in Rome for the past few years (when I had the occasion and time and, sometimes, support to get there), and that I’m very excited about the photographs. But you’re correct in pointing out that my published books have concentrated on work I did a while ago, in some instances a great while. However, the ways in which they came into being were varied. For example, my sports book was a project, done on a Guggenheim Fellowship within a brief period of time. But Studio 54 and Central Park, which I worked on simultaneously, constituted together an elemental continuum: night and day. So, I suppose the shaping frame varies, but the overarching value is photography, and the pleasure it gives to do it.

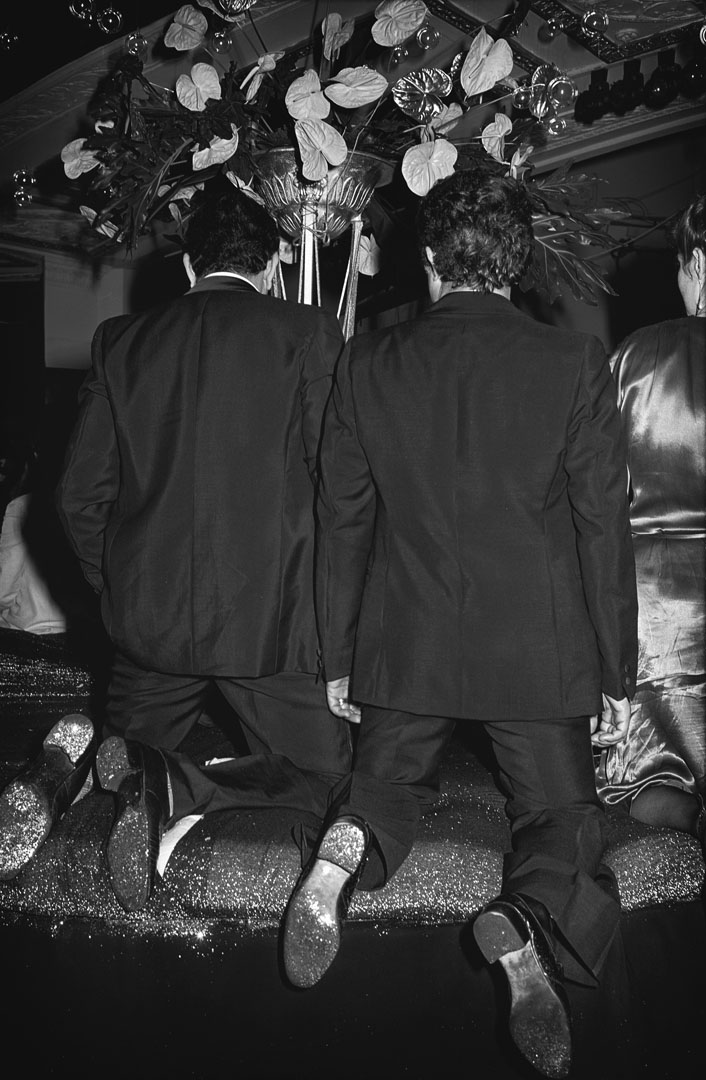

LightBox: In making this book, had you an idea behind the sequencing? As the book progresses full intoxication is implied by the body language of the people, etc.

TP: Gregory Barker, the publisher of the book (with his wife, Rachel) came up with the idea, which I have to admit I originally thought was too obvious. As it turned out, though, I quickly saw that I was wrong to react that way: the photographs are so rich in detail and, from one to the next, active in their form, that anyone opening the book is forced to become a kind of slow reader, inoculated against the obvious.

I also think that having only three picture “templates” for the two-page spreads—i.e., double spreads; a vertical picture on a right-hand page, and single-page horizontals always appearing in pairs—lends a counterweight to the churning energy of the pictures themselves.

LightBox: The title of the book, Studio 54, implies in a way that this is ‘about’ the nightclub (like a document) but the pictures are really about, among other things; sex, decadence, body language, fashion that implies wealth, and a certain amount of outlandish spectacle. I know you are adverse to photographs being called documents so is there a conflict of calling this Studio 54 and your beliefs in photographs being fiction?

TP: No. We’re talking about photography here (at least as I understand and want to employ it): bound by fact, aspiring to poetry—or fiction, if you will. And, anyway, by now it seems to me that the phrase “Studio 54” inspires fantasy or reverie more than any other kind of response. Obviously, though, each individual viewer has to decide for him or herself whether the book works (or doesn’t) as a document or as a photographic song. I’d guess (and hope) that more will thrill to it, as they thrill to a poem or film or Champagne, than will feel dropped on the pavement outside a nightclub in midtown New York, circa 1978.

Photographer Tod Papageorge is a two time Guggenheim Fellowship and National Endowment for the Arts Visual Artists Fellowship recipient. His work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com