The calls, overwhelmingly, were for peace. But the result was anything but.

A St. Louis County grand jury declined to indict Ferguson, Mo., police officer Darren Wilson for fatally shooting Michael Brown, an unarmed African-American teenager, after an encounter in the St. Louis suburb on Aug. 9. The decision, announced Monday evening, means Wilson will not face criminal charges in a case that ignited a national debate about race, privilege and policing in America.

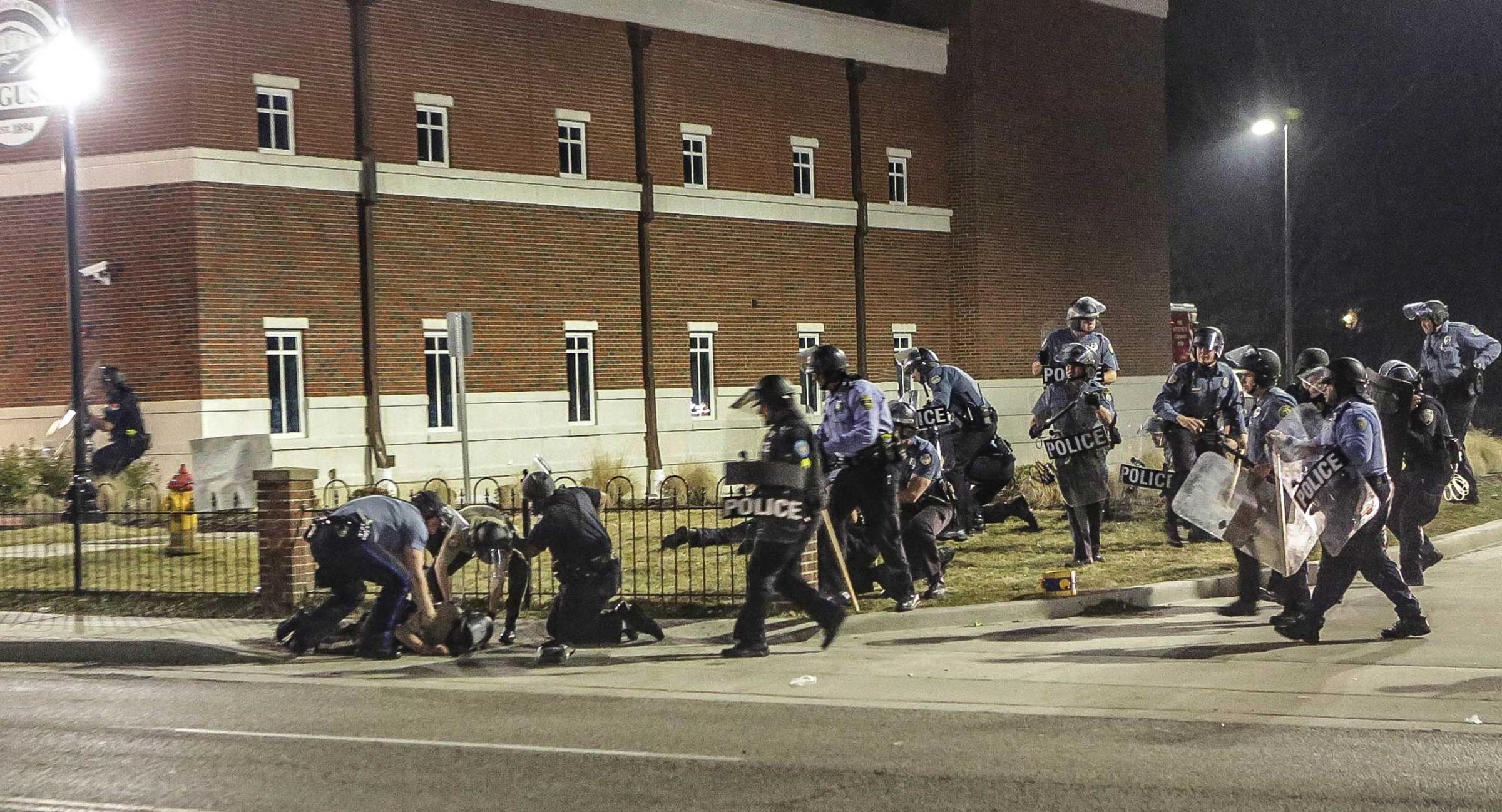

The announcement immediately revived the frustration of protesters who filled the streets of Ferguson for weeks this summer, leading to a renewed wave of clashes with riot gear-clad police. As the news spread, demonstrators blocked the street in front of the Ferguson Police Department, chanting obscenities and throwing objects at officers.

As the night wore on, the demonstrations erupted into violence. In an echo of the worst of the earlier unrest, businesses were set on fire and looted and law enforcement fired smoke bombs and tear gas in an attempt to disperse the angry crowds. The sting from the chemical hung in the air for blocks, and the sidewalks and parking lots near the Ferguson Police Department were filled with people washing out burning eyes and vomiting in gutters.

Ferguson Ignites With Violence After Grand Jury Decision

It was precisely the response many feared but never wanted. The days leading up to the decision were a drumbeat of pleas for peace, with clergy, local residents and even President Obama urging crowds to channel their anger into something more productive. The Brown family echoed those calls in a statement after the decision. “We are profoundly disappointed that the killer of our child will not face the consequence of his actions,” the statement said. “While we understand that many others share our pain, we ask that you channel your frustration in ways that will make a positive change. We need to work together to fix the system that allowed this to happen.”

Protests spread to cities across the U.S. late Monday, with thousands rallying in cities from New York to Los Angeles. Demonstrators in Oakland, Calif. flowed onto the westbound lanes of Interstate 580, temporarily blocking traffic, but the majority of protests outside of the St. Louis area remained mostly peaceful.

Speaking from the White House about an hour after Wilson’s fate was made public, the President said he hoped the incident could force the nation to address the larger sense of mistrust between African-Americans and police.

“We need to recognize that the situation in Ferguson speaks to the broader challenges we still face as a nation,” he said. “In too many parts of this country, a deep distrust exists between law enforcement and communities of color.”

Obama, too, called for a peaceful response, yet as he spoke television news networks aired split-screen footage of police deploying tear gas and smoke grenades at demonstrators.

The President’s wishes went unheeded, at least in the immediate aftermath. That the grand jury’s decision was revealed after dark surely didn’t help.

See 23 Key Moments From Ferguson

In a lengthy news conference announcing the grand jury’s decision, St. Louis Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch painstakingly described the events leading up to Brown’s death. The grand jury, he said, heard contradictory testimony from eyewitnesses, some of whom changed their stories to reflect the evidence. He later released thousands of pages of documents reviewed by the grand jury including photos of Wilson taken at a hospital after the shooting that appear to show bruising to his neck and face.

“As tragic as this is, it was a not a crime,” McCulloch said.

Preparing for the Worst

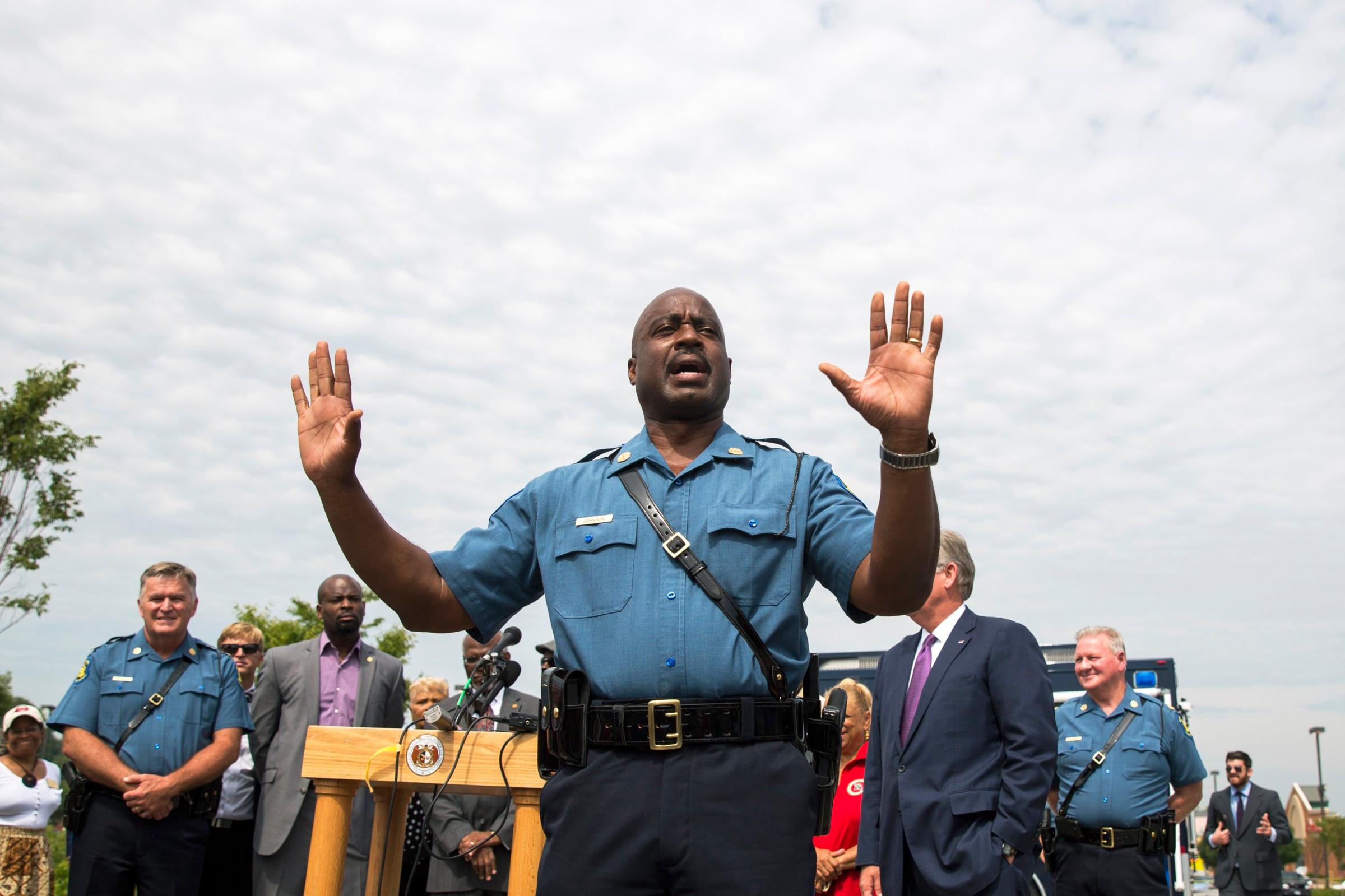

Even before the decision was announced, police had gone to great lengths to prepare for protestors’ frustration to spill over. City, county and state officers, as well as National Guard, were marshaled under a unified command as part of a state of emergency that Missouri Governor Jay Nixon imposed in advance on Nov. 17, citing “the possibility of expanded unrest.” The atmosphere has been so charged that many area schools closed early for Thanksgiving break and Nixon reiterated his call for calm on Monday ahead of the grand jury’s announcement.

The preparations on both sides fed a sense that the first official finding in Brown’s death would inevitably generate another occasion for talking past one another, and perhaps more violence. Far from being resolved, the mistrust that marked the largely spontaneous original protests — characterized by raised arms and chants of “Don’t shoot” — had not abated. Nor had the reality that propelled Ferguson onto the national stage: the unwelcome attention African Americans routinely receive from police, and disproportionate treatment from the justice system as a whole.

In that realm, the details of the Brown case are less significant than the broader experience of many black Americans any time they encounter a uniformed officer. Outgoing U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said in September that, though he served as the nation’s top law-enforcement official, as an African-American man who has been searched unnecessarily by police, “I also carry with me the mistrust that some citizens harbor for those who wear the badge.”

In Ferguson, where the population is two-thirds black, the situation was exacerbated by the composition of a police department that had only four African Americans on a force of 53. When protests broke out, the heavy-duty military gear officers donned to confront them did nothing to diminish the impression of antagonism between police and public. Much of that armor was left over from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and distributed by the Pentagon to local law-enforcement departments. The battle gear did little to serve a police force that, like many in the U.S., is seen by minorities “as trying to dominate rather than serve and protect,” in the phrase of Yale Law School Professor Tom Tyler, an expert on law enforcement and public trust.

“This is more than Michael Brown,” area resident Rick Canamore, 50, said as he protested in front of the Ferguson police headquarters. Brown’s death “tipped the pot over, but this has been boiling for years.”

Two federal investigations are still pending. The FBI is investigating whether Wilson violated Brown’s civil rights. Separately, the Justice Department is examining the civil rights record of the Ferguson Police Department as a whole. And Brown’s family could still file a civil wrongful-death lawsuit.

After the decision, Attorney General Eric Holder reiterated that the federal civil rights investigation is distinct from the grand jury proceedings. “Though we have shared information with local prosecutors during the course of our investigation, the federal inquiry has been independent of the local one from the start, and remains so now,” Holder said in a statement. “Even at this mature stage of the investigation, we have avoided prejudging any of the evidence. And although federal civil rights law imposes a high legal bar in these types of cases, we have resisted forming premature conclusions.”

An Unusual Grand Jury Proceeding

But the fraught months following Brown’s death have been focused on the grand jury’s finding, which was both expected and atypical. Expected because a series of leaks in October revealed details that supported Wilson’s version of the encounter. These include medical reports of injuries to Wilson’s face, which officials have said occurred when Brown reached into the patrol vehicle and struck Wilson. Two shots were fired inside the vehicle, but Brown was killed after Wilson climbed out of the vehicle to pursue the 6-ft. 4-in., 289-lb. teen.

Though the leaks and a certain sense of fatalism had prepared protesters for the outcome, the grand jury’s finding is statistically rare. Ordinarily, almost every case that a prosecutor takes to a grand jury ends in indictment. At the federal level, of 42,140 grand jury investigations in 2012, only 56 targets escaped indictment, according to records provided to TIME by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. Similar figures were not available for St. Louis County grand jury investigations.

Local officials emphasized that the grand jury examining the Ferguson case had unusual leeway — though that leeway may have served Wilson. The panel, which had already been seated at the time of the Brown’s death, was broadly representative of St. Louis County, with nine whites and three African Americans. It met weekly for three months, and was presented “absolutely everything” about the altercation, said St. Louis County chief prosecuting attorney Robert P. McCulloch. The jury, which began hearing testimony on Aug. 20, reached its decision after two days of deliberations.

That meant it heard from witnesses who said Brown appeared to have had his arms up in surrender at the moment he was shot, as well as from witnesses who supported Wilson’s account that the teen attacked him, and was charging at him head-down at the time of the shooting. One of Brown’s six bullet wounds was on the top of his head.

In another departure from normal proceedings, the grand jurors did not hear a prosecutor recommend a charge and present evidence supporting it. Instead, they were offered a range of possible charges, from murder to involuntary manslaughter.

In addition, Wilson took the unusual step of testifying, which seldom happens because defense attorneys are not allowed to be present in grand-jury proceedings. But it may well have helped the officer, inasmuch as the question before jurors was whether he had reason to fear for his life.

In short, the grand jury’s inquiry proceeded very much like a trial — but in secret, as grand jury proceedings always are. That sat poorly with attorneys representing Brown’s family. The prosecutor’s office took the unusual step of recording the sessions, and released them after the decision in hopes of achieving a measure of transparency after the fact.

That might not have been possible. “If there’s no true bill,” Adolphus Pruitt of the St. Louis NAACP told TIME in September, “as a community, we are going to be thrust right back into the same discontent and civil disobedience we experienced the first time around.”

Similar vows were heard from a variety of groups that descended on Ferguson in anticipation of the grand jury’s decision. The community remained on edge despite town meetings moderated by national figures, efforts at police reform such as wearable cameras, and sometimes fumbling attempts at reconciliation by local officials. In late September, Ferguson police chief Tom Jackson apologized for leaving Brown’s body in the street for about four hours – infuriating bystanders who saw it as yet another sign of disrespect. The chief’s apology was offered to Brown’s parents, but delivered in a video aired on CNN, and distributed by a public-relations firm. Another grievance came Monday afternoon, when attorneys for the Brown family say the parents first learned that the grand jury had reached a decision when they were asked about it by a reporter.

New incidents, meanwhile, kept emotions raw. In Ferguson, where some police officers wore wrist bands reading “I am Darren Wilson,” an officer was shot in the arm while chasing two men who ran from him when he approached them on Sept. 27. And on Oct. 8, an 18-year-old African American was shot and killed by an off-duty St. Louis police officer after allegedly firing a stolen gun at him.

The protests that began the night Brown’s lifeless body fell onto Canfield Drive never really stopped. Mostly peaceful demonstrations continued day and night over the weekend before the grand-jury announcement, the rowdiness growing the later it got. A dozen people were arrested in a four-day period ending Sunday. The weather helped police, with cold and continuous rain causing protesters to disperse on several occasions, according to the St. Louis County Police Department spokesman Brian Schellman.

The ongoing protests have cast a pall over virtually every corner of the community. Area businesses report sales down as much as 80%. That many decided to board their windows as a preventative measure ahead of the grand-jury decision kept even more shoppers away. Donations to local religious groups and nonprofit organizations have been sluggish. A local food pantry’s stock is low because “people don’t want to come into the area,” says Jason Bryant, a local pastor.

For many local residents eager to see Brown’s death lead to something positive, the fallout from the grand jury’s decision will only make matters worse. “Police have hurt our people for years, for decades,” says Cassidy Jones, 42. “But this is not the answer. This is anger making more anger. It’s not good.”

— Kristina Sauerwein reported from Ferguson, Mo. With additional reporting by Alex Altman and Zeke J. Miller / Washington, D.C.; Dan Kedmey / New York City; and Katy Steinmetz/San Francisco

Read next: Ferguson Is the Wrong Tragedy to Wake America Up

Should Ferguson Protestors be Person of the Year? Vote below for #TIMEPOY

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com