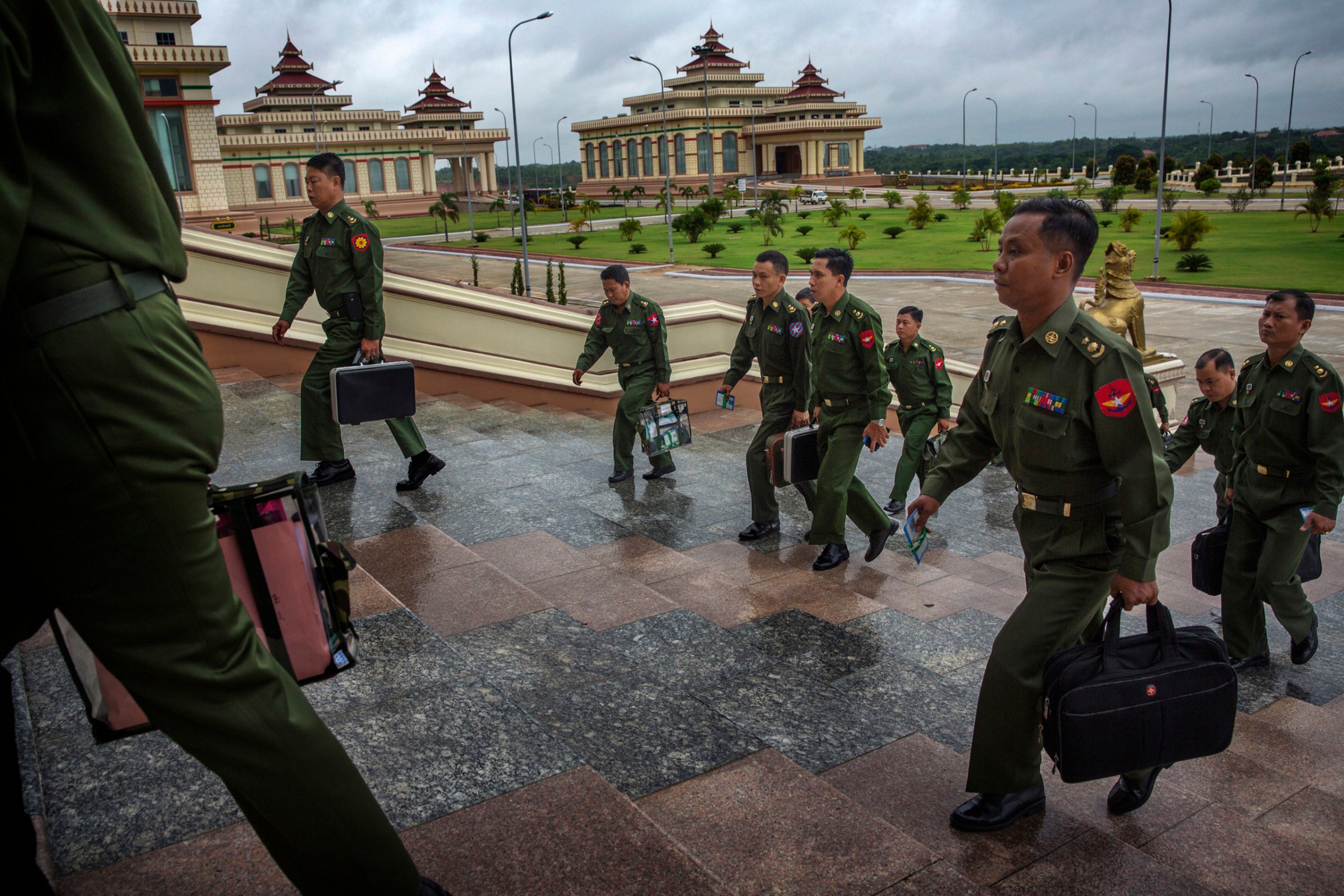

It’s one of the largest parliamentary complexes in the world, a legislature whose colossal size stands in inverse proportion to the actual work that occurs within its marbled halls. Each morning it’s in session, busloads of military brass, who are constitutionally guaranteed one-quarter of the 664 seats, roll up to the complex, its 31 spired buildings representing each plane of Buddhist existence. Then come vehicles filled with civilian MPs, the men outfitted in the jaunty headgear—silk, feathers, the occasional animal pelt—that is mandatory for male MPs not in the military. Among the last to arrive is a private sedan carrying Burma’s most famous lawmaker, democracy heroine Aung San Suu Kyi.

Suu Kyi, who won a 2012 by-election to represent an Irrawaddy delta township, cannot say much in the Assembly of the Union, the official name for the parliament. Nevertheless, she sits with her characteristic upright posture, intent on the proceedings; by contrast, the military members are sometimes caught snoozing.

From 1988 to 2011, the military junta that ruled Burma, known officially as Myanmar, saw no need for a legislature. But after the generals introduced a road map for a “discipline-flourishing democracy,” the new parliament was built from scrubland in Naypyidaw, the surreal capital that was unveiled in 2005, complete with empty 20-lane avenues and multiple golf courses. Across the city from the Assembly compound, another monstrosity looms, the Defense Services Museum, which sprawls over 244 hectares. It is located in the electoral district represented by Thura Shwe Mann, a battle-hardened ex-general who has refashioned himself as the influential Speaker of the lower house. Because Suu Kyi is constitutionally barred from becoming President in next year’s elections, Thura Shwe Mann could well succeed President Thein Sein—another general turned civilian leader—if Thein Sein follows through on promises to relinquish power.

For most of our museum visit, photographer Adam Dean, a Burmese friend and I are the only visitors peering at exhibits glorifying the Tatmadaw, as the armed forces are called, a 350,000-strong fighting force that has battled colonial oppressors and ethnic insurgents alike. As we enter each vast hall, a guide turns on the lights, then carefully extinguishes them as we exit. Electricity is expensive in Burma, and only after a group of cadets arrive on a school trip is the lakelike fountain in front of the museum allowed to unleash its jets of water. As we leave, the guide presses us for tips on the upkeep of the museum. “Any suggestions,” he asks, “for the quality of the lighting?”

Two Burmas

Since Suu Kyi was released from house arrest in 2010—the ruling generals locked up the Nobel Peace Prize laureate for 15 of the previous 21 years—Burma itself has been emerging from the dark. After nearly half a century of military rule, a quasi-civilian government has taken power, with army men trading their green uniforms for civilian dress. Suu Kyi and other members of her opposition National League for Democracy (NLD), which won the 1990 elections that the junta ignored, hold seats in parliament. In a world where democratic triumphs have become rare, Western leaders like U.S. President Barack Obama have lauded Thein Sein’s reforms and lifted some economic sanctions that had been placed on the military regime because of its atrocious human-rights record: forced labor, political imprisonment, institutionalized rape by Burmese soldiers, among other abuses. Newspapers compete with one another for the latest scoop in a country where press freedom was nonexistent a few years ago. Foreign investors looking to tap Burma’s bountiful natural resources have sent in scouts, and talismans of globalization like Coca-Cola are now available on local shelves.

But the caveats are many. For all the hype about a new frontier market, Western investors have remained cautious. In October a Burmese journalist who once served as Suu Kyi’s bodyguard died in military custody; his body showed signs of torture. Despite three years spent advertising an imminent national cease-fire, the Tatmadaw is still clashing with ethnic militias—like the Kachin, Shan and Ta’ang—who see little point in laying down their arms and submitting to a government dominated by a single ethnicity, the Bamar, or Burman. An extremist Buddhist movement has metastasized and is pushing for a law that discourages Buddhist women from marrying outside their faith. Violence against the Rohingya, a Muslim people living in western Burma, has been labeled “ethnic cleansing” by Human Rights Watch, the New York City–based watchdog, with hundreds killed and 140,000 sequestered in ghetto-like camps.

When Obama arrived in Burma earlier in November for a regional summit, he was far less ebullient than during his landmark visit two years before, noting that the nation’s reforms were by “no means complete or irreversible.” Shortly before Obama’s stop in Burma, the U.S. Treasury Department added Aung Thaung, a former hard-line junta member turned ruling-party lawmaker, to its blacklist for “intentionally undermining the positive political and economic transition in Burma.” American companies are now prohibited from dealing with Aung Thaung, whose family has interests in everything from timber to natural gas to banking.

The halo around Suu Kyi, the nation’s shining moral authority, has also dimmed. The transition from opposition symbol to government insider is always perilous. Not that Suu Kyi is President, of course. She is constrained by a clause in the military-authored constitution that disallows anyone with a foreign family member from becoming President—a rule that seems specifically designed for her. (Suu Kyi’s two sons, like her husband, who died of cancer when she was under house arrest, are British.) Despite international hopes and a nationwide campaign that collected nearly 5 million signatures, it’s unlikely that the constitution will be amended in Suu Kyi’s favor.

Even from her perch as parliamentarian, though, the 69-year-old daughter of Aung San, the founder of the modern Burmese army, holds the kind of global sway rivaled only by the Dalai Lama or Desmond Tutu. When she speaks, whether in her lofty Burmese or her crisp Oxbridge English, people listen. Yet Suu Kyi has kept largely quiet about the plight of Burma’s minorities, who together make up some 40% of the country’s 50 million-plus people. Her silence is particularly jarring when it comes to the 1 million-strong Rohingya. Suu Kyi now rarely meets with the foreign press—she declined an interview with Time—and avoids representatives from human-rights groups that spent years campaigning for her release. Some local activists are disenchanted. “Ever since independence, we Burmese have hoped for a hero to save us,” says Phyoe Phyoe Aung, a 26-year-old civil-society activist who spent more than three years in jail. “I don’t want to depend on one person, one leader, one Aung San Suu Kyi.”

If next year’s polls are free and fair, the NLD will likely prevail. But the party has done little to cultivate the next generation. Soe Moe Thu joined the NLD earlier this year and is now the new head of the party’s youth wing. He idolizes the woman known to Burmese simply as the Lady. “A leader like [Suu Kyi] is very rare anywhere in the world,” he says. “She is our icon.” Yet in his first three months as NLD youth chief, Soe Moe Thu sat down only once for a proper talk with Suu Kyi.

Ye Htut, Burma’s Information Minister, has perfected a line when it comes to the NLD. “If Suu Kyi is President, who will be the Vice President?” he asks during an hour-long conversation. “Who will be No. 2, No. 3, No. 4? Who are the other leaders in the NLD?” Ye Htut represents a government accused of backsliding on reforms—but he does have a point.

NLD lawmaker Win Htein endured 14 years of torture and imprisonment before his release in 2010. Somehow, he emerged from jail with his jollity intact—a fact he demonstrates sitting in his room at the Naypyidaw dormitory to which NLD lawmakers have been assigned, watching South Korean pop star Psy on TV. The 73-year-old cheerfully acts out “Gangnam Style,” swatting away mosquitoes with his cane. “Welcome to my palace,” he says with a wink. The rooms are oversize concrete cells, with each assigned little furniture beyond a hard bed and a desk. No Internet or air-conditioning is provided. Lawmakers pay packages equal to $660 a month. There’s just one NLD lawmaker who doesn’t live in these dingy barracks—Suu Kyi, the party leader, resides in a villa in a more glamorous part of Naypyidaw.

The Absence of Peace

Suu Kyi is scarce too in the sliver of Kachin state run by the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), which controls land near Burma’s northern border with China. The only evidence of the Lady is at a drug-rehab center. At night, 140 inmates are locked behind bars. They unroll thin sleeping mats and, in this Christian region, pray for strength and forgiveness. On the walls of one cell, a portrait of Suu Kyi has been sketched near a drawing of Jesus Christ—two saviors side by side. But Gam Ba, the head of the KIO’s drug-eradication effort, is dismissive. “The drug addict did not draw that because he likes her,” he says with certainty. “He did it because he was bored. The Kachin do not trust Aung San Suu Kyi. She is not fighting for us. She’s fighting for the Burmese.”

Suu Kyi’s father Aung San is credited with having formed an independent Burma by joining often feuding ethnicities into a federal state. But Aung San was assassinated before the nation gained independence in 1948 from the British. Since then, some of the world’s longest-running civil wars have festered in Burma’s fringes, where ethnic peoples live on land that is also the nation’s most resource-rich. Today there is little love displayed for Aung San’s daughter, a Bamar patrician, especially from those who practice faiths other than Burma’s dominant Buddhism. “For the NLD, amending the constitution so [Suu Kyi can be President] is a bigger priority than peace,” says Sai Hsam Phoon Hseng, an education and foreign-affairs officer for an ethnic Shan party. “But a big reason why this country is not developed is because of ethnic conflict. Peace should be the first priority.”

Since a cease-fire broke in 2011, after a 17-year pause in the fighting, more than 100,000 Kachin have been displaced, with little hope of returning to land now controlled by the Tatmadaw. Human-rights groups have documented rape and deliberate shelling of civilian settlements by the Burmese army. (Both sides have been accused of using child soldiers.) About 8,000 Kachin villagers now live at Je Yang refugee camp. As dusk falls, Maran Kaw and her family gather in their tiny room to watch a DVD. It’s a film of KIO propaganda, a disturbing depiction of sexual assault, execution and bloodletting by the Tatmadaw, complete with spurts of red paint and torn women’s clothes. “I will get nightmares from watching this,” she says, turning away, “because it reminds me of what happened in the villages.” But her grandchildren, ages 1 and 5, are riveted.

It’s a jarring scene, especially given the aura of peace that surrounds Suu Kyi, with her long-standing commitment to nonviolent resistance. But Burma remains a bloody place, and Suu Kyi’s critics accuse her of resorting to phrases like “rule of law” rather than condemning the continuing ethnic brutality. Beyond Kachin, she has disappointed on the fate of the Rohingya killed in pogroms in western Burma. The ethnic Rakhine, or Arakanese, who have clashed with the Rohingya, dismiss them as illegal immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh rather than recognizing them as an ethnicity with long roots in the region. Anti-Muslim sentiment simmers in Burma, as does resentment that the British brought people from the Indian subcontinent to work in their colony.

Suu Kyi has not fully acknowledged that the violence has disproportionately affected the Muslim Rohingya over the Buddhist Rakhine; she has also failed to speak out forcefully against a government plan to further disenfranchise the Rohingya, many of whom are stateless. “It is the duty of the government to make all our people feel secure,” Suu Kyi said earlier this month, when asked about the Rohingya, with Obama at her side. “It is the duty of our people to learn to live in harmony with one another.” The U.S. President was more direct: “Discrimination against the Rohingya or any other religious minority, I think, does not express the kind of country that Burma over the long term wants to be.”

There’s no question that in the Buddhist, Bamar heartland, Suu Kyi’s popularity endures. Utter her name and it’s like invoking a saint. But Burmese are also beginning to criticize her openly. Even in her constituency of Kawhmu, deep in the Irrawaddy delta where land speculation has driven up prices threefold in one month, there is a pushback. A self-styled real estate agent strides up, intent on selling a patch of rice paddy and banana trees for a ridiculous price in a community of wooden shacks and only occasional electricity. Mention that Suu Kyi had recently cautioned farmers against selling their land, and he shrugs. “Money is good,” he says. “She’s rich, anyway.”

She’s not, really. Suu Kyi lives in villas but she hardly surrounds herself in the gilded excess of Burma’s military elite and their cronies. The choices she faces are difficult. Once confined by house arrest, and a cloistered life of academia and motherhood before that, Suu Kyi may still be unaccustomed to the hurly-burly of politics. It’s easy to criticize her for failing to defend ethnic groups, but casual racism, particularly toward the Rohingya, is so ingrained in Burmese society that she would surely lose more supporters than she would gain by defending minority rights.

Still, the world is counting on Suu Kyi to use her moral suasion to fight prejudice, no matter the political consequences. But she may feel that the NLD needs to win an election before she can instill values in her people. In the meantime, others speak up for her. One unlikely defense comes from Wai Wai Nu, a young Rohingya activist who, like her entire family, spent time in jail. “Of course we are disappointed in Aung San Suu Kyi’s silence about us,” she says. “But we have no choice but to support her democratic party. What other hope do we have?”

Back to the Future

Close to midnight, the streets of downtown Rangoon are hushed, save for the scuffle of bare feet on cooling pavement. Young men are playing football on what during the day is a busy thoroughfare. Looming around them in this interfaith city, Burma’s biggest, are a Buddhist pagoda, a Baptist church and a Sunni mosque built by Indians who arrived during the British Raj. Around the corner from the football game is Sule Pagoda Road. It was on this avenue in 2007 that Buddhist monks upturned their begging bowls in a sign of defiance and marched for democracy. The columns of burgundy-robed holy men made for memorable images. So did the ensuing slaughter. Dozens, at least, were killed.

Today a billboard for a new mobile-service provider stands near the spot where a Japanese news photographer was gunned down by a Burmese soldier seven years ago. It’s a sign of Burma’s growing ties with the outside world. For all the frustration with Burma’s seeming regression, what was formerly one of the most closed countries in the world, run by a vicious military junta, has opened in ways that Burmese just a couple of years ago never could have dreamed. Suu Kyi, who remained a symbol of hope through those years of repression, deserves thanks for that.

How much has changed becomes clear when a man emerges from the dark. He is wearing a sarong and introduces himself as Mr. Toe. “Do you know what happened here a few years ago?” Mr. Toe asks in meticulous English. “Do you know who the Lady is?” A few years ago I would have taken him for an undercover agent, dispatched to lure sedition out of foreigners. Now it’s different. So we sit at a roadside stall, picking at tea-leaf salad and going over the army massacres of 1988, when even more civilians died, and the one nearly two decades later. He remembers the crowds of 2007, then the fierce syncopation of machine guns and the streets empty of everything but flip-flops orphaned by those who fled. “Oh my Buddha,” Mr. Toe exclaims, and we toast Suu Kyi with water, Coca-Cola and Burmese High Class whiskey. Burma’s dawn may still be far, but on this night, who can we honor but the Lady?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com