You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

McWATT’S VOICE (filtered, yelling):

Help him! Help him!

YOSSARIAN (into mike, yelling):

Help who?

McWATT’S VOICE (filtered, yelling):

Help the bombardier!

YOSSARIAN (into mike, yelling):

I’m the bombardier. I’m all right.

McWATT’S VOICE (filtered, yelling):

Then help him. Help him!

The chronicle of war is the Bible of irony. The original victim of that mistaken-identity crisis was a B-25 bombardier named Joseph Heller during a World War II raid over Avignon. He was a dozen feet from the pilot; yet they were separated by layers of chaos and terror. It was not Heller who was hurt—it was his gunner who was bleeding copiously into his flight suit. It was Heller’s 37th mission. From that instant of agony he grew petrified of flight. When his war ended, he took a ship home; it was some 15 years later before the flyer entered another plane.

The experience was too extravagant to be fiction and too real to be borne. Heller furnished the corpse with a vaudeville wardrobe, mixed in ’50s America, and called his novel Catch-22. Black, mad and surreal, it told of a bombardier named Yossarian impaled on the insanity of war and struggling to escape. Undergraduates still see Yossarian as a lionly coward, the first of the hell-no-we-won’t-go rebels who had to go anyway. To them, the book’s final sentence limns the human condition as well as the hero’s: “The knife came down, missing him by inches, and he took off.”

Catch-22 smacked of Restoration comedy. The characters trapped with Yossarian in the 256th Squadron had arch names: Major Major, General Dreedle, Colonel Korn, Milo Minderbinder. The contents seemed to be a series of hyperbolic World War II anecdotes, but its author confesses: “I wrote it during the Korean War and aimed it for the one after that.” The book was criticized as flatulent, self-indulgent and anachronistic—”Engine Charlie” Wilson’s General Motors, thinly disguised, was one of its archvillains. Moreover it followed Hilaire Belloc’s irritating dictum: “First I tell them what I am going to tell them; then I tell them; and then I tell them what I told them.”

Nearly 5,000,000 readers nevertheless found it one of the most original comic novels of their time. They found it so funny, in fact, that surely half of them ignored Heller’s own warnings: that Catch-22 is no more about the Army Air Corps than Kafka’s The Trial was about Prague; that “the cold war is what I was truly talking about, not the World War”; and that the second biggest character in the novel is death.

See Mike Nichols' Legendary Career in Photos

From Neurosis to Hysteria

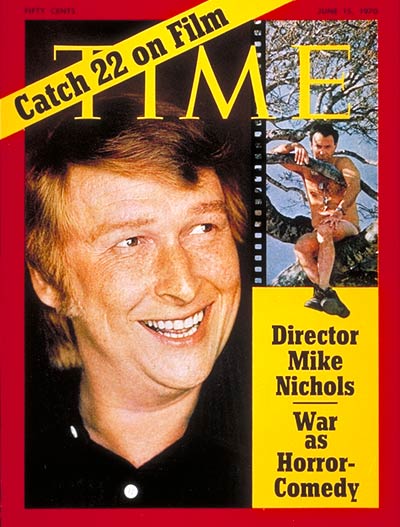

The biggest, of course, is Yossarian. Like most larger-than-death heroes, he is everyman. Still, some men are more Yossarian than others. Mike Nichols knows. And Alan Arkin knows. And Mike Nichols knows that Alan Arkin knows. “It was the only part I’ve ever worked on which didn’t demand a conception,” says Arkin, “because there isn’t much difference between me and Yossarian.” Viewing Arkin in the film of Catch-22 is like watching Lew Alcindor sink baskets or Bobby Fischer play chess. The man seems made for the role. Fear rides on his back like a schizoid chimp. His voice climbs from neurosis to hysteria—and winds back down again, without missing a moan. On Yossarian’s tortured face is a look of applied sanity that befits only saints and madmen. He walks through a closed system to which everyone but the dreamer has a key.

Arkin’s complex, triumphant performance is due in part to good genes —he looks more like Yossarian than he does like Arkin. In part it is due to a virtuoso player entering his richest period. But in the main it is due to the quirky talent of Director Mike Nichols, whose previous successes have been wrung largely from the bland and facile. It is as if Neil Simon were to turn out Endgame or Peter Sellers to turn into Falstaff.

The film is far from whole. Occasionally, it moves too slowly. Despite its determined timelessness, it suffers from inescapable time lag. The feudal state of the Army has the aspect of ancient history; bombing in World War II was like bombing in no other war before or since. When the novel was published in 1961, its nonviolent stance was courageous and almost lonely. But antiwar films have become faddish: lately, and Catch-22 runs the risk, philosophically, of falling into line behind M*A*S*H and How I Won the War.

Comedy, of all things, is the film’s weakest component. As an adapter, Buck Henry has supplied a terse, sufficient script; it is as a comic actor that he is wanting. In the part of Colonel Korn, he violates the first rule of humor: if what you’re doing is funny, you don’t have to be funny doing it. Playing outpatients of Dr. Strangelove, he and his Tweedledummy Colonel Cathcart (Martin Balsam) italicize every punch line. Even their faces are overstatements. As General Dreedle, Orson Welles sweeps past like Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, all plastic and gas. Dreedle need only have GREED lettered across his middle to complete the cartoon.

But Nichols was not making Super- M*A*S*H . From the beginning, he was aware that laughter in Catch-22 was, in the Freudian sense, a cry for help. It is the book’s cold rage that he has nurtured. In the jokes that matter, the film is as hard as a diamond, cold to the touch and brilliant to the eye. To Nichols, Catch-22 is “about dying”; to Arkin, it is “about selfishness”; to audiences, it will be a memorable horror comedy of war, with the accent on horror.

With psychiatric insight, Nichols has constructed Catch-22 like a spiral staircase set with mirrors. Yossarian ascends by dols, units of pain, glimpsing pieces of himself until he comes to a landing of understanding. It is 1944, Mussolini has collapsed, and Allied victory is inevitable. But for the bombardment group, there is no surcease. Colonel Cathcart compulsively keeps raising the number of missions required before an airman can be rotated Stateside.

Like a carnivore among vegetarians, Cathcart careers through the defenseless. The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) is chewed out for not writing inspirational sermons that will gain the unit a spread in the Saturday Evening Post. The flyers are ordered to raid civilian towns so that they can concentrate on producing nice tight bomb patterns in the aerial photographs. Most horrible of all, Lieut. Milo Minderbinder (Jon Voight) is encouraged in his murderous wartime profiteering.

Yossarian moves numbly through it all, reminiscent of the Steinberg drawing in which a rabbit peers out of a human face. He begs Doc Daneeka (Jack Gilford) to ground him as being insane with fear. But the flight surgeon dutifully recites the Air Force manual’s imaginary Catch No. 22: Naturally, anyone who wants to get out of combat isn’t really crazy. So supernaturally, anyone who says he is too crazy to keep flying is too sane to stop. On such circular reasoning rests the plot, the dialogue, and indeed the film’s essence.

Repulsive and Instructive

The dominant image is the circle. Catch-22 is as cyclic as the Soldier in White, a mummy-like form completely encased in bandages. At one end, a bottle feeds fluid into the region of some upper vein. At the other, a pipe conducts the fluid out of the kidney region and into another bottle. At a given signal, preoccupied nurses exchange the bottles, and the cycle begins anew.

Fully loaded, the bombers take flight, make their lethal gyres and return empty. Under Nichols’ direction, the camera makes air as palpable as blood. In one long-lensed indelible shot, the sluggish bodies of the B-25s rise impossibly close to one another, great vulnerable chunks of aluminum shaking as they fight for altitude. Could the war truly have been fought in those preposterous crates? It could; it was. And the unused faces of the flyers, Orr, Nately, Aardvark, could they ever have been so young? They were: they are. Catch-22‘s insights penetrate the elliptical dialogue to show that wars are too often a children’s crusade, fought by boys not old enough to vote or, sometimes, to think.

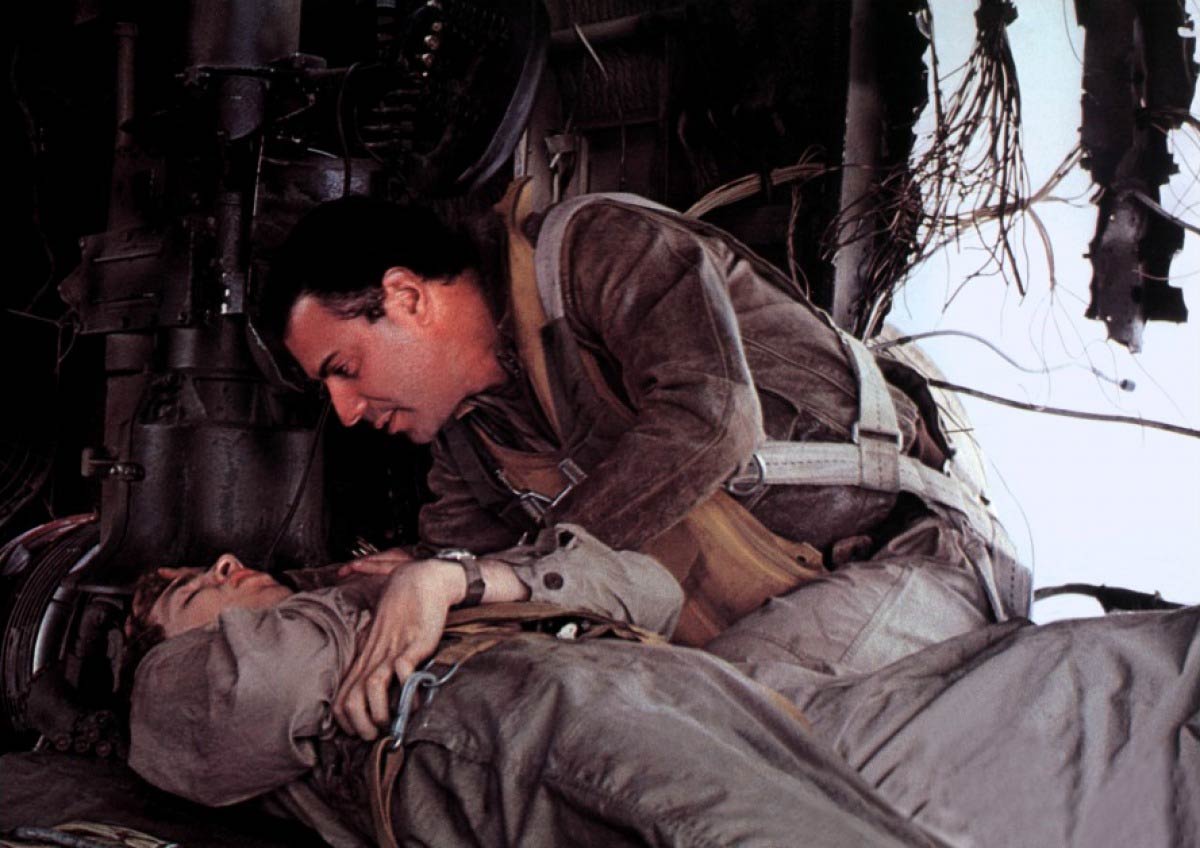

Yossarian’s mind circles five times to that instant in which McWatt calls out, “Help him!” Each time Yossarian’s arc of memory lengthens as he bends to aid the mortally wounded Snowden —until at last he sees the man’s flesh torn away and his insides pour out. It is at once the film’s most repulsive and instructive moment. From that time Yossarian cannot accept the escape bargain his superiors finally offer him: “All you have to do is like us.” He cannot betray his fellow victims of what Norman Mailer called “exquisite totalitarianism.” It is then that the rabbit must run or perish.

Most of the film has the quality of dislocation. It is lit like a Wyeth painting and informed with the lunatic logic of Magritte. Only twice does it grow didactic. In an Italian whorehouse, 19-year-old Nately (Art Garfunkel) confronts a 107-year-old pimp. The scene is photographed narrative, almost word-for-word from the book’s symbolic and simplistic confrontation: weary but supposedly immortal Italy v. vigorous but naive and supposedly doomed America. When the boy accuses the ancient of shameless opportunism, the centenarian defends himself with the ultimate weapon: age. “I’ll be 20 in January,” answers Nately. There is no answer to the old man’s Parthian shot: “If you live.”

As the film progresses, Lieut. Minderbinder descends from mess-hall hustler to full-time racketeer. In a crude and overdrawn caricature, the loutish blond fly-boy suddenly becomes a Hitlerian symbol who bombs American bases in a deal with the Germans and sells stocks in the war because it is good business. Here Nichols—like Heller—cannot let hell enough alone, and Engine Charlie’s oft-quoted G.M. dictum is paraphrased “What’s good enough for M-M Enterprises is good for the country.” But not for the movie.

Nichols had made his villains brobdingnagian. In lesser hands, the morality farce could have been substandard antiEstablishmentarianism: capital is evil; war is inhuman; people are groovy. There is something to be said for George C. Scott’s appraisal of Yossarian’s actions: “What the hell good does it do to take your clothes off, climb a tree and refuse to come down? What kind of rebellion is that?”

Waugh Parties in a Dirigible

Yet, because of the director’s persistent focus, it all makes the kind of perfect nonsense that finally is the concomitant of wisdom. Like Through the Looking Glass, Catch-22 overturns commonplaces and makes them fresh. Its optimism is despairing; its doubt is born of faith. “When Yossarian runs away in the end,” says Heller, “I never said that he would get all the way. I wrote: ‘The knife came down, missing him by inches, and he took off.’ But he tries, he changes. That’s the best that can be said for any of us.” It is the best that can be said of Nichols, who with this major film has discernibly altered not only his career but himself.

“Catch-22 has made me feel differently about what I lay on the line and what I do with my money too,” Nichols says. “There are suddenly so many urgent things that we must do for one another to make sure that we continue to live on this earth. The kind of après-moi-le-déluge parties and life-style that goes with them seem more and more distasteful. The accounts of such rounds are beginning to sound like Evelyn Waugh parties in a dirigible during a war.”

That general critique could be writ ten in the margin of Nichols’ auto biography. If he is indeed breaking camp, his move is Yossarianic in its scope. Nichols was the original enthusiast of urbane Waughfare. In the ’60s he compiled an unbroken string of Broadway smashes. He was a certified Beautiful Person, intimate of Lenny and Jackie, chum of Gloria Steinem, an original backer of Arthur, the slipped discotheque. Twice married, once divorced, once separated, he was the most eligible married male in Manhattan. His upper West Side triplex was decorated by Billy Baldwin. His Rolls waited obediently at the curb while he visited his fellow greats. His corporation was acquired by AVCO Embassy Pictures Corp. for $4,500,000. And yet, and yet, at that palmy time —was it only the day before yesterday? —there was a reason offered for Mike’s acidulous tongue and his lofty penthouse picture of society. It was the standard one, heavily merchandised by paperback Freudians: an unhappy childhood.

With Nichols, the reason was real. An émigré from Hitler Germany, Michael Igor Peschkowsky arrived in the U.S. in 1939. The seven-year-old could speak but two sentences in his new tongue: “I do not speak English” and “Please do not kiss me.” Forbearance is difficult for a little boy; there are people who will kiss a child no matter what he pleads. Mike learned how to offer a cheek and withdraw a psyche. He was a great sponge of a boy who decided to absorb the world.

One month after his arrival, Mike’s accent fell away like hand-me-down overalls. His father, a doctor, died when the boy was twelve. There was hardly any cash; the brilliant, aggressive student subsisted on scholarships and formed a lasting grudge against the unfeeling. To this day he remembers learning in terms of combat. “In grammar school you fight for your life and try not to get the crap beat out of you after school,” he recalls. “In high school you figure things are frozen forever in a certain pattern; there are a couple of guys you can beat up and a lot who can beat you up, and there are a few girls who’ll go out with you and some more that won’t, and that’s the way the rest of life will be. Then you get to college, and things seem to be a little more open.” A little, but not enough. Faced with this anatomy of melancholy, he opted for heavy anesthetic. He slept 16 and 18 hours a day.

Rinse Out, Please

In 1949, at the University of Chicago, like many another converted introvert, he woke up to performing. Wit is far more often a shield than a lance; ” Mike set up a complex of defenses that made him the fastest tongue in the Midwest. The second fastest was a hostile chick named Elaine May. It was love I at first fight. “Elaine held me like an autistic child,” Nichols remembers. The child bride he had taken at 19 was cast off. Elaine became a surrogate, although, says Mike, “it was much too serious for marriage.” And much too funny not to play it for audiences.

They began playing together in 1954, and by 1957 had improvised their way into national prominence as the mockingbirds of the American aviary. When they were around, no peacock, no eagle was secure. In their Broadway show, An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May, they did scenes in the style of O’Neill, and Batman, Proust, Pirandello and Noel Coward. Each swatch of material had a shiny button—as when Nichols, playing an English dentist, leans over his beloved patient: “I knew even then that I loved you. There, I’ve said it. I do love you. Let’s not talk about it for a moment. Rinse out, please.”

Their rise was based on more than matched metabolism and high literacy. Their stagecraft was impeccable. Elaine had been a child actress; before Nichols & May were joined with an ampersand, he had taken classes with Lee Strasberg. The guru of the Actors Studio had helped Mike along financially simply because he was overwhelmed by the kid’s “earnestness and directness.”

Saint Subber’s Stomach

Richard Burton remembers meeting Nichols and May backstage when he was starring in Camelot. “Elaine was too formidable . . . one of the most intelligent, beautiful and witty women I had ever met. I hoped I would never see her again.” Mike was less formidable, more agreeable. The mustard-colored eyes glinted, but the face had an unlined, almost feminine softness. The voice was as warm and resonant as a cello. Burton, who knows role playing when he sees it, was at first unconvinced by the proffered friendship and admiration. But eventually he enrolled Nichols in the Richard Burton fan club; it was an attachment that would one day pay off handsomely for Nichols.

Making up the act was a mutual idea; breaking it up in 1961 was Elaine’s. Closing the Broadway show, the comedians split amicably—only to rejoin when Elaine wrote A Matter of Position, a comedy starring Mike as a manic market researcher depressively afraid that people would hate him. They did. They also hated the play, which folded in Philadelphia after 17 performances. “It was not a pleasant experience,” admits Mike. “I behaved very badly toward Elaine.” She abandoned performing for about six years. Mike, as he says, “might have been Dick Cavett today” except for Saint Subber’s stomach. The producer owned a play by a TV comedy writer named Neil Simon. He remembered a funnyman who might just be able to direct. “Mike had misgivings and doubts,” Saint Subber recalls. “He said, ‘Why do you come to me?’ I said, ‘I chose you because I thought it out in my stomach. In the theater all you have are instincts.'”

Sharp Enough to Slice

Nichols remembers: “The first day of rehearsal, I knew, my God, this is it! It is as though you have one eye, and you’re on a road and all of a sudden your eye lights up, and you look down and you know, ‘I’m an engine!’ ” An engine that could. The play was called Barefoot in the Park.

What made it a smash hit, and far more than an expanded honeymooners skit, was the Nichols style: timing, vibrance and a slavish attention to detail. Nichols and failure became antonyms. Barefoot was followed by The Knack, Luv and The Odd Couple. The director came to resemble Somerset Maugham’s nouveau novelist, Alroy Kear, who read that genius was an infinite capacity for taking pains. “If that was all, he must have told himself, he could be a genius like the rest.”

Producer Alexander Cohen still remembers with awe when Nichols called him one night to rage: “This theater is in total darkness!” One of the 30 lamps on the balcony rail was flickering. Saint Subber’s marrow freezes when he remembers Nichols’ insistence that The Odd Couple set be repainted 24 hours before opening. When he cast Barefoot, Nichols was even more demanding. “Mike insisted on getting a real telephone man or a taxicab driver to play the telephone man,” recalls Subber. “I thought: this has to be a put-on. But I ended up getting a cab driver—and he is now an actor: Herb Edleman.”

Though audiences could no longer feel it, Nichols’ tongue was still sharp enough to slice. Richard Burton likes to retell the story of Walter Matthau, “a frenetic soul, and he finally blew his stack at Nichols’ Odd Couple direction. ‘You’re emasculating me,’ Walter cried. ‘Give me back my balls!’ From out front, Mike called back: ‘Props.’ ”

Mike was Burton’s kind of boy. As the Liz-Dick scandale deepened during the filming of Cleopatra, Burton recalls, “Ninety percent of our friends avoided our eyes. Mike flew to Rome from New York to be with us.” Nichols stayed by Elizabeth’s side when Burton went off to make another film. Favors like that one remembers. In 1966, the Welshman and his lady were signed for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and Elizabeth insisted on Nichols as director. Virginia Woolf could have been a mini-Cleopatra, but its be-low-the-belt punches intrigued critics and audiences. The second time out, with Dustin Hoffman and The Graduate, he won it all: money, the Oscar, and freedom for his third film, Catch-22.

By then, his manipulation of actors had become a patented amalgam of ad lib and calculation. “He makes you feel kind of like a kite,” says Hoffman. “He lets you go ahead, and you do your thing. And then when you’ve finished he pulls you in by the string. But at least you’ve had the enjoyment of the wind.” To Richard Burton, “He conspires with you to get the best from you.” Buck Henry’s appraisal is shrewder: “He tries to make you think that what he’s telling you is your own idea.”

Mike’s idea for Catch-22 began at Heller’s beginning, in Italy. Production Designer Richard Sylbert and Producer John Galley began hunting for Heller’s old base on the coast of Corsica. “We asked in our failing Italian, ‘Where is World War II?’ ” Sylbert says. Answer: nowhere. The base had been wiped out by highways and refineries. It was not until they flew over a mountain range dubbed “Goat’s Teats” near Guaymas, Mexico, that they found a place with what Sylbert called that “how-do-I-get-outta-here feeling.” Nichols took one look and flipped.

Do You Think Natalie Wood?

He had decided that the main design of the film should be as circular as the dialogue: holes in walls, arches, bombs. There were other circles involved. Catch-22 was a convergence of innumerable wheels. Jon Voight came to prominence playing opposite Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy, a job Hoffman would not have landed had he not been in Nichols’ The Graduate, an assignment Hoffman won because of his excellence in the play Eh? directed by Arkin. After playing Yossarian, Arkin was to direct Little Murders, by Jules Feiffer, who has written Nichols’ next project, Carnal Knowledge.

To onlookers, journalists and occasional tourists, the interrelationships on the set seemed to be a piece-by-piece reassemblage of a New York cocktail party in the Mexican boondocks. Nichols played chess, anagrams and his famous-name games: “What did Gary Grant? Do you think Natalie Wood?” There were sexual boffs: When Nichols wanted to record a special sound from Nurse Duckett, he had Arkin grab Paula Prentiss’ thigh. Nichols, unnoticed, stood behind her and lunged for her breasts. “Mike was very happy with my hoot,” says Prentiss. “Then I was so overcome I had to go into a corner and be let alone. Whenever someone touches me I’m in love with him for about eight hours.”

John Wayne came down, got snubbed and drunk. Nichols danced down an airplane runway with Candice Bergen, who had come to take pictures and write an article. Bob Newhart, the paranoid Major Major, replayed his stand-up routines. Perkins restaged his staircase scene from Psycho. And underneath, it was one of the tensest, most grueling areas since Anzio beach.

“Mike has a funny blind eye when he works,” says Buck Henry. “He thinks everybody is always having a grand time. Everything may look rosy with a group of actors playing dirty-word games in the shade, but inside the command post the subtext is going on: an actor is on the verge of being fired; the lighting director isn’t speaking to the director; someone’s trying to negotiate with Orson Welles in Spain from the only phone on the base, which went through three Mexican cities on party lines.”

Nichols decided that Stacy Keach, cast as Cathcart, was “too young and light for the part.” The actor was spirited away at dawn. Keach, who distrusted the parochial atmosphere, now identifies Nichols with the psychotically ambitious Cathcart. “Psychologically,” he says, “I saw him in that position. In fact, I think he should have played the role.”

Taking My Life Tonight

Orson Welles arrived and began his lecture series: to Nichols on direction, to Film Editor Sam O’Steen on cutting, to actors on acting. But he consistently blew his lines and ended by being led through his readings by Nichols. When a B-25 roared over the compound and 18,000 sticks of dynamite ripped into buildings, huts and shacks, an actor forgot his lines. It was at times like this that Nichols would whisper to Buck Henry not quite facetiously: “You carry on; I’m taking my life tonight.” The costs kept rising. The end result totaled some $15 million—much of it invisible onscreen. It will have to gross $37.5 million before it turns a profit.

Even beyond Mexico, there remained a residue of despair. After four months of shooting in Guaymas, two months in Rome and a month in Los Angeles. Nichols confessed that he was “pregnant with a dead child.” In everything he had previously accomplished, there had been an accretion of finicky brush strokes that became a character or a landscape. With Catch-22, there was a stripping away. He pared easy gags from the script. He erased nearly 300 extras because the picture “was beginning to look like Twelve O’Clock High.” Sylbert was instructed to strip the sets bare; a whorehouse became a room, a bed a radiator. On the set, characters were dropped. In the cutting room, during eight months of editing, speeches were shaved. There was no musical score.

One afternoon, after three months in the dark, cluttered editing room, Nichols called to Galley: “Hey! I want you to come and look. I think I love it.”

In its finished form, the movie contains several stylistic allusions to other film makers. Catch-22‘s degenerate Roman tour is frankly Fellini. The airborne scenes have obvious overtones of Kubrick—indeed, Nichols bowed to his film-making friend by repeating a brief and thunderous musical theme from 2001. Catch‘s galvanic jumps in time owe much to Richard Lester. Still, the film has the force of a source—the kind of work that other film makers will soon be quoting.

To a degree, the film’s premonitory quality is a result of externals. Says Henry: “Heller was writing about a man who finally decided to opt out and who, in the end, ends up in Sweden. That was a total absurdity when he wrote it in 1961, a really far-out kind of insanity. Well, it’s come true.”

Not literally — the fictional fugitive of 1944 had paid his dues; it is too facile to see him merely as a Viet Nam drop out 25 years before his time. Galley regards the film as an extension of the 7 o’clock news: “Unfortunately,” he says, “it seems that you can al ways count on the country to do things to keep a picture like this timely.” Heller himself says, “When I saw the film I expected to be disappointed — after all, I had no part of it. But I saw what Mike had done. He didn’t try to make it just an antiwar movie or an insane comedy. He caught its essence. He understood.”

And All Ours

Apparently it is not all he understood. “You can’t increase the size of your nature,” Nichols says. “But you can be true to it.” Gazing at the rear-view mirror, he confesses that a second look at Virginia Woolf “bored me. I hate the way it’s photographed.” The Graduate? “My eyes pass it as I look. It’s like a blank place in my head.”

As for the stage work back in the Broadway days, the harshest judgments come from a friend, Buck Henry, and an enemy, Scenarist William Goldman. Says Henry: “Mike is one of the most famous directors in the U.S., but he hasn’t made one significant contribution to the theater. I think it’s a fanatical waste of time, but he’s crazy not to do Pinter. He should have done Joe Orton’s farces. But Mike doesn’t want to do any thing badly. He takes a risk, but he takes a risk on things he knows he can do better than anyone else.”

In his carping book The Season, Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) devoted a whole chapter to Nichols sardonically entitled “Culture Hero.” Wrote Goldman: “Nichols’ work is frivolous — charming, light and titanically inconsequential . . . What Nichols is is brilliant. Brilliant and trivial and self-serving and frigid. And all ours.”

Let’s Begin

Until Catch-22, Nichols’ demur would have been as hollow as his hits. Abruptly, he has supplied his own defense. The film, he claims, perhaps too extravagantly, has “helped me discover how I want to live—I’m going to get rid of myself in stages.” In any case the film has apparently made him demand more of himself professionally. Says Nichols, “It’s come clear that you have to make your own statement. I’m well aware of the separation between what you say and do. But it has to be begun, so all I’m really saying is, ‘Let’s begin.’ ”

The speech has the ring of a World War II bombardier who has chosen a difficult—and perhaps impossible—way home. Will anyone call the way trivial and self-serving and frigid? If so, the only reply can be: “The knife came down, missing him by inches, and he took off.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com