For her latest photo book, American photographer Carolyn Drake traveled to China’s far western province with a box of prints, a pair of scissors, glue, pencils and a sketchbook and asked her subjects to draw on, reassemble and play with her photographs in the hope that their creations would foster a different kind of dialogue. For TIME LightBox, she explains her process.

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is a remote place, 2,000 miles from Beijing. It is China’s far-western province. Like many first-time visitors, I was immediately confounded when I arrived in 2007. There were farms growing out of the desert, city streets that twisted and turned like mazes, and the people were loud, friendly, and seemed to be living their private lives publicly, on the streets and with open doors. I was based in Istanbul at the time, but ended up going back to Xinjiang many times over the next seven years, staying in Uyghur villages and cities on the edge of the Taklamakan desert.

Over these visits, the surfaces I was initially drawn to filled with stories. A man who made Islamic prayer socks for a living told me about his first love, who he still longs for after 20 years apart; about how she betrayed him that night at the bar while he was playing music. An art professor described his recurring nightmare of getting fired from his government job, and joked about his kids talking to him in Mandarin Chinese instead of their first language, Uyghur. A blacksmith arranged secret rendezvous for our meetings because he didn’t want his neighbors to know he spoke English. There were dowries arranged, brides given away, first sons born, extramarital affairs. When I decided to wear a headscarf and eat halal, a family took me in because I was interested in Islam, then closed me out, deciding that I wasn’t.

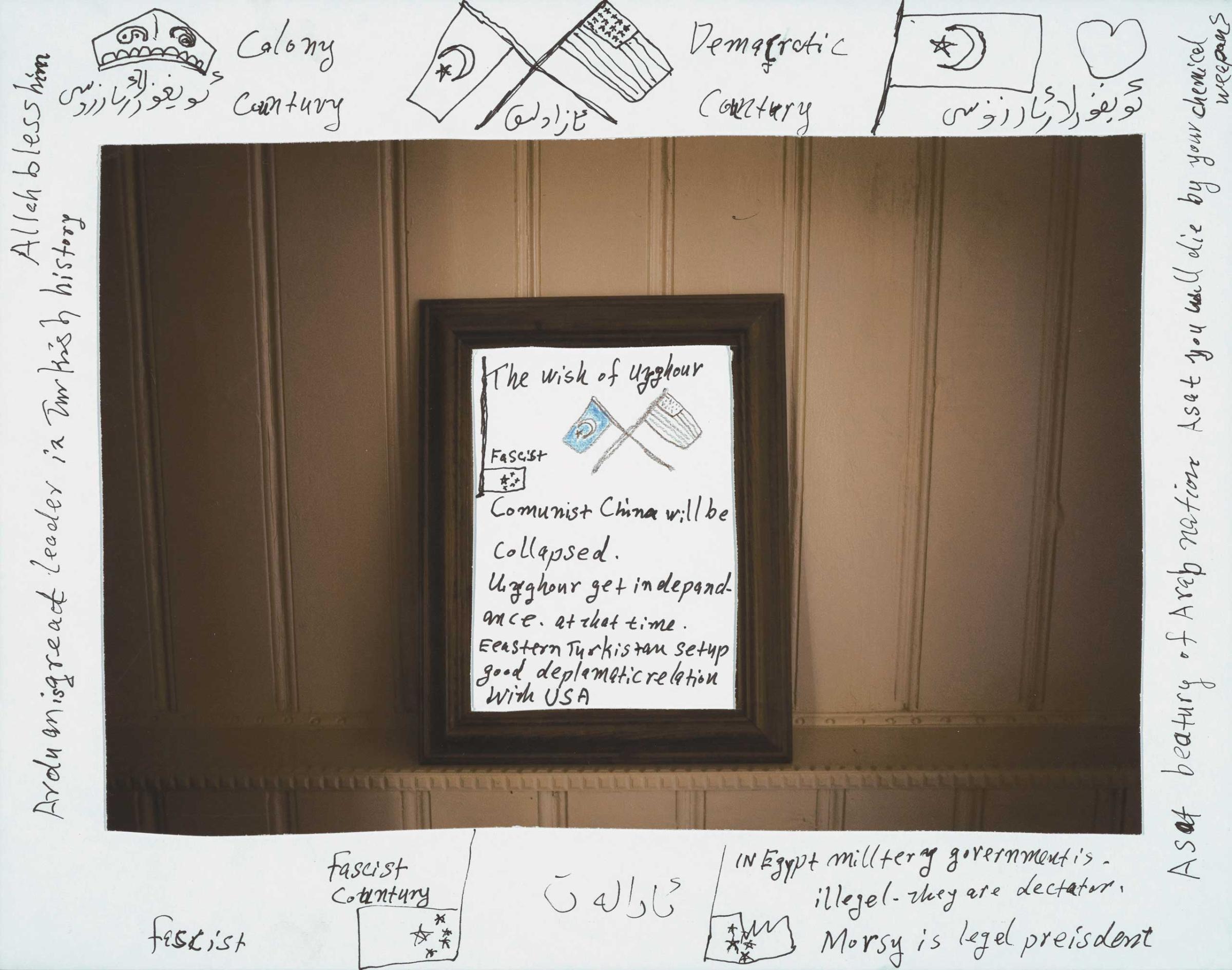

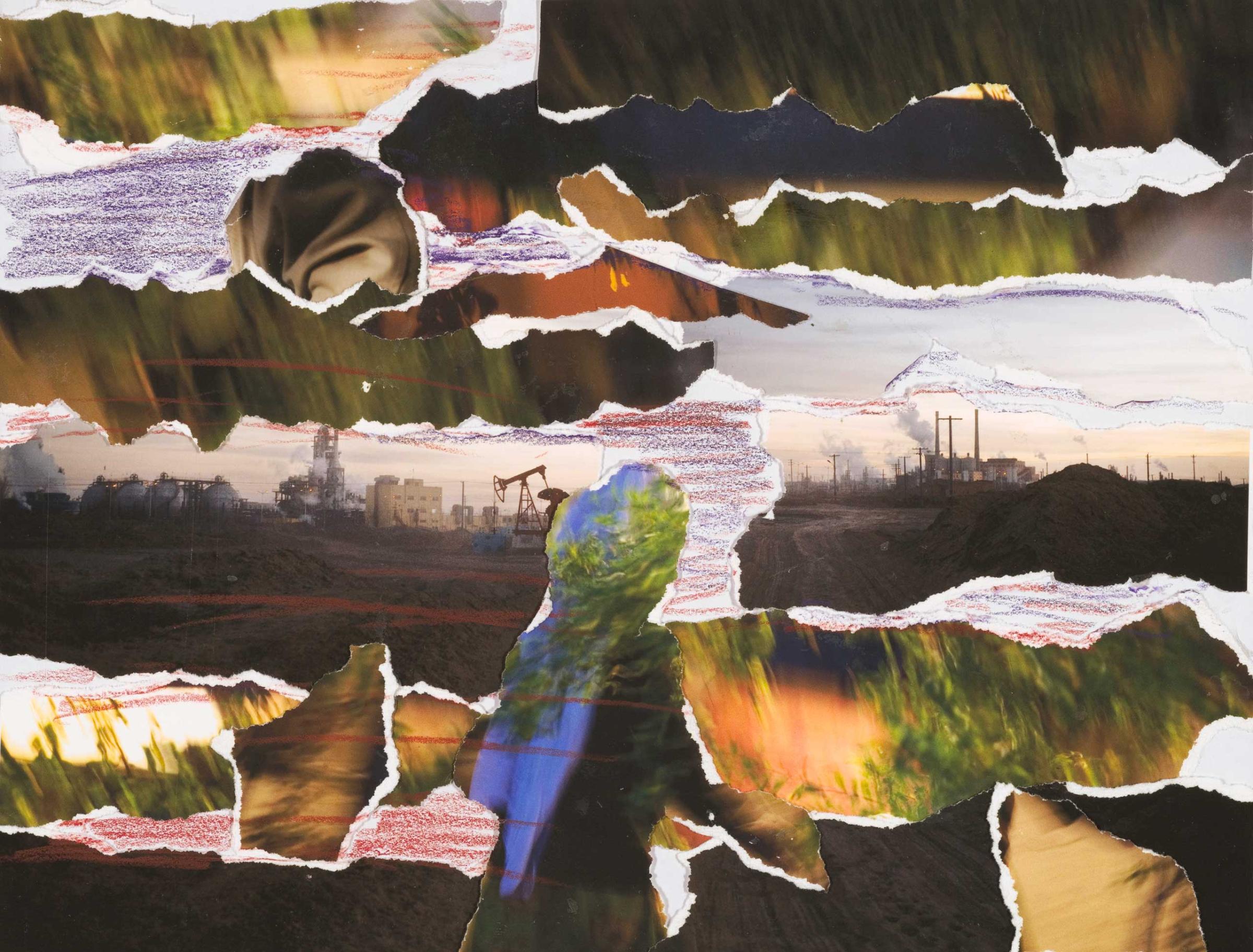

The landscapes changed as quickly as the stories filled them. Historic Uyghur neighborhoods were being torn down and rebuilt as modern Chinese cities, a result of government development policy. Uyghurs moved from houses with courtyards into apartments, and more and more Han Chinese filled the streets. In 2009, there were riots in the capital of the province, Urumqi, and many people died. Uyghurs were not permitted to speak with the press, but a man on the street furtively slipped me a piece of paper explaining in his own words what was happening. Back home, I received Google alerts every week combining flowery descriptions of a fading culture with news reports of violent incidents pitting “restive” Uyghurs against Han Chinese.

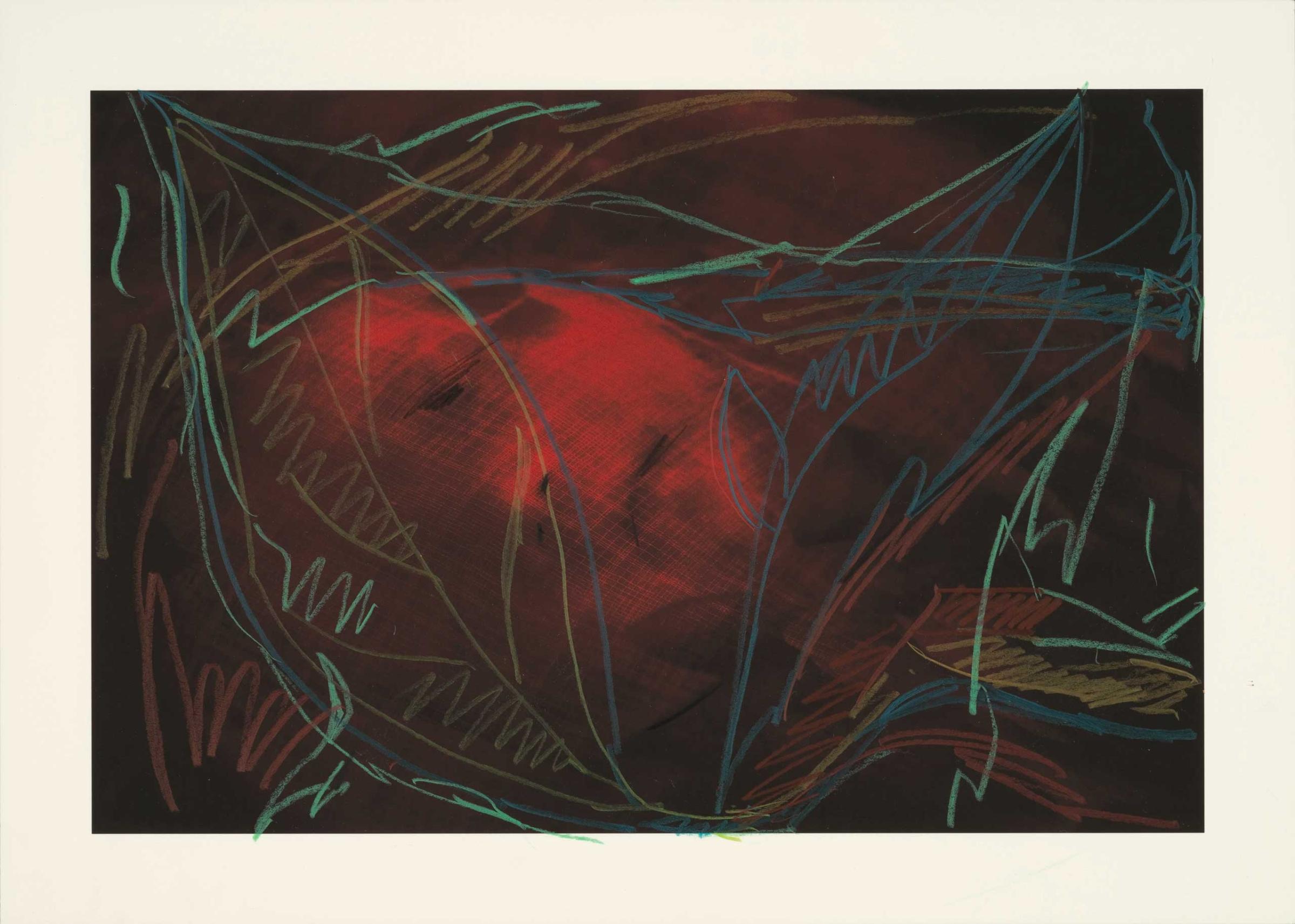

Through all this, I made pictures, but the political climate had placed a barricade between me and the people I was trying to connect with, and it began to seem impenetrable. Uyghurs who carry on extended conversations with foreigners risk police interrogation, and foreign journalists are routinely followed and thwarted. Meanwhile, some Uyghurs are opposed to artwork (including photography) depicting living creatures, since only Allah has the power to give life. I began to wonder whether photographs taken from my viewpoint alone could adequately represent the Uyghur experience. And what, if anything, did the pictures I was taking mean to the people in them? To what extent could we really understand each other anyway, given differences in language, faith, and experience?

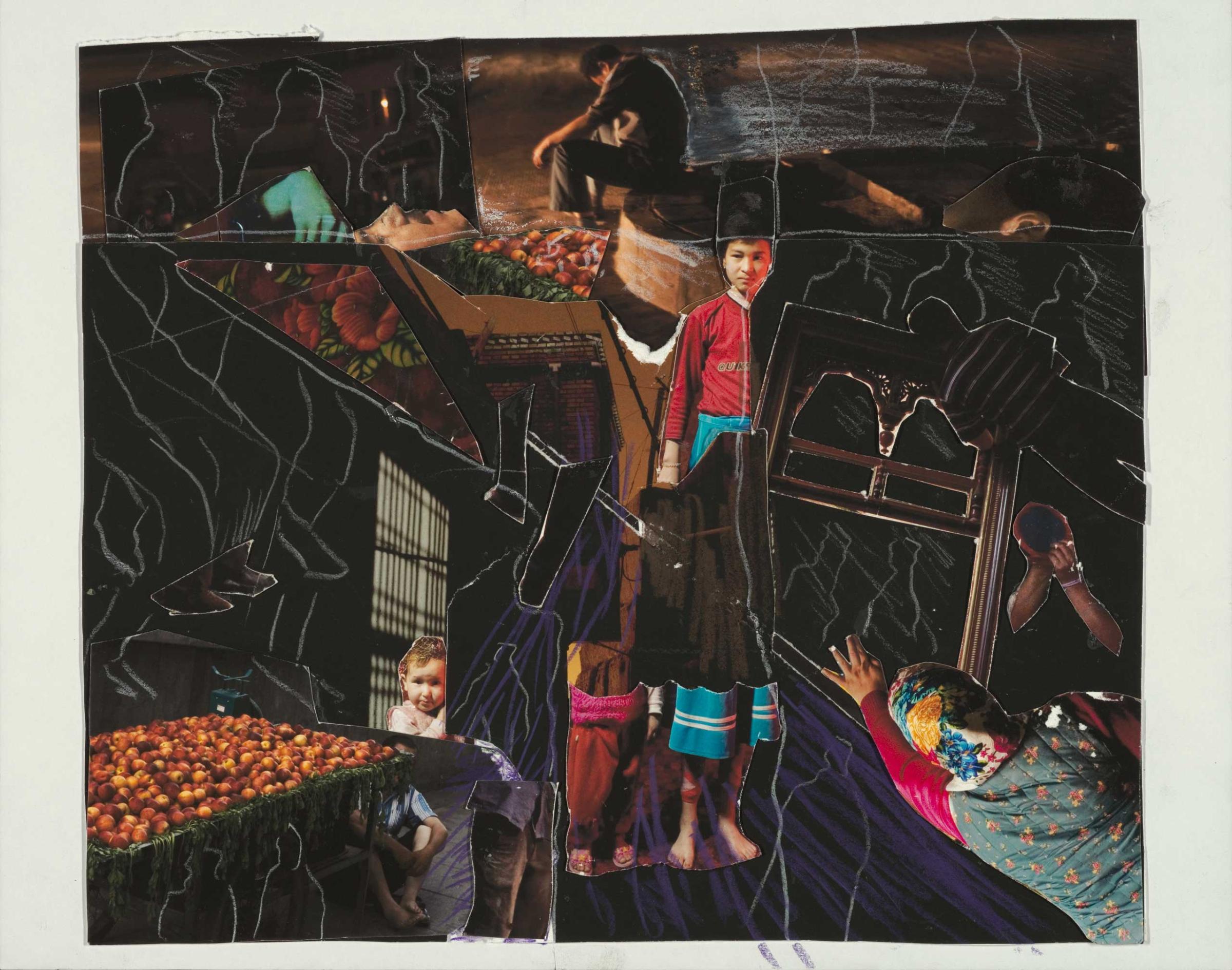

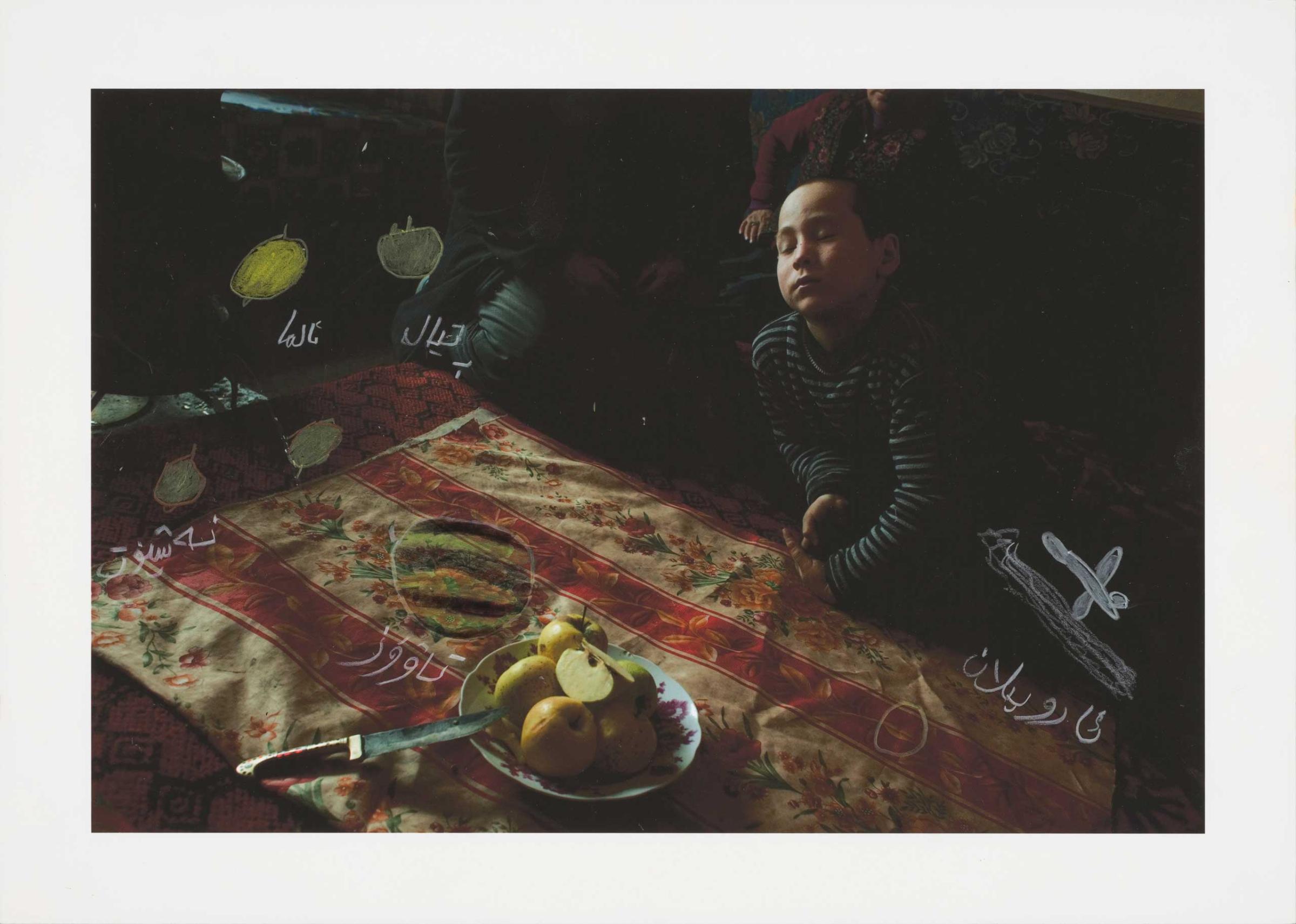

I decided to stop taking so many pictures, start looking for meaning at the intersection of our views, and find ways to bring the people I was meeting into the creative process.

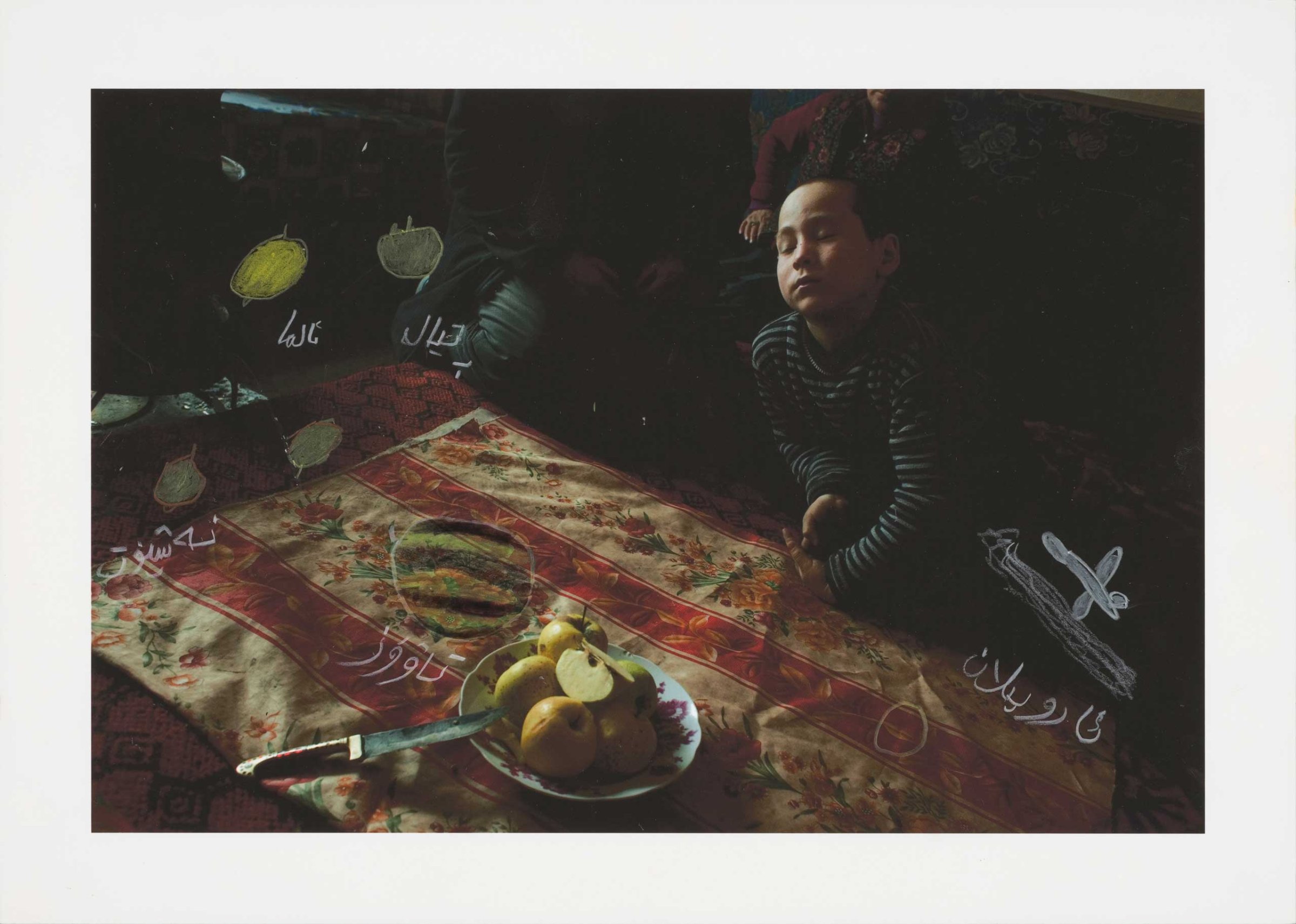

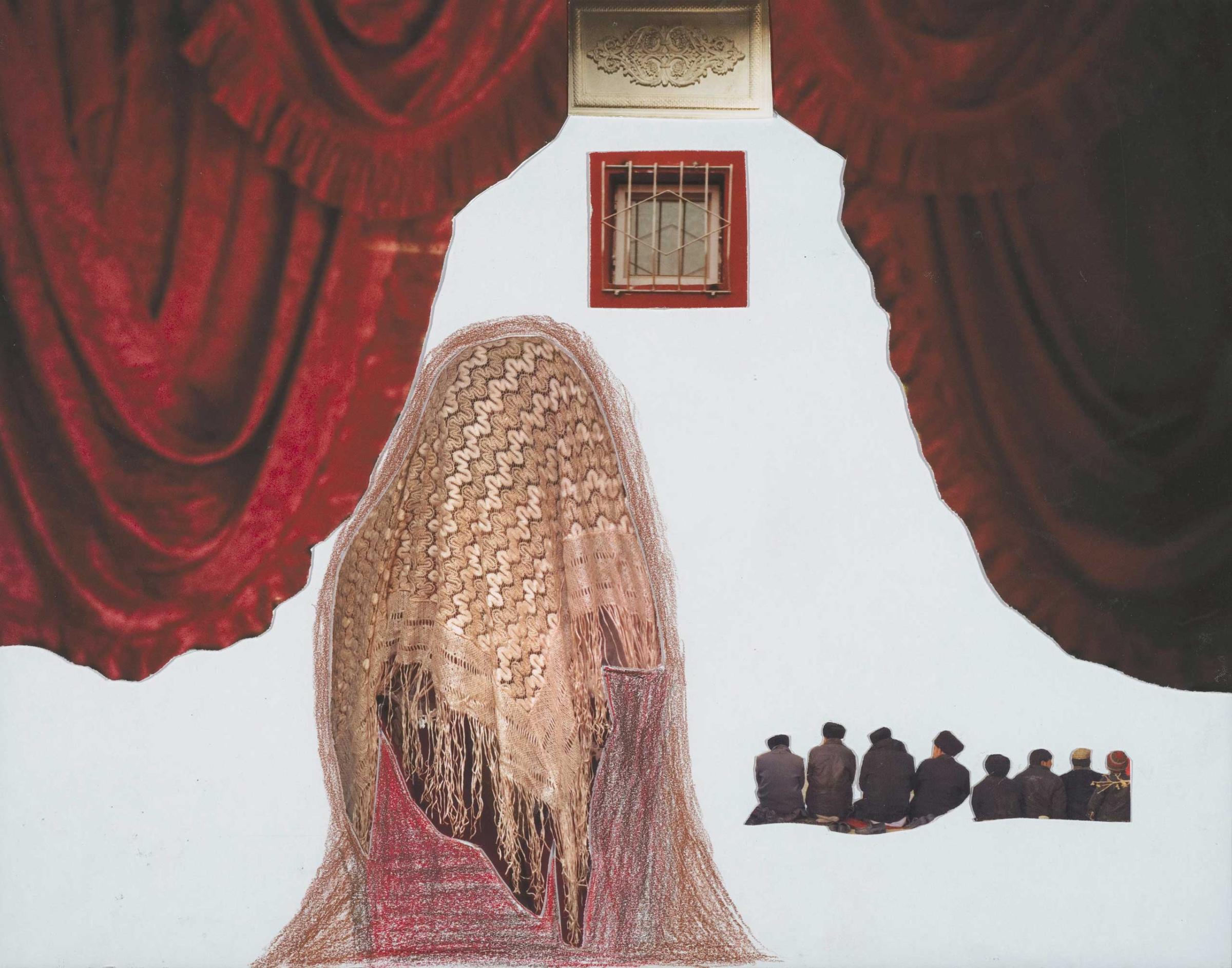

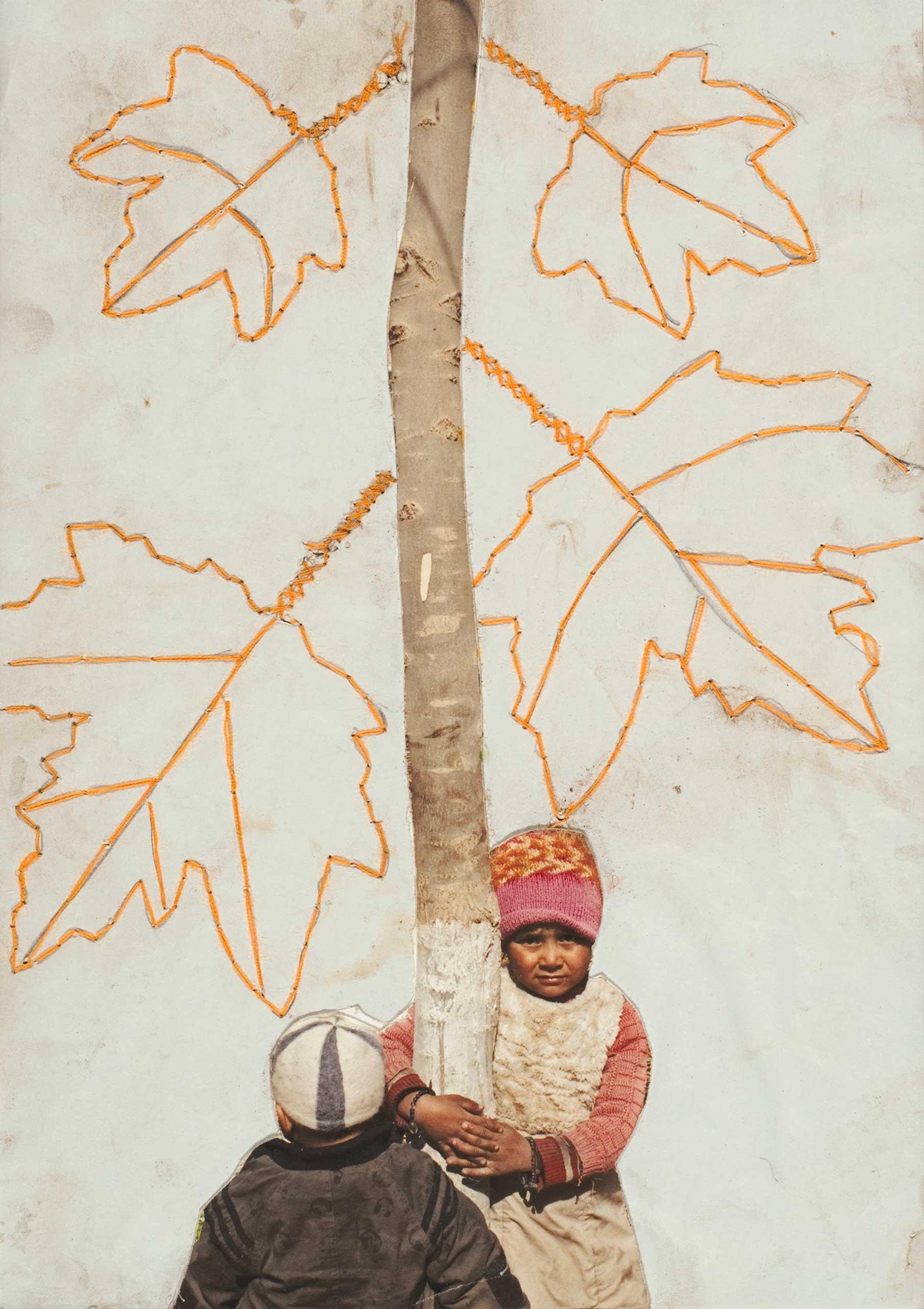

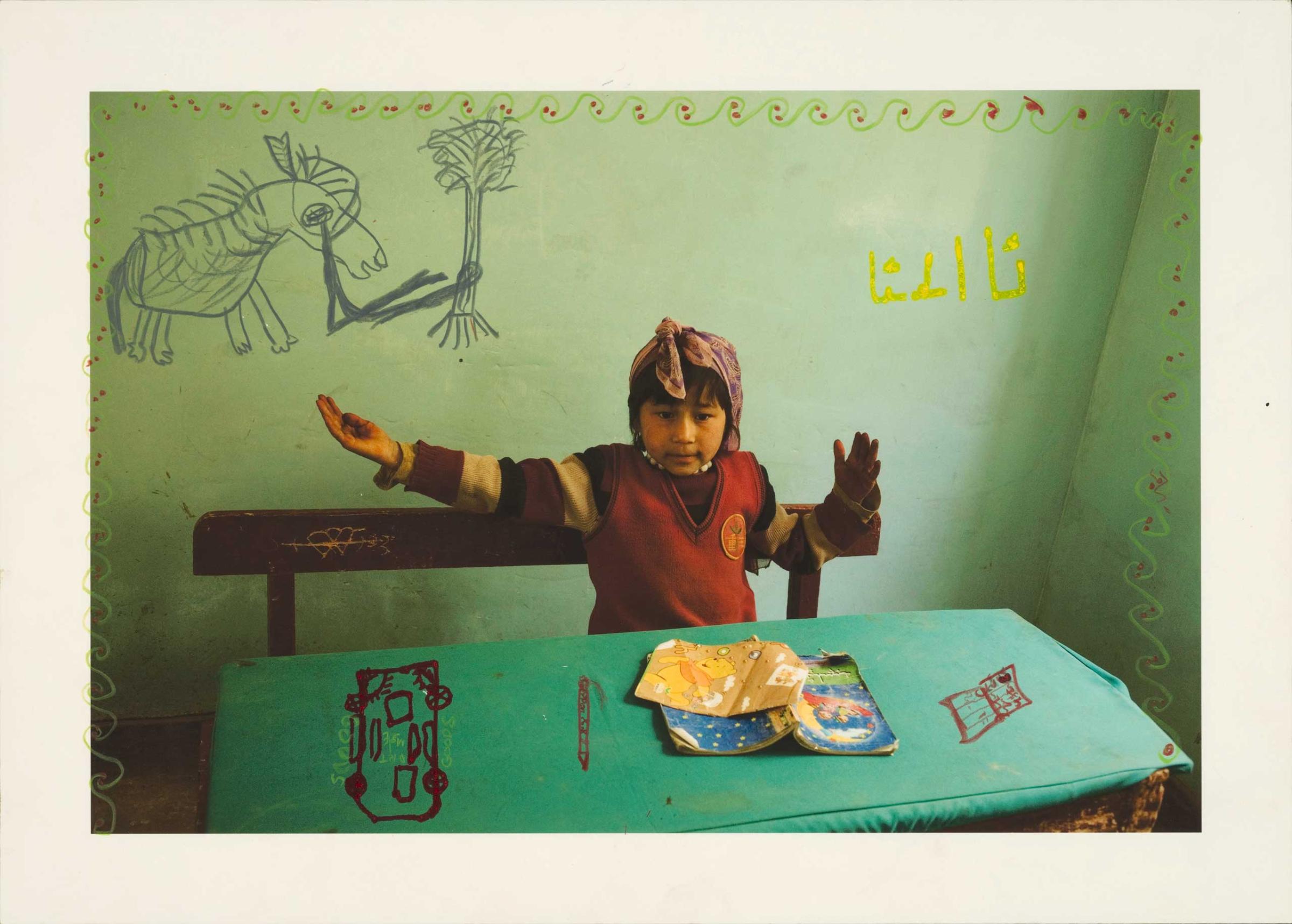

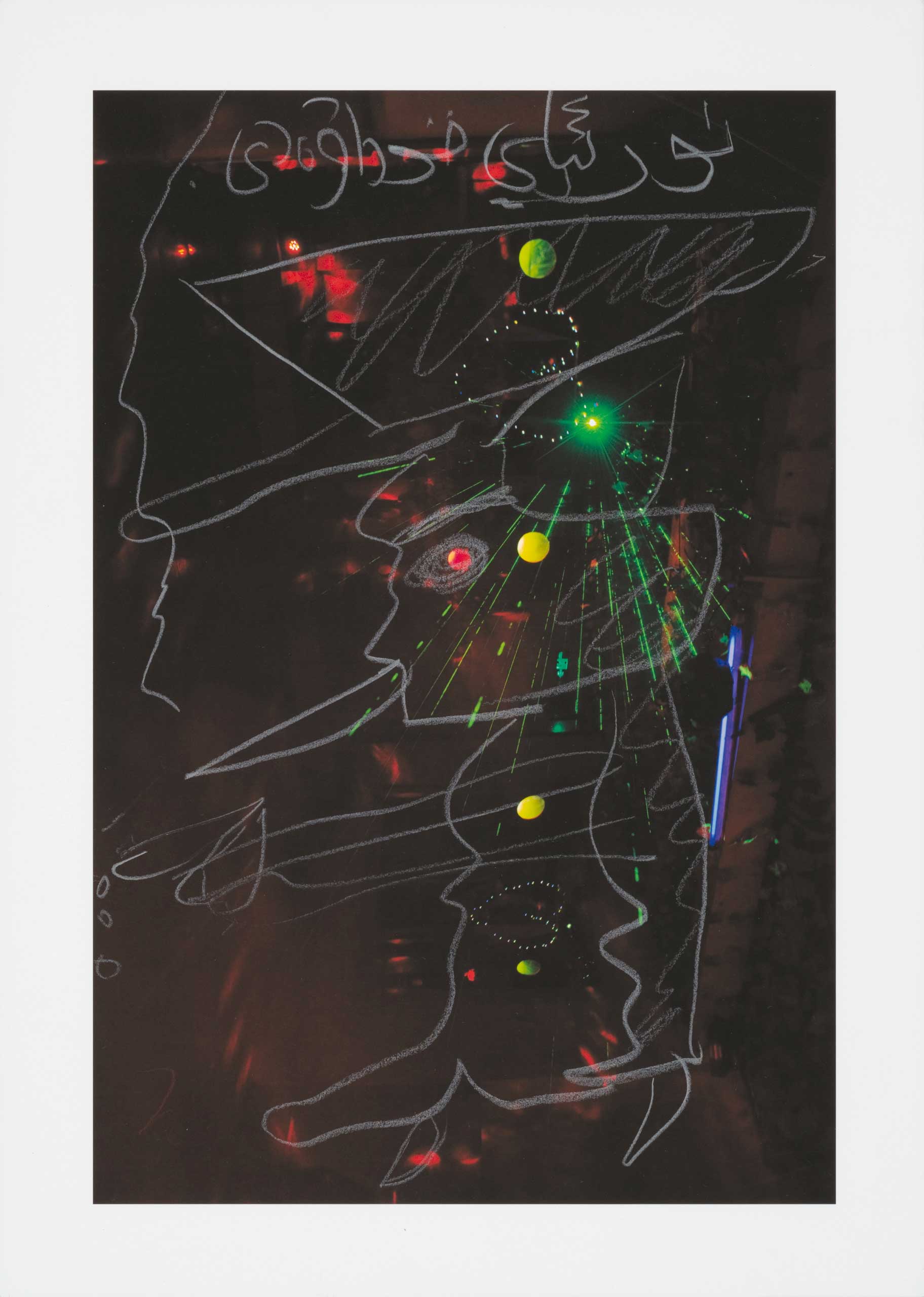

Traveling with a box of prints, a pair of scissors, a container of glue, colored pencils, and a sketchbook, I asked willing collaborators to draw on, reassemble, and use their own tools on my photographs. I hoped that the new images would bring Uyghur perspectives into the work and facilitate a new kind of dialogue with the people I met – one that was face-to-face and tactile, if mostly without words. We sat down together in restaurants, art studios, shoe shops, walnut orchards, public parks, courtyards, hotel rooms, slaughterhouses, and jade bazaars while they worked on the images. The collages and drawings they made are the product of our exchange, in all their roughness, ambiguity, and risk.

Looking for inspiration in Uyghur approaches to storytelling, I also started collecting Uyghur literature, music, and poetry. Among the many works that stood out was Wild Pigeon, a short story by Nurmuhemmet Yasin, an author of essays and poetry and stories in the Uyghur language.

An allegory of the Uyghur experience, Wild Pigeon circulated widely after its publication in the Kashgar Literature Journal in 2004, but it was met with disapproval by Chinese authorities. Yasin was arrested and sentenced to ten years in prison for “inciting separatism.” His prison term officially comes to a close this year, but inquiries about the status of his sentence remain unanswered, and it is unknown if he is still alive. Yasin is one among many who have been imprisoned under this charge. Just before this book went to print, Ilham Tohti, a Uyghur economics professor who has criticized the exclusion of Uyghurs from economic benefits offered to Han Chinese migrants in Xinjiang, was sentenced to life in prison, accused of separatism.

The grandfather whose interview is printed on the outside of this book told me I should visit graveyards if I wanted to learn about Uyghur culture. He has since passed away, but his nephew, who I know well, pays his respects to the deceased every Thursday in the sandy field across from his home where his relatives are buried. In his downtime, as he has for many years, he continues shuffling paperwork, stamps, and fees, hoping to obtain a passport to travel abroad. He wants to learn about what’s happening in other parts of the world beyond China. Despite the numerous obstacles, he trusts and believes he will eventually get there.

Wild Pigeon by Carolyn Drake is available now and will be on show at the Paris Photo art fair in France until Nov. 17, 2014.

Phil Bicker, who edited this photo essay, is a Senior Photo Editor at TIME

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com