When does a public university system become one in name only? That’s the question facing California as officials in charge of the state’s prestigious, but financially-struggling university system clash over how to keep it afloat.

On Nov. 20, the regents that control the University of California system will vote on a proposal to increase tuition at its 10 campuses by as much as 5% a year for the next five years. This year’s tuition and fees for in-state students is $12,192, which could rise to $15,564 by the 2019-20 school year under the proposal. The plan was conceived and put forward by Janet Napolitano, who took over the UC system in 2013.

The fight over the tuition increase pits Napolitano, the former governor of Arizona and federal homeland security chief, against Governor Jerry Brown, a popular figure in the state who was just re-elected with a sizable mandate. Brown has said he opposes increasing tuition, and would restore some state funding cut during the recession only if it stays flat. Brown is a regent and is among a handful of those on the board who have already indicated they will reject Napolitano’s proposal.

“There is a game of chicken,” says Hans Johnson, a higher education expert at the non-partisan Public Policy Institute of California. “It’s not clear to me at all how it’s going to turn out.”

Underlying the clash of big personalities is a philosophical debate about the changing funding models for public universities. In 1960, California created a lofty master plan that said higher education should be free or very low-cost for residents. “We’ve moved away from that pretty dramatically,” says Johnson. “It’s almost traumatic for California to think about it.” In recent decades, the state has decreased the share of overall public higher education costs it pays for and the system has become increasingly dependent on student contributions, among other sources, for the difference. In the 2001-02 academic year, in-state tuition and fees for UC campuses was $3,429, about one-third of the cost today. Similar trends have played out in state university systems elsewhere as well.

The recession accelerated public schools’ reliance on private money. At UC, the system receives some $460 million less per year in state funds than it did in the 2007-08 school year.

“As a political matter, state officials have made the judgment they don’t want to pay for higher education for our citizens,” says David Plank, an economist at Policy Analysis for California Education, a non-partisan research center. “What were once public universities are now private universities that receive some subsidy from the states.”

Napolitano says that if UC is to remain a world-class educational and research institution, it needs more money, no matter the source. And she says students and families will need to fill the gap left by the state. The proposed tuition increase would affect only around half of the student body. Thanks to income-based federal and state grants, about 55% of UC students pay no tuition.

Gavin Newsom, California’s lieutenant governor, has said he and Brown were blind-sided by the tuition increase proposal. The governor’s office has said Napolitano’s plan could void a plan Brown has endorsed to increase state funding 4 percent per year if tuition stays flat. Napolitano has said she never made a deal and if was one was struck before she took charge, she hasn’t found any record of it. “It was unilateral. It wasn’t anything we agreed to,” says Steve Montiel, a spokesman for Napolitano.

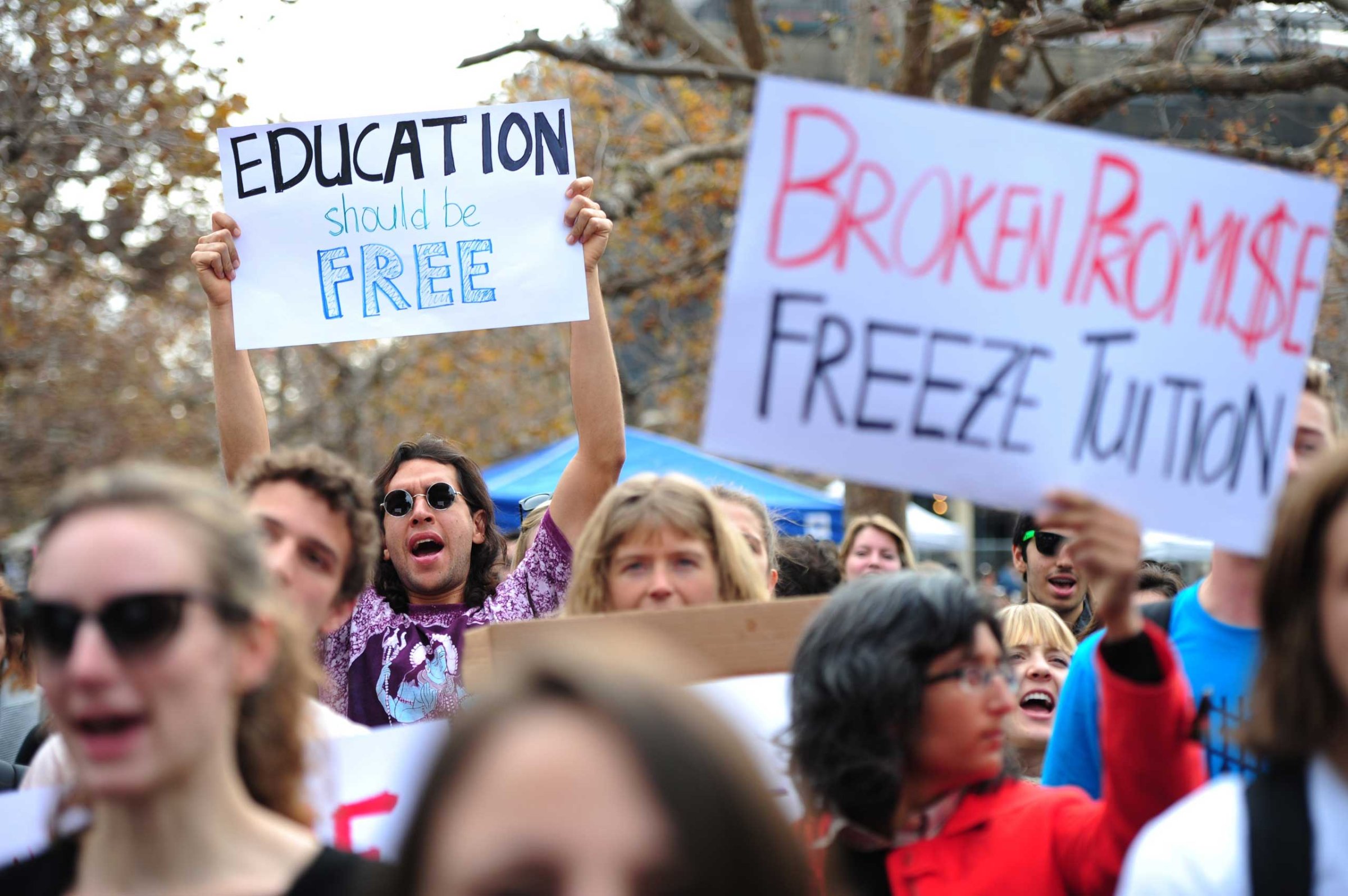

On the eve of today’s meeting of the regents planning board, the speaker of the California state assembly reportedly proposed directing $50 million in additional state general funds to UC to stave off increased costs for students. The proposal followed student protests at at least two UC campuses this week.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com