Correction appended, Nov. 18, 2014

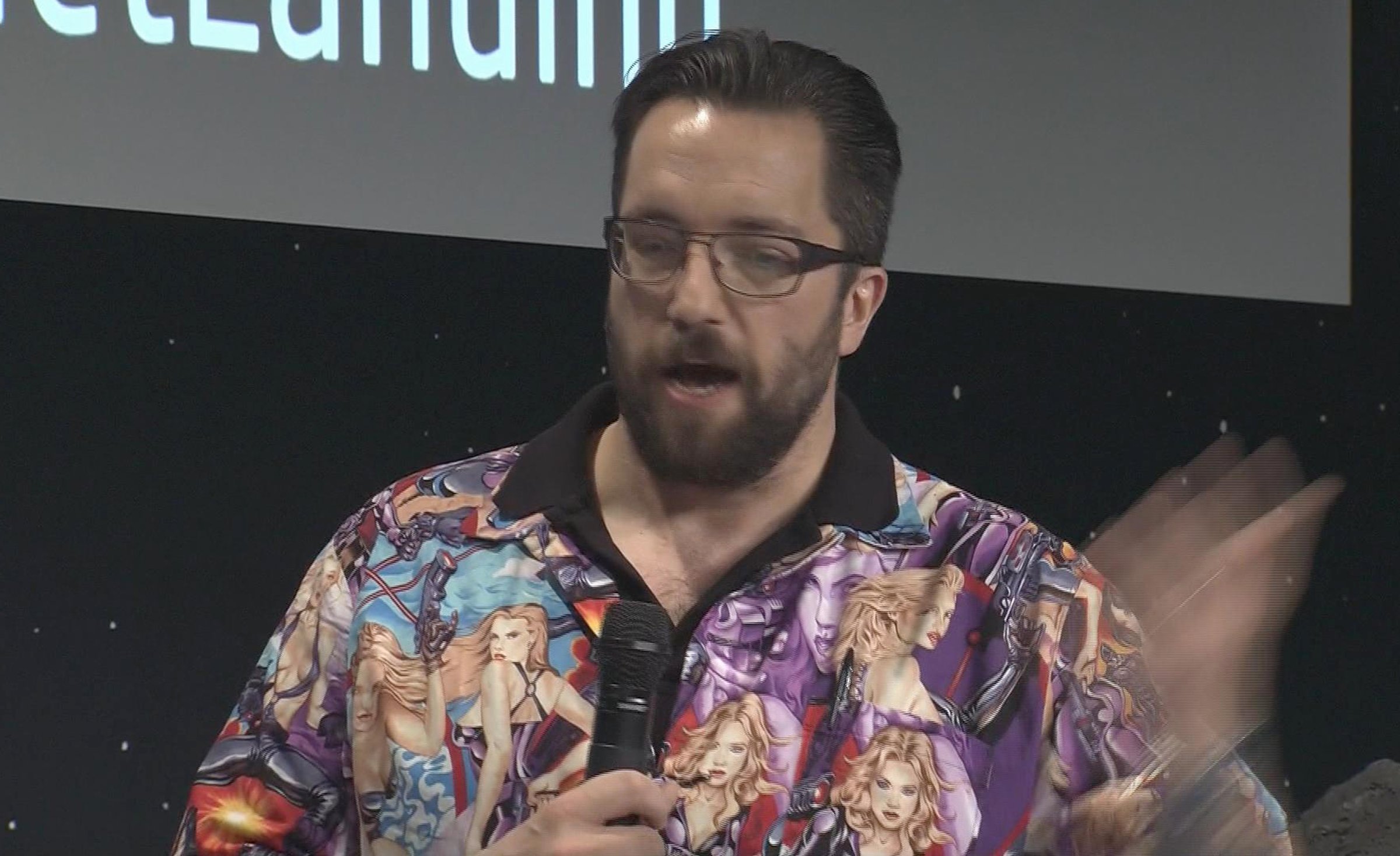

When I first heard about the outrage over a scientist from the Rosetta mission, which landed the Philae space probe on a comet, wearing a “sexist” shirt for a press appearance, I racked my brain wondering what the offensive garment could have been. A T-shirt showing a spacecraft with a “My secret fort—no girls allowed” sign? An image of a female scientist with the text, “It’s nice that you got a Ph.D., now make me a sandwich”? No, a colorful Hawaiian shirt on which, if you really looked—one censorious article actually included a description “in case you can’t see the shirt properly”—you could see cartoon images of scantily clad babes with guns. This brought on a tweet from Atlantic journalist Rose Eveleth, “Thanks for ruining the cool comet landing for me a–hole,” and a headline in the online magazine Verge that verged on self-parody: “I don’t care if you landed a spacecraft on a comet, your shirt is sexist and ostracizing.” The ShirtStorm, as it was dubbed on social media, culminated with the transgressor, British physicist Matt Taylor, offering a tearful apology for his “mistake” at a briefing.

Taylor’s shirt may not have been in great taste. But the outcry against it is the latest, most blatant example of feminism turning into its own caricature: a Sisterhood of the Perpetually Aggrieved, far more interested in shaming and bashing men for petty offenses than in celebrating female achievement.

Of course, to the feminists of ShirtStorm, the offense was anything but petty: in their view, a man who treats sexualized images of women as a source of pleasure or fun is thereby reducing women—all women—to live sex toys. Or, as one of Taylor’s critics tweeted, “His shirt says to women in STEM: I have no respect for you as a professional. When I look at you, I see a sex object.”

But that’s dubious logic. If a scientist gives an interview in a custom-made T-shirt with a photo of his wife and kids, is he telling women their sole purpose in life is babymaking? To suggest that a heterosexual man is incapable of seeing women both as sexual beings and as people is insulting to men and rather sad for women—a feminist version, if you will, of the old Madonna/whore complex (call it the bimbo/brain complex). Besides, generally speaking, cultures that censor sexualized expression have not been particularly progressive about women’s rights.

Yet this particular brand of feminist ideology, which inevitably stigmatizes straight male sexuality, is at the center of the recent culture wars. The mildest sexual innuendo and humor, even if it does not refer to women in any way, can be seen as demeaning. Last year the Internet was in an uproar after a female computer specialist tweeted a photo of two men at a tech conference to chastise them for exchanging jokes about suggestive-sounding technical terms such as forking and dongle. A leading feminist blog, Jezebel, quickly branded the jokesters—one of whom lost his job for this offense—“sexist dudes.” The Jezebel author, Lindy West, actually admitted that she had repeatedly made similar jokes herself—but insisted that in the context of a male-dominated industry, such humor excludes women.

But first of all, the exclusion is very much in the eye of the beholder. Some women are perfectly comfortable joining in ribald merriment; some men are not. Second, such arguments can too easily justify double standards that allow or even celebrate female sexual self-expression while censoring if not demonizing the male kind (which separates neofeminist prudery from its Victorian counterpart). Robin Thicke’s song “Blurred Lines,” in which a man seductively croons “I know you want it” to a woman, has been condemned as a “rape anthem” and banned from university campuses. Yet Beyoncé’s “Drunk in Love” and Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda,” songs that glamorize alcohol- and drug-fueled sex—routinely equated with sexual assault in today’s feminist rhetoric—were hailed as female-empowerment anthems in the coverage of this year’s Video Music Awards.

Such double standards exist in many environments. At a skeptic convention last year, feminist science blogger Rebecca Watson, a strong critic of sexism in the atheist/skeptic community—mostly in the form of men “sexualizing” women—gave a presentation consisting of a raunchy humorous tale in which a male ex-Mormon was ridiculed for not drinking before a casual hookup and for being overcautious about birth control. If a male speaker had dared to entertain an audience these days with similar crude humor at a woman’s expense, he would have been tarred and feathered for creating an unwelcoming environment for female attendees.

Would a female scientist have been trashed for wearing a shirt that “objectified” men or even made a male-bashing joke? Very doubtful. And if she had, most of the people outraged by Taylor’s shirt would have likely risen to her defense.

Meanwhile, Taylor was not simply ribbed for a faux pas but also targeted with nasty, sometimes violent name-calling and denounced for misogyny. Never mind that anyone who bothered to check his Twitter feed would have found out that the day before his fateful appearance in the “misogynist” shirt, he was urging his followers to follow NASA’s Rosetta project scientist Claudia Alexander. They would have also learned that the shirt was made and given to Taylor as a birthday present by a female friend, Elly Prizeman. And they would have seen a photo of him wearing that shirt right next to a smiling, waving female colleague, planetary scientist Monica Grady.

In a supremely ironic coincidence, a clip of Grady jumping in noisy joy at the Philae landing was offered by Guardian writer Alice Bell as a “positive” conclusion to a column that lambasted Taylor for his shirt and his colleagues for overlooking such a sexist atrocity.

Grady’s delight at the success of the mission clearly wasn’t ruined by a gaudy shirt with “sexualized” women on it. Sadly, the same cannot be said for Taylor: His Twitter account, so full of excitement a few days ago, went entirely silent after his public humiliation.

Sadly, the brouhaha over Taylor’s shirt overshadowed not only his accomplishments but also those of his female teammates, including one of the project’s lead researchers, Kathrin Allweg of the University of Bern in Switzerland. More spotlight on Allweg, Grady, Alexander and the other remarkable women of the Rosetta project would have been a true inspiration to girls thinking of a career in science. The message of ShirtStorm, meanwhile, is that aspiring female scientists can be undone by some sexy pictures on a shirt—and that women’s presence in science requires men to walk on eggshells, curb any goofy humor that may offend the sensitive and be cowed into repentance for any misstep.

Thanks for ruining a cool feminist moment for us, bullies.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the format of Rebecca Watson’s presentation. It was part of an entertainment program.

Read next: Cracking the Girl Code: How to End the Tech Gender Gap

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com