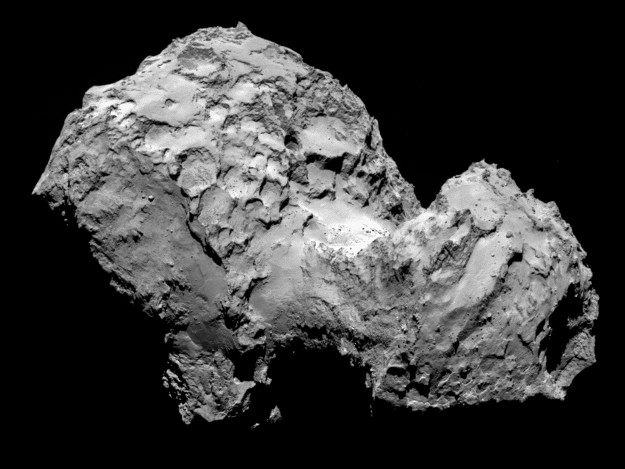

You’ve surely heard the exciting news that the European Space Agency successfully landed a small spacecraft on the surface of Comet 67P—or perhaps we should say “Comet 67P.” Because what you probably haven’t heard is that the ostensible comet is actually a spacecraft, that it has a transmitting tower and other artificial structures on its surface, and that the mission was actually launched to respond to a radio greeting from aliens that NASA received 20 years ago.

Really, you can read it here in UFO Sightings Daily, and even watch a video that seals the deal if you have any doubt.

None of this should come as a surprise to you if you’ve been following the news. Area 51, for example? Crawling with extraterrestrials. The Apollo moon landings? Faked—because it makes so much more sense that aliens would travel millions of light years to visit New Mexico than that humans could go a couple hundred thousand miles to visit the moon. As for climate change, vaccines and the JFK assassination? Hoax, autism and grassy knoll—in that order.

Conspiracy theories are nothing new. If the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the myriad libels hurled at myriad out-groups over the long course of history indicate anything, it’s that nonsense knows no era. The 21st century alone has seen the rise—but, alas, not the final fall—of the birthers and the truthers and pop-up groups that seize on any emerging disease (Bird flu! SARS! Ebola!) as an agent of destruction being sneaked across the border from, of course, Mexico, because… um, immigration.

The problem with conspiracy theories is not just that they’re often racist, foster cynicism and erode the collective intellect of any culture. It’s also that they can have real-world consequences. If you believe the fiction about vaccines causing autism, you will be less inclined to vaccinate your kids—exposing them and the community at large to disease. If you believe climate change is a hoax, you just might become the new chairman of the Senate’s Environment and Public Works Committee, as James Inhofe, Republican of Oklahoma soon will be, thanks to the GOP’s big wins on Nov. 4.

That’s the same James Inhofe who once said, “It’s also important to question whether global warming is even a problem for human existence… In fact, it appears that just the opposite is true: that increases in global temperatures may have a beneficial effect on how we live our lives.” It’s the same James Inhofe too who wrote the 2012 book, The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future. So, not good.

Clinical studies of conspiracy theory psychology have proliferated along with the theories themselves, and the top-line conclusions the investigators have reached make intuitive sense: People who feel powerless are more inclined to believe in malevolent institutions manipulating the truth than people who feel more of what psychologists call “agency,” or a sense of control over their own affairs.

That’s why the CIA, the media, the government and the vaguely defined “elite” are so often pointed to as the source of all problems. That’s why the lone gunman is a far less satisfying explanation for a killing than a vast web of plotters weaving a vast web of lies. (The powerlessness explanation admittedly does not account for an Inhofe—though in his case, Oklahoma’s huge fossil fuel industry may be all the explanation you need.)

Psychologist Viren Swami of the University of Westminster in London is increasingly seen as the leader of the conspiracy psychology field, and he’s been at it for a while. As long ago as 2009, he published a study looking at the belief system of the self-styled truthers—the people who claim that the 9/11 attacks were carried out by the U.S. government as a casus belli for global war.

He found that people who subscribed to that idea also tested high for political cynicism, defiance of authority and agreeableness (one of the Big Five personality traits, which also include extraversion, openness, conscientiousness and neuroticism). Agreeableness sounds, well, pleasantly agreeable, but it can also be just a short hop to gullible.

In 2012, Swami conducted another study among Malaysians who believe in a popular national conspiracy theory about Jewish plans for world domination. Swami found that Malaysians conspiracists were likelier to hold anti-Israeli attitudes—which is no surprise—and to have racists feelings toward the Chinese, which is a little less expected, except that if there were ever a large, growing power around which to build conspiracy theories, it’s China, especially in the corner of the world in which Malaysia finds itself.

The antisemitic Malaysians also tended to score higher on measures of right-wing authoritarianism and social domination—which is a feature of almost all persecution of out-groups. More important—as other studies have shown—they were likelier to believe in conspiracy theories in general, meaning that the cause-effect sequence here may be a particular temperament looking for any appealing conspiracy, as opposed to a particular conspiracy appealing to any old temperament. People who purchased Jewish domination also liked climate change hoaxes.

Finally, as with so many things, the Internet has been both potentiator and vector for conspiracy fictions. Time was, you needed a misinformed town crier or a person-to-person whispering campaign to get a good rumor started. Now the fabrications spread instantly, and your search engine lets you set your filter for your conspiracy of choice.

None of this excuses willful numbskullery. And none of it excuses our indulgence in the sugar buzz of a sensational fib over the extra few minutes it would take find out the truth. If you don’t have those minutes, that’s why they invented Snopes.com. And if you don’t have time even for that? Well, maybe that should tell you something.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com