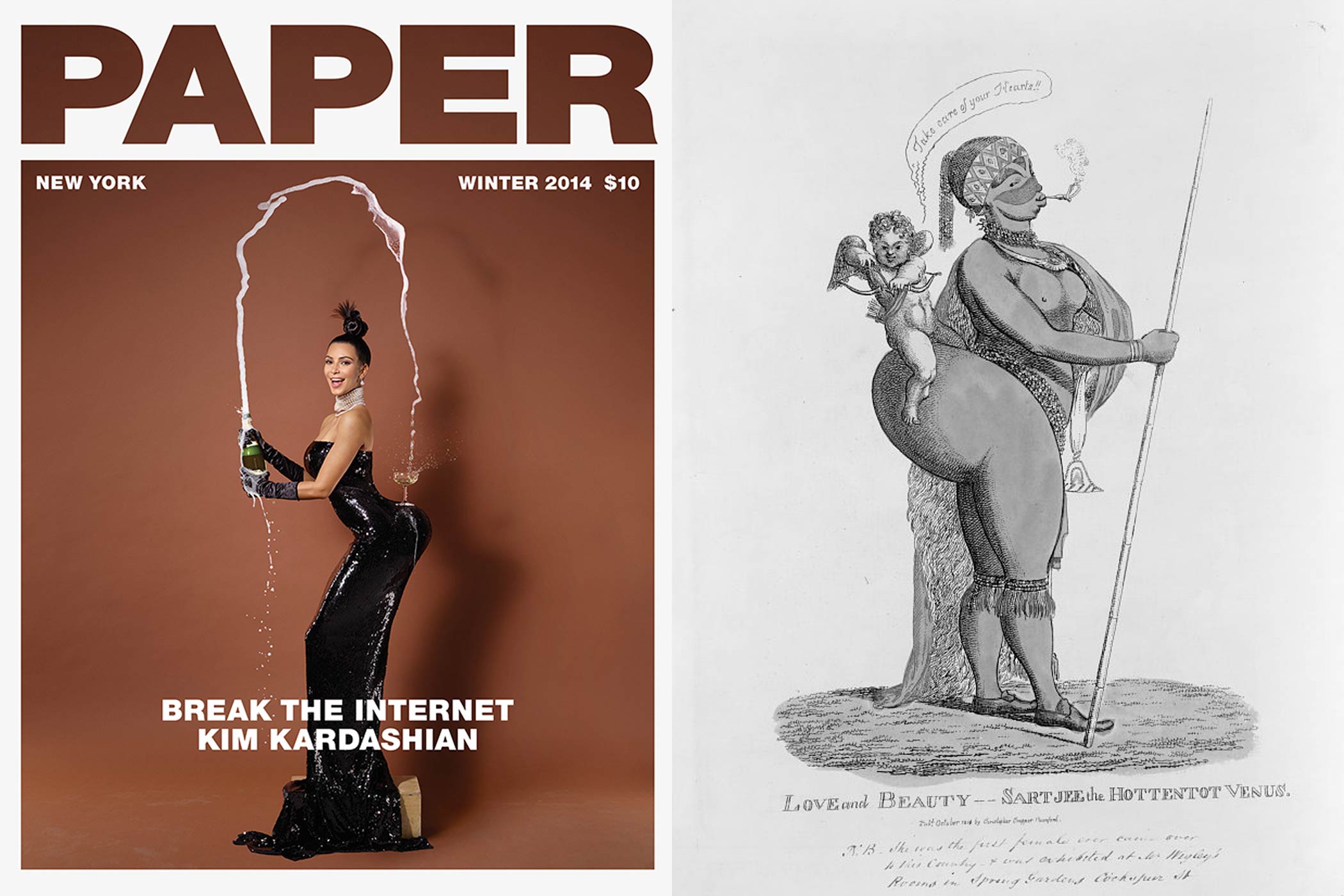

Saartjie Baartman’s is the body that launched a thousand revolutions. Kim Kardashian’s is the one that tried to break the Internet—and this week, when a nude photo of the latter made the cover of Paper magazine, many commenters made note of the striking similarities between Kardashian West’s nude profile and that of Baartman’s several centuries ago. In the 19th century, Saartjie Baartman’s striking proportions took her from Africa to Europe, where she performed as a curiosity. Her legacy in feminist circles is well known; she’s a worldwide symbol of racism, colonization and the objectification of the black female body. However, while many historians have pieced together what they believe to be the life and times of the “Hottentot Venus” during her stint as a performer in Europe, relatively little is known about the real life circumstances of Baartman herself.

In fact, even many people who are somewhat familiar with Baartman likely only recognize the 1810 illustration of the profile of her semi-nude body that once served as an advertisement for her performances in Europe. But seeing those advertisements as part of a whole life lends another dimension to her story—and to Kardashian West’s.

As researcher Bertha M. Spies detailed this summer in a piece about Baartman’s life that appeared in the journal African Arts, Baartman was born in the 1770s, about 50 miles north of the Gamtoos Valley in the Eastern Cape of what is now South Africa. She became a domestic worker, a slave employed by a Dutch farmer, before being sold to a wealthy German merchant in Cape Town. Baartman worked for the merchant until his death in 1799, at which point she moved to the home of the Cesar family, who were registered in the census as free blacks. She would give birth to three children during this time, all of whom died in infancy.

Baartman was nearly 30 years old by the time she left for Europe in 1810 with a British Army surgeon named Alexander Dunlop. As described by a 2010 biography of Baartman by Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully, Dunlop saw the attention that Baartman’s body attracted, so he worked with the Cesars to bring her to London. There, Baartman’s nude body was exhibited to the public, and she sometimes played instruments and performed dances native to the Khoikhoi tribe of her origin. Baartman would be made available for private showings in the homes of the wealthy where at extra cost, patrons would be allowed to touch her.

Baartman only ever granted one recorded interview, in October of 1810, which is now available only as a paraphrased Dutch translation. The interview was recorded in response to abolitionist’s claims that Baartman was being exploited and enslaved. In the interview, taken to England’s highest court, Baartman stated that she was happy, came to England of her own free will and was being paid for her work.

Due the constraints of language and the lack of other personal accounts, little is known about the reality of that happiness. Was she exercising her own free will in choosing what to say? Was she coerced into lying to the court? In either case, Baartman’s life and interview bring up a greater issue: is it possible to separate a person’s choices from the world in which they live? Baartman said she was showing off her body by choice, but what other choices did she have? Kardashian West is a powerful modern woman who presumably could have said no to the photo shoot, but she still lives in a culture that objectifies female bodies; how much free will can she really have? Are Baartman, Kardashian West and the bodies between doing the acting, or being acted upon?

Eventually, when his English audiences raised objections, Dunlop changed aspects of the show to make it more respectable. Namely, Baartman’s body stocking, which gave the appearance of nudity, was scrapped and she wore a tribal costume instead. But the change backfired for Dunlop: public interest waned and viewers complained. It turned out they hadn’t wanted respectability at all. The interest, unsurprisingly, had been prurient, rather than anthropological, all along.

So Baartman’s show moved to Paris, where she was on display for ten hours a day, and illness and alcohol abuse made it difficult for her to perform. During this time, interest in Baartman’s body shifted from the spectacle to the scientific; scientists used her large buttocks and extended labia to compare Blacks to orangutans. Baartman died in poverty in 1810, and her body became the property of scientist Georges Cuvier. It was displayed in a Paris museum until 1974, when activists successfully petitioned to have Baartman’s remains returned to her birthplace in South Africa.

There’s something to be said about confronting the respectability politics that deny women the agency to choose how and when they will display their bodies and the social policing that says modesty is best, but the story and legacy of Saartjie Baartman complicate these issues in ways few are able to reconcile. Unlike Baartman, Kardashian West has been able to capitalize on the public’s fascination with her body and likeness both financially and socially—but when we consider that that fascination is rooted in the same (perhaps perverse) curiosity that turned Baartman from a human being into a museum display, it is not unfair to wonder just who is exploiting whom.

Read next: I Can’t Help But Admire Kim Kardashian’s Devotion to Staying Famous

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com