Gay men are prohibited from donating blood and tissue, regardless of their HIV status, if they’ve had sex with a man since 1977. And though technology and society have radically changed since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) implemented the ban in 1983, the measure—which still bans donation by gay men, bisexual men and men who have sex with men (MSM)—has not.

It began as a measure to prevent the spread of HIV through blood donations, back when there was no simple way to detect HIV in blood. Today, testing is simple, fast and effective.

Several prominent medical groups like the American Medical Association, America’s Blood Centers and the Red Cross have opposed the ban, calling it scientifically unsound and discriminatory. In 2013, 86 members of Congress wrote to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) admonishing their delay in addressing what they believed to be an unnecessary ban.

Since 2010, the FDA and HHS have considered revising the ban, and on Nov. 13, they finally moved forward with an advisory panel voting 16-2 to adopt a one year deferral which would allow men who have had sex with other men to give blood after remaining abstinent—not HIV negative—for one year.

Advocates are calling the solution flimsy and unrealistic, telling TIME it’s one step forward and two steps back.

“It doesn’t matter whether we go from a lifetime ban or a one- or five-year deferral, because I’m in a same sex marriage and, happily, having sex more than just once a year. I am still banned from donating, so in effect, it really doesn’t change anything,” says Jason Cianciotto, Director of Public Policy at Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC). “I’ve been in a monogamous relationship for 11 years, married for 7 years, and I am not eligible to donate blood, but a person who identifies as heterosexual and admits to having sex with someone who is HIV positive is only deferred for 12 months.”

Proponents for a more lenient ruling say that even despite the high number of sexually active gay men who will still be banned from donating, the current standards also provide a false sense of security. The ban places risk on individual identities and not on behavior, meaning a sexually active gay men who practices safe sex and is HIV negative is still deemed ineligible.

Other countries have had success in changing their policies to behavior-based deferral, prioritizing a person’s actual risky sexual practices above their sexual orientation. Italy, for example, bans donations from anyone who has recently had unsafe sex. They allow donations from gays and bisexuals who have had their blood tested and sexual activity deemed safe. The country has provided data showing MSM HIV-positive individuals do not outnumber HIV-positive individuals of other groups.

MORE: This National Blood Drive Is Fighting the FDA Ban on Gay Donors

A recent analysis from The Williams Institute estimates that if the ban were to be lifted, an additional 130,150 men would likely be able to donate 219,200 additional pints of blood each year. However, an August article published in the New York Times reports that the blood industry is shrinking due to the fact that blood transfusions are on the decline. Medical innovation has eased the need for transfusions, and therefore donations, the New York Times says.

“Changing the ban has never been a top priority for the FDA, and so I do not see this as an obstacle in allowing eligible gay/bisexual men to donate blood,” says Ryan James Yezak, founder of National Gay Blood Drive. “Part of our push for policy reform is to make the blood supply safer overall—regardless of the donor’s sexual orientation or the amount of blood that is needed at any given time.”

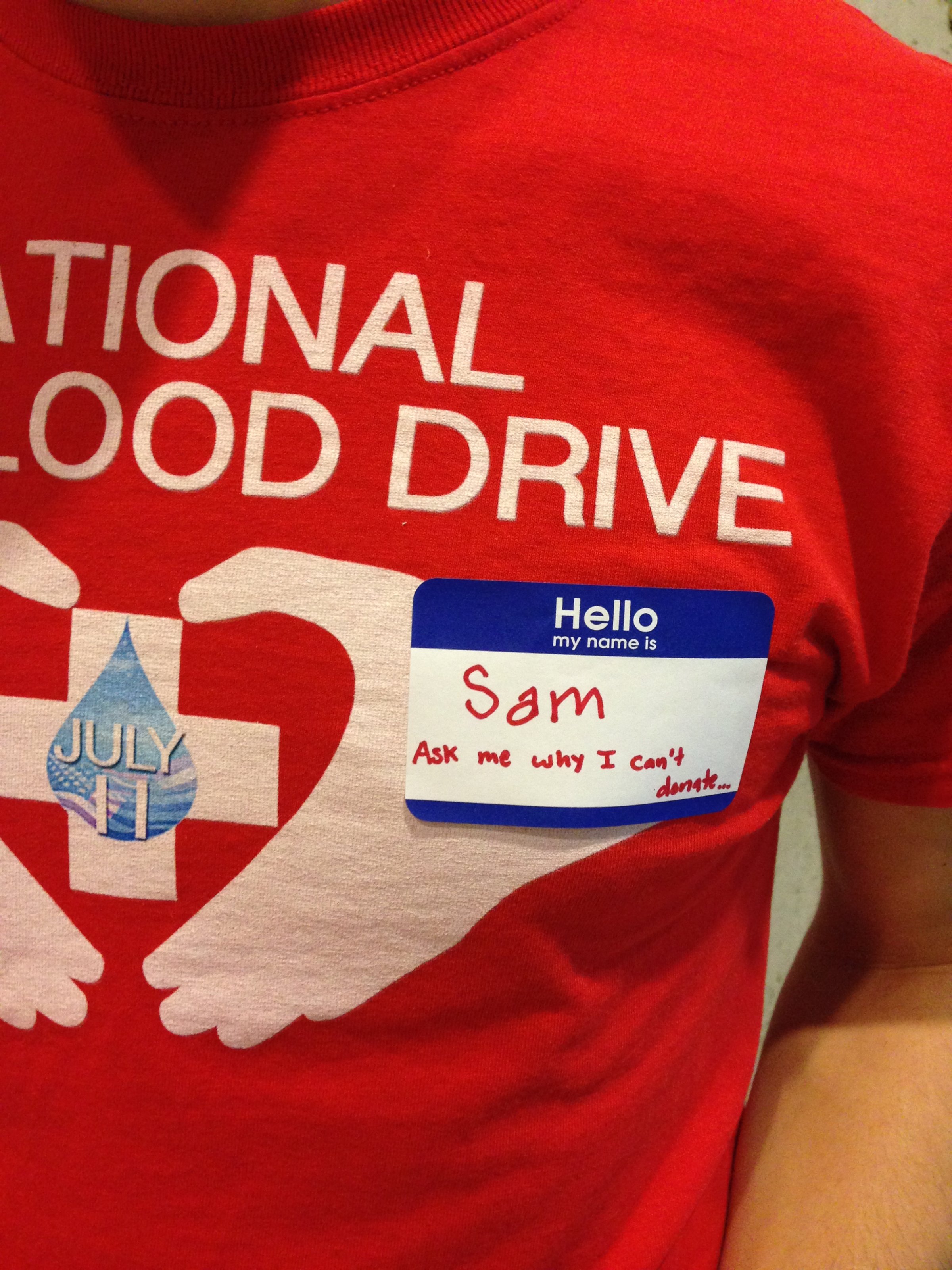

In July, the National Gay Blood Drive held its second annual drive in more than 60 U.S. cities to bring attention to the ban. The drive asks gay and bisexual men to show their willingness to donate blood by bringing eligible “allies”—friends or family members—to donate in their place. In the New York City drive, a total of 3,000 individuals participated in the event, saving up to 4,500 lives. The group also collected 44,326 signatures for a White House petition urging the FDA to change the ban.

Yezak calls the latest development a step in the right direction, though it doesn’t eliminate sexual orientation from the process. But to others like GMHC’s Jason Cianciotto, a one-year deferral ultimately doesn’t even budge the issue forward.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com