Rumors had already spread that Jim Jones’ socialist community in the Guyana jungle was no utopia. There were reports that followers had been strong-armed into staying put — some of them forced to sign false confessions that they had molested their own children, so that they would lose their kids if they left the colony. Others were beaten for infractions such as not paying sufficient attention to Jones’ sermons.

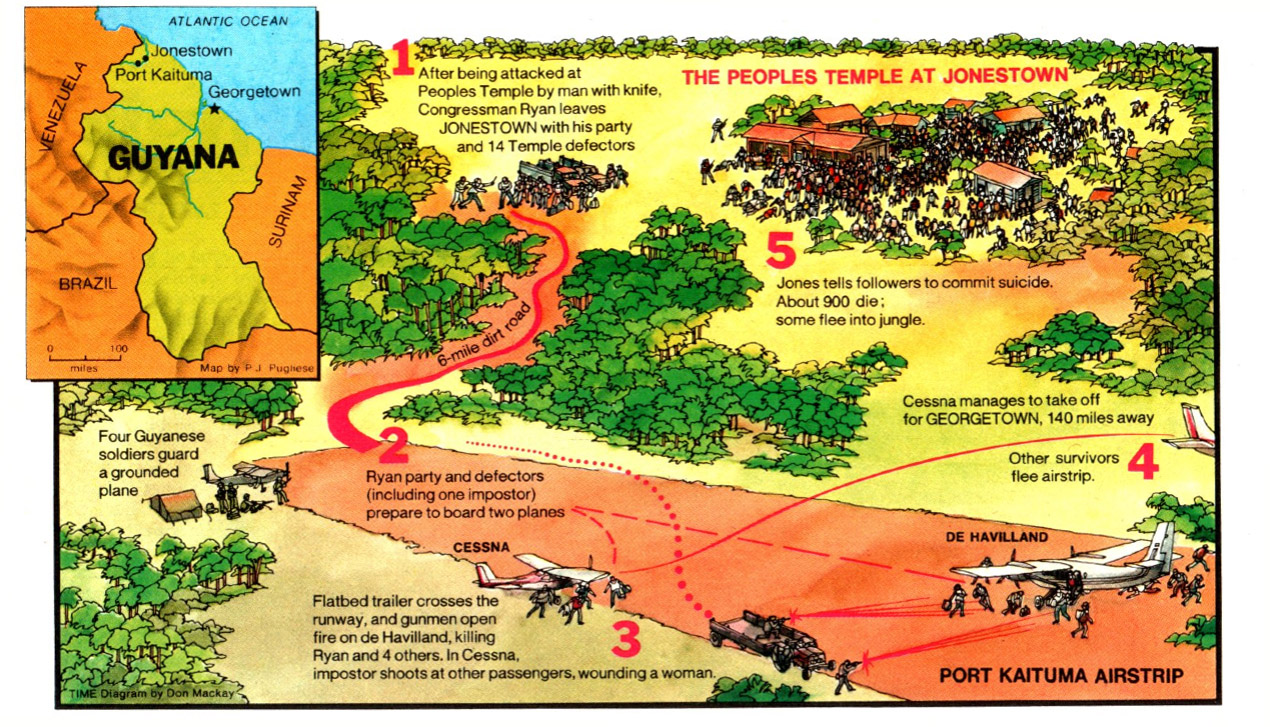

But it was on this day, Nov. 18, in 1978, that Jones earned his reputation as a tyrannical cult leader responsible for the deaths of more than 900 people — beginning with the murders of a California Congressman and several journalists who had come to Jonestown to investigate reports of abuse, and ending with the deaths of his own followers, whom he instructed to drink purple Flavor Aid laced with cyanide. As the map from TIME’s 1978 report on the massacre (above) made clear, few escaped.

How had he come so far from seemingly noble intentions? His followers had initially been attracted by his humanitarianism, beginning in the Civil Rights era, when, according to The Atlantic, he helped integrate churches, hospitals, restaurants and theaters. His vision for Jonestown — where nearly 1,000 white, black, and Latino members of his religious movement had relocated from California — was one of racial harmony and equality rooted in communism, according to a former follower, Teri Buford O’Shea, who escaped just weeks before the mass murders and suicides.

“As O’Shea tells it, Jones’ idealism was a large part of what made him so lethal,” The Atlantic explains. “He tapped into the zeitgeist of the late 1960s and 1970s, feeding on people’s fears and promising to create a ‘rainbow family’ where everyone would truly be equal.”

But there was something off about Jones even in his early days, according to Tim Reiterman, one of the journalists who was nearly killed in Guyana on this day 36 years ago. In a 2008 interview with TIME, Reiterman said he believed good and evil had always coexisted in the charismatic leader.

“Jones sought out acceptance and a sense of family through churches, but at the same time he had a tremendous need for power and control,” Reiterman said. “He would conduct little church services [as a child] up in the loft of a barn and lock his playmates in there.”

Jones’ ability to exert control became so substantial that O’Shea recalled, “The first time I met him, I was convinced he could read minds, cast spells, do all kinds of powerful things, both good and evil. I was afraid of him and stayed afraid of him for seven years.”

The good in Jim Jones eroded with drug use at Jonestown, O’Shea told The Atlantic. Just before the massacre, he seemed unwell and deeply paranoid, Reiterman told TIME. “[I]t was very bothersome to realize that over 900 lives were in the hands of this man,” he said.

Still, many of Jones’ followers believed in his vision until the end. A note from one woman who drank the Flavor Aid was later found on his body, calling him “Dad,” as his devotees addressed him.

“I agree with your decision — I fear only that without you the world may not make it to communism,” the note reads. “Thank you for the only life I’ve known.”

Read the 1978 cover story about the Jonestown Massacre, here in the TIME Vault: Cult of Death: The Jonestown Nightmare

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com