At 42, Keri Smith still writes to a pen pal. She deeply appreciates secret passageways. And she sometimes rolls dice to determine which way she walks down the street. That won’t surprise her readers who have followed instructions from her bestselling books like Wreck This Journal — a tome that asks “users” to cover the pages in dirty fingerprints, smells and drawings made by strangers.

What they might not know is that Smith, a rosy-cheeked Canadian now ensconced in Northampton, Mass., is secretly trying to spark a political movement with her whimsy. “What I’m doing is trying to get kids to pay attention, to look at the physical world more, and to question everything,” she says, leaning across a bowl of yellow heirloom tomatoes on her kitchen table. “I am trying to get kids out of the house and away from screens. Someone is needed in this culture to speak up and say this behavior is dysfunctional.”

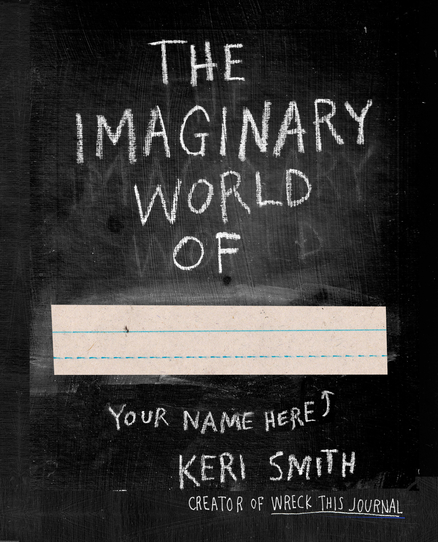

Out this fall is Smith’s 12th book (depending how you count books that often defy what a book should be), The Imaginary World Of … . Readers can complete the title with their name. Inside, they won’t find aspersions against the corporations Smith believes are “blandifying” the youth or commands to live without TV, as her family does. Instead they’ll be asked to make a list of things they’re drawn to: textures, people, sounds, colors. Then Smith will guide them through painting their own universe with that palette. Her unspoken message may be discovered along the way, if kids or adults notice their utopia didn’t include a Target parking lot or seven hours of media use per day.

In Wreck This Journal (2007), her best known work which now has more than 3 million copies in print worldwide, readers are asked to rip a page out, write a note on it and sneak it into someone’s pocket. In Guerilla Art Kit (2007), Smith presents a how-to guide on pastimes like seed-bombing, flashmobbing and situational graffiti. In How to Be An Explorer of the World (2008), she encourages readers to wander aimlessly until they have lost all sense of time and place. In Mess (2010) she instructs readers to bury the book, to do everything with the “wrong” hand for a day, and to take an existing mess and make it much, much bigger. Sometimes her fans turn those messes into more organized art.

Smith knows it’s hard to muster the kind of abandon it takes to eat colorful candy and make “tongue paintings” in one of her books, if you’re not a carefree toddler. She was once a middle-class girl in the suburbs of Toronto, where her mother suffered from a brain tumor and a rather unhappy marriage. Fights would send Smith retreating to her room to draw. By high school, Smith had turned to more destructive tools, experimenting with drugs and cutting herself in an effort to cope with home life.

Her first muse on the road to success and inhibition came in the form of a teacher who reminded her that she found solace in art. On his advice, Smith entered the Ontario College of Art and Design as a mature student a few years after dropping out of high school, a place where she was given “the permission to do whatever.” The second was her husband, an experimental musician who moved into her small farmhouse in the town of Flesherton, Ontario (pop. 700) after they wed in 2004.

Jeff Pitcher, a California native, was unprepared for the dark days that last nearly half the year, and in a moment of stir-crazed desperation, he and a friend put on headphones, walked out into the snow and started wildly dancing on the side of the road to music no one else could hear. That exercise eventually became the documentary short The Winter of the Dance, a study of “shedding predictability” and returning to a child-like state. Eventually Pitcher convinced his wife to try ecstatic heel-shaking beside a busy street. “It was life-transforming,” Smith says. “You have to force yourself into a situation that is slightly uncomfortable, because when you come out the other side it is the most freeing thing imaginable.”

From that well sprung Smith’s obsession with the precise moment a person decides to do something they are hesitant to do — like jump off a dock into numb-cold water. And her books are training manuals that make people more willing to leap. Of course, not everyone takes kindly to her exercises, which repeatedly flip the bird at convention. “In order to be who you are as a human being, you need to be willing to upset people,” she says. Smith certainly has, almost being sued after young readers followed (now defunct) instructions to “burn this page” and rub a blank page on a dirty car (which can scratch up a vehicle fast).

Despite a few detractors, Smith has a bevy of loyal followers and gets flooded with thankful letters from recovering perfectionists, school teachers and unhappy teenage girls who have been drawn to harming themselves as she once was. “I think they respond to what was my healing process, my journey out of that bad place,” she says, a combination of art and looking outward through books. Smith is a big believer in books as therapy (so long as they’re not made for that purpose), just as she is a big believer in long strolls, playing with one’s food and clandestinely chalking inspirational quotes on sidewalks instead of playing video games.

Her way of thinking may be a hard sell to children weaned on the bright, cartoony, introverted stimulation of an iPad or to parents scrambling to get their kids into computer programming classes. But she says that to fight technology doesn’t necessitate being against it forever. She knows her two young kids will have computers. “You need it to be a part of society,” she says. “I’m just hoping my children will get enough of a foundation to remember what it was like before technology, how good that feels. Because I remember.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com